Frequent Arizona Highways contributor Annette McGivney is best known for her stories on hiking and nature. But in her new book, Pure Land, she covers new, much more personal territory. In the book, McGivney delves into a murder in the Grand Canyon, the lives of the victim and the killer, and her own rediscovery of painful repressed memories of domestic violence from her childhood.

We spoke with McGivney about how the process of working on the book changed her life. (This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.)

Tell our readers a bit about yourself.

I'm the Southwest editor for Backpacker magazine; I’ve been doing that since 1996. I have basically been fortunate enough to be able to make a living out of hiking, and writing about hiking, in the Grand Canyon and other places. I’m also a professor of journalism at Northern Arizona University.

Give us some background on your latest book. How did you become involved and interested in this story?

Give us some background on your latest book. How did you become involved and interested in this story?

The book grew out of an investigative story that I did for Backpacker magazine in 2007 — it was about a murder that happened. A Japanese hiker, Tomomi Hanamure, was stabbed by an 18-year-old Havasupai Tribe member. I investigated that for Backpacker — looking into not only the murder, but also the environment down there, where there had been a lot of recent increase in crime. I was looking at it more from the perspective of Backpacker readers and what they might expect at that very popular hiking destination of Supai.

When did you realize you wanted to turn this story into a book?

The story was published in June of 2007, and I just felt like there were so many questions that I had not been able to answer in that article. I started wanting to find out more about the lives of the victim, Tomomi Hanamure, and the kid who murdered her, Randy Wescogame. I just kept persisting and finally connected with Tomomi’s family, and I went to Japan in 2009 and stayed with them for a couple of weeks. I also continued to investigate Randy’s history, of his family and the tribe.

Law enforcement said the motive for the murder of Tomomi was to rob her, and I just felt there had to be so much more to it than that, because Randy stabbed her 29 times, and that’s such a violent crime. In the Grand Canyon, that type of murder was just so unusual, and I felt there was so much more to explore beyond the simple statement that he wanted to rob her.

How did writing and doing research about Tomomi Hanamure and Randy Wescogame personally impact you?

I wasn’t completely aware of it at the time when I was first starting to explore the lives of Randy and Tomomi, but it turns out psychologically, I was really drawn to investigating the reasons behind violence because I actually grew up in a violent home and my father was abusive.

It was so psychologically terrifying when I was a child that I had sealed off memories of the worst abuse, and I wasn’t consciously aware of it. I knew my father had a bad temper, but I couldn’t remember anything. The more I got into the descriptions about Randy and how he murdered Tomomi and the reason behind it, I was actually chipping away at my own psyche and what I had been hiding from myself. The circumstances I grew up in were in some ways similar to Randy, having a violent father.

The tipping point was when I listened to Randy’s confession that law enforcement had recorded, and he described what had happened in very great detail. There was something about that that triggered my own memories so violently that I was not able to sleep, I was having nightmares and felt like I was being haunted by the murder.

I ended up going to a psychiatrist, and they were able to finally get me to admit what happened to me when I was a child. I realized I wasn’t having nightmares about what Randy did, but about what my father did. I was totally consumed with working through all the traumatic memories that were flooding back into my mind.

How long did the process of writing and researching the book take you?

It’s been 10 years from the time when I first covered the murder. I had the psychological breakdown in July of 2010, and then I kind of set things aside for a while. I put the book aside for about two years while I was working on my own mental health and getting my life recalibrated. I continued to investigate family violence and trauma, because I wanted to understand my own situation — to understand why my body was acting a certain way — and I wanted to understand how my mind could’ve possibly sealed off these memories so completely for years. I also continued to periodically read Tomomi’s travel journal.

Things had shifted so dramatically that it felt like part of the story was how the story had affected me, so I re-envisioned the book to incorporate my own experiences as well. All the while, I’ve been teaching full time and doing other freelance writing.

What was the most challenging part of the process for you?

I wanted to write the book in a way that wasn’t describing things from a distance, but kind of letting the reader know what it felt like to be Randy and to be Tomomi and to be me. Especially when I was a child. I wanted people to understand that when a kid is in an abusive home, it’s really confusing and terrifying.

In order to do that, I basically had to relive what happened when I was a child and really deeply reconnect with those memories. That was scary. I had done a lot of work to get over it and get the PTSD symptoms under control, and I was worried about having a relapse by writing about what happened. It was hard, but definitely not as bad as I was afraid it would be.

What was different about writing this book, compared with your other work?

All my previous books have always been about topics that I cared about — the environment or protecting special places that are under threat. This book was so deeply personal, and I had become so connected to Tomomi and her family. The promise I made to them, that I would write a book that would honor her, was a big responsibility that I took very seriously.

If I was going to tell my own story, I wanted to do it right, and I also wanted to do right by Randy in terms of explaining his situation. This one was much more personal and had a lot more passion behind it. From a writing standpoint, it was much more creative. It’s a narrative nonfiction book, and it was really fulfilling from a creative standpoint.

What do you hope to accomplish with your book? What do you hope readers take away from it?

I was reluctant to tell the story of my family at first, but my motivation for doing that was I’m hoping sharing my story will help other people who grew up in a home that was dysfunctional in some way. Even if it happened in the past, 20 or 30 years ago, you still carry those memories with you, and it will have an impact on you. I want to raise awareness about the impact of family violence.

I also started a nonprofit, called the Healing Lands Project, that is raising money to facilitate wilderness and river trips for children who have been removed from homes for domestic violence. I’m hoping that allowing them to be on a river trip for a week will allow them to find healing in nature, which ultimately for me was the light at the end of the tunnel — that’s how I got through as I was a kid, and that’s how I worked through my PTSD as an adult. Part of the sales of my book are going to support the Healing Lands Project. I want good to come out of telling this story.

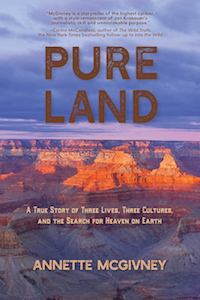

Annette McGivney’s new book, Pure Land: A True Story of Three Lives, Three Cultures, and the Search for Heaven on Earth, was released last week and is available to order on Amazon. For more about the book, visit www.purelandbook.com or www.annettemcgivney.com. You can find McGivney on Twitter @AnnetteMcGivney.

— Emily Balli