Goodyear Builds the Tools of War

Fabricate the tools for the fighting men. Contractors working for the Navy operate plants scattered throughout the nation. If sabotage or enemy attack were to destroy any one of these plants, the loss would not cripple war time production. The navy isn't putting all its eggs in one basket. Final assembly lines could still be fed with parts from other plants, and the production line would not be stopped. Decentralization is also good insurance against local disaster such as fire or flood.

Officials of the Goodyear Aircraft Corporation and Navy officers believed there were several distinct advantages to be gained in locating the plant at Litchfield. Experience has supported their belief. Workers here enjoy better living conditions. The actual cost of living is less. In the industrial east, established plants had already employed the cream of labor available. War industry there was scraping bottom of the manpower barrel. By locating in a new territory with little industrial competition, Goodyear Aircraft has attracted an exceptionally high type of worker.

The children of victory have one religion, production to win the war; one faith, that the United Nations shall triumph; one high resolve, to give the boys on the fighting line the tools to do the job.

In the fourteen months record at Goodyear, there is irrefutable argument to contradict the timid, the defeatist, those who said we couldn't do it.

Democracy, rearming in a righteous cause, demands speed. Ground was broken at Litchfield in August, 1941. One hundred and eighty days later, the plant was in production. In one hundred eighty days, acres of concrete floor were poured. But the physical plant was only a building. W. T. Davis, Director of Personnel, recruited the human beings, the life blood of this giant, whose brain and brawn and sweat gives meaning to an inert physical mass.

Who were these people who came to work for Goodyear? They were Americans, eager for a place in their country's battle. Lawyers, salesmen, school teachers, they joined up proudly to fight for Uncle Sam in the battle for production.

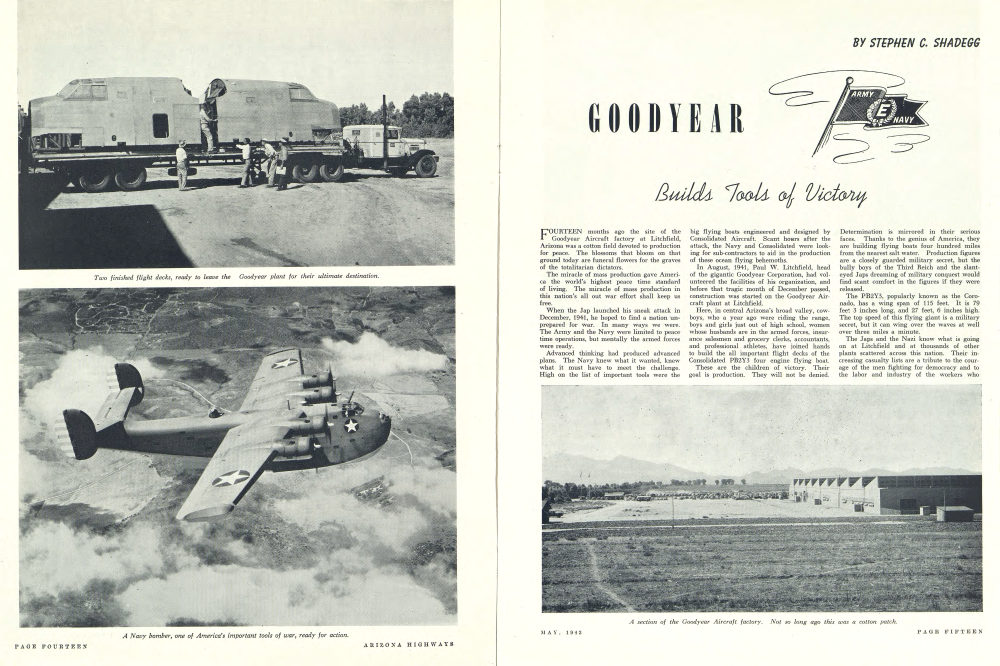

Flight decks are that portion of the flying boat fuselage above the hull where the crew functions. There are between five and six thousand parts. Each one must meet exacting tolerances. The completed flight deck must match the hulls, wings, and tail groups built in other feeder plants.

When the Naval inspectors have given their final okay, the finished flight deck is shipped away to a final assembly base to be joined to hull and wings, to be tested and checked again, and finally to meet its destiny fighting for democracy.

The children of victory know what they are fighting for. You can see it in their faces, in their preoccupation with the task before them. Every second counts, they know. Somewhere across the sea a sailor needs supplies, supplies that the Coronado can deliver. A convoy needs scout protection, protection that a Coronado can give.

Finish the job this shift. That big boat up on its final jig has a task to perform. In some lonely spot where our boys are fighting and dying, it may swing the tide of battle. These drab giants in their war paint are not mere mechanical marvels. They have enlisted in the cause of freedom.

Who are the children of victory? There is a mother whose boy died on Bataan. She knows what war means. That big Swede standing behind a turret has a son driving a tank

Speed is the essential in our American industry geared to the war tempo. Precision and teamwork on the part of man and machine secures desired results. Workers have been enlisted from countless peacetime pursuits.

for General Patton in Africa. That little dark-eyed girl in the electrical section is going to marry a boy in Australia with MacArthur, if he comes back.

They know what war means. Their sons and their sweethearts and their husbands are in the Army and the Navy and the Marines.

The complete flying boat weighs between eighty and one hundred thousand pounds. It can remain in the air for days. It can cover oceans. It is a powerful weapon designed for a specific job.

Mass production of these complicated sky giants was not to be achieved over night. The very thought of mass production of airplanes was a radical departure from previous practice.

The factory came first. There was not time to build adequate offices, so the executives of Goodyear Aircraft Corporation and the Navy personnel detailed to supervise and inspect each step in the fabrication of the flight decks moved into one corner of the factory building.

Spurred on by the terrible urgency of war, there was no time to build swanky offices for big shots. The production line was the star of the performance.

That first flight deck was practically built by hand. The assembly of that pilot model required more than the construction of the deck itself. Patterns and jigs for each part were developed as the part was made. A crude experimental production line was set up.

The important thing to remember is that the deck was finished, that it met the exacting standards of Navy inspectors. When Goodyear became a subcontractor to Consolidated the production experts on the Pacific Coast expressed the hope that the Arizona factory would be in operation in time to produce deck twenty-six. Actually, the children of victory at the Goodyear plant built deck number three.

Manufacturing methods in any aircraft plant must be flexible. Plane design is constantly changing under the impetus of battle. There was no background of experience in the mass production of aircraft on which Goodyear operations could be predicated. There was only a standard and the standard was perfection.

As the jigs and patterns gradually took form, system was born out of that confusion. Today, Goodyear's operations are being constantly improved. Sub-assemblies have reduced the time required for the fabrication of a flight deck from hours to minutes.

Actually, under the roof at Goodyear today there are thousands of little factories, each one devoted to the fabrication or the assembly of one section of the flight deck.

The method of mass production are not mysterious. Essentially they require extreme simplification.

The completed flight deck can be described as a room with windows and doors, with seats for pilot, co-pilot, chief officer, navigator, radio man and engineer. Each member of the crew must have his office or working space. In front of the pilots there are dozens of instruments and switches. Beneath the deck are hundreds of pipes and wires connected to the dials and instruments.

Anyone viewing the finished product will immediately be overpowered by the complexity. The controls, the pipes, the wiring appear to run everywhere in a mass of confusion. Can any one person understand the assembly of these thousands of parts? By comparison, a watch with its hundred or so parts, is a simple piece of machinery. Yet all of us are apt to experience a feeling of frustration when we remove the back of our watch and gaze at the wheels inside.

The proper way to approach this miracle is obviously from the other end. The Chinese proverb that a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step should guide us to a general understanding of this complicated mechanical marvel.

obviosuly from the other end. The Chinese proverb that a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step should guide us to a general understanding of this complicated mechanical marvel.

A girl fresh out of high school operates a small routing machine. She has only one job, to cut from the shiny sheets of dural and alcad aluminum the flat shapes ordered on requisition which come to her along with raw materials.

There is nothing very difficult about it. Any woman who has cut up yard goods to follow a dress pattern could understand it. The machine with its high speed cutting tool swings out over the table. On the table half a dozen sheets with the pattern on top are clamped securely in place. The router moves around and half a dozen flat shapes are ready to move on to the next little factory.

Here, and again by machine, the flat metal is given contour or shape. The operators in this little factory have only one job. Their goal is to keep the material moving along to meet the demands of the next process.

(Continued on Page Forty-two)

Already a member? Login ».