"66"

The Scenic

Seldom in this country has a highway been originally laid out by men riding on camels, but in Arizona, U.S. Highway 66 has that distinction. Lieutenant Beale, in 1857, crossed what is now Arizona, under orders to lay out a wagon road along the thirty-fifth parallel. He used camels as well as horses to ride or to pack equipment and supplies.

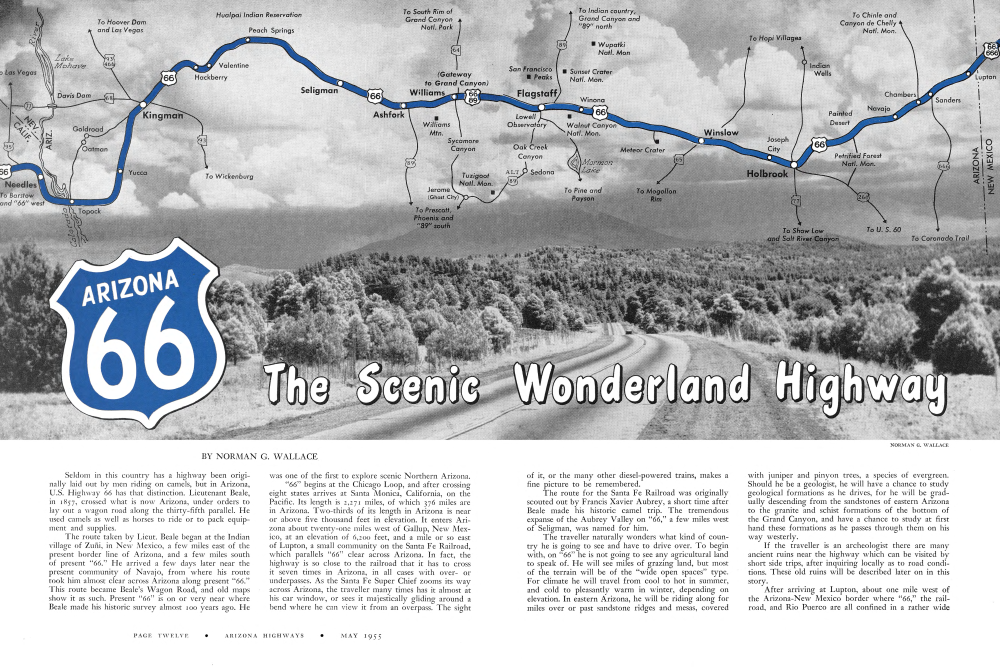

The route taken by Lieut. Beale began at the Indian village of Zuni, in New Mexico, a few miles east of the present border line of Arizona, and a few miles south of present "66." He arrived a few days later near the present community of Navajo, from where his route took him almost clear across Arizona along present "66." This route became Beale's Wagon Road, and old maps show it as such. Present "66" is on or very near where Beale made his historic survey almost 100 years ago. He was one of the first to explore scenic Northern Arizona. "66" begins at the Chicago Loop, and after crossing eight states arrives at Santa Monica, California, on the Pacific. Its length is 2,271 miles, of which 376 miles are in Arizona. Two-thirds of its length in Arizona is near or above five thousand feet in elevation. It enters Arizona about twenty-one miles west of Gallup, New Mexico, at an elevation of 6,200 feet, and a mile or so east of Lupton, a small community on the Santa Fe Railroad, which parallels "66" clear across Arizona. In fact, the highway is so close to the railroad that it has to cross it seven times in Arizona, in all cases with overor underpasses. As the Santa Fe Super Chief zooms its way across Arizona, the traveller many times has it almost at his car window, or sees it majestically gliding around a bend where he can view it from an overpass. The sight

Wonderland Highway

of it, or the many other diesel-powered trains, makes a fine picture to be remembered.

The route for the Santa Fe Railroad was originally scouted out by Francis Xavier Aubrey, a short time after Beale made his historic camel trip. The tremendous expanse of the Aubrey Valley on "66," a few miles west of Seligman, was named for him.

The traveller naturally wonders what kind of country he is going to see and have to drive over. To begin with, on "66" he is not going to see any agricultural land to speak of. He will see miles of grazing land, but most of the terrain will be of the "wide open spaces" type. For climate he will travel from cool to hot in summer, and cold to pleasantly warm in winter, depending on elevation. In eastern Arizona, he will be riding along for miles over or past sandstone ridges and mesas, covered with juniper and pinyon trees, a species of evergreen. Should he be a geologist, he will have a chance to study geological formations as he drives, for he will be gradually descending from the sandstones of eastern Arizona to the granite and schist formations of the bottom of the Grand Canyon, and have a chance to study at first hand these formations as he passes through them on his way westerly.

If the traveller is an archeologist there are many ancient ruins near the highway which can be visited by short side trips, after inquiring locally as to road conditions. These old ruins will be described later on in this story.

After arriving at Lupton, about one mile west of the Arizona-New Mexico border where "66," the railroad, and Rio Puerco are all confined in a rather wide canyon with brown, white and red sandstone cliffs rising hundreds of feet almost vertically on both sides, “66” enters Arizona at an elevation of 6,200 feet above sea level. As the traveller proceeds southwesterly he notices at frequent intervals Navajo Indians riding horseback or in wagons and trucks along trails parallel to the highway. As the highway is in the Navajo Indian Reservation for the first twenty miles in Arizona, he will see many of the Navajo hogans, or houses, scattered along the adjacent terrain. These hogans are round in shape, with a hole in the roof for a chimney, and are made of heavy juniper or pinyon logs, with the spaces between filled with mud. If close attention is given it will be seen that in all of the hogans the doorways face east.

There are service stations, curio stores and other facilities scattered all along this part of “66,” so the traveller will not lack for services when they are needed. At Sanders, which is about twenty miles west of the New Mexico border, and at an elevation of 5,836 feet, the Arizona State border inspection station is located, having recently been moved from Lupton. Also at Sanders is the junction of Highway 666 and “66.” Highway 666 is paved to St. Johns, Springerville and Alpine, in the heart of the White Mountain country, where, at 8,000 feet elevation or higher, there are vast expanses of pine and spruce forests, as well as clear-running streams and rivers, where rainbow trout abound. Should the traveller have time, he can try out Big Lake, not far from Alpine, and fish for one of the seven pound trout there, or he can go out from Springerville and try the Little Colorado River, or White River near McNary, and other streams for the shiny rainbow.

About four miles west of Sanders is Chambers, ele-vation 5,760 feet, where there is a junction with the road north to Ganado and Canyon de Chelly in the Navajo Indian Reservation. Ganado is about 43 miles north of Chambers and is the headquarters of a Presbyterian hospital for the Navajo Indians, and also has a large trading post where many fine Navajo rugs and jewelry may be seen. It is only another 42 miles to Chinle, a trading post for the Indians, as well as the National Park Monument headquarters for Canyon de Chelly. This canyon is noted not only for its spectacular scenic effect, but also for its many archeological ruins and cliff dwellings. Some of the cliff dwellings are so high above the bottom of the canyon that they look like swallows' nests, and make one wonder how the occupants got home after a trip to the bottom for water, or to cultivate the fields between the high cliff walls. The walls of the canyon rise 800 feet vertically without a break, or even at times lean over so that, where there are recesses in the canyon wall, ancient villages were built, protected by the overhang hundreds of feet above. The White House Ruin is such a village, and, due to the overhang of the cliff above it, has existed for many hundred years without destruction by rainfall and erosion. Here is in reality an ancient village, high and dry. At its foot and above the water in the canyon is another collection of stone houses in ruins, due to its lack of protection from weather. All up and down the canyon are other signs of prehistoric people and their homes. Canyon de Muerte is a branch of the main canyon and contains similar ruins. Now and then the silence is broken by the sound of the Navajo dogs barking while they attend the sheep, and their sharp barks echo for miles from one side to the other of this mighty gorge, although the dogs may be out of sight in the immen-sity around them. The canyon bottom is very sandy, and extreme caution must be used to keep from bogging down in the loose sand. Both of these canyons are well worth a visit, and the scenery, Painted Desert and Navajo Indians along the road make the Chinle side trip a very interesting one.

After leaving Chambers, "66" gradually comes out into the wide open spaces of the northern Arizona pla-teau, still at elevations above 5,500 feet. Up to about four miles west of Chambers, "66" has been modernized all the way from the state line, with wide asphaltic paving, easy curvature and grades. From there westward the highway is being modernized as fast as possible because the daily traffic count indicates a total of almost 3,000 cars per day, which calls for a wide and carefully planned highway. Eight miles from Chambers is the community of Navajo, near which Arizona had its first territorial officers sworn in, in December, 1863. It was near Navajo that Beale's trail from Zui tied on to where "66" now goes and from where he continued westerly along its present route clear through to beyond Kingman, 292 miles away.

After going over some open grass-covered mesas, the Painted Desert and Black Petrified Forest are reached, nineteen miles west of Navajo and at 5,800 feet elevation. This spot is the northern extension of the main part of the Petrified Forest National Monument and from the lodge and rim drive adjacent to "66," a fine view is obtained of the red, yellow, blue and white formations of the Painted Desert below, and to the north. The side road along the rim connects with "66" again, in about two miles, and to the junction with the paved branch highway leading to the Petrified Forest. By taking this side road, the traveller will see all of the wonders of the Petrified Forest as he rides, or takes the several paved roads to special points of interest such as the Blue Forest, Petrified Log Bridge and museum at the head-quarters of the National Monument. Many petrified logs lie in scattered profusion along the way, in sections of several tons weight, or in places sticking out of the ground where they originally came to rest and after millions of years were petrified. The side trip to the main Petrified Forest is well worth the extra 17 miles of distance travelled, as from near the headquarters museum, Highway 260 leads to Holbrook only nineteen miles away, and to "66."

Holbrook, a city of several thousand people, has many facilities to take care of the traveller, such as motels, restaurants, garages and service stations, where he can, if necessary, prepare for his journey farther westward, as he still has 302 miles to go on "66" in Arizona. Holbrook is also the junction of two paved highways leading to the towns of eastern and southern Arizona and one road leading northward into the Navajo Indian Reservation, and to the famed Hopi Indian villages atop the high mesas, about 100 miles away, where the Snake Dance is held every year. Highway 77 goes directly south from Holbrook through the old Mormon settlements of Snowflake and Taylor and to Show Low, where it joins U.S. Highway 60, which is itself a fine scenic highway to Globe and Miami, the mining centers of central Arizona. The Salt River Canyon is crossed by Highway 60 and is a miniature Grand Canyon with exceptionally fine scenery. Also, southeast of Holbrook, Highway 260 connects eastern Arizona with "66," and joins Highway 666 at St. Johns. The high mesas east of Holbrook on "66" afford a magnificent panorama of the White Mountains, snow covered, 75 miles to the south, and of the vast expanse of mesas as many miles to the north. This part of "66" is practically treeless and gives the traveller an idea of the tremendous open spaces of the plateau of Northern Arizona.

After leaving Holbrook, "66" goes through some curious red sandstone knolls and low mesas until Joseph City, twelve miles away, is reached near the north bank of the Little Colorado River. Joseph City is an old Mormon settlement and along the highway will be seen practically all of the agricultural ground to be seen along the whole length of "66" in Arizona. The shade trees along the main street of Joseph City resemble a small oasis in the treeless spaces along this part of Highway 66, and are irrigated, as well as are the farms, by water from the Little Colorado River nearby. After 32 miles of good paved highway over rolling treeless ground, "66" crosses the wide, sandy Little Colorado River, where often the water only flows beneath the dry sandy bottom, or shows a mere trickle at most. However, it can flow heavily after storms or melting snows from the White Mountains.

A mile or so west of the Little Colorado River bridge is Winslow, another city of several thousand people, at 4,850 feet elevation, the lowest point on Highway 66 so far in Arizona, which does not reach lower elevations for the next 170 miles. Winslow is mostly a railroad town, as it is a division point on the Santa Fe Railroad, with shops and a large freight yard. However, the lumber industry has arrived at Winslow, although the traveller

COLOR 66 DATA

"THE WOODPILE" BY CARLOS ELMER. This spot is found in the Blue Forest scenic loop drive in Petrified Forest National Monument. The photographer says: "I was impressed by the seemingly untouched nature of the scene, as though some giant wood-chopper had just left the spot, leaving neat lengths of wood and chips. After visiting this spot, I was angry upon hearing a person boast of his cleverness in stealing a piece of petrified wood from the Monument. I can only hope that such a person is a rarity, and that this beautiful scene may look just like this 30 years from now."

"AIR VIEW, FLAGSTAFF AND SAN FRANCISCO PEAKS" BY DON KELLER. This dramatic view of Flagstaff and the Peaks was taken at 15,000 feet above sea level. The exposure was tenth of a second at stop f.8, 4x5 Speed Graphic, Eastman wide field Ektar f.6.3, 135mm lens.

"MOENCOPI IN HOPILAND" BY ESTHER HENDERSON. This checkerboard farm scene was taken just east of the Hopi Indian village of Moenkopi where the seemingly sparse plantings belie the abundance of the corn yield. Indian harvests are generally scant but the fertile soil and water from Moenkopi Wash make this a comparatively bountiful valley. Photographed in mid-August; 5x7 Deardorff view camera, Ektachrome film, Goerz Dogmar lens, 1/10 at f.25.

"SUNSET CRATER" BY ESTHER HENDERSON, Sunset Crater, the red-rimmed cinder cone eighteen miles east of Flag-staff, presents a different shape from various directions. From the east side it appears to have a pointed top; from the south, a squat roundness; from the northwest, as in this view, it shows its symmetry because the photograph was made from a location high enough to look into the hollow at the point where the crater lip curled down to spill its ancient contents. Photographed about 4 p.m. in midsummer, 5x7 Deardorff view camera, Ektachrome film, Goerz Dogmar lens, 1/5 at f.22.

CENTER PANEL

"SEDONA, THE RED ROCK COUNTRY" BY RAY MAN-LEY. The Sedona country is just a few minutes' drive from "66." This view shows the magnificence of the red cliffs as well as the dramatic qualities of the farms about. "In this scene," the photographer says, "I waited until the farmer was in the middle of the scene. It seemed to me his appearance in the picture added emphasis to the spaciousness of the surrounding country. I wanted to emphasize that."

COLOR 66 DATA

Traveler will look without success for the sight of a pine tree. The lumber is made out of logs from the immense stands of yellow pine on the Mogollon Rim fifty miles to the south, from where they are trucked to the Winslow saw-mills. The livestock industry also thrives all around Winslow as there are thousands of square miles of good range on both sides of "66," as well as the cattle, sheep and wool from the vast ranges of the Navajo Indian Reservation to the north. Many Navajo Indians may be seen on the streets of Winslow. They are employed by the Santa Fe Railroad in the shops and along the tracks on section gangs. Winslow has several trading posts where an abundance of Navajo rugs

COLOR 66 DATA

"66' NEAR WILLIAMS" BY NORMAN G. WALLACE, Over this highway, one of the busiest cross-state highways in Arizona, pass nearly 3,000 vehicles a day. This scene is near Williams look-ing toward Bill Williams Mountain. The highway here is 22 feet wide with seven-foot shoulders, a modern Arizona highway built to handle a heavy load of traffic.

"GRAND CANYON" BY CHUCK ABBOTT. This is the eastern rampart of the Grand Canyon at Desert View where the river runs smoothly through a comparatively wide canyon and the view across the rim stretches away to the infinity of Indian lands. Not far from here, the Little Colorado cuts a knife-edge through the plateau beyond the rim before joining the mighty Colorado a few miles upstream from this point. Photograph taken near sunset. 5x7 Deardorff view camera, Ektachrome film, Bausch & Lomb lens, 1/5 at f. 22.

"BIG SANDY NEAR KINGMAN" BY CARLOS ELMER. This scene was made at the spot where U.S. 93 crosses the Big Sandy River below Wikieup. The new highway, now under construction between Kingman and Congress Junction, will open up this scenic part of the state when completed. The route is quite usable in its present form, and even now represents a considerable saving in time over other available routes.

"SYCAMORE CANYON" BY CHUCK ABBOTT. Few people are familiar with Sycamore Canyon although it lies just west of Oak Creek and is eroded from the same red sandstones to form the same spectacular type of scene. This is one of Arizona's wilder-ness areas, uncrossed by road or trail-a wildlife refuge and habitat of big game. This is not a remote place lying, as it does, only twenty-three miles south of Williams, but it remains almost inaccessible to the average visitor except at this point along the rim reached via the White Horse Lake road. Photographic time for this scene is morning when the formations are thrown in relief; access roads are safe but unmarked and seldom-used. 5x7 Deardorff, Ektachrome film, Goerz Dogmar lens, 1/5 at f. 25.

OPPOSITE PAGE "THE GOLDEN JOSHUAS" BY CARLOS ELMER. "During late afternoon on an April day I came across this scene in Mohave County's great Joshua forest, north of Kingman, on the road to Pierce Ferry," the photographer says. "I have visited all of the various Joshua forests found in Arizona, California, and Nevada, and I prefer this one to all others because of the thickness of growth and the much greater height of the Mohave County trees. Of course, this just may be pride in my home county, much like the incident when my friend from Houston introduced me to a midget who was 5' 2½" tall, explaining merely that Texas had the largest midgets in the world."

COLOR 66 DATA

and jewelry is on sale and are well worth a visit for their educational value alone. There is also a good supply of Hopi Indian pottery and basketware available for purchase. Needless to say, Winslow affords all kinds of services to make a stop-over comfortable, or prepare the traveller for the road ahead.

After leaving Winslow, "66" has been rebuilt to the latest highway standards and some fine highway over the rolling mesas of this part of Arizona is swiftly gone over. We are still in the treeless part of the plateau region and sixty miles to the west the San Francisco Peaks, nearly always snow-capped, dominate the western horizon.

Seventeen miles west of Winslow, "66" crosses the Santa Fe Railroad by means of a new overpass at Sun-shine, and after going another three miles past some odd-looking, red sandstone knolls with flat tops, comes to the junction of a good road leading to the Meteor Crater, seven miles to the south. This crater is almost four thou-sand feet wide and about six hundred feet deep, suppos-edly having been made by the impact of a huge mete-orite, or swarm of them, striking the earth with such force as to make a wide and deep hole in the ground. As a great many pieces of meteorites have been found all around Meteor Crater, this theory seems to account for the large cavity. By visiting the crater itself and then the Meteor Crater Observatory at the junction of the crater road and "66," a great deal of information may be obtained. From the observatory, Meteor Crater looks like a long whitish ridge jutting up out of the barren plain to the south.

Four miles west of the Meteor Crater road, "66" crosses a rather spectacular crevasse called Canyon Diablo, which, when encountered by Lieutenant Beale on his survey in 1857, forced him to detour several miles to the north before he could cross it with his camels and wagons. The Santa Fe Railroad has an imposing high steel bridge over Canyon Diablo which may be seen by taking a side road from "66."

For the next seven miles, "66" goes almost straight ahead over a treeless but grass-covered rolling plain, and then suddenly enters the juniper and pinyon forest which grows heavier as Padre Canyon is crossed. This canyon is over 100 feet deep and requires a fine arch type steel bridge to cross over. From Padre Canyon, "66" gradually enters the heavy pine forest of northern Ari-zona, and does not emerge from it for almost 60 miles. This pine forest is considered to be the largest unbroken pine forest in the United States, and it lies like a belt clear across Arizona from southeast to beyond the Grand Canyon on the northwest.

The finest part of "66" now unfolds as the traveller is going from east to west. For almost sixty miles the tall pines are on both sides of the highway, and with the many vistas of the snow-capped San Francisco Peaks between the green trees, the traveller will have some-thing to remember.

From Winona, about eight miles west of Padre Canyon, "66" is built of concrete for more than forty miles westward. The concrete is almost one foot thick and the shoulders of the roadway have been built wide and made with an asphaltic surface, so that a car may have room to park along the roadside. About seven miles west of Winona, the Santa Fe Railroad is crossed by an overpass in the forest, from where the San Francisco Peaks make a fine picture.

As the traveller approaches Flagstaff he will come to a junction with U.S. Highway 89 going north toward Cameron, the Colorado River, Kaibab Forest, and to Utah. On "89" north of Flagstaff there are several points of interest to be seen close to Flagstaff, such as Sunset Crater, the Wupatki Ruins and Cameron on the Little Colorado River, also the Hopi village of Moencopi and Tuba City. "89" also has a junction, near Cameron, with Highway 64 which leads to the Grand Canyon itself.

Flagstaff or Kinlani, the Big City, as the Navajo Indians call it, is 7,000 feet above sea level and lies almost at the foot of the San Francisco Peaks. From Flagstaff there are a number of very interesting side trips to be taken. Right in town almost, but high up on a hill, is the famed Lowell Astronomical Observatory where much scientific information has been gathered. Several large telescopes or reflectors are there which have been used extensively for celestial observations, and where another planet, Pluto, was discovered. As there are so many interesting spots worth visiting not far from Flagstaff an overnight stay, or more, is desirable if one has the time.

One of the finest scenic spots close to Flagstaff is Oak Creek Canyon, on Alternate U.S. Highway 89 going south to Cottonwood, Jerome and Prescott. After going south about fifteen miles through a dense pine forest, the road comes to Lookout Point from which a panorama of Oak Creek Canyon below opens out with breath-taking suddenness. From Lookout Point the road 600 feet below looks like a small white streak shining between open spaces in the heavy forest on the canyon floor. After three miles of hairpin turns where the highway may be seen in three or more places below or above from the same spot, the road arrives at the bottom of the canyon. From here to Sedona, about thirty miles south of Flagstaff, the highway winds down a very colorful deep canyon, cut in the red, yellow and white sandstone by Oak Creek. At every turn in the highway another vista opens out, with the roaring creek always close by. An exceptional view is one looking up stream from Oak Creek bridge, where a good view of Oak Creek Falls, just above the bridge, is framed by the red and yellow cliffs rising 2,000 feet above the canyon bottom. About three miles south of Sedona where there is a good place to turn around and head back to Flagstaff, a general panoramic view may be had of the cliffs and high colorful mesas surrounding the community of Sedona. The entire round trip trip to beyond Sedona and return to Flagstaff may be made in a little over three hours and the extra time taken is well worth the side trip to Oak Creek Canyon. In addition to the superb scenery, there are many fruit orchards and gardens along Oak Creek, where delicious apples, pears, peaches and other fruit are grown.

From Flagstaff there are also many other side trips to be taken, such as to the Museum of Northern Arizona where there are fine exhibits of Indian culture, ancient and modern, as well as many other exhibits of various subjects to be seen in the vicinity of Flagstaff. Then there are the Walnut Canyon and Wupatki National Monuments which show ancient cliff dwellings and ruins of stone villages many hundreds of years old. Then in winter there is the Ski Bowl on the slopes of San Francisco Peaks, whose 12,670 feet high summits, nearly always snow-capped, predominate the northern sky. To the north there is the Sunset Crater National Monument where the crater always looks like it was reflecting the red light of a setting sun, even on cloudy days. This cinder crater can be climbed by those of adventurous nature and a fine picture of the Lava Beds and Ice Cave, below, may be seen. Sunset Crater is said to be only about 800 years old, and is very similar to the new volcano, Paracutin, in Mexico.

South of Flagstaff are the twin lakes, upper and lower Lake Mary, only nine miles away, on a good paved road. South of Lake Mary is Mormon Lake, six miles wide and a noted summer resort. The elevation being well over 7,00o feet, a heavy pine forest flourishes at Mormon Lake, and Mormon Mountain, nearby, also timber covered, reaches to 8,440 feet elevation. There are many small lakes near here where fishing is usually good. The entire Flagstaff area has so many points of interest that several days could be very profitably spent here. After leaving Flagstaff, Highway 66 is paved with concrete practically all of the way west to Williams, 32 miles away, and winds its way through the green forest with new vistas at every turn, with Bill Williams Mountain, almost 9,000 feet high, dominating the western horizon and with the ever-present San Francisco Peaks on the right, toward the north. An exceptional view of the San Francisco Peaks may be seen from a roadside park about 21 miles west of Flagstaff. About six miles west of Flagstaff, "66" crosses a high divide over 7,330 feet above sea level near the Riordan overpass on the Santa Fe Railroad. Twelve miles west of Flagstaff is the sprawling Navajo Ordnance Depot, with its storage houses for munitions in immense concrete igloos, called such on account of their resemblance to the Esquimau snow house. About two miles east of Williams is the junction of Highway 64, which leads straight north to the Grand Canyon, 57 miles away. Inasmuch as the Grand Canyon is so close to "66" no one should ever miss that inspiring sight if they are travelling on "66" past the junction with Highway 64. In fact, several days could be spent either in summer or in winter at the Grand Canyon as Highway 64 is kept open all of the year. Even if one is rushed for time, five or six hours extra will enable him to at least see the canyon and take side trip drives along the South Rim. However, he should stay over long enough to see a sunrise and sunset at the canyon. Williams, a city about 6,800 feet above sea level and 32 miles west of Flagstaff, is still in the pine forest, and has a lumber mill or two cutting up the pine logs from near by. From Williams, a good side road leads south through the dense pine forest to White Horse Lake, about twenty miles away, and to the rim of Sycamore Canyon, which is of the same type of scenic grandeur as Oak Creek Canyon. Williams has all facilities a traveller might need. The ever-present scent of the forest and the smell of the burning pine wood from the home fires make Williams a happy memory. After leaving Williams, "66" still winds through the pine forest to the top of Ash Fork Hill, ten miles away. From the top of this hill the view west is over a wide rolling plain dotted with juniper trees and grassy open places with Picacho Mountain like a pyramid overlooking the western rim. The pine forest stops suddenly at the top of Ash Fork Hill, and gives way to the wide spread juniper trees which continue for many miles. The Ash Fork Hill portion of "66" has just recently been rebuilt to a fine, wide highway, and the descent going west is made in a few minutes as most of the curves have been eliminated. Actually "66" has been dropping steadily from an elevation of 7,000 feet near Williams to an elevation of 5,300 feet just east of Ash Fork, but the Ash Fork Hill proper has a drop of 1,200 feet in less than six miles and this part is now gone over, either east or west bound, in a few minutes with room to pass slowly moving trucks.

Ash Highway 89 goes south to Prescott and Phoenix and joins Alternate Highway 89 near Prescott, and makes the main route to southern Arizona, via Congress Junction, Aguila, or Wickenburg.

Ash Fork is about 5,140 feet elevation with the Santa Fe Railroad almost right at the car window, and is another town where all travel facilities are available if needed. From Ash Fork west the highway rolls over some low juniper-covered ridges and wide grassy valleys for 15 miles, until it crosses the Santa Fe Railroad near Crookton with an overpass, and nine miles farther arrives at Seligman, elevation 5,250 feet.

Seligman is principally a railroad town, as it has a large freight yard and other railroad facilities, but the traveller can obtain anything needed for comfort, or a stay over if needed. The town is also the hub of a large ranching area.

About one mile west of Seligman, “66” crosses Chino Creek, where Beale in 1857 found water for his horses after wandering around a day or so looking for it. Just north of Chino Creek and near the long sandstone ridge coming toward the highway, the old trails of Beale's Wagon Road, deeply rutted, may still be seen, as they led to a spring at the foot of the red bluffs. Five miles west of Seligman both “66” and the Santa Fe Railroad are very close together as they go through a low saddle at Chino Point, where the high red and yellow sandstone cliffs end at Chino Pass.

About 8 miles west of Seligman, “66” descends into the wide, treeless Aubrey Valley, named for one of the pathfinders for the Santa Fe Railroad, who crossed the valley about 100 years ago. The highway is straight for almost 15 miles, passing through the grassy flats of Aubrey Valley where many cattle dot the rich feeding ground. Hyde Park, on a rise at the west side of Aubrey Valley, lies snugly in the juniper-covered hills which now appear across the path of the highway.

About 33 miles west of Seligman, “66” comes to a hilltop where a magnificent view of the country ahead may be seen. Looking northward, about 15 miles away, a long dark cliff seems to rise out of the jumble of mesas and juniper-covered ridges. This dark line is the rim of Grand Canyon where it is closer to “66” than anywhere else. About four miles farther Peach Springs is reached, a Hualpai Indian Reservation trading post and service station point. Here may be seen Hualpai Indian children going to school, and the grown-ups gathered around the stores. From the hilltop four miles east of Peach Springs, at an elevation of about 5,000 feet, “66” begins its gradual descent from the plateau of Northern Arizona to the desert region at Topock, at the western border of Arizona, on the Colorado River, 104 miles away. Ever since crossing the New Mexico border, “66” has been rolling along at high elevations near or above 5,000 feet, sometimes even up to 7,300 feet, but from Peach Springs the highway, although still in the juniper forest, will drop to the yucca desert of western Arizona.

About fifteen miles west of Peach Springs, “66” passes through picturesque Crozier Canyon, having dropped 800 feet in elevation, and then arrives at Valentine, where a letter or card may be dropped with that odd name for a postmark. After going through some odd granite boulder formations, one reaches the Hual-

Already a member? Login ».