Massacre on the Gila Ushered in Peace

A FABLE ABOUT THE FINAL BATTLE LEADING TO A PEACE TREATY AMONG FIVE INDIAN TRIBES

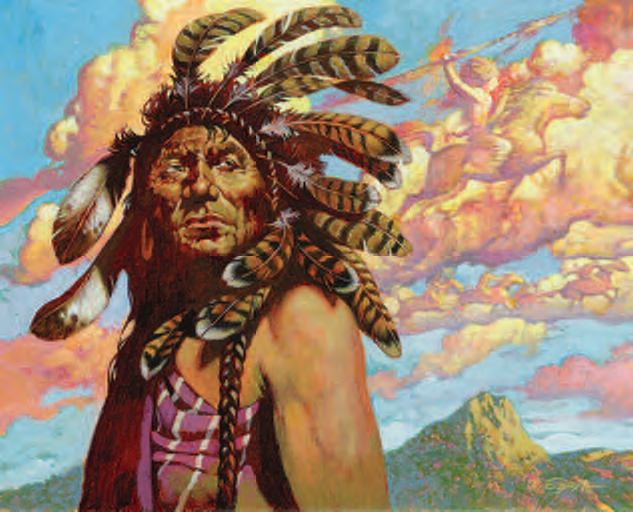

An OLD WARRIOR'S LAST HURRAH

NICKNAMED “BULL” by his fellow Bushmasters, an all-Indian combat team during World War II, Maricopa Indian elder Ralph Cameron at 88 still displayed a muscular girth of chest and neck. On April 12, 2003, I watched him dominate a podium within a makeshift auditorium at the Pee Posh Veterans Memorial Center at Laveen just south of Phoenix, between the confluence of the Salt and Gila rivers. Amid the background bustle of children playing, women cooking fry bread and barbecued beef, and teen-age girls in traditional Indian dress flirting with boys in blue jeans, Cameron recounted the reason for this gathering, the commemoration of a peace treaty signed by five Indian tribes on April 11, 1863.

One of the few remaining people who spoke the language of the Maricopa Indian tribe, or Pee Posh as they were known through the 1800s, Cameron was a living history book until his death last November.

His ancestors, he told me in an interview, kept no written records. Individuals chronicled and retold their life stories using knots and notches on “history” or “calendar sticks” that went with people to their graves. In keeping with their tribe's beliefs, their names were never mentioned again to allow them rest among their forebears. Having held their oral traditions sacred and within the tribe for centuries, some Maricopa elders, like Cameron, have decided to share the stories from their heritage with others, hoping to preserve their viability.

One such story recounts an Indian battle in 1857 at Maricopa Wells, one of 12 Indian communities stretched along 20 miles of the Gilaas it is joined by the Santa Cruz River. The two most westerly were Pee Posh settlements that had allied with the more numerous Pima Indian villages for protection against enemy tribes.

Traveling from their home on the Colorado River, the Yuma Indians, then called the Quechans, aided by some Mojaves, raided these quiet farming settlements on the morning of September 1, 1857. The battle, now known as the Massacre on the Gila, became significant as the last Arizona battle among Indian tribes. In the tradition of a Maricopa grandfather teaching morality through fables, Cameron recounted to me the following tale of that historic event. I've added names and dialogue to convey the full passion of his original story.

EAGLE'S CLAW SMILED through his dream: Legs planted like tree trunks, he drew strength from the rich earth along the east-west flowing Gila River that gave his people fish and water for their crops. He stood immovable, as unshakable as the nearby mountain the white men called Sierra Estrella. A mighty warrior from the Pee Posh tribe, he shouted insults across the line in the dirt at his enemy, the champion of the Quechan tribe. "Your great-grandfather sat backwards on his horse!"

"Your father's grandmother slept in the huts of her husband's neighbors!" "Run to Vi'Kumay, your sacred mountain - it is no more than a hill of ants."

The Quechan band quaked with fear and fury at the irreverent assaults upon the spirits of their ancestors and their sacred traditions. Eagle's Claw felt his body surge with energy from the strength of other Pee Posh warriors gathering behind him.

"I will surely win another feather for my headdress today," Eagle's Claw gloated. "These Quechans are cowardly. They will run and hide in the hills as soon as they see they can't win against the mighty Pee Posh tribe."

Thunder rumbled in the hills to the west."

The brother of your great-grandfather fought like a woman!"

Eagle's Claw laughed with scorn at this feeble retaliation from the Quechan champion. The roar of thunder from an approaching storm grew louder, and the earth reverberated, as from the pounding of horses' hooves.

IT WAS HORSES' HOOVES! "Eagle's Claw! Wake up! The horses are stampeding!" The sharpness in his wife's voice sliced through his dream. He yearned to cling to the fantasy, but Dancing Fox persisted. "Eagle's Claw, hurry!"

Instinctively Eagle's Claw grabbed for his warrior's club as he rolled from his mat.

"Ugh!" he groaned. He had forgotten about the aches and stiffness in joints and bones that had seen 76 summers.

He squinted at the dusty morning light slanting in through the east-facing doorway of the mud-caked hut.

I built this home by the ever-flowing spring when our people moved to this valley. The thought filled him with satisfaction as his eyes swept the interior.

I packed the skeleton of mesquite poles and willow branches with arrowweeds and straw that I gathered. By myself I mixed the mud and water to coat the framework to keep out the rain and the heat. Surely, I maintain it as well as any of the younger men of the village.

Despite the urgency of the moment, his eyes lingered on his headdress hanging on the wall. Its feathers spoke wordlessly of his valorous deeds, just as the singer, Cry of Wolf, sang of them in his commemorative honor songs.

What had spooked the horses this latesummer morning? The herd served as the watchdogs of the village, grazing beyond the homes along the river. When danger approached-whether wolves, mountain lions or marauding enemy warriors-the horses snorted and reared and raced through the cluster of huts with hooves drumming out alarm.

"My husband, look!" cried Dancing Fox, at last moving Eagle's Claw to action. The pungent smell of smoke carried on the dust of the disappearing herd assaulted his nostrils as Eagle's Claw crawled through the low doorway. Leaning heavily on the club in his hand, he commanded his reluctant knees to sustain his weight as he attempted to stand. Silhouetted against a western horizon dotted with flames, the figure of a runner approached. I once ran like that, when we first came to this land and found it good for farming and fishing, he thought. Like the coyote who runs for days, I ran back to tell my chief the news of this good land and its sweet water. This runner moves like Bird in Flight, the son of our son.

At that moment Dancing Fox confirmed with a shout, "It's Bird in Flight!"

Barely panting, yet glowing with perspiration on a brow too young to be furrowed with such concern, Bird in Flight grabbed his grandfather's arm and saw him wince. He loosened his grip, took a deep breath and gently pulled Eagle's Claw to his feet. "The Quechans and Mojaves marched all night and attacked the first homes in our village and set them on fire," said Bird in Flight. "Some of our women are dead. The rest have taken the children and fled to Lone Butte. You must go there, too, in In order to be safe while I gather our warriors for battle."

"What do you mean - I must go? I have never run from a battle. Look, I have my club already. I will defend our home,' answered Eagle's Claw.

"Father of my father, you were once a great warrior, but now you are an old man. You can barely walk, let alone fight." Bird in Flight pulled Eagle's Claw like a stubborn toddler toward Dancing Fox and joined their hands. Pushing the two of them in the direction of the nearby hill, he urged, "Now take Grandmother and go to a place where you can watch our battle in safety."

Bird in Flight turned to leave. "Please, Grandfather, for Grandmother's sake, go! I must warn the others," he shouted over his shoulder as he trotted away. In a moment he had broken into a gallop and was gone.

Obediently the gray-haired couple hurried toward Lone Butte.

"My headdress! He didn't let me take my headdress!" muttered Eagle's Claw.

"What are you saying?"

"If I cannot fight in the battle, at least I can let those sons of dogs know that the old man with the women and children has earned his share of feathers," he said. "I am going back for my headdress."

"Eagle's Claw, you can't! Not now! There isn't enough time! Bird in Flight said...But the aged warrior had already started back toward their hut at a pace he imagined was like his grandson's swift stride. Shaking her head, Dancing Fox walked behind her shuffling husband. "I'll wait for you here under the mesquite tree. Please hurry," she urged when they reached their starting point.

Eagle's Claw crawled into the darkness of their hut. A minute later, he emerged with the feathered band draped over his gray head like the wilted petals of yesterday's wildflowers.

"Eagle's Claw, the enemy is upon us!"

From his knees, Eagle's Claw heard his wife's panic-stricken last words, saw the arrow strike her in the back, watched her crumple like a rag doll dropped by a negligent child. Unable to catch herself, her life was gone before she hit the ground.

"No-o-o!" Eagle's Claw howled, scrambling on all fours toward his fallen mate, his companion and, as he now realized, his reason for living. The next arrow struck him in the right thigh and knocked him to his left side. He grunted and pulled himself toward her. Another arrow pierced his exposed right shoulder, nearly pinning him to the ground. Somehow he reached into his final reserve of warrior's strength and clawed his way to Dancing Fox's lifeless body. One more arrow found its mark, and Eagle's Claw collapsed alongside his wife to dream no more of wars and taunts and victories and feathers for his headdress.

In two hours it was all over. Warriors from the Pima villages had quickly joined the Pee Posh and outnumbered the attackers. Some of their enemy they trampled with their horses, some they shot with arrows, some they stoned or beat to death with heavy clubs. Two or three were allowed to escape and return to describe their defeat to the women and children and old people they left behind in their villages to the west. The bodies lay where they fell, never to be touched or moved or buried, only to cook in the hot desert sun, to decay and return to the dust of their origins, leaving bleached bones on the dry earth. As the women and children straggled back to their homes from the safety of Lone Butte, the singer Cry of Wolf strode through their midst, his head filled with songs of victory and triumph for his Pee Posh people. He stopped when he came upon the bodies of Eagle's Claw and Dancing Fox, and looked over the bloodstained field of enemy corpses. His elation evaporated like a drop of rain on the desert floor in the heat of summer.

With sudden insight, Cry of Wolf understood the futility of their ongoing feud with their neighbors to the west and felt pity for the disgraced Quechan tribe, which had lost nearly all of its warriors. The spirit of a song came upon him and he sang: "I'mahn'o mahna'che no.

Right now my heart is all darkened. Later generations will sing this song Of Vi'Kumay, Mojave sacred mountain. You are like an old woman, You have painted your walking cane, And now after this battle, You are leaving your home grounds. O'yay'kah o'kay yah'ko Where can I look? Where can I look? But these things are forever turning my head, And I see, And I fear that place."

FIVE YEARS AFTER THE BATTLE, the Maricopa and Pima tribes signed a treaty with the Quechan (or Yuma), Hualapai and Chimehueve (a branch of the Mojaves) tribes ending generations of warfare. On April 11, 1940, representatives from all of the tribes attended the first Festival of Peace commemorating the signing of the treaty and honoring their ancestors, and setting aside longstanding grievances to build a future of peace. Each April the celebration continues at the Pee Posh Veterans Memo rial Center.

Eagle's Claw and Dancing Fox did not hear Cry of Wolf's honor song, and did not know of their enemies' defeat in this 1857 battle at Maricopa Wells along the Gila River. But their story and the song live on in a tenuous existence. As a young girl, Ralph Cameron's mother, May Eliff, had watched the battle from a hillside. Seventy years later, she sang the song to Cameron, and 73 years after that, Cameron sang the song to me in hopes of preserving it for future generations.

Already a member? Login ».