THE LAST RUN

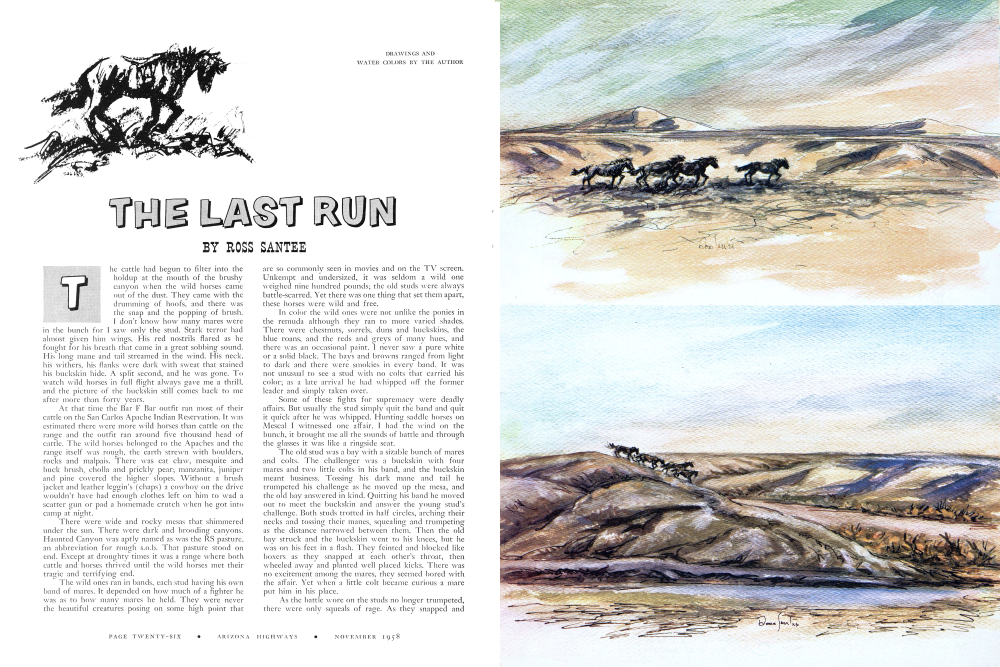

The cattle had begun to filter into the holdup at the mouth of the brushy canyon when the wild horses came out of the dust. They came with the drumming of hoofs, and there was the snap and the popping of brush. I don't know how many mares were in the bunch for I saw only the stud. Stark terror had almost given him wings. His red nostrils flared as he fought for his breath that came in a great sobbing sound. His long mane and tail streamed in the wind. His neck, his withers, his flanks were dark with sweat that stained his buckskin hide. A split second, and he was gone. To watch wild horses in full flight always gave me a thrill, and the picture of the buckskin still comes back to me after more than forty years.

At that time the Bar F Bar outfit ran most of their cattle on the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation. It was estimated there were more wild horses than cattle on the range and the outfit ran around five thousand head of cattle. The wild horses belonged to the Apaches and the range itself was rough, the earth strewn with boulders, rocks and malpais. There was cat claw, mesquite and buck brush, cholla and prickly pear; manzanita, juniper and pine covered the higher slopes. Without a brush jacket and leather leggin's (chaps) a cowboy on the drive wouldn't have had enough clothes left on him to wad a scatter gun or pad a homemade crutch when he got into camp at night.

There were wide and rocky mesas that shimmered under the sun. There were dark and brooding canyons. Haunted Canyon was aptly named as was the RS pasture, an abbreviation for rough s.o.b. That pasture stood on end. Except at droughty times it was a range where both cattle and horses thrived until the wild horses met their tragic and terrifying end.

The wild ones ran in bands, each stud having his own band of mares. It depended on how much of a fighter he was as to how many mares he held. They were never the beautiful creatures posing on some high point thatare so commonly seen in movies and on the TV screen. Unkempt and undersized, it was seldom a wild one weighed nine hundred pounds; the old studs were always battle-scarred. Yet there was one thing that set them apart, these horses were wild and free.

In color the wild ones were not unlike the ponies in the remuda although they ran to more varied shades. There were chestnuts, sorrels, duns and buckskins, the blue roans, and the reds and greys of many hues, and there was an occasional paint. I never saw a pure white or a solid black. The bays and browns ranged from light to dark and there were smokies in every band. It was not unusual to see a stud with no colts that carried his color; as a late arrival he had whipped off the former leader and simply taken over.Some of these fights for supremacy were deadly affairs. But usually the stud simply quit the band and quit it quick after he was whipped. Hunting saddle horses on Mescal I witnessed one affair. I had the wind on the bunch, it brought me all the sounds of battle and through the glasses it was like a ringside seat.

The old stud was a bay with a sizable bunch of mares and colts. The challenger was a buckskin with four mares and two little colts in his band, and the buckskin meant business. Tossing his dark mane and tail he trumpeted his challenge as he moved up the mesa, and the old bay answered in kind. Quitting his band he moved out to meet the buckskin and answer the young stud's challenge. Both studs trotted in half circles, arching their necks and tossing their manes, squealing and trumpeting as the distance narrowed between them. Then the old bay struck and the buckskin went to his knees, but he was on his feet in a flash. They feinted and blocked like boxers as they snapped at each other's throat, then wheeled away and planted well placed kicks. There was no excitement among the mares, they seemed bored with the affair. Yet when a little colt became curious a mare put him in his place.As the battle wore on the studs no longer trumpeted, there were only squeals of rage. As they snapped andstruck for each other's throat their popping teeth cracked like pistol shots. While the old bay knew every trick it was obvious that he was tiring as the buckskin, the younger and stronger stud, kept pressing the attack. Then suddenly it was over. The old bay stud broke and ran. While the buckskin did not follow he trumpeted long and loud, then rounding up both bands he headed them towards the water, nipping the flank of any mare he thought was a trifle too slow. At intervals he wheeled and tossed his head and the wind brought me his challenge.

When the old bay turned and ran he did not appear to be seriously hurt. It was a day or so later when another rider and myself rode onto the old bay's carcass less than a half mile from the scene of the fight. The death wound was in the throat. His neck, his withers, even his flanks were covered with scars that told of his battles over the years. It was obvious from the great scar that covered his breast that he had at one time crashed a wire fence. The signs showed too where blow flies had laid their eggs and added their torture to the wound. Blow flies laying eggs in a sore not only meant torture but often death to both cattle and horses on the range unless the wounds were doctored. Yet in some miraculous manner the great wound in his breast had healed.

We could only guess at his age. From the sockets above his eyes, his teeth and the white hairs in what had once been a black muzzle my pardner reckoned he might be from twelve to fourteen years, give or take a little. He wore no brand. In all probability he had never been touched by human hands, and he had more than earned his freedom.

It was not always the bigger and stronger stud who won the fight and took over his opponent's band. The outfit owned a brown stud that would go eleven hundred and fifty pounds; he ran with a band of picked mares up in the RS pasture. On riding the pasture one of the boys found the big brown stud alone and he had been thoroughly whipped. The stud was brought to the ranch where his wounds were doctored and a few days later the boys found his band of mares. The stud that had taken over was a knot-headed little thing that weighed no more than seven hundred and fifty pounds. He had not only given the big brown almost four hundred pounds in weight, he had whipped him to a standstill.

Barbed wire always took its toll with the wild horses on the range. Wrangling the big pasture one morning in the half-light I could hear the wild ones coming down the main ridge long before they came in sight. My pardner had jumped them out. The stud had moved into the lead as they often did when the wild ones were crowded and in full flight. It was a sizable band and I caught a fleeting glimpse of one of our pack mules. It was two years before the outfit got him back. They were out of sight when they crashed the back pasture fence and I heard a wild one scream. She was still struggling, torn and bleeding on the wire, when my pardner and I rode up. He put a merciful slug between her eyes. Apaches running the wild ones had run them over the fence and into the pasture.

In the fall while the Apache squaws gathered acorns to be ground into flour the bucks ran wild horses, usually to little purpose that I could see except for the sport itself. I witnessed many of these sashays.

Holding the remuda on the water at Mud Springs at noon one bright fall day I heard the drumming of hoofs. When I rode to the rise to investigate I could see the wild bunch coming and they veered sharply at sight of me. There were probably thirty in the band and the stud, a dark brown with a long mane and heavy tail, was at the rear urging his band to greater speed. Then six Apache riders hove in sight at least a quarter of a mile behind, and the riders were strung out for all of a hundred vards. I knew they had already lost their race as the wild ones were disappearing into the canyon below. But the riders kept coming on although their ponies were dinked, some had begun to weave; yet each rider beat a tatoo against his pony's paunch as he worked him over and under with the double of his rope. Each Apache yelped as he flayed his mount, the sound was not unlike the short, sharp bark of his brother, the coyote.

Occasionally the Apaches put on a big drive with as many as forty or fifty riders in attendance. They would meet at designated places. The holdup was usually at one of the natural corrals. But the Apache, always an individualist, acted on his own. It was not unusual to have a big bunch of wild ones trapped when one lone individual fouled the works. An old buck, in pursuit of one that caught his eye, yelping for all he was worth, came into the holdup on the dead run. In less time than it takes to write it down the wild ones would be scattered like a great covey of quail with each Apache in pursuit of a pony he wanted.

Any wild ones caught seldom if ever went to the wild bunch again, for the Apache had his own way of breaking a horse. A favored method in those days was to tie the wild one to a stout mesquite or tree for soveral days, giving him no water. Then the wild one would be led to the creek and allowed to drink his fill. With the pony's paunch full of water almost to the bursting point the Apache would saddle and step across. What with a paunch full of water, in sand halfway to his knees, the pony couldn't even crow hop. After a few such treatments he wasn't wild any more. It wouldn't be long until the squaw and kids would be riding and packing the pony.

With the exception of a few Spanish mare mules all the saddle horses and pack stock in the remuda were geldings. A gentle saddle horse or mule on going to the wild bunch became as wild as any wild one in the band.

Though the stud kept him whipped out of the inner circle the saddle horse would hang on the outskirts. Through the glasses I often observed a gentle old saddle horse giving affection to a little spindly-legged wild colt. All geldings seemed to love a little colt, following them about, fussing over them to a greater extent than the colt's mammy, who was always matter-of-fact. And when the outfit moved camp two punchers were sent ahead to run the wild ones out of that particular part of the country. It was only by running the wild ones out that we could hold our saddle horses at night.

At Soda Canyon two little colts came in with the remuda one morning. A mockey (wild mare) will seldom go back after a colt that has been left behind in their wild flight. The colts had found our saddle horses in the night and Rat, the cook's horse, had already taken over. He fought every horse in the remuda that came near the colts until old Slocum became conscious of their presence. Only then did Rat quit his charges for old Slocum was not only the leader of the remuda he was always boss as well.

The colts were too small to graze, they could only lap at water. Martin Woods was a cowboy on that work. "If we could only get 'em to my place my kids would raise them little fellers." But Martin lived at El Capitan, many rough miles from our camp. Martin knew there was no way of getting the colts to his place and they were shot. It was far more merciful than to let the littlefellows starve or be pulled down by the coyotes.

These little colts left behind were not an unusual thing on the range. Many cowboy chores were unpleasant but killing a colt was one of the sorriest I recall. For a colt is nothing but a horse in miniature. Trusting, he'd look at a horse and rider with shining eyes as if he had found a friend.

As horse wrangler I had much time to mess around on my own. It was customary for most wranglers to carry a greasy deck of cards and play solitaire. While the wrangler's duties were from sun to sun I was never bored. I ran the wild ones at every opportunity and to less purpose than most Apaches. I had acquired a pair of German field glasses in a poker game at Camp Bowie, Texas. The glasses saved a lot of horse flesh when I was hunting lost ponies and they brought me closeups of many things I might otherwise have missed.

At various places the wild studs left their droppings in huge piles; aside from the lack of straw or bedding they might easily have been mistaken for the manure pile behind any Iowa horse barn. I never saw a mare at one of these piles, it was always the different studs. In talking to George England, who was a mighty hunter of panther an' bear and a wolfer of local renown, he said the loafers, the lobos, had certain designated places where the dog wolves urinated. George surmised that the droppings had their own potent meaning to the studs and while he had often seen these piles he had never given it

caught and led out so many wild ones he was banned from the Reservation for a time. But fortunately for Steve in those days Indian agents came and went.

At the holdup one morning with Steve the wild horses fouled up the drive. Cattle coming down turned back and tried to rim out as the wild horses went racing through them, and there were several bands. The cattle had begun to filter into the holdup when I missed Steve.

The boys on the outside circle were in before he showed up. That we had lost half the cattle didn't bother my friend in the least. Steve had caught and tied down a wild horse that later proved to be locoed.

I was throwing the ponies together on the edge of the big mesa one evening when three wild ones came in and mixed with the saddle band. It wasn't long until Steve appeared, his pony dinked and weaving on his feet. "There's one good one," he said; "le'me ketch a fresh horse!"

We eased the ponies together so as not to disturb the wild ones. The remuda was held against a bluff, then Steve led out a big buckskin that was a top horse in the rep's mount who was riding for a neighboring ranch.

"Not him," I said, "if the owner, ever learned any-one ran mockeys on that horse he'd shoot the pair of us."

"Caught the proudest steppin' one in the bunch," said Steve as he saddled the big horse. "Any time ya steal a horse always pick a good one."

"You picked a good one, but let him break a leg an' we'll both have to quit the country."

"Think nothin' of it," said my friend as he swung aboard; "always look on the brighter side. Now ease them wild ones out an' watch me hang it on him."

Steve cocked his loop. I eased the wild ones out and the buckskin ran over two of them but not the one Steve wanted. That wild one could really run. After a quarter he was still going away and Steve finally called it quits. And now the real problem arose. While the buckskin hadn't broken a sweat he was wet from the saddle blankets and he was blowing hard. What complicated the matter was the fact that the rep was feeding grain; he'd hang a nose bag on each pony in his mount when we got into camp. He couldn't miss the fact that the buckskin had been ridden.

We rubbed him down but he was still blowing hard.

I threw the remuda together after Steve caught another horse, one from his own mount. It was now dark and we were long overdue. "This damn buckskin," said Steve, "is blowin' harder'n ever. Tell ya what le's do, le's take the remuda in on the run an' get 'em all to blowin', then the rep won't be suspicious. What's more they'll figger we been again' a Mason jar an' both of us is drunk."

There were about ninety head in the remuda and we brought them in on the run. Coming off the steep hillside that led to camp remuda bells were jangling as we squalled long an' loud. There was only one conclusion as far as the outfit went, Steve and I were drunk. The rep hung the nosebags on his ponies without suspecting anything. The wranglers had taken the ponies out when Steve looked at me and laughed.

"Now what the hell!" said Lin Mayes, the little foreman. "Why not cut us in on the deal? For two fellers as drunk as you was ya sobered up mighty quick."

Steve brought me paper and pencil. As best I could I sketched the race, a cowboy on a big stout horse in pursuit of what was admittedly a wild one. When Steve took the sketch and added a touch I thought he'd overplayed his hand for Steve put the brand on the big horse, the one that he had ridden. That Steve had stolen a horse from the rep's mount to run a wild one was perfectly obvious now. Only the rep didn't tumble. He was a good cowboy, too. By the half-light from the fire he obviously didn't look at the brand too closely and it was probably just as well.

History tells us that Cortes brought the first horses to this continent in 1519. There were eleven stallions and five mares of Arabian strain. When DeSoto was shipwrecked off the coast of Florida he had horses aboard, and Columbus brought horses on his second voyage. Many others were to follow. Cuba, San Domingo and the other islands were a great breeding ground not only for horses but other livestock as well. As early as 1700 the South-western plains were teeming with wild horses.

In his great book, "The Mustangs," J. Frank Dobie records it all. He not only tells the story of the horse on this continent but the lore and legend as well. He tells the legends of the wild stallions. There were legendary riders, too, as wild as the mustangs themselves.

I have only tried to put down what I saw and learned firsthand. To the stockmen the wild horses were always a problem. With the best blood of the range cut out, most of the wild horses had no commercial value except as fertilizer, dog and chicken feed. Every excuse was made to get rid of them. Stockmen said the wild horses ate too much grass, drank too much water.

On the Reservation dourine, a horse disease, was the excuse and they were exterminated. Over ten thousand wild horses were shot and killed on the Reservation in the early '30's. A tragic and terrifying end. Old saddle horses and pack mules from the white outfits, gone to the wild bunch, were exterminated too. The government paid so much a head for each branded animal killed. The coyotes and carrion birds never fared so well.

A friend, a horse lover, saw the last of the wild ones killed. It was at Ash Flat. For days, weeks and months the killing had gone on. There were less than a dozen in the bunch, they were ganted for water and half-starved; that they could even track was amazing. But when the hunters jumped them out that morning they came run-ning down across the big flats. Then one after another they were shot down. Underfed, undersized, in many instances their hoofs were gone. But there was nothing wrong with their hearts. Some had made their last run on bloody, spongy stumps.

To me the wild horses were as much a part of that rough and rugged land as the Apaches. Many old cowboy friends who have long since made their crossing were a part of that range, too. Its wide and rocky mesas still shimmer under the sun. Nor have its dark and brooding canyons changed, yet something has gone from the land. Nor will it ever be the same again to anyone who knew that range when the wild horses were a part of it, and they were wild and free.

Yours sincerely THE ULSTER COUNTY GAZETTE:

I was interested to note the reference in Ed Ellinger's story on Hubbell's Trading Post (August issue) to the Ulster County Gazette of January 4, 1800, preserved as a rare newspaper at the post. There is not once chance in 1,000 that the newspaper so carefully framed and cared for at Hubbell's is authentic. In fact, there is only one known authentic copy of the January 4, 1800, issue carrying the news of George Washington's death. It is filed in the Library of Congress.

But there are literally thousands of counterfeits. There are two, at least, right here in Santa Paula. And in many other communities I have come across them carefully preserved as a rare historic newspaper-in attics, trunks, and framed upon the wall. Experts in the field have found, I believe, about 20 points of difference between the counterfeit and the original in the Library of Congress. The face copies, however, were printed so much like the original (by whom I do not know) that only an expert can tell them apart. This particular issue of the Ulster County Gazette, a New York publication, is one of the most famous counterfeits in publishing history-yet none of the thousands of Americans who treasure a copy seems to have ever heard of the fraud. I know it should prove of interest to Mrs. Roman Hubbell, Don Lorenzo's daughter-in-law.

Wally Smith Santa Paula, California

BROWN-STANTON RIVER TRIP:

I have heard from a friend that the June issue of your magazine has a list of "... Important River Runs" and lists the BrownStanton party as having gone only to the lower end of Marble Canyon on the Colorado. President Brown was drowned a month after entering on the river and my father, Robert Brewster Stanton, Chief Engineer, went back to Denver, re-organized the party and with new boats went back and continued the survey to the Gulf of California, reaching Yuma on April 29, 1890.

Mrs. Lewis S. Burchard New York, New York

AT HOME OVERSEAS:

Thank you for the back issues of ARIZONA HIGHWAYS. These have been forwarded to Bonn along with the blow-ups and reprints of other magazine covers, and will assuredly be used to good advantage.

You will be interested to know that tear sheets from your publication are used by all of the Agency's offices in preparing exhibits and window displays. Many times the mounted pictures are presented to institutions, important personages, host country officials and individuals who request them. Almost invariably requests for scenic color pictures of the United States state "like ARIZONA HIGHWAYS." One such recent request, from the Agency's Lisbon office, stated that an exhibit Arizona had been prepared entirely by using pictures from ARIZONA HIGHWAYS.

Your cooperation with our exhibits program is most appreciated.

Juanita Williams Exhibits Division U. S. Information Agency Washington, D.C.

SPOTLIGHT ON WINTER

The spotlight focuses, a roving, lean And hungry moon, each ray steel-blue and cold Curtains of cloud wipe out the autumn scene, Hiding its torn and tarnished cloth of gold The amber sunset cools as night is filled With waiting silence, rustling leaves are stilled. Her ermine cloak snow-white, her step snow-light Queen of the Seasons, Winter stars tonight! -MAUDE RUBIN

MANNA

A lonely old man sprinkled crumbs on the ground, And the winter-starved birds chirped and circled around; But I knew by his smile and the tilt of his head, It wasn't the pigeons alone that he fed. -MAURINE BARCAL

A TIME WHEN

After living here for years, in the Southwest, Lines from books and readings from the skyThe love of sunshine and the yearning for rainBlur in the congealing mind to form a loose volume Of plates and impressions, footnotes and fables; Until feeling, not nimble recollection, Becomes a state of intelligence that will not again be broken down To dates and titles and first memories of sunsets, Or who came third, fourth, or fifth, tight in Spanish leather, To these wind-loose shores. A time when, closer to dying, we become What once we strove to (memorizing) learn; Men buried too deep in living to set themselves Apart from history, for having drawn it, meaning by meaning, Into the attitude-like posture of the heart. -REEVE SPENCER KELLEY

TALE OF THE OLD WEST

"He died in his boots," was the story that came. We said he was brave, and we honored his name. "He died as he danced," came a still later word. We thought him quite dashing, and gay as a bird. A man from those parts heard the tale and said, "NopeHe died as he danced at the end of a rope." -GEORGE L. KRESS

THESE AUTUMN LEAVES

These Autumn leaves that spill in golden showers And flirt and drift along my wooded path Have tongues. They speak in gentle tones which tell Of beauty of maturity and life Fulfilled; of faithful days through storm of wind And rain; of garnered hopes and happiness. But more they speak with mystic prophecy Of Spring, and greening trees and homing wings; Of Love's heart-song, and small birds in their nests In an ordered world held in the Hand of God Where birds and leaves are numbered for His use These Autumn leaves, that whisper as they fall! -LENORE MCLAUGHLIN LINK

OPPOSITE PAGE

"SUNSET OVER ROOSEVELT LAKE" BY JOSEF MUENCH. 4x5 Linhof camera; daylight Ektachrome; f.16 at ½ sec.; 5" Xenar lens; April; sunset, early evening. Roosevelt Lake, behind Roosevelt Dam, is along the Apache Trail, State Route 88. The quiet waters of the desert lake were tinted by the setting sun with the Four Peaks Mountains forming a background when the photograph was taken. BACK COVER "AN ANGRY DESERT SKY" BY KOYO LOPEZ. Rolleiflex camera; Ektachrome; f.16 at 1/50th sec.; f.3.5 Schneider Xenar lens; late August; late afternoon, camera facing sun, clouds backlit; approximately 400 meter reading; ASA rating 32. This photograph was taken east of Tucson on the Freeman Road, which borders Saguaro National Monument. Location was about a mile north of the entrance to the Monument. The photographer says: "Was wandering around in the vicinity of Saguaro National Monument, looking for subjects to photograph, when I noticed the sun was concealing itself behind an interesting cloud formation and casting dramatic rays of light that radiated out from behind the cloud. I hunted frantically for a suitable cactus with which to frame the picture, and had just time enough to take a meter reading and make several exposures before the sun emerged below the clouds. The picture was taken looking west at about an hour or more before sunset. I think the picture is especially interesting because of its monochromatic blue color. It proves that a sunset doesn't have to be red to be interesting."

Already a member? Login ».