Last April, we talked with Tucson artist David Laughlin about his life as an artist and how it's changed since his 2001 stroke. In February, a collection of Laughlin’s work featuring the Buffalo Soldiers was hung in Tucson's Quincie Douglas Library in honor of African American History Month. The collection was extended because so many people enjoyed it, and a piece from the collection may soon be featured in a permanent Buffalo Soldiers memorial at the Quincie Douglas Center in Tucson.

We spoke to Laughlin about the collection and what inspired his work.

Tell me a little about the collection of your work that is being shown in the Quincie Douglas Library. How did it all come about?

Well, it has a history. When I first heard about them doing studies on the Buffalo Soldiers, I went down there — it was still after I had my stroke — and talked to the director, who at that moment was an African-American woman.

They are considering doing a bronze sculpture memorial to the Buffalo Soldiers down there. But they’re a long way from doing a bronze sculpture, because they just don’t have the money for it — it’s a very expensive medium. My daughter has an alternative of using one of my images on a tile and enlarging it on a big tile — they sensitize the surface of the tile, print an image on it, fire it and the image is there. So that is a possibility.

There’s been a regular showing of these about every two to three years at the Quincie Douglas Library.

Have you done other work on the Buffalo Soldiers?

I have a set of my Military Hours series — it's 24 hours of a day in the life of a Buffalo Soldier, in a print medium. It doesn’t have that many guns in it; it’s all about what a cook does, how they stand guard, how they report in at different times of the year in different places in Arizona. If you have all 24 images up, you can see the kind of activities they got involved in that weren’t necessarily military.

The project with the Buffalo Soldiers started in 1981. I had six pieces made of the original group of 24, and they were finished in 1996.

I looked at the Buffalo Soldiers as peacemakers — it was not a military exercise. When they came here in 1885 and 1886 from Texas, they were only one of several cavalry and Army units on foot, and they were all just peacemakers. They kept the Indians on the reservation so they didn’t get into trouble.

What inspired you to create these pieces?

The interest was purely visual. It was something that was so impressive, and I thought that Bob Burton’s VisionQuest was doing a wonderful job with it. It was something I had heard about, but I had never seen anything where people actually did something, and Bob Burton actually took 20 or 30 kids and they marched in parades and chanted songs and verses and so on that the cavalry would’ve used. I followed them from the parade to the university. Bob Burton and the kids were my inspiration.

How long did it take you to research this project?

Well, I did the research while I was doing the project. I got to a point where [when] I finished the prints, I realized I had enough material to write a book. I made a little paperbound book from their founding; it’s all done with pen and ink, page by page. The style of it is very much 1950s comic-book style.

What medium did you use for the ones featured in the library?

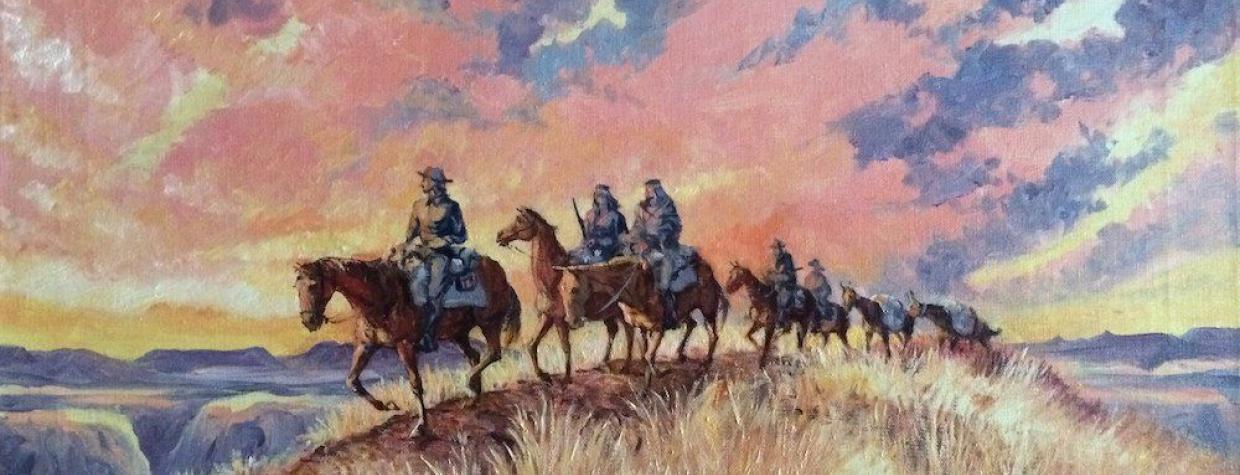

Oils, watercolors and pen and ink. There’s three different mediums, but all the same subject, close-up of Buffalo Soldiers, riding against the background. Every one of them has a story, and I could give you chapter and verse on it.

What do you hope people take away or learn from viewing this collection? What has been the response from those who have seen the collection?

It’s a curiosity — it happened a long time ago. These people didn’t have radios or cellphones, and it’s hard to imagine a home in those days that used coal oil for a lamp. It’s my most variegated work in the sense that I’m not limited to one thing. I’m a realist artist, and my work tells a story.

The work is a piece of history, and I hope that it’s relevant to people of color and people who are white who are interested in the military.

— Emily Balli

For more on David Laughlin’s work, visit www.davidlaughlinfineart.com. If you’re interested in purchasing prints of his work, you can email his daughter at [email protected].