Editor's note: In conjunction with our August issue on the National Park Service's centennial, we present this article by Park Service advocate Hilary Clark.

As I drove by Sunset Crater Volcano in Flagstaff, I was struck by the fiery, reddish color of the cinder cone contrasted against the snow-capped San Francisco Peaks. As I headed north on Loop Road 545 toward Wupatki National Monument, I saw the pastel colors of the Painted Desert in the distance. These were just some of the unique sites that national monuments protect. I have stood awestruck looking up at towering redwoods at Muir Woods National Monument in California, visited ghost towns, hiked desert trails, observed tide pools, and explored ancient archeological sites. Yet, with all that I have seen, I have visited less than 20 of the almost 150 national monuments across the country.

Whereas national parks require a variety of attributes — such as historic, natural and geologic — to be established, national monuments only require one. National monuments can become national parks through an act of Congress, as was the case with Grand Canyon, which was first established as a national monument in 1908. Although national parks are generally larger than national monuments, both play an important role in preserving the nation’s heritage and are deeply American. National monuments are unique, because both the president and Congress have the authority to establish them under the Antiquities Act of 1906. They can be administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, or Bureau of Land Management. In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt used the Antiquities Act to establish Devils Tower in Wyoming, which boasts unique geologic features, as the first national monument in the country. This act was established in response to the looting and vandalism of archeological sites across the country, particularly in the Southwest.

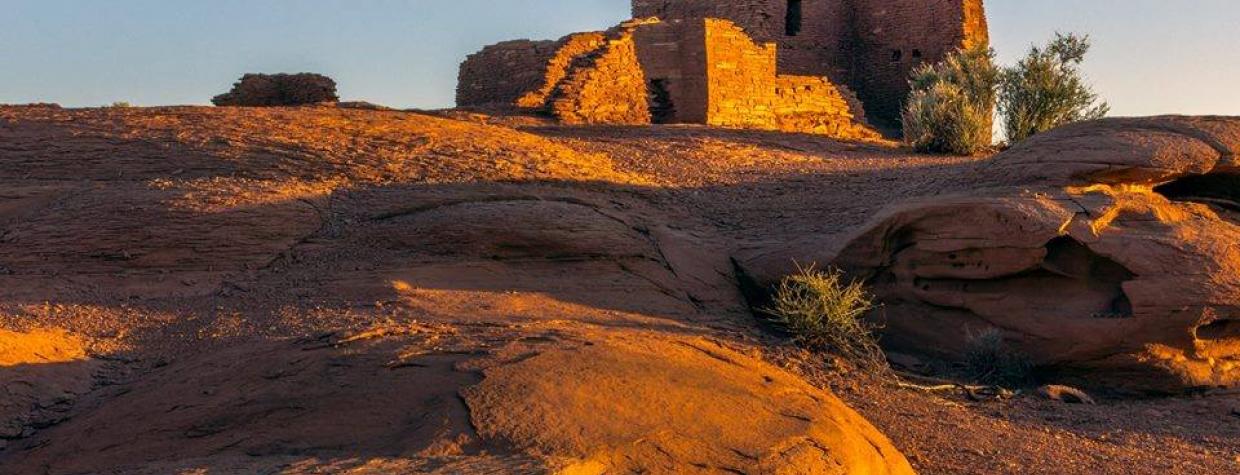

During the 1880s, the railroad brought an influx of tourists to Flagstaff, and scenic spots like Walnut Canyon became popular picnic areas. Visitors to the area would collect pottery shards and other archeological artifacts as souvenirs. In 1915, largely due to the advocacy of scientists and concerned citizens, President Woodrow Wilson established Walnut Canyon National Monument. Nine years later, in 1924, President Calvin Coolidge set aside Citadel and Wupatki pueblos as part of Wupatki National Monument. Today, more than 100 years later, visitors can hike and observe ancient cliff dwellings where Ancestral Puebloans eked out a living at Walnut Canyon, and explore different pueblos at Wupatki, which prehistorically served as a confluence of different cultural groups. As the railroad and later the automobile made travel more accessible, archaeological sites like Walnut Canyon and Wupatki became increasingly vulnerable, even to the most well-intentioned tourist. Community members are often some of the fiercest advocates for preserving these sites. This was the case with Sunset Crater Volcano, which a production company wanted to dynamite for a movie titled Avalanche in the late 1920s. Concerned community members joined forces with Harold Colton, archeologist and founder of the Museum of Northern Arizona, and successfully lobbied for the protection of Sunset Crater Volcano, which became a national monument in 1930 under President Herbert Hoover.

Many monuments have moving stories of community members lobbying for the preservation of significant ecological, historic or archaeological sites. Around the same time period that Flagstaff citizens were fighting to protect Sunset Crater Volcano, Pasadena socialite Minerva Hoyt was traveling across the country, educating people about the unique-looking yucca plants, also known as Joshua trees, in Southern California. After suddenly losing her husband and son, Minerva sought escape and solace in the desert. She camped alone under the vivid stars and found comfort in the silence of the desert. She was smitten by the desolate landscape and the unique trees, which are often compared to something out of a Dr. Seuss book. She met Teddy Roosevelt’s distant cousin, President Franklin Roosevelt, and lobbied for the protection of Joshua trees. She was successful, and in the 1930s, both Joshua Tree and Death Valley became national monuments. Today, a mural of Minerva Hoyt adorns the wall of the Joshua Tree National Park Visitor Center.

Over 60 years later, in 1994, these monuments became national parks with the passage of the California Desert Protection Act, which added more acreage to both sites and also established Mojave National Preserve. This past February, President Barack Obama added 1.8 million acres of land that serves as a buffer between Mojave National Preserve and Joshua Tree National Park, and extends to the San Bernardino National Forest. These new monuments — Castle Mountains, Mojave Trails, and Sand to Snow — provide critical habitat and wildlife corridors for animals that include bighorn sheep and mountain lions. Local citizens had lobbied for protection of these areas for several years, and it was largely due to their efforts that Obama used the authority of the Antiquities Act.

Many of the monuments we enjoy today were protected due to the foresight of those who wanted their children to experience these places as they had. In regard to preserving the Grand Canyon, Teddy Roosevelt emphasized the importance of protecting resources for the next generations. In his 1908 speech, he stated: “Let this great wonder of nature remain as it now is. You cannot improve on it. But what you can do is keep it for your children, your children’s children and all who come after you, as the one greatest sight which every American should see.”[i]

Today, millions of people visit Grand Canyon National Park and other natural wonders that have been preserved. Although many visitors are drawn to such iconic places, the variety and diversity of national monuments also has a lot to teach us about our history and the power of ordinary citizens to help protect extraordinary sites.

— Hilary Clark