TO THE RESCUE

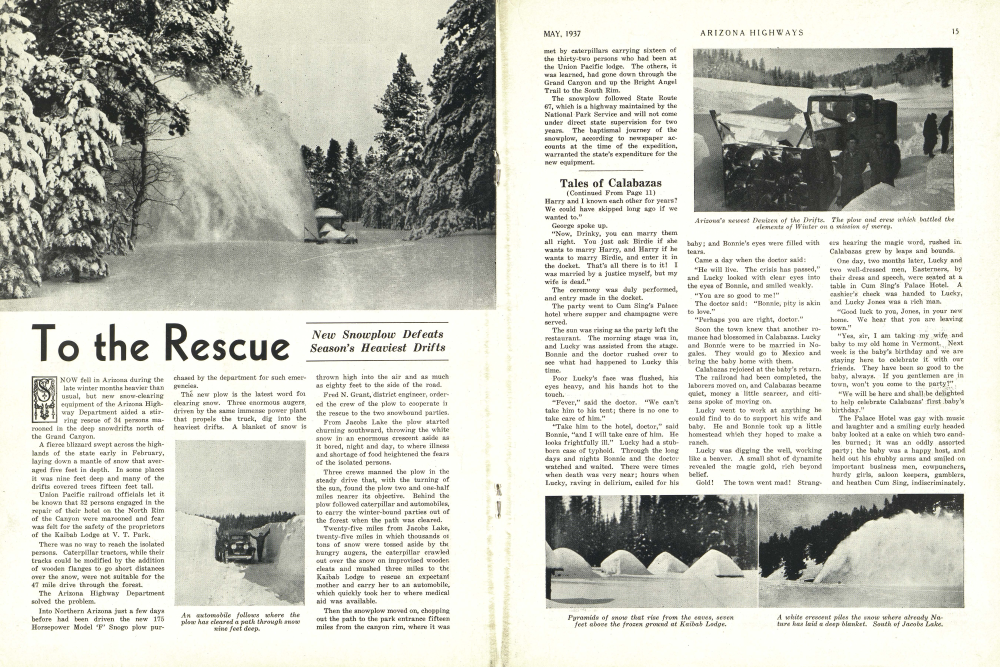

NOW fell in Arizona during the late winter months heavier than usual, but new snow-clearing equipment of the Arizona Highway Department aided a stirring rescue of 34 persons marooned in the deep snowdrifts north of the Grand Canyon. A fierce blizzard swept across the highlands of the state early in February, laying down a mantle of snow that averaged five feet in depth. In some places it was nine feet deep and many of the drifts covered trees fifteen feet tall. Union Pacific railroad officials let it be known that 32 persons engaged in the repair of their hotel on the North Rim of the Canyon were marooned and fear was felt for the safety of the proprietors of the Kaibab Lodge at V. T. Park.

There was no way to reach the isolated persons. Caterpillar tractors, while their tracks could be modified by the addition of wooden flanges to go short distances over the snow, were not suitable for the 47 mile drive through the forest. The Arizona Highway Department solved the problem.

Into Northern Arizona just a few days before had been driven the new 175 Horsepower Model 'F' Snogo plow pur-chased by the department for such emergencies. The new plow is the latest word for clearing snow. Three enormous augers, driven by the same immense power plant that propels the truck, dig into the heaviest drifts. A blanket of snow is

New Snowplow Defeats Season's Heaviest Drifts

Thrown high into the air and as much as eighty feet to the side of the road.

Fred N. Grant, district engineer, ordered the crew of the plow to cooperate in the rescue to the two snowbound parties.

From Jacobs Lake the plow started churning southward, throwing the white snow in an enormous crescent aside as it bored, night and day, to where illness and shortage of food heightened the fears of the isolated persons.

Three crews manned the plow in the steady drive that, with the turning of the sun, found the plow two and one-half miles nearer its objective. Behind the plow followed caterpillar and automobiles, to carry the winter-bound parties out of the forest when the path was cleared.

Twenty-five miles from Jacobs Lake, twenty-five miles in which thousands 0f tons of snow were tossed aside by the hungry augers, the caterpillar crawled out over the snow on improvised wooden cleats and mushed three miles to the Kaibab Lodge to rescue an expectant mother and carry her to an automobile, which quickly took her to where medical aid was available.

Then the snowplow moved on, chopping out the path to the park entrance fifteen miles from the canyon rim, where it was met by caterpillars carrying sixteen of the thirty-two persons who had been at the Union Pacific lodge. The others, it was learned, had gone down through the Grand Canyon and up the Bright Angel Trail to the South Rim.

MAY, 1937

The snowplow followed State Route 67, which is a highway maintained by the National Park Service and will not come under direct state supervision for two years. The baptismal journey of the snowplow, according to newspaper accounts at the time of the expedition, warranted the state's expenditure for the new equipment.

Tales of Calabazas

(Continued From Page 11) Harry and I known each other for years? We could have skipped long ago if we wanted to.

George spoke up.

"Now, Drinky, you can marry them all right. You just ask Birdie if she wants to marry Harry, and Harry if he wants to marry Birdie, and enter it in the docket. That's all there is to it! I was married by a justice myself, but my wife is dead."

The ceremony was duly performed, and entry made in the docket.

The party went to Cum Sing's Palace hotel where supper and champagne were served.

The sun was rising as the party left the restaurant. The morning stage was in, and Lucky was assisted from the stage. Bonnie and the doctor rushed over to see what had happened to Lucky this time.

Poor Lucky's face was flushed, his eyes heavy, and his hands hot to the touch.

"Fever," said the doctor. "We can't take him to his tent; there is no one to take care of him."

"Take him to the hotel, doctor," said Bonnie, "and I will take care of him. He looks frightfully ill." Lucky had a stubborn case of typhoid. Through the long days and nights Bonnie and the doctor watched and waited. There were times when death was very near; hours when Lucky, raving in delirium, called for his

ARIZONA HIGHWAYS

baby; and Bonnie's eyes were filled with tears.

Came a day when the doctor said: "He will live. The crisis has passed," and Lucky looked with clear eyes into the eyes of Bonnie, and smiled weakly.

"You are so good to me!"

The doctor said: "Bonnie, pity is akin to love."

"Perhaps you are right, doctor."

Soon the town knew that another romance had blossomed in Calabazas. Lucky and Bonnie were to be married in Nogales. They would go to Mexico and bring the baby home with them.

Calabazas rejoiced at the baby's return.

The railroad had been completed, the laborers moved on, and Calabazas became quiet, money a little scarcer, and citizens spoke of moving on.

Lucky went to work at anything he could find to do to support his wife and baby. He and Bonnie took up a little homestead which they hoped to make a ranch.

Lucky was digging the well, working like a beaver. A small shot of dynamite revealed the magic gold, rich beyond belief.

Gold! The town went mad! Strangers hearing the magic word, rushed in. Calabazas grew by leaps and bounds.

One day, two months later, Lucky and two well-dressed men, Easterners, by their dress and speech, were seated at a table in Cum Sing's Palace Hotel. A cashier's check was handed to Lucky, and Lucky Jones was a rich man.

"Good luck to you, Jones, in your new home. We hear that you are leaving town."

"Yes, sir, I am taking my wife and baby to my old home in Vermont. Next week is the baby's birthday and we are staying here to celebrate it with our friends. They have been so good to the baby, always. If you gentlemen are in town, won't you come to the party?"

"We will be here and shall be delighted to help celebrate Calabazas' first baby's birthday."

The Palace Hotel was gay with music and laughter and a smiling curly headed baby looked at a cake on which two candles burned; it was an oddly assorted party; the baby was a happy host, and held out his chubby arms and smiled on important business men, cowpunchers, hurdy girls, saloon keepers, gamblers, and heathen Cum Sing, indiscriminately.

A Monument To Early Travel

(Continued From Page 3)four going to the right, and five to the left, attempting to encircle the couple.

Kruger's accurate aim kept them at a distance, although he had nothing but a pistol, and he was wounded. Heavy arms of the party never were brought into use, as they had been stacked beneath the coach seats.

For five miles, the game of hare and hounds continued, until the two met a mail buckboard coming from town. They quickly unloaded the cargo and stacked it to form a barricade, the driver whirled the team, and headed back to Wickenburg for help. It arrived early the next day.

The two remained crouched behind the sacks for hours, awaiting the expected Indian charge, which failed to come. The Indian ammunition, apparently, was exhausted and they finally abandoned the battle, fearing to be trapped by the rescue party.

The long vigil through the night behind the mail sacks, with no medical attention, and the anxiety, proved a severe strain. Miss Sheppard was wounded in her right arm, and twice in the shoulder. She died in California some time later from the ordeal, according to a report brought back to Arizona by Kruger. She was the last of six victims.

Veteran trackers next day took up the trail left by the ambuscade party, which led directly toward the reservation of the Apache-Mohaves, on Date Creek. There was little attempt at concealment.

Evidence that these Indians were responsible included bits of paraphernalia left behind, the fact that a considerable part of a reported $12,000 in bank notes and other valuables were not taken, and the testimony of a friendly chief of a neighboring tribe.

Contradictory evidence included the fact that ammunition was not stolen, and that the stage horses were left. Additionally, there was a large sum of money supposedly carried in the shipment and by the passengers, and there was the statement of C. B. Genung, Peeples Valley settler, that a Mexican woman (Donna Tomase) advised J. M. Bryan, who held the government mail contract from Wickenburg to Ehrenberg, that the stage was unsafe, there being a plot to waylay and rob it. Her advice was said to have prevented his use of the stage thereafter for business trips.

Genung gave the names of those believed to have been the perpetrators. If they were guilty, they paid in full.

One supposedly was wounded at the scene, and after incarceration in the Phoenix jail was killed there; another died in a fight in a corral on the banks of the Agua Fria; and the "ringleader"

and a fourth were killed when they ran amuck in Phoenix. "The right men" disposed of other members, Genung related.

On the other hand, if the Mohave-Apaches were guilty, they paid the penalty.

Retribution, however, was long delayed. Not until the seventh of September, 1872, did Gen. George Crook reach the reservation on his mission of punishment. The purpose had been carefully concealed from the Indians. The dramatic denouement was to come with presentation of a piece of tobacco for identifi-cation to each of the guilty braves, by Irataba, a friendly Indian.

The Indians, ostensibly assembled for a peace conference, suspected the purpose of the tobacco gifts at the last moment. Most of them had left their weapons some distance away, however.

A sudden affray which followed soldiers' attempts to seize those identified resulted in the deaths of about a dozen braves. A number of innocent Indians undoubtedly were slain.

General Crook himself missed death very narrowly, a trooper knocking aside an Indian who had drawn a bead upon him. Some historians report that the Indians had planned from the beginning to use the assembly as occasion for murdering Crook.

No serious uprising of the Apache-Mohaves followed, largely because of the preponderant military strength in that district. They were soon returned to the reservation.

Final war on the Apache Indians of Eastern Arizona came not long afterwards. The government, pressed by criticism stirred up by the Wickenburg massacre, began a campaign of "liquidation" November 15, 1872, which continued with few interruptions until Apache power was broken forever in Arizona The Wickenburg massacre monument was built by James L. Edwards, highway maintenance foreman, and other highway workers in off-duty time. It is 11 feet wide at the base, and eight feet at the top. It stands six feet in height. and was constructed of white quartz from the Apache mine. The mounted replica is of bronze.

Edwards also recently constructed the Hi Jolly monument near Quartzite, and the monument to pioneers in the old cemetery at Ehrenberg.

A three and one-half foot copper map of Arizona on the Wickenburg monument base bears the inscription:

WICKENBURG MASSACRE

In this vicinity, Nov. 5, 1871, Wickenburg-Ehrenberg stage ambushed by Apache-Mohave Indians, John Lanz, Fred W. Loring, P. M. Hamel, W. G. Salmon, Frederick Shoholm, and C. S. Adams were murdered. Mollie Sheppard died of wounds. Arizona Highway Department, 1937.

The records of the massacre are preserved in a four-inch steel vault, embedded in the heavy rock below the copper table. On the cap of the record vault are the numerals, 1937.

A 16-foot flagpole marks the monument. Rich copper ore specimens glisten from its base.

The entertainment of nearly 5,000 visitors to the dedication was arranged by the Roundup club of Wickenburg, headed by Roy L. Richards. Barbecue and speeches were features of the program.

In addition to dedication of the monument, the program celebrated completion of the new highway underpass at Wickenburg below the Santa Fe railroad, and other highway work in the Wickenburg district.

The monument dedication marks an important step towards "dressing up" Arizona roadways, and preservation of important historical landmarks and lore. The replica seems to have caught the coach, with its two-span team and driver, in a moment of vivid action drawn from real life.

Specialists on Reinforced Steel Mesh Guard, Fence Stays 1534 Blake Street, Denver Plants at Denver and Pueblo

MAY, 1937 ARIZONA HIGHWAYS 17 In the Year 1540

(Continued From Page 6) Indies to enable him to hold back the Turks in Hungary, to defeat his French rivals in Holland, and to quiet the restless German princes who have been listening to the teachings of Martin Luther and who are soon to break with the Catholic Church in the Protestant Reformation.

Across the Mediterranean medieval Italy basks in the fading glow of the Re-naissance. In Florence the people are again supreme, the Republic is reestab-lished, the infamous Medicis have been expelled. In Rome Pope Paul III listens to the fervid appeals of Ignatius Loyola and grants his request to organize the Jesuit Society, which later figures so prominently in the Catholic counter-Re-formation, and in the spiritual conquest of the New World.

While the Christians of Europe kill each other the Mohammedans are surg-ing over the Balkan Peninsula and threat-ening the very gates of Vienna. To the east across the Plateau of Iran in teeming India, Baber, the Moslem conqueror, has been dead but ten years and the line of Great Moguls established by him is to rule that ancient country for six generations, bringing to it the most splendid age in its history.

Our glance returns to Europe. The armies of Francis I of France and Charles of Spain are at death grips. In England Henry VIII loots the vast wealth of the Catholic Church. We marvel at that tiny isle knowing that fifty years hence it will crush the mightiest fleet of the mightiest sea power in Europe, the Span-ish Armada.

Everywhere there are wars and rumor of wars. Little men march across the face of Europe and of Asia, their flags flapping in the winds, their armour flashing in the sun, killing each other in the name of God and king. It is so in 1540 even as it will be in the Twentieth century.

Across the Atlantic to the westward a fleet of galleons enters the Spanish Caribbean. To the north lies a great continent, covered with primeval forest and inhabited by savage red men. A great river flows slowly to the sea, and in the lowlands of what we now call Louisiana, a weary group of Spaniards is fighting fever and hunger. It is DeSoto and his fellow explorers, the only white men in that vast region; DeSoto, soon to discover the Father of Waters and his grave.

Across the gulf to the south and west towers a land of high plateaus and rugged mountains. Here and there in their midst are small dots of Spanish civilization. Lima, Santiago, and Mexico City already have their universities, cathedrals and hospitals. The great Inca and Aztec empires, once predominent in this region, have been crushed and forgotten. European civilization has taken hold in the New World.

We look northward toward what is now Arizona. A small band-fifty horse-men, some foot soldiers, friars, and Indians-trudges through the cactus and sand, under the glare of the summer sun. It is Coronado and his comrades, the only other white men within the present boundaries of the United States, heading toward the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola, seeking man's everlasting curse, gold. They are following the lead of Friar Marcos de Niza, who tells them of the gleaming minarets in the Golden Cities which he claims he discovered the summer before. They constitute the advance contingent of three hundred Spaniards and a thousand Indians whom Mendoza, the King's Viceroy in Mexico, started on a great expedition the preceding February.

It had been an auspicious occasion. Francisco Vazquez Coronado in glistening gilded armour, plumes fluttering, astride a prancing thoroughbred, led the gay and colorful army. At least two hundred mounted, gaily caparisoned troops, armored, and with their polished lances erect in the sun, marched behind them. One hundred foot soldiers with crossbars or arquebusses, swords and shields, followed. And behind them tramped a thousand war-painted Indians. Herds of sheep and cattle brought up the rear.

This was the brilliant and carefree host which was reviewed by Mendoza at Compostela, Mexico, February 23, 1540. It was all but one hundred of that large and slow-moving group that Coronado left behind him at Culican in May.

We can see Coronado and his little party after weary days of heat and thirst, long hours of travel in the high cold mountains of Arizona and New Mexico, gaze with disappointment and chagrin at the mud pueblo, today called Zuni, which was the actual realization of De Niza's dreams and imagination. We can watch him two years later, sad and disillusioned, returning home, as did Colum-bus forty years before, to semi-disgrace and oblivion, empty-handed and without honors.

But as we watch we know that the Finger of Time is writing indelible words about this Southwest on the pages of history and that Coronado's name will always be among them. And we know that though Coronado and De Niza are cast aside as failures by their fellow men, the people who, in the Twentieth century, are to live in this land of nature's superlatives, will honor these men whose courage and faith erased from the American Southwest the name of Terra Incognito.

Spanish Influenced Arizona's Culture

(Continued From Page 7) He became a conqueror. He passed through villages of unprotesting natives, (sedentary Indians, probably Pimas) gathering turquoise baubles for his personal adornment, the most comely girls for his harem, and the most stalwart men for his bodyguard. He sent frequent runners back to Fray Marcos to acquaint the priest with the progress; but to Fray Marcos' repeated commands to stop and wait, the slave paid no heed.

With his ever-growing band of follow-ers he crossed the Gila River, probably in the spring of 1539; leaving behind the sedentary tribes, he entered the country of the warlike Apache and Navajo. Even in this region he met no opposition; he pushed on triumphantly to the first of the Cities of Cibola, eight miles east of the present Arizona-New Mexico line.

Here he encountered unexpected opposition. The Zuni Indians who inhab-

ARIZONA HIGHWAYS MAY, 1937

ited the village were not awed by Este ven's black skin. Their women shrank from his touch. Here was a tribe pre pared to defend its own and here it is probable that Estevan met violent death.

There is a legend that Estevan, wound ed, was held as a slave in this place and that Cibola was truly a golden city. Thus Cibola has taken its place among the lost gold legends of the Southwest. However, it is more probable that the adobe village later shown by Indian guides to Fray Marcos was actually the same village Estevan had attempted to plunder, and that the Indians' report of Estevan's death was true.

Upon receiving word of the negro's fate Fray Marcos proceeded at once in Estevan's footsteps, and reached the top of the hill whence the slave had first viewed the pueblo. What Marcos looked at was an adobe village; what he saw was an illusion a golden city. Perhaps the effect of light and distance lent the village great size and color. Possibly his excited imagination endowed Cibola with all that he wanted it to be. He wished to enter the city, but his Indian guides persuaded him to turn back. Fray Marcos planted a small cross on the hill, claiming the territory for God and the King of Spain, and hurried back to the viceroy with a report of the first city "which is situated on a plain at the foot of a round hill and maketh show to be a fair city." The houses, he said, were built of stone, with many stories and flat roofs. The people seemed white, and they possessed emeralds and other jewels, but held the turquoise in highest esteem. The inhabitants, he said, used vessels of gold and silver since they had no other metal (so the Indians had told him.) Upon the priest's return to Mexico, a small army of 300 Spaniards and 800 Indians was organized to accompany Fray Marcos back to the Seven Cities. Mendoza staked his entire personal for tune, and without authority even drew upon funds to finance the expedition. Francisco Vasquez Coronado, young gov ernor of New Galicio, was chosen to lead the army. His following consisted in the main of numerous idle and useless young aristocrats of the city, whom Mendoza had invited to join the expedition mainly to rid the country of their presence.

The expedition set out February 23, 1540. Coronado, clad in golden armor, led the procession. The horses were of the proud stock from the viceroy's breed ing ranches. Their rich trappings reach ed nearly to the ground. They carried armoured soldiers, with lances erect and swords and other arms in place. Behind them marched the foot soldiers bearing crossbows, arquebuses, swords and shields. The natives were in full war regalia and carried clubs or bows. Behind were herds of cattle and sheep to assure food, and extra horses and mules loaded with camp supplies as well as a number of swivel guns.

Most of the Indians that Coronado's army encountered were awed into sub mission at the first sight of the caravan. They had never seen white or bearded men before, on horses, and they probably believed that both horses and horsemen had descended from the sky. Some of the Indians resisted, however, and small scouting parties from the expedition were ambushed. Coronado's men de manded vengeance in the form of other battles and more deaths.

Bitter hardships attended the conquistadores. Flocks and herds suffered losses from scarcity of water and forage. The overloaded horses became exhausted and many had to be abandoned. Many men were killed by resisting natives, or died from exhaustion. The party no longer resembled the brilliant cavalcade which had passed in review before the viceroy.

When they arrived at Cibola they could not rest but were forced into battle by the Zunis. After loss of many men, Coronado himself suffering wounds, the village was taken.

The soldiers marched into the first of the Seven Cities, and found neither gold nor splendor, only a few hundred families of poor Indians living within earthen pueblos. Maledictions were heaped upon the head of Fray Marcos whose blunder had led them on a wild goose chase across hundreds of miles of arid wilderness.

When headquarters had been established, other rumors of golden places drifted to the soldiers, stories probably invented by the Zuni in the hope that their conquerors would move on. Again excitement mounted, and the adventurers believed that riches truly lay to the east, the north, and west. Ironic circumstances had already led them unsuspecting, over vast mineral treasures which would not begin to be discovered for nearly half a century.

Rumors were spread concerning a rich, warlike people living twenty-five leagues to the northwest. This proved to be a region of high mesas overlooking a Painted Desert-Tusayan home of the Hopi Indians, who were neither rich nor very warlike.

Under the leadership of Don Pedro de Tovar, a small company of horsemen was sent into this country. They surrounded one of the villages secretly, under the shelter of night. In the morning a battle was fought and the pueblo taken. The whole province surrendered and the villages were thrown open to the invaders. There was no gold, however; the natives could pay tribute only in foods, skins, and cotton cloth.

While in Tusayan, Don Pedro heard of a mighty river lying further to the west, and carried the report back to Coronado. Coronado ordered Don Lopez de Cardenas to take twelve horsemen and search for this river. A chronicler who accompanied the party reported that after twenty days they came to the canyon of this river, but were unable to descend to the stream. Thus did disillusioned seekers after wealth survey the incomparable splendor of the Grand Canyon three centuries before Anglo-Saxons were to see it.

Coronado himself led an expedition across seemingly endless plains in search of the fabulous Quivira, "an Indian city where all was pure gold." With a small party of men he crossed the Arkansas River and progressed as far as north western Kansas. He found nothing but hardship and failure the nomad, buf falo-hunting tribe of Quivira Indians had no gold-but he had penetrated the con tinent three-fourths of the distance from the Gulf of California to the present site of New York.

Early in the Spring of 1542, a weary, starving band started back to civilization. The viceroy, having not only lost his own personal fortune on the venture, but incurred the displeasure of the King, received Coronado coldly. Shortly after ward, Coronado sold his governorship and retired to his estate. His work for history was finished.

After Coronado's invasion long silence settled over the desert again. The Indians tilled their land and warred among themselves without the terrifying thunder of arquebuses and howitzers. The story of the conquistadores became one of the legends told around Indian camp fires. More than a generation passed before another white man came.

Then came the sound of guns and horses again; soldiers and priests came holding the cross before them. The wild wilderness was forced to awake and listen. Indian chiefs sent out messengers to tell neighboring villages that the white men had come again, until the whole South west knew of his coming.

Don Antonio de Espejo was leading a

MAY, 1937 ARIZONA HIGHWAYS

small band of soldiers, priests and friendly Indians northward. These men were not looking for cities of gold, or expecting to find yellow metal shaped into beautifully carved vessels and statues. They were looking for mines, places where ore might be dug and transported back to Mexico for smelting. The Indians were not hostile; Espejo brought them trinkets instead of demanding tribute. After much wandering he came to a place near the present site of Prescott where the hills were rich with silver ore.

Espejo's success excited other explorers and many expeditions went into the wilderness, establishing garrisons. Farms and villages were established in fertile areas. Juan de Onate headed the largest of these expeditions. The Indians were no longer friendly, sensing their destruction unless the white settlers could be driven out. In a battle with the fierce inhabitants of Acoma, (in the present state of New Mexico) their “impregnable” walled city, built high on a rocky mesa, was taken in hand-to-hand fighting. The pueblo Indians were subdued. Before returning to Mexico, Onate went on an expedition looking for the sea that he knew lay to the west. His path led him across Arizona.

The work of the conquistadores was finished. Tales of easy wealth had been proved untrue. Thousands of miles of desert and mountain country had been explored and conquered. Trails from Mexico to Santa Fe, to the Pacific and to the large Indian villages had been worn for people of the succeeding years to follow. The Indians had been in a measure subdued, thus simplifying the advance of colonization.

A more humane and cultural era was established by good Padre Eusebio Kino, a Jesuit missionary. His superiors had assigned him to Pimeria Alta, the region which is now northern Sonora and southern Arizona. Here he began twenty-five years of missionary life that were to make his name immortal. This Tyrol-born priest was more than a spiritual father; he was a builder, discoverer, teacher, geographer, chronicler, and rancher. His courage was of a finer grain than that of the conquistador. He needed no firearms and no helmeted guard. Usually his only companions were a few Indians.

Even more permanent than the missions which he established was the spiritual good he did among the Indians of the Southwest. He gave the Roman Catholic tradition to the red men. Thousands were baptized and taught to read. Because of his friendliness, the Maricopa, Papago, Yuma, and Pima tribes were generally receptive to European culture. Father Kino gave them sheep and cattle from his mission ranches, and taught them how to develop and care for the herds.

These tribes offered no opposition to the later pioneers from the United States.

Almost a century before the Declaration of Independence was signed, Father Kino started cattle raising in Pimeria Alta. His efforts were the beginnings of one of the great industries of the Republic of the United States, not yet born.

Besides working with endless patience for the erection and development of Indian missions on the San Pedro and Santa Cruz rivers, Kino took many journeys to bring his religion to distant tribes. He was probably the first white man to look upon the Casa Grande ruins in the Gila Valley.

Father Kino died in 1711, and with him went the greatest missionary effort among the Indians. A few missionaries attempted to carry on, but they lacked his zeal and energy. Masses are still heard in the mission of San Xavier del Bac, near Tucson, of which he laid the cornerstone. This white building, containing age-mellowed relics of Spanish art, standing in the midst of a desert region, is a memorial to his name, and a symbol of Arizona's Spanish heritage.

When Kino no longer lived to direct personally the management of these missions, the cultivated land around them merged with the desert; sand and dust smothered the corn, and orchards perished. The Indians began again to war against the whites. The Jesuits were recalled.

The wilderness quickened again with the coming of the Franciscan Francisco Garces, in June, 1768. He planned for the rebuilding of San Xavier mission. He made long journeys to the tribes of the region, reawakening Christian beliefs, baptizing children and converts, and opening new trails for trade and com-

19

munication across Arizona between Sonora and the Pacific coast.

Near Yuma, on July 19, 1781, Garces was murdered by Indians he had believed to be his friends. Thereafter obscurity settled over the missions of Arizona. However the cultural, religious and material civilization of the Southwest still reflects the energy and self-sacrifice of three priests Fray Marcos, Padre Kino, and Padre Garces and a score of fellow priests, no less devoted, who sleep in unmarked graves on the desert that claimed their lives.

The American trapper came next upon the Arizona scene, and the eyes of the Mexican settler and the Indian were turned toward the vigorous Republic growing in the northwest. The centuries of Spanish dominion were drawing to a close, and the United States with its growing population was about to people the Southwest. After the Mexican War and the Gadsden Purchase, the American flag was raised over the territory, and the process began of welding two cultures, Latin and Anglo-Saxon in the land entered by Estevan hundreds of years before.

Planning Lengthy Highway Program

It was made. The topography through which the roads traversed was classified as flat or mountainous. All sight distances less than 1000 feet in flat country and less than 650 feet in mountainous country were measured. The length, degree and super-elevation was recorded on all curves over 2 degrees. Sight distance was obtained by stadia, an air-plane bank indicator was used to mea-

ARIZONA HIGHWAYS MAY, 1937

sure super-elevation, and an apparatus designed by this department was attached to the drag-rod of a car to measure the 'degree of curve.

In connection with the road inventory, a one-inch to the mile map is being compiled at an estimated cost of $20,000, exclusive of field work. This will doubtless be the only reliable large scale map in existence covering the entire state. Besides showing the conventional data of roads, land grid and physical features, it will show dwellings, farms, business places and other data gathered by the field parties. The map is being made on a polyconic projection on work sheets covering one degree of longitude and thirty minutes of latitude. The land grid is located by means of ties between U. S. G. S. triangulation points and township or section corners. After locating such ties on the work sheets, the intervening space is filled in by using the distances and bearings as shown on the General Land Office township plats, being somewhat similar to the piecing together of a jig-saw puzzle. The tie-in between known points was usually remarkably close except in areas where the land survey was made in the 1870's and '80's such as in the vicinity of St. Johns.

The tracings from the work sheets are made up into county series, there being of course several sheets to each county. The sheets are 36 inches wide, and average about 66 inches long. This department, besides using information secured by the field parties, has assembled probably the largest collection of maps in Arizona. All that are deemed authentic are used: U. S. G. S. maps, Forest Service, Indian Service, Reclamation, river surveys, railroad right-ofway maps, state highway, city plats, all subdivision plats, aerial photography maps, military and many other sources of different information that are required. By use of WPA tracers, 2500 copies of G. L. O. township plats were made.

On the base tracing, the roads are shown in open bands. From this, three series will be reproduced on tracing cloth. By means of filling in the open bands with the proper legend, these different series will show highways and type of surface, truck and bus routes, and U. S. postal routes.

The traffic survey division of the Planning Survey is much more than the usual routine count of motor vehicles. It not only embraces the State Highway System, but also covers the entire rural or county road system as well. The traffic survey is divided into four branches: Key Station count, Blanket count, Loadometer survey and Pit-scale survey. Key stations are so called because they are the key to major breaks in traffic density on primary roads. There are 72 such stations, all located on the State

HONORED

J. F. McSwain, widely known in construction and industrial circles, was elected chairman of the Asphalt Institute's Pacific Coast Division at a meeting of the board of directors in San Francisco recently. Mr. McSwain is manager of the asphalt department of Shell Oil Company.

The Asphalt Institute has just opened a new office in Los Angeles and is extending its work through Arizona.

"The Institute is planning a full program of educational and technical work for the coming year," Mr. McSwain said. "A very fine technical department is being developed which will assist engineers and others who have occasion to use asphalt in any form." Highway system, and nearly all located at junctions of important highways. The density counts at these stations are in eight-hour periods. A year's schedule was arranged in such a manner that each station will receive a 24-hour count on each day of the week. The counts are staggered so that they will reflect the average daily traffic for any season of the year.

The density information is recorded in hourly groups, giving the number of vehicles, segregated as to local or foreign, and each divided as to type, such as passenger cars, cars with house trailers, light, medium and heavy trucks, tractor truck-semi-trailer, truck and trailer, and busses.

The blanket count stations are density stations located on county roads. There are about 1,200 such stations, covering practically every road intersection in the At some, only one eight-hour count from 8 a. m. to 4 p. m., was taken. At others, depending on their importance as ascertained by the first count, additional counts were taken to establish proper ratios of seasonal fluctuations. Still others are maintained as control stations in different areas, from which several 24-hour counts are recorded. These are used to obtain proper factors in raising the eight-hour counts to a 24-hour period.

At the blanket count stations, origin and destination studies were also made. Cars were stopped and inquiries made as to point of origin and destination of that particular trip. The purpose of this study is to find out the routes that are more generally used between certain points, and to use such data for highway relocation if certain routes are found to be too indirect. After all the blanket count data has been assembled and tabulated, it will be possible to say definitely what the average daily traffic is on every mile of road in the state.

The loadometer survey, as the name indicates, is a study of traffic by use of loadometers, or portable scales. This is confined to truck and bus traffic on the State Highway System only. There are 36 loadometer stations, operated by three parties working in eight hour shifts, 6 a. m. to 2 p. m.; 2 p. m. to 10 p. m.; and 10 p. m. to 6 a. m. Like the key stations, schedules are arranged so that samples are taken to reflect each hour of the day, each day of the week, and each season of the year. Information obtained is: state in which truck or bus is registered, number of license plates, license number, type of truck, type of body, origin and destination, trip distance, commodities carried, type of origin and destination, that is, packing shed, depot, warehouse, etc.; axle weight, empty weight and carried load.

The purpose of this particular survey is to ascertain the wheel loads the roads are carrying, so as to supply data for paving and sub-grade design-to determine the relative responsibility of the various vehicle groups for the payment of road construction and maintenanceto provide a basis for traffic regulation as to weights and speed, and finally, by the additional means of the origin and destination, commodities carried and trip mileage data, a clear picture may be had of the State Highway as a transportation system, and the relative importance of each of its component parts.

At each of the loadometer stations, franked postal cards were passed out to passenger car drivers, with spaces to be

LEE MOOR CONTRACTING COMPANY

807 BASSETT TOWER EL PASO, TEXAS

ARIZONA HIGHWAYS

MAY, 1937 filled in as to origin and destination, qualified as to whether the origin or destination was rural or urban, and the place of ownership of the car. Thirty-five thousand such card were passed out, with about a 25% return. The fourth division of the traffic survey is the pit-scale survey. There are three pit-scale stations, one near Tucson, one at Gila Bend, and one at Morris-town. They are of 30-ton capacity, with 34-foot platforms, operated by a party of four men. This crew works at cach location for a period of three weeks, moving after the completion of the schedule, to the next location. The total operation calls for 18 weeks at each station. The information collected is similar to that of the loadometer stations, plus the additional data as to the number and size of tires on each truck, overall height, width and length, wheel base, distance between tandem axles, and manufacturer's rated capacity. The purpose of this survey is about the same as the loadometer survey, except that it will establish beyond any doubt the actual dimensions, weights, wheel loads, axle combinations and other characteristics of commercial vehicles. Special emphasis is placed on the comparison of a truck manufacturer's rated capacity and its actual carried load, as well as the unladen weight of a truck as compared to its carried load. This is of particular importance to Arizona, as unladen weight is the basis of license fees. It is evident that a light truck reinforced to carry six or eight tons is not as heavy as a truck with a manufacturer's rated capacity of six or eight tons.

Still another aid is gathering data on traffic flow is the use of automatic counters. They are designed to count passing vehicles without counting pedestrians. This is accomplished by two parallel beams of light directed across the roadway upon photoelectric cells. Interruption of both light beams by passing vehicles actuates a photoelectric relay which, in turn, operates the recording mechanism. The recording mechanism prints on tape once every hour, recording the hour, day, and the cumulative traffic total. There are seven such machines located at wide intervals on the main highways. Their main purpose is to furnish a continuous count and to form a basis for correction of related stations that are counted manually at widely separated time intervals.

It has perhaps been noted that in all phases of the traffic survey, considerable emphasis has been placed on origin and destination study. As already stated, one purpose of this is to provide data for the relocation of indirect routes. It will also establish the character of traffic as to the percentage of rural and urban, and settle questions as to the range of traffic over various classes of highways. It will establish what roads are The principal city to city routes, what roads are country to city, and vice versa. All these will have bearing on solving problems of equal taxation of highway users.

While the inventory and traffic survey are in the main a physical survey of the road system, the Financial Survey is economic. It in turn has three general divisions, namely: Financial Study, Road Use, and Motor Vehicle Allocation. The Financial Study is the compilation of data on the source of all forms of taxation, the total receipts and disbursements and distribution of all state governmental units. Accountants are now securing this data in the various counties, cities and state offices. The purpose is to reveal the relation between the sum of all highway revenues and expenditures and the total of all revenue and expenditures. It will establish the proportion of governmental cost that the motor vehicle owner is paying. It will indicate to what extent the countles, cities and state will be able to pay for future highway construction and maintenance. It should be stressed that no unit of government should build roads that it cannot afford to maintain properly.

The Road Use Survey is a study of the driving habits of motor vehicle owners, secured by personal interviews with representative owners. Twenty-five-hundred passenger car and one thousand truck owners will be interviewed by a trained staff of interviewers. Care will be exercised so as to secure a true cross-section of all classes of motor users over the state. Data obtained from a particular owner will be total miles traveled in the preceding twelve months, divided into miles traveled on the Federal Aid Sys-tem, State System, rural roads and city streets. It will be ascertained to what extent city dwellers use other highways in addition to their city streets, and, conversely, will also show to what extent rural dwellers use city streets. It will attempt to answer the basic question of what use is made of the streets and highways by those who pay for them.

The third division of the Financial Survey is known as the Motor Vehicle Allocation study. It is devised to obtain information relative to motor vehicles, motor vehicle registration, and motor fuel tax payments, in addition to the knowledge which may be gained from records kept by the State. The object is to get the following data classified by counties, and by rural and urban areas: Total miles traveled in past 12 months, total miles in Arizona, miles per gallon, occupation of owner, and make and model of vehicles. The data is obtained by use of franked postal cards distributed by county assessors when issuing 1937 license plates. The purpose is similar to that of the Road Use study. It also seeks to establish to what extent certain groups of owners are using the highways. It will furnish data on the average age of cars, the average yearly travel, and the amount of gasoline tax paid by a representative group.

All the mass of data obtained by the various branches of the Planning Survey will be assembled and punched on tab-ulating cards. Many Tables will be compiled and published, together with a complete written report. Due to lack of space, and to avoid BurdenIng The reader with details, some of the phases of the Planning Survey have been described but briefly, while there are others that have not been men-tioned at all. However, it is hoped that this paper has managed to convey some idea of its scope, its purpose, and its value for the planning of a long-range highway program.

The Unique Magazine Of the Inland Empire Arizona Highways

$1.00 Per Year

Already a member? Login ».