Diane Sward Rapaport isn’t unfamiliar with the publishing business. She’s published two books she’s written with her publishing company, Jerome Headlands Press. The press has produced a total of five books, all focusing on the music business, and co-published them as textbooks with Pearson Education.

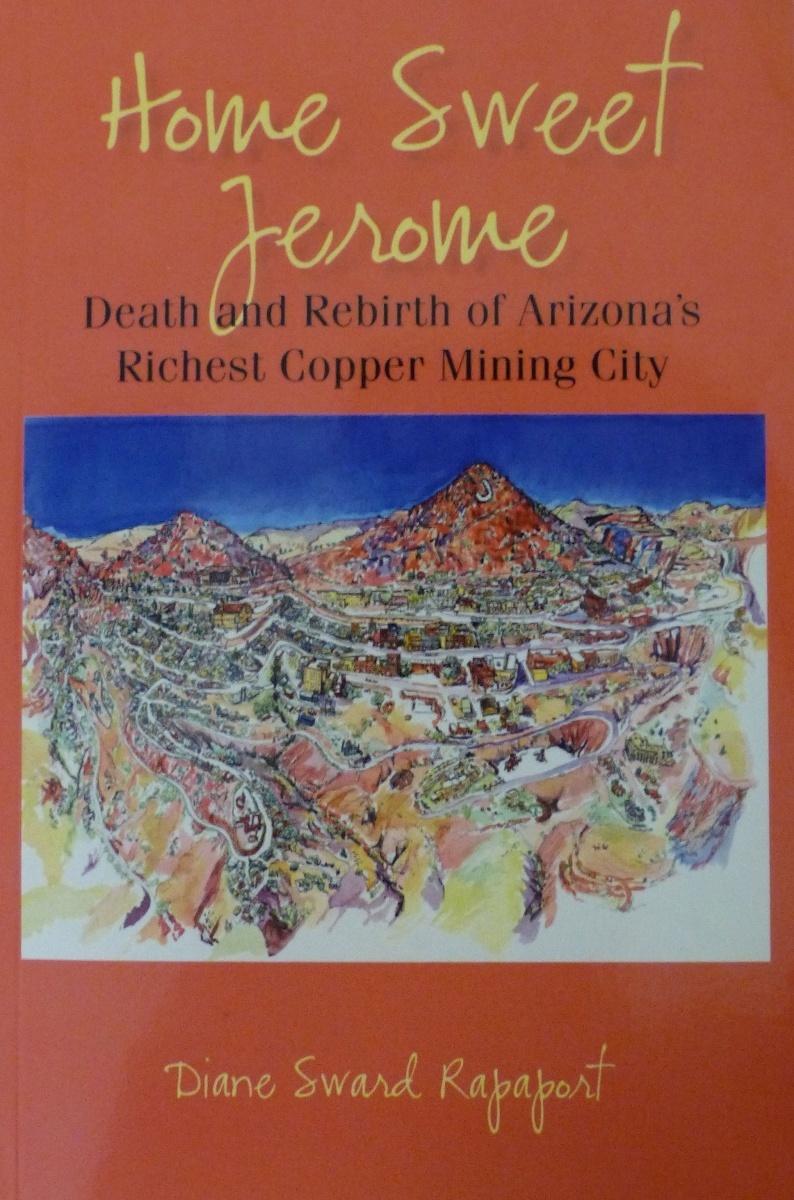

Rapaport’s newest book, Home Sweet Jerome, is a departure from her music-business history, featuring instead the transformation the town of Jerome underwent after the mining business left during the second half of the 20th century. The book compiles the stories of the people who were there to watch Jerome change and the history of those who had a hand in changing it. Arizona Highways had the opportunity to talk with Rapaport about her new book and how it came together.

Tell me about the book. What is the book about?

Tell me about the book. What is the book about?

The book is about how Jerome was rescued after the mines abandoned it in 1953, what happened when people were left stranded. You know, there were maybe 140 people and 86 kids stranded on the top of the mountain. Some had jobs, but many did not. And so how did the town come back to life? Because you see it today, and if you were here in the ‘60s or ‘70s or even ‘80s, early ‘80s when I moved in, it was a pretty derelict place. There were days when the water wasn’t happening in the early ‘80s. The sewage was on the streets. There was an area in town known as the “greenbelt” because of the sewage overflow. You look at it now, and it’s become this very pretty little restored town on the side of the mountain. So how did that happen? Who were the movers and shakers of that one?

What was your inspiration to create this book?

The stories I heard. When I first came here and started participating in politics and business in Jerome, I began to hear the stories of how people created their businesses, of what happened when they moved in, of the antipathy towards the hippies, of the stories of — just outrageous stories of theft in the church. When the old priest died. And I started putting them down without recognizing that there was a book there. I knew I always wanted to write about it, but I was so mixed up in the culture and politics that it was very hard to sort everything out and figure out what kind of perspective to come from. Of course, I was totally fascinated with the story of the snitch, the guy who betrayed the hippies and that whole ethos of growing pot, who actually helped start up the economics in Jerome. The story fascinated me.

So it was kind of the stories were the impetus for the book, but I didn’t know the context, I didn’t know how to get into a book like that, that was just focused on more than one thing. So that was how. I mean, I was so immersed in every aspect of Jerome. You live in a community of 400, you have to participate. And I did in a big way. I was president of the historical society. I was head of planning and zoning. I ran an advertising and public-relations business here. I must have written I don’t know how many resumes and press releases for people in town, as well as carrying on a fairly big publishing business. So I was involved in all the aspects and heard all the stories and knew everybody and knew all the players. So it’s hard not to think about a book.

What research did you have to do to complete the book?

First of all, I went up to the historical society and read through all the minutes and all the newsletters up into the ‘90s, every single one of them. There was a lot of meat there, and one of the things that I did not know, oddly enough, was how the society acquired property. That was a question I had: Well, how did they get all these buildings in town? How did they get to be so rich? So that was one of the questions I went into it with. Then there were missing pieces. Exactly how did the fire department get rescued, and how did the water system get fixed? There were those stories, and that I did with interviews with people that were part of the players in those stories. And then I started interviewing some of the Mexicans in the community who had moved away and found out what their childhoods were like here. So it began to have a different dimension, a deeper dimension, than just some of these disparate stories that I had been recording and writing down.

But there was actually quite a bit of research. I went through minutes, I looked at budgets. I looked at a lot of budgets from the historical society to the town of Jerome so that I would get a real handle on the economics of the town and so on.

Why should people care about your book and Jerome’s more recent history?

There’s a couple of reasons. Aside from the fact that Jerome is an iconic town and when people come here, they have all the questions about what happened, and how did the town get so fixed up, and what do people do here, and my book answers all those questions. Aside from that, I think that right now we’re in a period of great change. There are communities that are falling apart that need to understand that when communities fall apart, people need to come together from many areas of the society. Not just businesspeople, not just money people, but artists come together to help get the ideas going that will actually help rejuvenate a community. So people who are interested in community rebuilding should read this book.

I also think it has a deeper lesson. I think it cuts through a lot of clichés. Artists, for example, shouldn’t be businesspeople or politicians. Well, sorry. In Jerome, they actually became businesspeople and politicians. And so it cuts away that cliché, that artists shouldn’t participate in politics. They should just sit in their corners and make art. Well, people here don’t do that. I think that’s a lesson for other artists, so I hope that other artists will read this book, and musicians. I hope that people who are into community rebuilding will read this book. And I actually hope that people who begin to migrate—I think we’re going to be in a situation in the next 10, 20, 30 years where people are going to start to move away, say, from the coastal cities and into communities and wonder, how are they going to get into the community? How can they participate in a way that doesn’t keep them outside the community? And I think that there are lessons there too.

I guess those are my reasons why it’s a larger book. Why people should read it. Plus, it’s a real fun read on a lot of levels. Some people have told me, “Hey, this book is a riot. It’s one of the funniest books I’ve read in a long time.” Well, cool. It’s a history book. So if you enjoy reading it for its own sake like that, I guess I’ve done something. History isn't supposed to be boring.

— Molly Bilker

(Photo: Dyana Muse | Jerome)