VALLEY OF THE SAN PEDRO

Following A Moody River Through A Moody Land The SAN PEDRO VALLEY COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY BY JEFFERY J. KURTZEMAN

A thousand years ago a traveler topping out on the heights that form the western boundary of the San Pedro River Valley must have been moved by the sight of the color and depth and distance lying before him.

Four hundred years ago Melchoir Diaz, the first horseman ever to make tracks in this wide semi-desert stretch of southern Arizona as he vanguarded for the Coronado Expedition, must have been struck by the immense views of the wonderful, yet formidable, valley with its abundance of water and trees in the narrow confines of the long river bottom, and its deeply broken, abruptly rising desert mesas and ridges leading steadily up on both sides to the rough and lofty pinnacles that hem the entire length of the river now called the San Pedro, and known at that time on the crude early maps as the "Nexpa."

Today the sight of this immense panorama, looking almost the same as it did in 1540, leaves the viewer charged with wonder. A thousand years from now it will still do so. So rough are these ridges and deep gulches, so towering these colorful sparsely-timbered mountains, it is likely the country, in spite of local affluence and highway development to come, will forever remain wild impassive prominences and depressions upon which the sun and clouds paint changing pictures.

I had my first view of the valley from the old Mt. Lemmon Highway about three miles southeast of Oracle where the oaks and granite dells give way to the sunparched slopes that drop two thousand feet to the river which from there is a faint dark green line seen between the knobby ridges made by deep gullies that millions of summer storms have cut into the diluvium, the sedimentary deposits left when the inland seas that once covered much of the Southwest dried up.

On Ray Spring Hill, which was to become very familiar to me in the next 21 years, there seemed always to be a little wind in the palmillas and manzanitas. Right from the start I was impressed by the dominant color scheme of the Southwest yellow (the dry grasses and weeds) and violet (the mystically colored rough mountains which extend unbroken, and impass-able to wheels, longer than any range I have ever seen). The look of distance is deceptive. The average width of the whole valley, from the Sonora Border to the Gila River, is between 20 and 30 miles.

Its length is approximately 125 miles, and my first sight took in most of it from the faint blue Winchesters and Little Dragoons up near Benson to the Gila River which is back-dropped by the Dripping-Springs Range and the far heights of the forested Pinals. To the east, Mt. Graham near Safford looms above the 5,000 to 7,500 feet of the Galiuros. And to the northeast Stanley Butte, near San Carlos Lake, rises dominantly.

My first look was in the fall of 1930. There was then no sign of human occupation in all the panorama except the crude two ruts of the rocky road leading to the San Pedro River. This old road was traveled by the stages to Florence back in the 70s and 80s. And the 13 miles of it from the old Mt. Lemmon Highway down to the bottom land was maintained, by and for the users, with pick and shovel even in my time; fortunately I had a companion on my first trip. When we crossed the river at Sacaton Ranch and started through the thick mesquite montes along the shelving level land on the east side, we found that recent rains had cut the sides of all the little gullies and big washes and deep canyons all the way to our destination: Redington School at Carlink Ranch. It took two hours to make the 14 miles.

Today the view from my highpoint includes much of the 500-foot smokestack at the San Manuel smelter, and the head frames over the shafts at the Magma Copper Co. mines at Red Hill west of Mammoth. These are, nearly 40 years later, the only visible signs of civilization. The bare-faced canyon-creased Galiuros still steal the scene. (The engineers and surveyors who come out from universities and rely on maps say it in four syllables: Ga-li-ú-ro. We who live on the San Pedro say Galuro. I have some prospector friends who speak of these wild lonely mountains as "The Glories.") Fortunately the Spanish explorers, under leadership of educated missionaries, liked to name natural wonders for the saint on whose day each was discovered. So our splendid mountains that rise nearly 9,000 feet on the western rim of our valley are the Santa Catalinas. From our side this range is not the huge bare stage-backdrop picked-up-and-plunked-down on the desert which is seen from Tucson. Rising steadily on rocky slopes and steep ridges, they are gradually contoured into pleasing curves. And they are forested. Their blue peaks, seen from my west windows, are arranged as if by a scene director.

The most magnificent scenery in the length of the northsouth valley is seen from the fine new Highway 77 coming down from Oracle at the northern tip of the Santa Catalinas to Mammoth and San Manuel. There the mountains on each side stand highest. As with all southwestern ranges they are at their best at certain early and late hours of the day and under special weather conditions when light and shadows give illusions of unearthliness.

Visitors to the rugged country where I live cry: "It is beautiful!" No. To me, beauty of landscape must have great trees, sparkling water, and green grass or fields. This wild, dry, pitiless valley I have come to love is not beautiful. It is picturesque. Spectacular. These rough pinnacles and escarpments and metallic chimneys are at their best near sundown when the slanting light rays brighten them with luminous glow. This is enhanced if there are cumulus clouds to splash the intervening depressions with purple or dark blue shadows. I live on the wrong side of the valley to get the daily view of this eveningsplendor. But every morning I can look across the miles of westerly space and get the radiance on the blue Catalinas. When there is a red sunrise in a time of winter storms I sometimes see from the small window of my shack the blue celestial peaks capped with pink snow.

In late afternoon I like to stand in the wide green fields that border the river, especially if there are white-face cattle cropping the tender green, and see the giant cottonwoods along the field edges, the mesquite jungles across the sandy river bed, "Río Santa Cruz," and he has maps to prove it. He says the Spaniards and Mexicans often have several names for the same river. Of this one he says: "It was known as San Felipe Gracia Real de Guévavi de Terrenate, San Bernando Gracia Real de Terrenate, San Pedro de Gracia Real de Guévavi de Terrenate, Santa Cruz de Terrenate, San Felipe Gracia Real, and possibly in other ways which have not survived." Early writers have given different names to the San Pedro River. In his diary Father Kino referred to it as "Río San José." In 1850 Col. Graham called it "Río Puerco" probably because he encountered it in flood. Lt.-Col. Cooke, 1846, wrote of it as "The José-Pedro River." The historian Coues thinks its present name derived from Casas de San Pedro just over the border in Mexico, as shown on boundary survey maps drawn up in 1853.

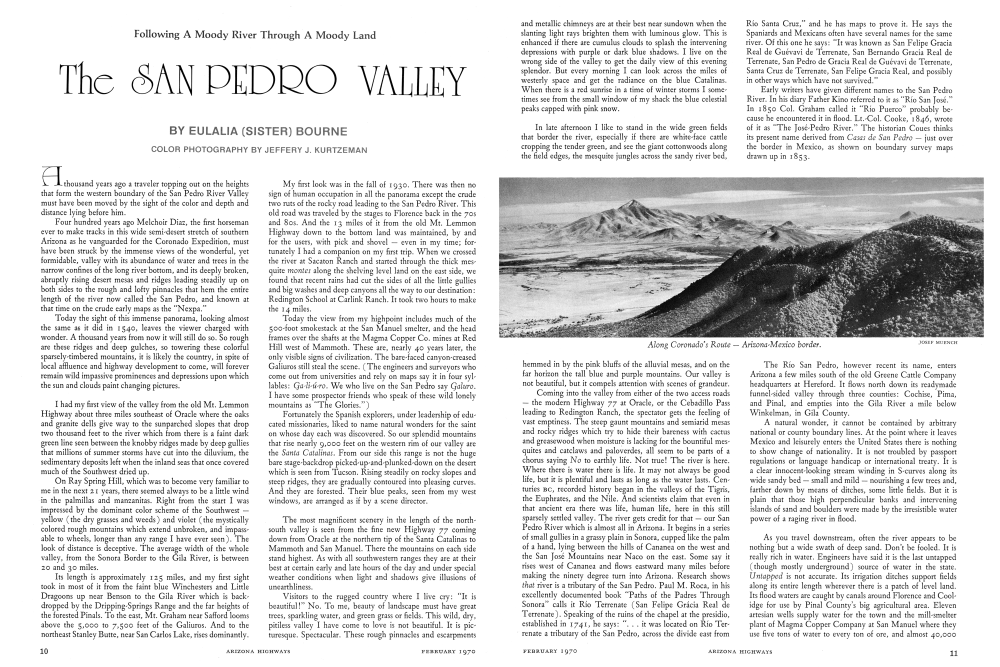

Hemmed in by the pink bluffs of the alluvial mesas, and on the far horizon the tall blue and purple mountains. Our valley is not beautiful, but it compels attention with scenes of grandeur. Coming into the valley from either of the two access roads - the modern Highway 77 at Oracle, or the Cebadillo Pass leading to Redington Ranch, the spectator gets the feeling of vast emptiness. The steep gaunt mountains and semiarid mesas and rocky ridges which try to hide their bareness with cactus and greasewood when moisture is lacking for the bountiful mesquites and catclaws and paloverdes, all seem to be parts of a chorus saying No to earthly life. Not true! The river is here. Where there is water there is life. It may not always be good life, but it is plentiful and lasts as long as the water lasts. Centuries BC, recorded history began in the valleys of the Tigris, the Euphrates, and the Nile. And scientists claim that even in that ancient era there was life, human life, here in this still sparsely settled valley. The river gets credit for that our San Pedro River which is almost all in Arizona. It begins in a series of small gullies in a grassy plain in Sonora, cupped like the palm of a hand, lying between the hills of Cananca on the west and the San José Mountains near Naco on the east. Some say it rises west of Cananea and flows eastward many miles before making the ninety degree turn into Arizona. Research shows that river is a tributary of the San Pedro. Paul M. Roca, in his excellently documented book "Paths of the Padres Through Sonora calls it Río Terrenate (San Felipe Grácia Real de Terrenate). Speaking of the ruins of the chapel at the presidio, established in 1741, he says: ". . it was located on Río Terrenate a tributary of the San Pedro, across the divide east fromThe Río San Pedro, however recent its name, enters Arizona a few miles south of the old Greene Cattle Company headquarters at Hereford. It flows north down its readymade funnel-sided valley through three counties: Cochise, Pima, and Pinal, and empties into the Gila River a mile below Winkelman, in Gila County. A natural wonder, it cannot be contained by arbitrary national or county boundary lines. At the point where it leaves Mexico and leisurely enters the United States there is nothing to show change of nationality. It is not troubled by passport regulations or language handicap or international treaty. It is a clear innocent-looking stream winding in S-curves along its wide sandy bed - small and mildnourishing a few trees and, farther down by means of ditches, some little fields. But it is plain that those high perpendicular banks and intervening islands of sand and boulders were made by the irresistible water power of a raging river in flood.

As you travel downstream, often the river appears to be nothing but a wide swath of deep sand. Don't be fooled. It is really rich in water. Engineers have said it is the last untapped (though mostly underground) source of water in the state. Untapped is not accurate. Its irrigation ditches support fields along its entire length wherever there is a patch of level land. Its flood waters are caught by canals around Florence and Coolidge for use by Pinal County's big agricultural area. Eleven artesian wells supply water for the town and the mill-smelter plant of Magma Copper Company at San Manuel where they use five tons of water to every ton of ore, and almost 40,000Tons of ore a day are processed. The oldest artesian well (at the Hundred-Eleven Ranch) has been flowing day and night for more than 70 years. The artesian wells at St. David, near Benson, have been supplying a farming community since early in the 80s.

In 1540 when Captain Diaz startled the natives with his fifteen armored horsemen, he found small irrigated fields of maiz, frijol, and calabaza along the river. He reported no thriving communities among the peaceful Sobaípuris only poor villages of 20 or 30 huts whose people grew only subsistence products which they no doubt shared with the raiding Apaches. He was looking for gold. It took three more centuries to convince travelers and homeseekers that for life's sake water is more precious than gold. And almost as inequitably distributed.

If you've never seen Southwestern rivers in flood it would be hard to imagine the incredible quantities of mudstained water laced with crashing boulders and even huge trees, roots and all that come roaring down between banks and out-of-banks each rainy season that lives up to its name. If all this water could be caught and spread out equably over the land the Great American Desert would be for better or worse, a jungle.

Since prosperous Tombstone days there has been talk of a dam on the river near Charleston. My neighbor Joyce Adams Mercer told me, laughing, "I wrote a theme on the Charleston Dam when I was a senior in Benson High School!" She now has a grandson in the University.

Recent newspaper accounts say that this dam is to be a part of the Central Arizona Project. Some of us on the San Pedro wonder about that. There are rumors that the water will be taken over the mountains to Tucson.

Looking at the big installations at Ft. Huachuca I asked if they got their water from the river.

"No," an engineer told me. "It comes out of the Huachuca Mountains. And Sierra Vista gets its water from 600-feet wells."

"But that's San Pedro water," I insisted, staring down at the river four or five miles below. "It would drain on down to replenish the water level there!"

Several years ago the moving picture "Red River" was made on the upper San Pedro River. They scraped dirt and sand to make a big temporary dam to hold back enough water to swim their herds across as the story demanded. The deep gently flowing clear water, the great trees, and the mass of swimming cattle made a wonderful picture. Our river should look like that all the time if our climate could be free of the Long Dry Spells.

The February 1945 issue of Arizona Highways featured a nice picture of the San Pedro by Stan Adler of Brewery Gulch Gazette, under which he wrote: "Men have drowned in it, men have bathed in it, and men have blistered their cowboy boots trekking across it during a drought. There are stretches of veteran willows and cottonwoods, of sage and sand, of eroded walls dotted with owls' nests, of gravel flats At points the river is a frail ribbon of water, at others it is a wide but shallow expanse. Except for short periods after heavy rains, it can be crossed on horseback at almost any point without wetting the pony's belly In the country of 'big water' the San Pedro may not cut much of a swath as an aquatic phenomenon. But the natives of the San Pedro Valley consider it's their river and they'll stick to it. If you hooraw them about it and ask what the San Pedro has got that other rivers haven't got, they will tell you with justifiable pride: It runs north!'"

In the area where I know it best, from Redington down past Mammoth, I call it my river. "My old dirty river," I say affectionately, reveling in its smell of dampness and salt cedars and batamotes; dismayed by its lavish way of slopping its viable waters to all unpleasant and obnoxious plants ruining poor farmers' fields with foxtail, sunflowers, cockleburs, and mean stickery weeds like Russian thistles that lacerate an old cow's mouth when she bites into a flake of river hay; deploring the terrific yearly damage of its mighty floods. But always enjoying it and respecting it, and often afraid of it. Those Redington years when I went home to Tucson each weekend, I had to drive fifty miles on Sunday nights before I got to the river to see if I could cross it or not. Many times I took off my boots and waded across the water at the rocky crossing to test its depth, then tied up the fan of my Model A and dashed across holding my breath, for there was no help within fourteen miles.

My river has made history. And still does. And it has made geography, also. How many millions of tons of soil and sand from this valley have I seen roll down it to the Gila River and on to the Gulf of California? At least eight people and countless cattle and other animals have lost their lives in it since I have lived within its environs. How many teams and wagons and, in later times, automobiles have washed away when their hapless owners took a chance and drove into it? How many times have I had my own vehicle sunk to the housing in the churnedup sand after a rise has obliterated the road crossing? Now that I am less able to dig and jack the car up on flat rocks, and break off brush to pave the bottomless sand, I never enter it until others have packed down the ruts. I go miles around to come to a bridge the one below Mammoth, or the old one at Benson. It is not always easy to know when the sand is navigable or when a new flood will strike. My neighbor Hugh(Shorty) Neal, hauling hay across the river, got stuck in the wide crossing at the Old Muleshoe Ranch now abandoned. Suddenly, as he dug beneath the wheels, a wall of water from a storm up the river hours before, roared down and carried away his load of hay and half-buried his truck. Getting out with his life, he walked to the Hundred-Eleven Ranch and borrowed a tractor to pull out his truck, but it was never any good after that.When the Magma Copper Company began operations here in the 50s there was much new activity and many new residents, one of whom was a bartender at Oracle Inn with a talent for friendly entertainment. People flocked in to hear his hearty greeting and see him juggle ice cubes. A young man new to the country and to the cattle-raising industry invited him to go on an inspection trip to his new ranch just across the river from Mammoth. He had a big new car. The two men, both over six feet tall, arrived at the San Pedro to find it running a hundred feet wide, but it did not look very deep. "Can we cross that?" asked the bartender who later regaled his customers with the story. "There's one way to find out," said the new rancher. In they drove. And out they jumped when the dirty water poured in on them through the windows. In Mammoth they got a wrecker to pull the car ashore. Said the jolly bartender: "It just cost $500 to find out we couldn't cross the river." As with many Arizona streams, it is more river than it looks; although, as the Indians say, it is often "upside down," hiding its water under many feet of overburden. There'll be a mile or two of wide dry sand dotted with thick clumps of river bushes easy for cattle to hide in, hard for horsemen to ride in. But go on upriver (or downriver) and before long you will come to places where permanent water ripples over the bedrock. Countless numbers of wildlife as well as domestic livestock share these living waters. And every year many of them, loitering in the shade, are caught by quick floods and swept away.Many rivers form their own winding passways, inexorably, and seemingly, in cases, impossibly, cutting through hill and plain on their journey to ocean nirvanas. This one did not. It found its "way" ready made. In this section of Basin and Range geological formation, chains of mountains on both sides arose, by underground power, lifting their natural buttresses to slanting positions, leaving a wide gutter where the river, with its many washes and canyons cutting in from both sides, could easily slash through the diluvium to make a relatively straight course from its 4275-foot elevation where it enters Arizona to the 1923-foot-high confluence with the Gila, the mighty river which Edwin Corle says "has a history as long, as dramatic, and as significant as any in America."Its channel has not changed much, except to grow wider by flood action in the Lower Valley; but the river has changed. A hundred years ago it was fouled in low areas by swamps. The soldiers at Old Camp Grant suffered more casualties from malaria than from Apaches. At St. David and Babocomari settlers were plagued by disease-bearing mosquitoes and squashy bogs. On the afternoon of May 3, 1887 there occurred in the Tombstone-Charleston area a thing unheard of before or since in this valley: a local earthquake. It seemed to center on the river. A reporter from The Tombstone Prospector wrote that it lasted the first shock 35 seconds. He said that several women and girls fainted, much plaster was knocked down, the north wall of Schiefflin Hall was badly cracked, bottles were thrown off shelves, every clock in town was stopped, and "our citizens were very badly scared."

The most significant result went unnoticed for some time. The earthquake marked the end of the swamps on the Upper San Pedro. Artesian wells broke to the surface, and in St. David they are still producing and there is no trace of the malaria that plagued the early Mormon colony there.

About the same time along the river's lower banks, near the Gila, the settlers' plows and the heavy floods helped to give the ubiquitous mesquites a chance to take over and send stagnant moisture skyward by way of jungles of branches, leaves, vines, and bushes now called "the montes." So ended the malaria hazard.

The San Pedro Valley, like all Gaul, is divided into three parts: the Upper San Pedro Valley, the Lower San Pedro Valley, and Benson.

Benson is the divider, the four-way intersection opening to destinations in all directions. The town calls itself "The Gateway to the Land of Cochise." It is gateway to much more. The south "gate" leads, by modern Highway 90, to Ft. Huachuca, long a border military post and now a booming national defense base of great importance; and to Sierra Vista, the Fort's pretty little civilian town on the slope toward the river; and, on branch county roads, to the tourist sites of Old Charleston and Fairbank well worth the trip to history buffs; and on south to the Coronado National Memorial where some claim Fray Marcos de Niza entered what is now Arizona in 1539. Also south, but east of the San Pedro, via Highway 80, to famous tough old Tombstone where a gallant corps of townspeople are devoted to keeping the past alive, and on to the Land of Cochise and the interesting town of Bisbee built on canyon walls in a rich gulch of copper; and to the border town of Douglas and its twin city on the Sonora side of the line: Agua Prieta.

Historic Tombstone always rewards the visitor with sites and relics which once made the San Pedro Valley a land of major historical significance in days of Westward Ho. Left: County Courthouse - a fine example of Territorial architecture. Now a National Historic Landmark. Below: Fly's Photographic Gallery (restored) and adjoining the site of the shootout at the O.K. Corral. Lower: Office of the Arizona Territory's most famous newspaper, and still in operation.

Benson's north "gate" has little to offer in the way of roads. What it does have is a bridge. This saves the people of Pomerene and the farmers and ranchers downriver around Cascabel and Redington from isolation during the southwestern monsoon season. When I taught at Redington in the 30s it was only 22 miles to my homestead on Pepper Sauce Canyon. But when the river was up I had to drive all around the Catalina-Rincon Mountains by way of Oracle, Tucson, and Benson a distance of 150 miles. One Sunday after unusually heavy rains it took me four hours to shovel my way the 48 miles from Benson to Redington. The San Pedro River has many tributaries, some of them miles long, and all do their best to help whisk away the water and soil that might keep the country from being a desert. The oil companies do not change the road maps they give to traveling customers. Once a dot is down on the map it is there to stay. Cascabel is such a dot. Motorists wanting to see the "out back" won't find it. Old-timers can tell its colorful past. Alex Herron had a ranch and store there and maintained a post office on the Redington Star Route for 20 years. He wanted to call his post office "Pool" in honor of his neighbor by that name who was giving up his ranch post office. The Washington authorities said he must submit a name that had never been used before. Pondering this, he met a Mexican who had just killed a large rattlesnake by the roadside. He asked him what it was in Spanish. "Vívora de cascabel," answered the man. That gave Mr. Herron a name for his post office. Now Cascabel is that dreariest of decaying buildings an abandoned school. As for Benson's East and West "gates," the once glamorous Southern Pacific Railroad and the coast-to-coast national Highway 80 hit Benson smack down the middle of its main street. From the beginning of American westward travel the town had three natural advantages: the Dragoon pass on the east allowing traffic to get through the massive mountain ranges; the wide pass to the west between the tall Rincon Mountains and the rough Whetstones; and, best of all, the river, lush with water so indispensable to travelers and settlers.

Benson was named, in 1880 when the Southern Pacific Railroad came through, for Judge William B. Benson of California who was a close friend of Charles Crooker, president of the railroad, and was given no argument by the authorities regarding his choice of a name for his post office. For thirty years before that, the spot had been an important station on the overland route to California. The Butterfield stage maintained a stop there called Ohnesorgen (German for something like "without care," probably giving a feeling of security to the wearied and worried stage riders). The station had thick adobe walls with portholes for guns, and usually eight soldiers were stationed there a hundred years ago. At the time there was a toll bridge across the river. This bridge, as well as the old station, all washed away in the big flood of 1883. The railroad bridge survived (until another great flood about 1926 when it was replaced with a duplicate which stands today). And for more than fifty years Benson knew the happy bustle of a booming railroad town.

My friend George Kempf was born there in the nineties and has lived his entire life there. He remembers the shallow tree-shaded river where boys could wade and catch minnows, and go downstream to a waterfall cut in the clay at the foot of which was a deep pool for swimming. Gradually the floods washed the clay falls upstream until now the river bed is ten to twenty feet lower than the town surface and has dangerously straight-sided banks . . . nostalgically George remembers the trains. They were many and all stopped at Benson. The little depot with its garish yellow and red paint and its furiously clicking telegraph keys and visor-capped station-master was the life of the town. Everybody around had some vital interest in the railroad and nearly everybody met all the daytime trains. George's father had a bakery and took fresh loaves of good German bread to sell to the dining cars and the cabooses, daytime or nighttime.

I was a young visitor to Benson in 1912 for one summer. I remember the fascination of being close to trains. By day most of them came from the west. You could smell the smoke (rich, pungent coal smoke) and hear the clanging bells and the hissing steam and the long, lonesome wail of the steam whistles four times for a crossing and feel the vibrations of the clacking wheels. We counted the bright-colored box cars and tried to read their legends and guess at their contents. And ran out in the evening with buckets to pick up chunks of coal for the cookstove. At night we slept out in the yard. There was the brilliant sweep of the great headlight, the noise and smoke and inimitable wail that woke the echoes of empty spaces of mountain and plain and river bottom. Pulling up the long, steep grade going east, the trains had trouble. There were always spare locomotives standing by to couple on and help the main engine through the pass the highest point between Los An-geles and El Paso, and, I believe, all the way to New Orleans.

Halfway up to the Pass, even with the extra locomotives, the freights had to stop at Ochoa Station to take on water. The fifteen mile climb was so steep that there was a switchback on the line called “The Horseshoe Bend.” Dave Adams, rancher from Texas Canyon, father of my friend and neighbor Joyce Adams Mercer, had a pipeline from his ranch the several miles to Ochoa to supply water for the railroad tank. As a child she sometimes went with him as he rode the line checking for leaks and airlocks. He loved the railroad (as all in the country did) and was bitter when the town voted not to accept the roundhouse. They said it would bring in dirt and a tough element. So it was installed at Tucson.

In the old days Benson, besides its importance to the Southern Pacific, was the terminal of two other trunk lines: the Arizona-Mexico Southern Pacific, south through Fairbank, and the El Paso and Southwestern coming west by way of Douglas. It was the young metropolis of southwestern Arizona.

Today Benson is encircled by growing housing developments; the population, steadily increasing, is the biggest in its history. Why? The pleasant climate, the wonderful scenery, and the accessibility of the remarkable Interstate 10 expressway to Tucson, have attracted new residents and modern split-level homes with patios and swimming pools and landscaping up on the hills above the old town.

Carl E. Winter, editor of the Lower San Pedro weekly The San Manuel Miner, stood out on his porch with a visiting editor who, impressed with the view, remarked: “It would be interesting to know the history of this valley.”

“Storm Over Cananea”

It would not be difficult to learn the little amount of its recorded history. The unrecorded history staggers the imagination. Edwin Corle in his book “The Gila River of the Southwest” (of which the San Pedro is the chief tributary from the south) estimates this part of the earth as being 60,000,000 years old. He may be off a year or two, but surely our country is very old indeed. All along the bottom lands where the river has cut into the mesas and promontories of the diluvium prehistoric evidences are visible. In the First-Mile-Wash on the road to my canyon the layer-cake old age marks show the slow decline of the inland seas that once covered much of our state. At points erosion has carved great castles and precipices in the pink clay and these add color to the view the traveler gets as he comes down from Oracle on Highway 77. Upriver on the east side there are dykes and cliffs of white diatomaceous earth chalky material left from shells of ancient sealife. Mr. Corle claims, too, that the land from 15,000 years ago down to modern times has changed very little. He says: “When Babylon fell, when Christ was born, when the Battle of Hastings was fought, when the Crusades were launched . . . the Arizona desert [and valleys] supported a race of people who can be described in no other way than civilized.” The geologist James G. Bennett claims to have found artifacts around Willcox (over the hills from the San Pedro) that are ten to fifteen thousand years old and give him reason to believe that man has lived in this area longer than in most places on earth. If man did he wrote no history.

The first people who did were the Spaniards who came up from New Spain into Pimeria Alta long before the Pilgrims landed. It is well known that the first European to tread the sands of the San Pedro was a black man, Estevan de Dorante, who was sent ahead by Fray Marcos de Niza, who gets credit from many historians for the “discovery” of Arizona in 1539. His report triggered the expedition of Francisco Vasquez de Coronado in 1540 whose object was to find the Seven Cities of Gold Cibola. Explorations were made and the official historian Pedro de Casteñeda made reports. Yet, except for two brief visits from the Southwest's greatest hero, Fr. Francisco Eusebio Kino, in the late 17th century, no settlements by white people were made in this fertile well-watered valley for more than 300 years. The reason is spelled in six letters: ÁPACHE.

These bold antagonistic people occupied as their strongholds some of the roughest, most inaccessible country on this continent the mountains east of the San Pedro and south of the Gila. Their war against the white man is said to be the second longest on record. A Texas historian claims that the Comanches, who defended their lands and tribes against the white man for more than four hundred years, fought the longest defense in all history. The Apaches easily rank second with their unremitting guerilla war lasting over three hundred years.

The Sobaípuris, a part of the peaceful Pima nation, occupied the San Pedro river lands on sufference and no doubt paid tribute to the Apaches. After the Spanish missions were established on the Santa Cruz River and Father Kino had made two short-lived visitas on the San Pedro in areas occupied by the friendly Sobaípuris Gaybanipitea and Quíburi, 1692-1696, according to the historian Frank C. Lockwood, a fight against the Apaches was made by brave Chief Coro who led 300 warriors. The Jocomes-Apaches offered to fight by challenging the ten best men Coro could present. The ten Apache warriors, including their leader El Capotcari, were killed and their followers routed. But this victory gained little for the Sobaípuris

Notes and Acknowledgments

For the information of interested photographers all camera work was done with the Linhof Kardan Color View Camera, on 4x5 Ektachrome Daylight Film, rated ASA 50. Only two lenses were used throughout 90mm Super Angulon, where a wide field of view was necessary, and the 150mm Symmar. A polarizing filter was used for views on pages 17, 20-21, 22 lower, 26, 29 upper right and upper left, and page 30. All exposures were bracketed at F22 and 32 at from 1/5 to 1/30th sec. A Linhof tripod was used exclusively.

Page 17 There are heavy showers over Cananea as we view from the Coronado National Memorial lookout point. The origin of the San Pedro River lies within the watershed of this broad valley.

Page 18 Hot glowing minerals on the great slag dump at the ASARCO smelter near Arizona 77 just north of Winkelman. Two exposures made. Dusk 1/5 sec. at F22, Night dumping, 6 sec. at F22.

Page 19 Late summer brings green grasses to the banks of the San Pedro containing the churning waters of the late summer runoff deep inside Mexico.

Pages 20-21 Arizona 77 bridges the San Pedro north of Mammoth.

Page 22 Upper Early morning vista from Dudleyville Corrals toward Winkelman.

Page 22 Lower Interesting land formations along Arizona 77, about 13 miles north of Winkelman.

Page 23 Upper left Crestated saguaro near Redington.

Page 23 Upper right Quiet back road about 10 miles south of Mammoth on road to Redington.

Page 23 Lower left Many swampy marsh areas still remain along the river bed.

Filming the San Pedro Valley and the area in its sphere of influence was a most rewarding experience. The variety of seasonal and geographic documentation necessitated more than a year's programming. Much of the lore and legend of the area is historical and I certainly would have been "lost in the woods" without the help of the many wonderful people who gave so willingly of their time, their recollections and provided access to records and byways.

COPPER CREEK, ARIZONΑ (ΜΑΜΜΟΤH AREA)

EULALIA "SISTER" BOURNE: A wonderfully enriching author and capable guide.

DON HAINES: A very generous individual, part-time ranch hand with Sister on the GF.

PETE CAREY: Remembering a wild jeep trip up Copper Creek to the old mansion.

MRS. JOYCE MERCER: Memories of Benson in the days of the Golden State Limited and stops at Ochoa tower to water down.

CORONADO NATIONAL MEMORIAL (PALOMINAS), ARIZONA

ERNY KUNEL: Chief ranger of the Coronado National Memorial, my favorite camera toting assistant and guide.

DARREL W. WHIPPLE: Park ranger at the memorial.

GEORGE E. BROWN: For assistance in finding the actual point where the San Pedro enters Arizona.

Page 23 Lower right A few yards downstream from where the San Pedro meets the Gila.

Page 26 Upper Typical country around St. David on the road from Benson to Tombstone.

Page 26 Lower Granite dells along the old Mt. Lemmon highway south of Oracle.

Page 27 Upper Looking north into Winkelman-Hayden along Arizona 77.

Page 27 Lower Early morning exposure of Bisbee.

Page 28 Upper left-Upper Right Prime cactus areas are near Oracle, Mammoth, Hayden and Winkelman.

Page 28 Lower The rock formations in the Texas Canyon-Dragoon area are something special.

Page 29 Upper left Storm clouds above Oracle.

Page 29 Upper right Rancho Del Rio near Hereford.

Page 29 Lower left Cattle are a familiar sight along the entire length of the river.

Page 30 UpperTaken along Arizona 92. Mule Mountain in distance.

Page 30 Lower The confluence of the Gila and the San Pedro.

Page 31 Upper left Roadway at Coronado National Memorial.

Page 31 Upper right Taken at the Amerind Foundation, one of the world's leading American and Indian archaeological museums and research centers.

Page 31 Lower left Entrance to the Old Brewery for which Brewery Gulch was named Bisbee.

Page 31 Lower right Aravaipa Creek winds through picturesque primitive country east of Mammoth.

Page 32 One comes across scenes like this at almost every San Pedro sunset time. Exposure here was F32 at 1/100 sec. A red filter was used for the effect of strong summer heat.

DRAGOON (TEXAS CANYON), ARIZONA

LLOYD ADAMS: Remembering the Ochoa tower water tank on the Adams Ranch.

DR. CHARLES DI PESO: Head of the Amerind Foundation, enriching to know, a foundation of no equal in study of Indian history.

JUAN AND ANN VON SAGE: A light on incentive, and two very gracious people.

FAIRBANK, ARIZONA

CHARLOTTE AND DUFFY of Fairbank Commercial Company, and the Fairbank Post Office, they keep the town alive.

SONORA, MEXICO

JAIME CARBALLO W.: Director of the Department of Tourism for providing a map of Sonora that the San Pedro might be traced to its origin.

In addition to the above acknowledgments, I am especially grateful to Artist Bob Eckel of Phoenix, who accompanied me on several trips to research the locales and details for the oil paintings of the Golden State Limited at the Benson station in the early 1900's, pages 24-25; and the Ochoa water tower. These were done especially for this San Pedro Valley feature, and were not photographically available.

C. S. FLY from Page 7

In addition to the above acknowledgments, I am especially grateful to Artist Bob Eckel of Phoenix, who accompanied me on several trips to research the locales and details for the oil paintings of the Golden State Limited at the Benson station in the early 1900's, pages 24-25; and the Ochoa water tower. These were done especially for this San Pedro Valley feature, and were not photographically available. To continue earning his living with a camera, a pursuit which has given more lustre to his name than it would have gained through the discovery of a good mining claim.

Whenever he could, Fly would load his equipment into a buckboard and travel about the country in the process of building up a collection of saleable pictures. Mrs. Fly, a capable photographer in her own right, officiated at the gallery.

To draw attention to his work Fly built some display cases on the porch of his home and frequently changed the showing of pictures there. The new "showings" were sometimes given notice in the newspapers and townspeople would walk down to see the new views. This Fly porch is said to have been a very popular place to sit when the weather was warm. From it there was an excellent view of the mountains.

Catastrophes needed recording as well as the beauties of nature, and when Fly learned of the devastating earthquake of July 14, 1887, in Mexico he loaded up his buckboard and headed for Bavispe, one of the places hardest hit. Some rather remarkable photographs were the result.

Feeling a just pride in his collection of photographs, the Tombstone picture-taker decided to take the show on the road. On December 7, 1887, he left on a tour of Florence, Phoenix and other points to exhibit a selection of what he considered to be the best views and portraits taken in the previous eight years.

Greeting him cordially, the Phoenix Gazette of December 31 advised their readers that, "Mr. C. S. Fly, of Tombstone, one of the greatest artists in America, arrived in Phoenix yesterday and will remain a few days . Mr. Fly obtained the only genuine pictures of Geronimo and has accumulated considerable money from their sale. The Gazette is pleased to welcome the gentleman to the Garden City and trusts that he will conclude to locate in our city. This invitation to move to Phoenix was one that Fly would take time to consider. Fly's Tombstone was not the town of crimson crime that some writers would have us believe. There was a normal family life there comparable to that in many other western towns of that period.

The popular Nellie Cashman, "whose every heartbeat throbs with sympathy with suffering humanity the world over," was one of many substantial, law-abiding citizens who helped to give the community as a whole a basic integrity. Camillus S. Fly and his wife, Mary E. (Mollie) Fly, fitted neatly into the pattern of respectability.

SAN PEDRO from Page 16

who, under Chief Coro, soon afterwards moved westward to Los Reyes near present Patagonia leaving their rancherias on the river entirely deserted. History has no more to say of the Sobaípuris. Over a hundred years of darkness closed over the San Pedro. Joseph Mack Axford, who began punching cattle for the Half-Moon Ranch just inside the Arizona-Mexico border in 1894 for ten dollars a month and "found," says the history of the Upper San Pedro would fill a big book. It has already lready filled several, one of them Mr. Axford's own "Around Western Campfires" (University of Arizona Press, 1969). There are books about Coronado whose traipse down the San Pedro left no mark on the valley unless some pigs and maybe a horse or two and a few cows strayed from the long strung out mob of followers and started herds for the natives who, up to then, had domesticated only two animals: the dog and the turkey.

And there are many books about tough old Tombstone whose shoot-outs and murders filled "Boot Hill Cemetery" which has become an attraction for tourists from all over. Even the women were tough. The Tombstone Epitaph had an account of a hair-pulling duel fought on the street in which one of the women was heard to shriek: "You quit interfering with my husband!" The rich grasslands bordering the San Pedro River on both sides of "the line" were made for cattle. When the wave of livestock that swept up from Mexico in the late 17th and early 18th centuries lapped over into the San Pedro country it was met by the barrier of the Apaches. It was in the early years of the 19th century that the land grants in this area were established. I had imagined them to be Spanish land grants like those in New Mexico and California with great haciendas in the hands of prominent aristocrats like feudal lords. No, the San Pedro holdings were Mexican land grants made after Mexico's war for independence in 1820. The San Ignacio del Babocómari Grant will serve as an example. On July 1, 1827, the treasurer-general of Santa Cruz in Sonora received a petition From Don Ignacio and Doña Eulalia Elias asking for a tract of land on Babocómari Arroyo, a tributary of the San Pedro River flowing east from the Huachucas, for the purpose of stock raising. Eight sitios were duly measured and advertised. The appraisers valued the six square leagues that contained running water at $60, and the two square leagues that were dry at $10. The expediente was concluded and the sale made in the city of Cocóspera in December, 1828, for $380. In 1851, after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, there is an account by Commissioner Bartlett saying: "This hacienda was one of the largest in Sonora. It ran 40,000 head of cattle besides large numbers of horses and mules. It was abandoned for the same reason that had caused the abandonment of so many ranches, haciendas, and villages: the Apaches." After the Gadsden Purchase, which agreed to recognize all Mexican deeds and grants, the title was confirmed by the American Court of Private Land Claims about 1880. But litigation continued until after the turn of the century when finally the Supreme Court gave clear title to E. B. Perrin who had purchased the land from the Elias heirs for $750 gold. This Babocómari Ranch was purchased by Frank C. Brophy in 1936 from the Perrins who had endured severe droughts and had given up, not being able to cope with "the elements of the heavens." Since then more land has been purchased, wells drilled, dams built, permanent pastures and orchards put into production, and excellent headquarters establised. Mrs. Cora F. Babcock wrote: "The visitor would never guess that anything but peace and serenity had ever presided on the beloved acres of San Ignacio del Babocómari.

The other San Pedro grant now forming the heart of the Boquillas Ranch owned, at the present time, by Kern Cattle Company was in two parts, both straddling the river and extending for many miles. San Raphael del Valle contained 4 sitios and was sold to Don Raphael Elias for $240 in 1820. The Camou brothers finally obtained right to this claim in 1869, 17,475 acres for which they paid $14,000. The town of Fairbank was near the center of the grant called San Juan De Las Boquillas y Nogales; the title to this land was issued In 1833 to Gonzales and Felix. In 1879 these four sitios were bought from the Felix descendants by G. H. Howard. The town of Fairbank was on the old Arizona and Mexico S. P. Railroad. In its boom days it had four stores, five saloons, three restaurants, and lots went for from ten to fifty dollars. Its citizens were relatively well behaved compared to the hotblooded neighbors of Charleston and Hereford. It had one “moment of glory” when, in 1900, Burt Alvord and Billy Stiles tried to rob the Wells-Fargo box from an express car. Jeff Milton, who had an arm shattered by bullets, threw away the key to the safe.

Mack Axford tells that during the long years the titles to these land grants were in dispute, settlers moved in as squatters, built houses, made fences for their livestock and other farm improvements. With the final decision granting title to the Boquillas Land and Cattle Company, the court issued an order to reimburse the settlers for the improvements they had made. These were appraised for value. Some squatters would not accept these evaluations and went to court in Tombstone where Allen R. English was legal advocate for the company. Mr. Axford tells an anecdote about one of these settlers he calls Frenchy. Part of his improvements was a fifty-foot pond kept filled by a nearby windmill. It was appraised at $150, but Frenchy asked for $800.

Mr. English asked: “How many days did it take you to make this pond?” “Two and a half days,” said Frenchy.

“How did you build it?”

“With two teams and Fresno scrapers.”

“How much did you have to pay for the teams?”

“Five dollars a day for teams and drivers.”

“That's a total of $25.00,” said Lawyer English. “How do you ask $800 for a pond which you admit cost you only $25 to build?” “Mr. English,” cried Frenchy, throwing up his hands. “I have $800 worth of frogs in that pond.” Quoting from Mr. Axford's “Around Western Campfires:” “This brought a roar of laughter from the courtroom as few people in those days considered frogs to be edible. However, to Frenchy this was serious, for he loved frog legs and had succeeded in selling several dozen to the Can Can Restaurant.” History has favored the San Pedro Valley with three “firsts:” the first non-Indian foot-traveler in what is now the United States (1539) Estevan and Fray Marcos de Niza); the first horsebackers to come into the Southwest (Merchoir Diaz and his caballeros, 1540); and the first wagon train to cross present day Arizona, in 1846 when Lt. Col. P. St. George Cooke led the Mormon battalion across the trackless frontier proving that wagon wheels could roll from Iowa to California.

He entered the San Pedro River bottom above the site of old Charleston and there fought the only battle of his long journey when his wagons and mounted men were attacked by a herd of wild bulls. At first they made light of the attack and thought that a few powder shots would frighten the ferocious animals. “But,” wrote Col. Cooke, “I had to direct the men to load their muskets to defend themselves.” According to Daniel Tyler, the historian of the expedition, the battle lasted for hours; the bulls were hard to kill. Horses and mules were gored, and Private Amos Cox was gored and tossed ten feet in the air. Col. Cooke wrote: “A mad bull could take two balls through the heart and lungs and still charge and gore man or beast.” There is a monument at the ruins of Charleston commemorating this strange battle.Nine years later 1853, the date of the Gadsden Purchase there was still only one east-west road across Arizona: that pioneered by Col. Cooke. In 1857 a California senator promoted $20,000 to make an improved road from El Paso to San Diego. It was known as the Leach Road (for the supt. of construction) and led down the San Pedro River more than 80 miles below Benson to the Aravaipa where it crossed the river and pulled up a sand wash to level table land “saving five days for wagons.” For protection against the Indians, Fort Aravaipa, later called Ft. Breckenridge, was established. In 1861 (a bloody date in American history) Lt. Col. Baylor with a Texas force took possession of it for the Confederacy and ordered all military stores and buildings destroyed. Knowing

SAN PEDRO from Page 37

nothing of the Civil War, the Apaches took credit for this abandonment and doubled their efforts to drive out all white men. None were left in the Lower San Pedro Valley. In May, 1862, Lt.-Col. West with four companies of California infantrymen re-established the old fort, calling it Fort Stanford for their governor. This was later changed to Camp Grant. In 1866 a great flood swept away twenty of the twenty-six adobe buildings; then a stronger camp and stockade were built up on mesa land. Attempts were made by individuals to farm the land along the river and sell the produce to the military. But the Indians killed these settlers. The post was 60 miles from a post office, so one was established there in August, 1869. Dr. Smart (camp surgeon) noted that letters reached San Francisco in twenty days and Washington in twenty-five days "unless there were delays."

The fort was moved to Sulphur Springs Valley in 1872 after the horror of the Camp Grant Massacre.

But not all Apaches were confined at the fort or on the reservation. A traveler in 1875 reported that not a single person resided in the Lower Valley. Officially the Indians had been put on the Apache Reservation.

One chief, Esquiminzin (Hackibanzin) objected so steadfastly that he and his followers were allowed to stay on their lands between the Aravaipa and the mouth of the San Pedro.

For the next few years the last twenty miles of the remote valley of the San Pedro remained empty. But, hearing of the abundant land and water, adventurous pioneers were stirred to action soon after the valley was surveyed and thrown upon for settlement in 1877-79. Scores of prospectors and homesteaders flocked in and took up claims now that they had government protection and guarantee of title.

Oracle claims the first permanent community. The Catalina foothills had always been the safest part of the country (farthest from Apacheland) and was most accessible to Tucson and Florence. Also it was blessed with an almost mile high climate, and beautiful scenery - lacking only water. O. E. Stratton, one of the early pioneers who stayed for twenty years, mining and ranching on what is now the Old Mt. Lemmon Highway, wrote: "The country was beautiful in those days. Grass was everywhere. The flat above the house (built on the site of the original dugout) was covered with sacaton (coarse bunch grass) higher than a man's head. The Strattan mesa waved with grama grass. And the flowers-poppies and Mariposa lilies, almost carpeted the ground."

Stratton was one of the first explorers to settle in the Lower Valley. During those first years when they were living in a dugout in the scenic canyon that now bears his name, his wife spent eight months without seeing another woman. This first visitor was the bride of Prof. J. C. Lemmon. Mr. Stratton, who knew the mountains well, took the bride and groom on good horses to the top of the highest peak in the Catalinas which now honors her by bearing her name: Mt. Lemmon.

Stratton, who had spent some years looking for mines, and residing in Florence where he held public office when Pinal County was organized in 1871, located his ranch at a fine spring and called it "The Pandora." It has been a successful cattle ranch from the beginning and is now called the "U Circle." His book "Pioneering in Arizona" dictated to his daughter Edith (Kitt) and published by the Arizona Pioneers' Historical Society gives graphic accounts of his many wild west experiences and his doughty neighbors and companions.

He bought ten unbroken horses, among them a very fine large gray who refused to be saddled. Every time a saddle was put on him he threw himself down and nothing would make him get up. "I turned to Manuel Verdugo and said, 'Manuel, do you think you can ride him bareback?' "Manuel was a stout, good-natured Mexican who worked for me for 12 years and was so good as a bronc rider that his friends said he could roll a cigarette while up there.

"With a little shrug Manuel answered, Yo creo que si,' and began to pull off the saddle. When the gray got to his feet Manuel was on him and rode him to a finish."

As with all Arizona frontiers, the first to come to the Lower San Pedro were the gold-seekers. And some found what they sought. Señor Castro dreamed that he was out hunting for a deer, sat down on a rock to rest, idly picked up a few stones among them a nugget. His dream came true. He sold the nugget for $80. That was the start of the Nugget Mine in Nugget Canyon, which was worked for several years. A similar story tells how the Southern Belle mine was discovered. Mrs. Young was taking lunch up the canyon to her husband who was working on a claim. On a steep decline she sat on a ledge to rest. She took out a hairpin and began scratching on the ledge. Filling her handkerchief with some of her scratchings, she hurried to show her husband. He named the mine for her: "Southern Belle." Its little mill stamped out about $300,000 in the next few years. The richest strike was that of Frank Schultz several miles down toward the river. It produced millions and sparked the town of Mammoth.

By 1880 more than 200 people lived around Oracle and in the Old Hat Mining District. A post office was established at "The American Flag" (then a mine; now a ranch). Permanent homes were built, water rights taken up and wagon roads hacked in and out of deep canyons and over perilously steep ridges.

Cattle have always been important in the San Pedro Valley. They came into the country with the Caucasians. O. E. Stratton says that a Californian, Daniel Murphey, put large herds of imported cattle Herefords, Durhams, and Devonshire stock on the lower river valley below Mammoth; but they were run on public domain and became the nucleus of various individual ranches in the area.

The fine old Carlink Ranch at Redington was established in 1875. Wm. C. Davis sold his rights to William H. Bayless of Kansas, and his son Charles H. Bayless. Later Stuart Bayless and J. W. Berkelew joined the ranch as partners. It grew, mostly by purchase of homesteader properties, to 9,000 acres of patented land and spread into four counties. It was after 1930 that the ranch began to sell certain portions of its holdings and became more compact. It is still owned and managed by Bayless descendants.

Although the Lower Valley cattle herds have always been subject to losses by meat-eating neighbors and passers-by, they never were overrun by bands of marauders and rustlers as were the Upper Valley ranches in the Tombstone area and along the Border. Squatters and homesteaders suffered along with the greater ranchers like those at Fairbank and Hereford where Mr. Axford was foreman for Col. Wm. C. Greene and Frank Moson.

No sooner had the early day raids by lawless red men been quelled than raids by lawless white men began. The Upper Valley was for a time a hangout for rustlers and robbers and killers. The editor of the Tombstone Epitaph spoke of this as "The Curse of the Cow-Boys." He printed a letter from one reader brave enough to sign it.

"Editor, Epitaph: I am not a growler or chronic grumbler, but I own stock, am a butcher, and supply my neighborhood with beef. And to do so I must keep cattle on hand. And I could do so always if I had not to divide with unknown and irresponsible partners, viz: Cow-Boys, or some other cattle thieves. Since my advent into the territory and more particularly on the San Pedro River, I have lost 50 head of cattle by cattle thieves. I am not the only sufferer from these marauders and cattle robbers within the last six months. Aside from 50 head of good beef cattle I have been robbed of, Judge Blair has lost his entire herd. P. McMinnimen has lost all his fine steers. Donbar at Tres Alamos has lost a number of head. Burton of Huachuca lost almost his entire herd In fact all engaged in the cattle business have lost heavily from cattle thieves. Horses and mules are gobbled up by these robbers. Is there no way to stop this wholesale stealing of stock in this vicinity or in the county? -T. W. Ayles, Cattle Dealer, 3-18-1881. At that time ranchers were not the only ones to suffer from outlaws. Stages were robbed, trains held up, and there were 25 killings within two years. Territorial Governor John J. Gosper wrote to Washington about the "Cow-Boy Scourge,"and the attention of Congress was called to it. In May, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur issued a proclamation threatening to send the militia into Arizona to restore and maintain law and order. Whether it was the president's threat, or the fact that the Earps had "riddled the ranks" of the banditry leaders, or that "the bad men went out with the Earps," at last peace came to the Upper San Pedro Valley.

For at least 25 years goats took over the Dripping Springs country and the adjacent areas along the Gila and the lower regions of the San Pedro. Dillard Shartzer, near the mouth of the Aravaipa, had the biggest goat ranch in Arizona. He ran seven herds 14,000 goats. The Whites and the Woods, residents of the Aravaipa for three generations, had goats to beginwith, although they long ago became established cattle ranchers, and maintain the beauty spots of the canyon. Fred and Cliff Wood have made a paradise of their "Panorama Ranch" with its wonderful fruit trees and green lawns and bright flowers. The time to visit there is when the orange blossoms are pervading the atmosphere along the clear sparkling streams and ditches of mountain waters with their inimitable fragrance.

The goats were sheared twice a year and shipping days were high old times for Winkelman, where there was a bar almost every other corner.

As it did for practically everything, the Depression ruined the market for mohair and put an end to the thriving goat business. The cows, although they went down to $12 a head, came back to the Valley of the San Pedro. But the land that is the vegetation never fully recovered.

Old-timers look at the thick chollales and the burro weed in the Lower Valley and the sage and unmanageable non-productive scrub mesquite in the Upper Valley and say: "It wasn't like that in the old days."

Dr. Charles Di Peso, of the Amerind Foundation, an authority on Indian tribes of the Southwest, speaks of the five life zones of the San Pedro from the lower levels (2,000 to 3,500 feet) with cactus fruit, agave, mesquite beans, on up through acorn-bearing oaks thick with small animals, and piñones and berries, up into the pines with deer and turkey and, at highest (9,000 feet) elevations, bears and mountain sheep.

Certainly elevation merges with rainfall to control the vegetation. From a browse standpoint, the best growth is found on the mesas and ridges between 3,000 and 4,500 feet the abundant and fruitful paloverdes, mesquites, and catclaws. To be impressed with the natural beauty of our river valley, come in April-May when the lovely wild flowers and paloverdes are blooming. The most prized plant of the desert country is the paloverde (literally stick of green). These thrifty trees (they do not easily starve for water) after a good spring cover themselves with shining yellow blossoms. Spanish-speaking people call them “showers of gold.” And they are just that. Seen against the green of the mesquites with the pink clay banks and purple mountains in the background they are beautiful.

Also, it is safe to call this the Land of the Saguaro. From Redington all the way down to the Gila River the Lower San Pedro Valley has more and better saguaros than, I venture to say, any place on earth. All the rocky mesas and the south slopes of every ridge are thick with them. A traveler along the highway, or country road, can see many fine specimens close at hand; and he has only to look across the river and behold them by the thousand. Each one is different (some are downright freaks) and all make fine additions to the scenery. Their fruit, ripe in July, tastes something like ripe figs. The Indians made good use of it and the birds are crazy about it.

The scenic gem of this wide area is the Aravaipa, the longest, best-known, and most photogenic tributary of the San Pedro. Like Oak Creek Canyon, the jewel of the Verde Valley, it has the first requirement for landscape beauty a stream of clear gushing water. It does not have the massive red buttes and the roomy variety of Oak Creek. It does have high, steep bluffs in beige, pink, off-white, and red-orange rising above the great green trees for which the canyon is famous. The land is privately owned but every Sunday and holiday picnickers arrive hunting the cool shade and inviting water. Happily the Apache name has survived. It is said to mean Running Water or Laughing Water and that's what it is.

For so serene an Eden it has a bloody history. Besides the massacre of the Indians it has been the scene of several gun killings and present residents will show you where X marks the spot. The old range-war boys and determined squatters meant business. All is peaceful now. The all-weather road (for the school bus) winds quietly and sometimes abruptly in and out of the hillsides above the green trees and sparkling water.

Not so in the old days. One summer in the twenties I visited the Buzan girls at their “Trail’s End Ranch” which was as far up as vehicles could go. It was a hazardous journey for the little cars having to cross the deep water twenty-two times. Some never made it and were lost in the floods.

That was the time of the fruit ranches. Each morning of my visit I climbed up in a 40-foot tree and feasted on luscious figs. They were too high and too many to do much with. One tree on the Brandenberg Ranch was claimed to be the biggest fig tree in the world - 60 feet high.

Moonlight nights we bathed in the waist-deep rushing water and sat outside (mosquitoes to the contrary) and filled the fragrant air with songs, after strenuous days of scratches and chiggers, picking berries for jams and jellies and making the most delicious cobblers out of tree-ripened peaches.

But fruit ranching was never prosperous. The transportation problem was too great. The Buzans sold their ranch to a wealthy easterner who sent in heavy equipment and scraped out the trees and put in permanent pastures for blooded horses and pure-bred cattle. Fine houses and barns were built and a good road promoted. But nostalgically I remember the great trees growing along the ditches. And fruit unsurpassed!

The remoteness of this valley has been caused mainly by lack of roads. It is still the only section of Arizona of comparable size that has no state highway through it. That is now being taken care of. There are ultra-modern four-laners near the beginning and the end of our river; and at last construction is being started on the middle area between Benson and San Manuel. Already incredible to us old-timers for so many years isolated during rainy seasons a bridge now at Redington!

able size that has no state highway through it. That is now being taken care of. There are ultra-modern four-laners near the beginning and the end of our river; and at last construction is being started on the middle area between Benson and San Manuel. Already incredible to us old-timers for so many years isolated during rainy seasons a bridge now at Redington!

I look across the once clear-aired valley to the great mountains now dimly seen through smelter smoke. Oh, I'm glad to see that smoke! It means new shoes for all the babies, and good schools for our young citizens. But during the long strike, how beautiful the world was!

It took fortitude to be among the first settlers. In the fierce heat of arid southwestern summers there was no ice. There was little protection against crawling and flying insects and dangerous reptiles and wild animals. The valley was rich in wood. People could keep warm in the cold of river and mountain winters if they stayed indoors. Traveling was hazardous and never comfortable.

Even the women were rough in a country that stayed rough for half a century. I remember some. There was “Two-Gun Sal” - the only name I ever heard for her. She was a square-built ruddy-faced blonde of uncertain age with a loud voice. Bill Wilson, a cowboy visiting at my homestead, came in one night cracked up with laughter. He had sat by “Two-Gun” and listened to her stories of Table Mountain, and finally mentioned that he would like to see the place.

“Why you poor little son of a,” she roared, “you couldn't even stay alive on Table Mountain!”

Many of the first-comers in the post-Apache days not finding gold hunting or cattle raising on public domain profitable, did not stay to become permanent residents. However, they usually left something of themselves, if only their names, to the valley. We have Redfield Canyon, Peck Basin, Davis Mesa, Geesaman Canyon, Soza Wash, The Markham, Putnam Canyon, James Gust Wash, Zapata Arroyo, and Charlie Dyke. How I hated the Charlie Dyke, the most perilous wash I had to cross on my way (before there was a real road) to Redington. It had high clay banks, at least six feet at the crossing. Every flood sliced them perpendicularly so that woeful digging fell to the first to cross Charlie Dyke.Much of Copper Creek mining has turned out that way, also. Copper Creek is the second longest tributary of the San Pedro and its rocky uphill road is most traveled of all the back country roads in the valley. It has a history of mining activity dating from 1863. At one time it was called “Gold Hill.” During the 30s, while producing over three million dollars worth Westward Ho was sparked by man's search for gold, and this extended into the San Pedro Valley from the time of Coronado. In the Upper Valley fortune hunters and subsequent population had the lure of Tombstone's silver. In the Lower Valley gold was found as well as silver and, much later, copper and molybdenum. Around Oracle half a million dollars was taken out before the end of the century. The Apache Mine (sometimes called the Control Mine) was bought by a Boston Company for $20,000 in 1881. Mr. Stratton owned adjoining claims which he called The Comanche. He bonded them to a Tucson man (Edward Reilly) for $600. One snowy afternoon The Apache Company looked him up and offered him $20,000 for his claims. He caught up a good horse and at five o'clock the next morning was at Reilly's door, having endured a wild, cold, all-night ride over a great trailless mountain range. “No, no,” said Reilly. “Sit tight and we'll all be rich.” That was the end of the story.

Of molybdenum, it had a population of nearly two thousand which is hard to believe. The steep-sided canyon is so narrow that in most places the creek barely leaves room for a one-way road carved out of its high south banks. People lived in tunnels and in shacks jammed together on every flat place, even climbing hillsides so one hut overlooked the roof of another. Once-residents still come back to see long deserted interest points such as Saloon Canyon, Brown Jug Wash, Gamblers' Tunnel (where men off-shift played poker as many as fifteen games going at one time), and "Little Cananea" and "Little Hollywood."

It had a post office for 36 years, part of the time sending mail over the rough divide to Sombrero Butte via Shorty Neal on muleback. Mammoth, 14 miles down a rough mountain road, was its trading point. From its start in 1876 Mammoth has been a center of mining business. But for thirty or forty years it was better known as a wild-and-woolly cow town where liquored-up cowboys rode their horses into the bars and recklessly fired their guns.

The Schultz Mine (later called "Tiger") and the Old Mammoth Mine and The Mohawk kept the Mammoth businessmen in a state of modest prosperity for nearly fifty years. However, it was not until the 1950s that the Lower San Pedro Valley entered the big mining world through the development and operation of the San Manuel Division of Magma Copper Company.

It would be hard to evaluate the monetary impact of this great copper mine on the long isolated villages of Oracle and Mammoth and of course the third member of our "Tri-Community" the new town of San Manuel.

The biggest benefit to San Pedro people is the fine state Highway 77 cutting through the curving ridges from Oracle down to Mammoth, over a new bridge, and straight down the river to a finer new bridge across the Gila at "Winkietown."

Along with electric power and natural gas, this highway is our entryway to modern living. On a late Friday afternoon 54 cars and campers pulling boats passed through Mammoth in one hour on their way to the playground lakes of central and northern Arizona.

It is a picturesque drive and in springtime it is gorgeous with flowers. Blue lupins and yellow brittlebush, with here and there tall rosy pentstemens (wild hollyhocks) line each side of the pavement; and the hillsides are splashed with golden poppies or, later, the soft yellow of the paloverdes. A Kearney woman was so impressed with the floral display around Mammoth as she drove through on her way to Tucson that when she arrived in the city she joined a Wild Flower Tour. To her astonishment they took her back to Mammoth!

Highway 76 leads off from 77 six miles to San Manuel. The state highway department is now engaged in extending this road upriver to Benson so the Lower San Pedro Valley, after all the centuries, will at last enter the big world over the mountains. There will be picnic areas along the river under the great cottonwoods; and old Indian ruins, such as the Reeves Ruins recently excavated near Redington, will be accessible.

Besides excellent roads, the Lower Valley now has fine schools, hospital facilities, and a population affluent beyond the imagination of yesterday's old-timers. A yearly payroll of $17,500,000 wipes out poverty and sweeps in modern homes, cars, appliances, and luxuries such as boats and paid vacations. The hardpressed pioneers of the nineties would be bug-eyed at this incredible wealth although they might be shocked at the damage progress has done to the countryside.

Wesley P. Goss, president of the Magma Copper Company, San Manuel Division, says the life of a mining operation depends on the size of the ore body, the rate of production, and the ability to maintain a profitable operation. Given favorable economic climate, he thinks the San Manuel mine will probably continue producing past the year 2000. Because of recent purchase of additional properties, extensive expansion is being planned for the next five years.

In his position he can choose his homesite, and base his selection on good climate, wonderful scenery, congenial companionship, and outside accessibility as well as privacy and security. It is significant that, in answering a direct question, he wrote: "I think the San Pedro Valley is a pleasant place in which to live."

THE SAN PEDRO TORPEDO

Where the San Pedro River meets the Gila stands the town of Winkelman today, named for Pete Winkelman, a pioneer stockman. It is a colorful part of the Gila Valley and well worth a visit. If you come over the tricky mountain road from Globe, you will see some beautiful country and have a stunning view of the rushing Gila River far below, and you will want to pause in Winkelman. This town has made popular, at least locally, a drink called the San Pedro Torpedo, and its ingredients are tequila, gin, rum, whiskey, vodka, lemon juice, and Coca-Cola. After giving that serious thought you will be certain to order anything from a glass of beer to a glass of

alias THE GILA MONSTER

milk. But the caliber of the men, and presumably the women, of Winkelman who consume the San Pedro Torpedo is somewhat fascinating, and you wonder just how many "torpedoes" the average habitué can imbibe.

"I suppose nobody can take too many of them?" you suggest cautiously to the bartender.

"That's right," he agrees. "I've never seen anybody take more'n three and walk."

"The ingredients are rather strong stuff," you concur.

"Hell, no that stuff won't hurt you. What gets 'em down is the water in it. That comes straight out of the Gila!"

THE INDIAN WARS IN ARIZONA – FOLIO 1

The eight color prints shown on pages 8-9, 35, 44-41, and above were reproduced from the original oil paintings by Francis H. Beaugureau, owned by the Valley National Bank of Arizona, and used in this issue with the permission of Walter R. Bimson, board chairman of the Valley National Bank, and sponsor of a most important and historic series of more than 30 paintings depicting the phases of military operations in Arizona.

The eight scenes shown herein comprise Folio I, The Indian Wars In Arizona. Folios II and III will be issued in the future.

As part of civic promotion designed to benefit the Phoenix Fine Arts Museum, The Valley National Bank has authorized publication for a limited edition of full color lithographed prints, for collectors, historians and scholars, suitable for framing on special paper, with accompanying authenticated historical information about each scene, all contained in a handsome envelope folder.

Prints measure approximately 9 x 12" on 12 x 17" individual sheets.

A very limited quantity have been reserved for our readers at only ADDRESS ALL MAIL AND PAYMENTS TO: BEAUGUREAU PRINT PROGRAM OPERATIONS SERVICES DIVISION P.O. BOX 71 PHOENIX, ARIZONA 85001

Fly from Page 39

Frank King, one-time cowboy who was then Special Deputy Collector of Customs at Nogales, chanced to be coming up the street. Realizing what was taking place, King opened fire on the bandits as they headed northeast at a gallop.

The pursuit of this gang has been chronicled in a number of publications and apparently through different eyes or at least with different hearsay information. It would seem that Frank King was in a position to know the facts as well as anyone and he confirmed the facts in more detail than is found in his book Wranglin' the Past through a personal letter in 1950. According to King, the posse which was soon formed to pursue the bandits lost them on the night of the robbery, which had occurred at noon, and returned to Nogales.

Meanwhile the wires had been busy and Sheriff Bob Leatherwood of Pima County and Sheriff "Buck" Fly of Cochise were alerted. The posses formed by the two sheriffs were soon joined and the trail of the bandits finally led to Skeleton Canyon in the southeastern corner of the state. This was in the vicinity of Geronimo's final surrender in September of 1886. It is a desolate region east of Apache, the canyon winding through the Peloncillo Mountains. Here in 1882 Curly Bill and his band of outlaws had ambushed fifteen Mexican smugglers and left their bodies strewn over the canyon floor.

It was a good place for ambush, as the outlaws were well aware. When Sheriffs Fly and Leatherwood entered the canyon with their men, the outlaws let loose a deadly fusillade, killing Frank Robson, a government inspector of customs and wounding another posseman.

The pursuit of the bandits was stalled, due to the outlaws' commanding position, and while the posse was attending their casualties, the gang slipped down into Mexico.

Frank King wrote: "Fly was a fine man and top-hand photographer, but he had no peace officer experience." That sentence summed things up very well. Fly was truly a tophand photographer, called by some the Matthew Brady of the West. His works rank with those western pioneers of the wet plate William H. Jackson, L. A. Huffman, Henry Buehman and Adam Clark Vroman.

The brief and undistinguished law-officer career of C. S. Fly came to end with 1896. Photography now in Tombstone's dwindling population offered no prospect of a sufficient income. Meanwhile, Bisbee was showing signs of prosperity. The Copper Queen mine with which Dr. James Douglas was actively associated was turning out valuable ore.

Torn between love for the mountains and his dedication to photography, it is reasonable to construct from the meager information available that Fly divided the final four years of his life between a small ranch he owned in the Chiricahua Mountains and sporadic photographic activities in Bisbee.

A man who knew Fly well, Earl Reed, reported some years ago that: "Mr. Fly had quite a ranch at Fly's Park. He had a few stock and a large garden in which he grew potatoes, cabbage, strawberries and just about everything that would grow well at that altitude. Volunteer potatoes and strawberries were still growing there as late as 1910 and possibly still do."

The Tucson Citizen commented: "Fly was a genial, whole-souled man who after his retirement from office fell by the wayside in Bisbee, where he conducted a photograph gallery almost up to the time of his death."

To a man of Fly's artistic temperament the drastic decline of prospects in the profession which he had pursued for many years was a heavy burden to bear. No longer was the sheriff's salary available to bolster his finances. He became depressed and fearful for the future. At the age of 51 his health began to fail. Adversity was the insidious disease with which his mind and body were unable to cope.

Camillus S. Fly died in Bisbee at ten o'clock on the morning of October 12, 1901. Mrs. Fly, still running the rooming house and gallery in Tombstone, had been notified of her husband's serious illness and left hurriedly for Bisbee to be in attendance at the bedside of the sick man.

The Tombstone Prospector eulogized: "Mr. Fly was a pioneer of Tombstone, having arrived in the camp in December, 1879, where he has resided ever since, sharing life's vicissitudes and leaving his survivors to speak the kindliest words of him. The bereaved wife has the sympathy and condolence of the entire community."