The Quail Garden

Arizona... the Quail Garden

Four different choirs of quail chant to the luminous pink-gold of Arizona sunrises. From Oak woodlands to desert bottoms, Arizona is a quail garden.... Gambel Quail, the most widely spread, call out across the Sonoran desert and chaparral country. Scaled Quail bring additional beauty to the grassland winds. Mearns Quail are the country gentlemen of the grassy-oaked hills and the pinyon-juniper and oak-pine highlands. Masked Bobwhite Quail are striving to hold processional services in the formerly lush grasslands of Altar Valley.This splendid gift from the Sonoran desert has brought people closer to the awareness of nature than any other bird of the wild.

Thank God for Gambel Quail!

To make the gift more meaningful, the Creator endowed this plumed prince with the power to adjust to the pressures of civilization. He tolerates humans well if the humans use sufficient wisdom in their custodianship of the land.

Arizona residents and many visitors place high on their list of memories the sight of a worrying, solicitous mother of fourteen sprightly chicks threading their way through desert thorn and cactus spine. Their hearts, like mine, grow soggy with affection for the proud papa, perched high on a palo verde limb, who sounds the all-clear to the foraging family below.

To the bird lover, this quail is so many fine things that they cannot all be listed. To the casual observer, he is a quick surge of joy. To the hunter who roams the autumned ridges, he is the keen thrill of brisk desert mornings and excellent table fare. To the wildlife biologist, he is a mixture of all these things plus a challenge to his life's work. To an artist, he is a hunger to possess him on canvas.

The greatest enemies on the fringes of suburbia to the Gambel Quail are the bulldozer and the housecat. The greatest preserver is the grand total human affection which consciously or unconsciously does the right thing to perpetuate the kind of living conditions which quail can cheerily call home Along with trees and shrubs, watered lawns and gardens create desert-edge recreation areas for pampered coveys. Tons of bird seed are spread annually from five to twenty-five pound sacks, which find their way into grocery carts along with human vittles. Day by day, month after loving month, the cups of grain are showered on patio fringes. Hour after hour, human hearts twinkle to the special antics of coveying quail.

To keep a good thing going, quail remain sufficiently aloof and tend to their own affairs. No offending familiarity, no pigeon-like indiscretions on the family car, no sparrow-like insistence to take over: only brisk and pleasant visits with charm and grace and a season to show off with uncontained pride a remarkably long column of well-disciplined young.

In the lovely rural areas patterned throughout Arizona's heartland, the quail prosper mightily where native brush crowds the irrigation fence rows. But where cold farm economics is applied with sterile rigidity, the quail fail along with all other wildlife. Miles of gleaming fenceline atop barren berms hum out the wildlife epitaph. For when the shrubs and grasses are burned and poisoned out, and the palo verdes, mesquite and cottonwoods go, the short-term graphs of farm economics jiggle up and the long-term charts of the former tenants go blank.

Here and there, resident farmers defend their wildlife friends with a special tenacity. To many a farm wife, the quail that call through the sweet morning air are an essential tonic for the day. A covey standing shoulder-to-shoulder on the rim of a brimming water trough and dipping in near unison to sip of the sparkling freshness is a poem of peace. An evening covey coming in from afield, canting one way, then another on set wings to drop to a dusty stop amid the chicken's scratch is a welcome daily visit... The bursting-out of coveys ahead of the farmer enroute to his ripening rows is a greeting of old companions under the sun. And, on occasion of severe desert drought, the quail can become a source of trial to his farmer host: The succulent young greens in his fields may turn into more of a quail commissary than he can afford, and paradise isn't paradise any more. But seasons change, and the rhythms average out, and the scales of pleasure outweigh the passing unhappiness. And the quail continue on.

"Buzzing Of The Bees In The Pronwood Trees"

Pottery designs and pictographs of the Indian pioneers of the desert land preserve the quail image. He greeted the Spanish explorer and the frontiersman, and today the television series of "High Chaparral" would not seem authentic without the ranch headquarters background music of quail hymns.

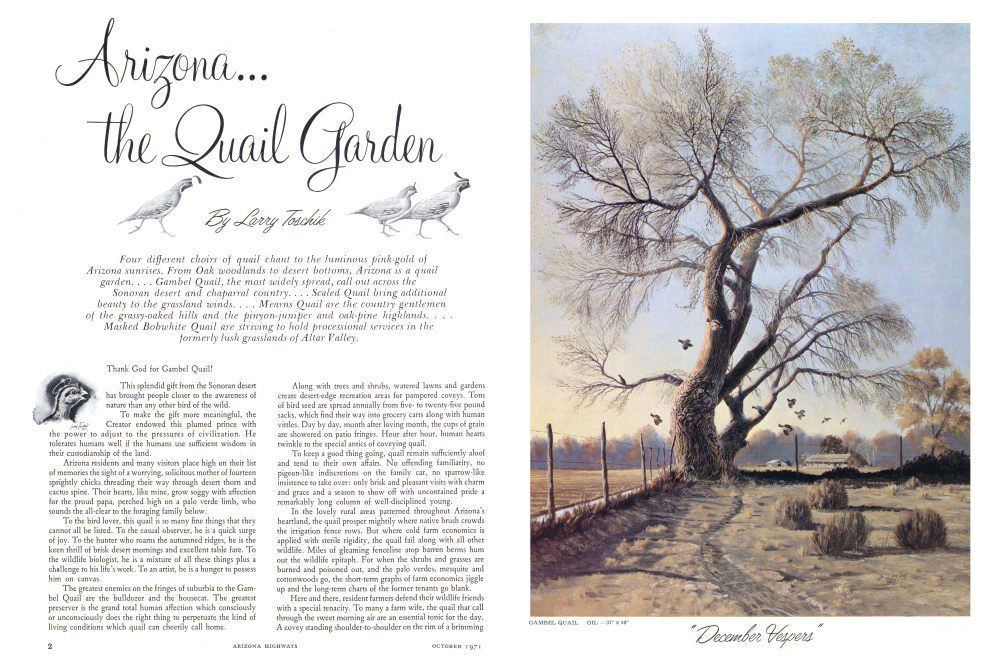

The painting, "December Vespers," is a tribute to one of the priceless moments of contact with life's basics those threads of grace that bind the working day life with the fabric of reason for living. The lowering December sun is caught in the filagree of cottonwood limbs. The dimming light of day brings on the supper-light glow in farmhouse kitchens. A quail calls from his lookout station to gather the covey to the water's edge. From harvested grain fields, the gleaners whir off to ditch bank gossip and perhaps a last-of-the-day dusting in the soft, soft earth along the gophered berms. This is a time of clean, pungent desert scents mingling with the first whisps from mesquite glow-ing in home hearths to fend off the night's growing chill.

In moments, the musical whirring of Mourning Dove wings will blend with quail prayers as they gather to water. The whistle of Pintail pinions cleaving the twilight sky may join the chorus as they circle an irrigation tail-water pond in the thickets beyond. Evening glow, fading rapidly, fills the wanderer with the gentle melancholy of urgency to be at home with loved ones.

This painting is a binding together of personal reactions to a mood of nature with the architecture of painting structure, and as such was a true labor of love.

The desert quails are not absolutely dependent upon drinking water for survival. They do thrive well in watered areas and drink as we would expect them to do. However, they also survive in the most arid of regions far from any free source. The Gambel Quail young are born and raised in Arizona's driest months of May and June. I've seen many quail families near water holes and I've also seen many groups miles from any open water. And since quail live out their lives within a radius of approximately 500 yards of their roost, that puts the open country birds out-of-range of distant water.

Those that are near water, use it; those that are not seem no worse for the lack of it. More quail are seen near water for a variety of reasons, most important of which is the increased abundance of food and cover.

Hunger is the greatest predator of wildlife. Hunger means habitat that is lost, either from natural conditions or, sadly, from the increasing, helter-skelter misapplication of progress for progress's sake. Quail are victims of this condition as are all forms of wildlife.

Several years ago, a succession of matchless spring days undermined my sense of responsibility to my tubes of paint and I abandoned all to flee to the desert. My drive took me by chance along a winding, climbing road through some prime desert country. Along with many other desert plants, the cholla was in full bloom. The impression of this seemed to hammer home the hardest. Ordinarily, my painful encounters with this "Satan's lily" caused me to lose any desire for intimate acquaintanceship. Migrating song birds flitted about, looking like pieces of an exploded Mexican serape colorfully tumbled by the breezes. Glimpses of Cactus Wrens busy in the cholla became subject matter for a picture to be born later for a current series of prints for an automotive dealer. As I had never seen whole hillsides of cholla in such lush bloom, my spite for this pain bush seemed to leach out to me. In the distance, I spotted the semaphoring blades of a windmill. The message read water, and that further read birds and possibly quail. I found the trail to the overflowing tanks, which were surrounded by a holding corral for cattle. Dense mesquite crowded one side nearest the wash, and my newly-patched up cholla friendship was further cheered by a scattered garden of the burnished golden blooms. When I stopped the muttering car near the tank, the desert songs wafted through the windows. Along with the high, flutely fife-like calls of a Western Meadowlark, a symphony of dove cooings and quail plaints filled the air.

Movement at the base of a massive, fruit-laden prickly pear caught my eye. So many thumb-sized baby quail were scurrying beneath the statuesque columns and pads that I couldn't count them. A fussing mother murmured about, keeping some semblance of order, though she looked more like a parochial school nun with a windblown whimple at recess time. Her crest and top knot raised and lowered with her varying anxieties. Several self-satisfied males were lolly-gagging around, all puffed up, with top knots hanging down and talking up a storm. When another male dropped down from a brace on the windmill tower and joined the family at the cactus, an idea for a painting began to take shape.

count them. A fussing mother murmured about, keeping some semblance of order, though she looked more like a parochial school nun with a windblown whimple at recess time. Her crest and top knot raised and lowered with her varying anxieties. Several self-satisfied males were lolly-gagging around, all puffed up, with top knots hanging down and talking up a storm. When another male dropped down from a brace on the windmill tower and joined the family at the cactus, an idea for a painting began to take shape.

This was too much for me alone. My wife, Ceil, had to see this. Back to town I hurried to set the trap for her heart. Early the following morning we coasted the car as quietly as possible to the edge of the oasis. We listened for a while in a kind of stained-glass reverence to God's half acre. Several broods of quail were roaming toward the corral. They looked so vulnerable to the bristling harshness of the sharp-stoned desert floor. How could they possibly survive the severity of this land in spite of blooms, bees and bird calls?

One group was again playing tag, or whatever quail chicks play, among the formidable buttresses of that cactus castle. My cameras checked, we cautiously got out of the car. When we approached to about fifteen feet, the mother quail screamed an alarm, and ran and flew off, squawking. The babies fretted in confusion. We squatted down within inches to look at them. As our ominous presence became too much, one by one they zipped out of their protective battlements and streaked to other cover. Now Ceil became alarmed and feared for their wellbeing. I told her to go slowly back to the car. Then we sat and watched. The silence that had now descended upon the disturbed garden was presently broken. The mother quail dropped back down to the ground and called softly. The note had a querulous sound of fear to it. She called again, more sure. Within moments, furtive buttons of golden fuzz detached themselves from hiding places and darted from shadow-to-shadow like animated cartoons to finally regroup in a panting, cheeping family.

From this experience, and a follow-up trip when I found the shed skin of a rattler (with all its implications) at the base of a cholla in bloom, the final concept of the painting, "The Soft, Sweet Sound of Spring" (ARIZONA HIGHWAYS, May, 1970), was born. The James Silvers of Tulsa now share the gathering of those moments.

Anyone who has had just a nodding acquaintance with quail has a story to tell. These gentle birds fit comfortably close to the warm hearthstone of the human heart. Yet, to be fair to the splendid plan of creation, you have to step out of the aura of emotion. Freed from this blinding force, you can observe with a more practical compassion.

As peace loving and gentle as they are, when that certain season comes, the males go the way of all flesh. Some of their mating fights end with bad lacerations and total exhaustion, and possibly fatalities. Even a paired couple might do battle together against another indiscrete male. After the young are hatched, daddy takes on his full share of parental responsibility, and may even sacrifice his life for family protection.

I had a wonderful opportunity to do some quail watching last summer. The study had become a side event to a Bighorn Sheep tallying mission. This census has to be done at the fiercest time of summer's heat before the rains begin. The sheep are compelled to visit those few isolated natural tanks which hold some water during the driest time of the year. This makes for reliable tallying of the herd, a chance to observe their physical condition and to treat the waterholes if necessary. This is no easy task in the unbelievable heat in Arizona's remote desert mountains.

I was teamed with Bob Hernbrode, of the Arizona Game and Fish Department, to tally a natural water catchment in a remote box canyon near a furnace called the Eagle Tail Mountains. After a spine-twisting dawn attack on a primitive desert "trail," we four-wheeled to a stop below the approach to the canyon.

The canyon structure was in two layers: a dramatic overburden of craggy sloughed-off basalt and a base of tufa, which was compressed as hard as limestone. Centuries of brief but violent summer storms had channeled the run-off from the main towering basalt cones and cut the canyon. The upper box end was made of two irregular giant steps. Into these, the gritladen water had ground out two deep basins. Now they held the precious residual water from infrequent showers.

We proceeded on foot, laden with our own drinking water and cameras, to scramble down and back up the opposite wall to a shallow indentation. From this cave we had a box seat view of the waterholes. When the sun punched over the canyon rim, it swung with authority. To think that that brilliant disk was 93 million miles away and could still finish frying the egg on your face was something to consider.

After we made ourselves comfortable upon the sharp, splintery basalt floor, we dutch-ovened ourselves for twelve hours. In spite of the fact that no direct sun reached us, the glaring reflection off the opposite canyon wall gave us a hurting burn. We repeated this for two days. We did see a bighorn ram, deer, coyotes and quail. The quail stole the show andthey taught me to form no solid opinions about them from only a single encounter. The first day was throat-squeezing humid. I do not care to know the temperature. Any piece of metal gear caressed by the sun was far too hot to touch. Cumulous clouds grew from whisps to brilliant white cotton puffs hung in a deep cobalt sky, to awesome thunderheads rumbling across the manganeseenameled desert.

Covey after covey of Gambel Quail called in fretting complaints all through the day. The canyon was never silent. The coveys were family groups composed of one or more adults and varied numbers of half-grown young. Some disaster must have befallen the mothers, because most of the coveys were being led by adult males. They wound their ways up through the tangled, thorny thickets from the canyon below the tanks and from the sun-torched drainage above. I have never seen such unhappy birds. They dragged along with wings akimbo like old-time Dutch housewives hiking up their gray, voluminous skirts.

The main waterhole was in a deep pocket in the lower head of the box canyon, guarded by a fifteen-foot high sculptured battlement of hard tufa. To get to the water, the quail had to surmount that barrier. As the first covey approached, we expected them to fly up to the ledge, then drop off to water. Instead, they laboriously crawled up the sheer face from one meager claw hold to another, complaining and jawing every inch.

Several times, two coveys approached from different directions, and, having gained the bench at the top, accidentally intermingled. All hell broke loose as jealous guardians set about untangling their broods. They weren't going to have any fraternizing and tempers were short.

At times, they had the appearance of a slow parade of blue lizards squirming up the cliff face. One large covey approaching from above negotiated a lengthy water-carved ledge and then, eager to get out of the sun, lined up in a long single file in a pencil-thin shadow of a shallow seam in the tufa.

A distant Red-tail Hawk swung down an inclined plane of air, dipped into the canyon and swooped as if to land on a rock pinnacle. Instead, he caught a thermal and literally vaulted in breathtaking spirals until he was lost from view against the monumental escarpments of a towering thunderhead.

On and on through that endless day the canyon rang with quarrelsome quail. Had we left that evening and not returned, I could have sadly concluded that the quail in this fearsome place were very hard-pressed to survive.

The following morning, the sun again exploded over the fanged ridge of the eastern mountains, but during the night, the shepherds of the clouds gathered their flocks and had gone to graze elsewhere. The temperature was the same, but with the moisture gobbled up, the air seemed livable. When we returned to the cave, we were immediately aware of the change. The canyon was considerably more quiet than the day before. The same coveys appeared, but now perkily retraced their prior day routes. When they approached the tufa battlement, they flew up to the bench as respectable quail should. All leaders held tighter reins. No sloppy intermingling, no squabbles, just pure and undiluted quail business. Their calling had none of the plaintive "human" aggravation of humid yesterday.

But all was not cool beer and skittles. One testy argument did break out that evening at an intersection of trails beneath our cave. The drawing of that is on page 7. I modified it to show all quail as adults, because a half-grown quail is a pretty ratty-looking affair, and not a pleasure to paint.

A Difference Of Opinion

Our return to camp was speeded by the promise of steaks broiled over ironwood coals and ice chests loaded with cool things. Our route from the cave was to climb out the right side and over the top above the cave, then back down a cut in the wall to the left, easier to negotiate. When I worked my way out over a small projection at the cave entrance, my foot nudged a loose stone. As it knocked its way down the cliff, I froze and couldn't move. Bob came back along a slant, narrow, gravely-foot way, took my gear piece by piece, and gave me a hand hold up over to safer ground. My panic embarrassed me, and I thought of the ease at which the Desert Bighorns flow up and down these broken cliffs, and how the diminutive quail negotiate the tangled ways. When a person gets to know some wild creature, there is a continuing growth in the joy of discovering what seems to be human mannerisms. On occasion, this assumption will get out of hand: There is danger in considering that a quail, for instance, would be just a tiny, feathered human. But even the wisest, most brain-developed creature on earth has not begun to comprehend, even in the slightest way, the scope of the special facilities given to man. It is not that animals have human ways; it is simply that humans are animals endowed with an extra set of intellectual gifts. Up to this point, we share many of the same characteristic life functions. Even some insects live in highly-organized societies. They have workers, bums, servants, leaders and soldiers. They build, harvest, store supplies, herd their "cattle," and even raise their own crops. These patterns repeat themselves up through the life chain to man where the struggle to perfect them goes on and on. Because we have been given added intellectual gifts, Genesis tells us that man was also given dominion over all. In the total of human history, the word dominion is probably the most tragically misinterpreted piece of communication. Few comprehend the full meaning of that mandate; many are indifferent; and most misinterpret and plunder the domain. This last seems to have been the overriding condition of man. Now that we are being crowded into bumping rumps and elbows with our neighbors, humanity is suddenly listening to those wise students of nature who have been fairly driven to screaming their warnings to take care of what is left or we'll all go down the drain. Wildlife is rapidly being given importance. Now that the human race is beginning to grasp the full concept of the limited and perishable habitat on this unstable ball we call Earth, it is also beginning to recognize the vital niche each creature must have for mutual survival. Wildlife and nature societies and individuals have recognized this concept all along, and have earned honored places under the sun. The game and fish departments of all the states, and their federal counterparts, are, in most cases, fully committed to the noble goal of intelligent management of all wild species. Harvest and replenish is Genesis in action. Those total preservationists who oppose intelligent wildlife management are as much a danger to wildlife survival today as the wanton, law-breaking kind of "hunter," or the greedy "profits above all else" type of progressive, or the habitat-be-damned kind

Mrs. Lee Tomerlin tells a delightful story about Gambel Quail. It's the kind of experience the residents of the perimeter areas of Arizona towns and cities can expect. The Tomerlin's home is situated against a rocky hillside on the north side of Phoenix. One room enters out to a small, enclosed patio. A drain pipe goes under one wall. There is no outside gate. One morning, she was alerted to a commotion in the patio. A covey of Gambel chicks had entered the patio, apparently through the drain pipe, and frantic mother flew in to get them out. For some reason, they refused to go back through the pipe. Maybe they were so chastised for having gone through in the first place that they weren't going to buy another beak lashing from doing it again.

All day, Mama tried and failed to solve the problem. She showed them how to hop up precarious footholds, but they just couldn't hack it. As evening wore on, she finally bedded down with them to make the best of a nasty situation. Dawn came with a new rustle of commotion. Mama had help. A bossy aunt had taken command. She stood upon the wall and supervised all proceedings. With a cousin to cry feminine encouragement from outside the pipe, with Mama herding from the patio side, and with Aunty watching the progress from both sides at the top and issuing orders, the whole evacuation was completed as slick as a wartless pickle. Mama flew out to resume household duties where all respectable quail belong. So ended another episode in the delightful relationship of quail people and human people.

The least observed, and probably the more interesting, quail is the Mearns. This quaint quail is called by many names: the most upsetting is "Fool" quail; the most descriptive is "Harlequin." He is also called "Massena" and "Montezuma." The Mearns' range is fairly restricted in Arizona. He perfers good, high hilly grasslands, studded with brush, oak and juniper, and open stands of pine. This puts him in a small, south central section of the state, with some overlap east and west, and a portion of the White Mountains and parts of the Mogollon Rim country. Since its food requirements differ from other quail, its feet are much heavier and the claws are exceptionally welldeveloped. The drawing on page eleven shows a comparison with Gambel Quail and also with a perching bird. The structure of quail feet in general is sturdier than that of song birds. Actually, the feet are very close miniatures of that king of American ground birds, the wild turkey. Mearns Quail have special needs. They dig into the hard dry soils for nut grass tubers, and that requires some pretty hefty tools. Its beak is even stronger for the same reason. The Mearns is called "Fool" quail because it holds to its cover and can be approached within striking distance. Men have walked right up to within inches of them, and the birds have held still. Because of its bizarre patterning and back camouflage, he is hard to find in the grassy cover and he knows it. For this reason, too, occasional alarms flare up that the Mearns is being wiped out. But field checks with hunting dogs have demonstrated the contrary. Weather being right, Mearns does well. Like other quail, drought, overgrazing and the subsequent loss of habitat are his worst enemies. When the assignment was approved to do the story of Arizona's quails, I decided finally to show some as formal portraits and others as vignettes of quail lives. During my basic research, I learned more about the Mearns' habitat and almost immediately decided on a snow scene thereby telling more about Arizona's range of climates.

My field research carried me into the Gardener canyon of the Santa Rita mountain country. Again I experienced the delight of discovery. In this case, because I had a purpose, I became aware of the richness of this land, both in esthetic and physical properties. My guide to this land showed me so many varieties of grass, each with its own characteristic grace and structure, that I kept marveling at it. The excitement to paint "Strangers on Our Hilltop" became difficult to discipline. After playing a hunch about the possibility of specific characteristics of the rabbits of this area, I secured a specimen and was glad I did. Otherwise, I would have had a big-eared desert cottontail instead of the right kind pondering the covey of Mearns under the oak shrub.

The reason for calling Mearns "Harlequin" is obvious enough. Its body proportions are off-trail of other quail. Its tail is too short, legs too heavy and set too far back, and its coloration and feathering is really unique and decorative.

Scaled Quail often share part of their habitat with Mearns and Gambel Quail and Masked Bobwhite. They are desert grassland birds, though, and seemingly have such specialized habitat requirements (especially in climate), that their range is limited. To the uneducated, some grass country looks just like another, and often the proposition to expand their range to other areas of the state is suggested.

However, Dave Brown, an intensely-dedicated and knowledgeable wildlife biologist with the Arizona Game and Fish Department, as the result of a skilled research study, found that the present range of this bird is bound to its limitations. The Chihuahuan desert's characteristic vegetation, and the Sonoran desert grassland and plains-grasslands with the proper variety of shrubs combined with a summer rain pattern dictate the habitat. So in Arizona, "Scaleys" will be found in the southeast-ern grasslands quadrant and in a small area near the New Mexico Transplanting elsewhere would probably be futile.

Aside from coloration, the Scaled, Gambel and California Quail (of which Arizona now has a small resident population from escaped penned birds up near Springerville) share a feather pattern relationship. All three have the white-streaked flank feathers. Gambel and California have black top knots, and Scaled and California have scaled breasts. All three are great runners and flush only when hard-pressed (with infrequent exceptions). But the ground distance champ is the Scaled Quail. In his deep grassy habitat, his running ability is an efficient safety device from all predators. Combine that with an unobtrusive coloration and he's got it made. He earned his name "Cotton Top" from the fluffy white crest, which becomes quite obvious when the quail raises it fully.

Summer rainfall means grass, and grass means Scaled Quail.

In Gambel Quail country, rainfall from October through March is so essential that it controls the development of their reproductive organs and governs their mating activities. So closely is this related that quail populations rise and fall with the rain gauge records. But another factor has had impact on the quail census, and that is the grazing usage of the land. Where overgrazing has abused the land, the quail, especially Mearns, are hard-pressed to survive. In certain areas of Arizona, the Scaleys have been on famine rations for a long time. Hang a drought over that and you do not need to be a wildlife scientist to predict the sad news.The one steady breath of encouragement is the ability of quail populations to bounce back if given a chance; and the fact that dedicated men are constantly at work to correct bad situations where they can, and study and test new solutions are refreshing hopes.

My first meeting with Scaled Quail was in an abandoned vineyard in the Santa Cruz River Valley. I heard the curious and delightful quail gossip coming from a heavily overgrown and very deep erosion cut along an unkempt fenceline. With much caution and apprehension about rattlers, I negotiated my way through a wall of matted grasses and weeds. Snarled barbed wire caught at my clothes. I squirmed down under the dense overgrown mesquite limbs, and felt the unseen edge of the cut bank break away beneath me. I dropped five feet into the ditch like a 185-pound sack of refuse. My only injuries were a bleeding scratch on my cheek, where a mesquite thorn kissed me a happy landing, and then, of course, my shattered dignity.As I crashed down, the quail covey exploded up, so the down and up action in that wash was a Laurel-and-Hardy scenario. I sat in private embarrassment while droplets of burning sweat vividly identified the exact location of my cheek wound. My discomfort was promptly consoled away. The sand bar on which I was sitting curved in shadow-patterned and gleaming-cream whiteness through the bottom of the deep wash. Mesquite branches embraced in a dense canopy overhead, filtering down a pure greenish light. Where the force of the infrequent runoffs had undercut one bank and molded a sweeping curve of clean sand, it deposited a mosaic of smoothed desert stones against the other. Dead limbs in polished grays protruded from the flowing contours of the water-laid sand. Several bright yellow miniature blossoms hung suspended in a shaft of sunlight against a burgundy-umber shadow.

Before I could move, a couple of quail murmured to each other and strode out from under a mass of roots, scarcely ten feet away. My first close-up look at Scaled Quail! Within seconds, the covey began to return. In twos and threes, they fluttered down out of that green ceiling. They showed no signthat I was there. I could scarcely breathe. Lucifer's personal fly explored my face. Between fighting visions of its horrible germladen feet slogging around on that thorn scratch and watching quail puttering around, I was taxing all the self-control I could command.

Several quail found a pad of silt beside the sand and took to some serious dusting. All the time the busy clan kept up a goodnatured, almost giggly conversation. Every once in a while one would have something important to say, and he or she would dominate the discussion. Their talk sounded very much like rubbing a wet finger quickly back and forth on a small spot on a window pane.

At last, flesh and fiber, bone and fat could take no more. A cramp in my bent leg said, "Move or die." I moved and before I could do a decent blink, I was alone in the wash with a cloud of dust and some settling feathers.

I had never had a chance to observe quail like this before. No, the pratfall is not necessary. But what I did apply again, quite by another accident, was to get into a difficult and secluded spot where the quail hang out and to just be still. An old truism of the wilderness is that if you just sit quietly, eventually the wildlife will come to you.

Trying to find my way through a dense stand of salt cedar in the Gila River bottoms (in Gambel Quail country), I took a wrong turn and found myself crawling toward a sun-burnished grotto. Frost had turned the feathery greens into rich golds and burnt oranges. A tawny, thick, sun-dappled carpet of powdery tamarisk leaves glowed with a light of its own. In this private enchanted garden, Gambels were loafing away the noontime.

In such safe seclusion, they became a different kind of bird. In the open, quail are slick, streamlined beauties of quick action. Alert and high-stepping, they do not tarry long in one spot. But here in their living room, they had let down their guard. Man, this was home! A place to expand. Some were snuggling down into pockets of talcum powder dust. They squiggled and fluttered with supreme quail happiness. Others snoozed or gossiped. Those which puttered about were round painted balls with heads tucked back and down and top knots flopping. They walked with a strange cuteness, their bodies held close to the ground and legs bent. Each step was slow and well-placed. And their talking never ceased.

These mannerisms are sometimes displayed around the feeding stations near out-lying homes. Quail hatched and raised there adjust to the daily activities of humanity and the relative safety of gardened lots. How they survive the night-prowling cats is a praise to their wild abilities. Certainly they lose some of the clan in terror-filled nights, but like humans under pressure, basic instincts are honed sharp for self-preservation.

Gambel and Scaled Quail subsist on a varied diet ranging from flower buds to seeds, from insects to green plants. The hard, shiny mesquite bean is a heavily-utilized food of Gambel Quail. Here lies a story of animal interdependence not too pretty, I suppose, but an important fact. Since the pod of the mesquite bean is too tough for a quail to open (it's even tough to a certain degree for a man), the birds rely upon the seeds passed through the the digestive system of coyotes or cattle, or other animals.

With the drastic lowering of the water table in Arizona, vast bosques of mesquites have perished, and others are going fast. Couple this with total vegetation eradication from stream bed banks by a government agency, the habitat loss is appalling. So those who manage wildlife populations have quite a battle on their hands.

Although the dense thickets of mesquite are not in themselves good quail habitat, the fringes of it are, and so are the loosely-spaced trees with brushy cover and mixed grasses. The thickets themselves are evidence of a historic form of land abuse. Overgrazing by livestock leads to increased usage of mesquite for forage. Those seeds which pass through the digestive system and are not found by birds are planted widespread by the inevitable processes. The resulting increase in scrubby mesquite in the highlands becomes accumulative as more grass-lands are taken out of production. When a natural ecological plan is disrupted, the resulting imbalance can have long-term, adverse effects. In the near future, we'll know how the dropping water table fits into the picture.

Field research on wildlife is unlocking many secrets of relationship effects between man and nature. The knowledge is welcomed by rancher and nature lover alike. A rancher has a survival battle, too. Before he can raise cattle, he has to raise grass. In the process of good range management, a bonus of quail and other wildlife results.

The more you get to know the lovable quail, the more you respect them. The survivors of a covey would have quite a story to tell. Research by wildlife biologists tells it for them. Upon their complex findings, the recommendations for insuring quail prosperity are founded. In the process, old myths are destroyed. As a layman, if you focus attention on the predators of quail, you can be mistakenly taken in by what would appear to be a macabre tale. Reptiles, coyotes, hawks, skunks, ants, man, rodents, disease all raise such appalling images of destruction that you wonder how quail can survive. But nature unabused, or properly "dominioned," works in wondrous ways and keeps a delicate balance of good and bad, insuring survival for all.

When approaching Altar Valley in the mountain grass-lands southwest of Tucson, the presence of Conquistador history comes hauntingly alive. The trail-gaunt men, soldier and padre alike, wound their way through the waist-deep golden grasses, flushing coveys of Bobwhite Quail. Whitetail Deer and Javelina yielded to their approach. Heralded by the cornet throats of many kinds of song birds, and with cloud banners rampant on the battlements of mighty Baboquivari Peak, these remarkable explorers were unaware then that they would stir the souls of men centuries beyond. They left a legacy of land names which roll like drums across southwest history.

Years later, the J. Ross Browne party backtracked the Span-ish pathfinders and passed through this grand valley. They reported nostalgically the birdsong of the bobwhite which reminded them of their eastern homelands. These frontiersmen broke trail for adventurers to follow, and in the process of putting the land to other use, the settlers unwittingly punished it beyond its means of normal recovery. In the 1800's the comCombination of severe drought and overgrazing sounded the death knell of the Masked Bobwhite in Arizona. With the ravaging of the grass went the dependent wildlife, and in a relatively short time, the Masked Bobwhite disappeared completely from Altar Valley and other pastures of its range in Arizona.

Wildlife biologist Roy Tomlinson of the U. S. Fish and

Wildlife Service has spent 3 years in full-time study of the birds, both in Arizona and Mexico, to establish a scientifically-based, accumulative knowledge of this quail. Quail captured in Mexico were sent to the Wildlife Research Station in Patuxent, Maryland, where they were bred and raised to maturity, then returned to Arizona for studied release.

Ron Anderson and Bob Kirkpatrick, the resident Arizona wildlife managers, watch over the delicate survival problems, and Dave Brown, an encyclopedic authority on the plant cover of Arizona, advises on release sites. Dave is devoting a tremendous amount of his own time along with his department assignment in compiling an extremely accurate record of Arizona's vegetation and area climates.

Naturally, pictorial research about this rare quail is hard to come by. Those few study skins available are well-guarded for good reason.

If I do not know the living bird, I find it very difficult to portray it realistically from a mounted specimen. To overcome this problem, I was loaned a pair of live Masked Bobwhite to study. On short notice, I built the best quail Taj Mahal I could. I stocked one corner with clumps of native grass. After having the birds awhile, I learned more about their specific needs and added a rock and dead limb to climb on. Within days I added a shallow box filled with loose dirt: I think the birds thought that they had died and gone to Heaven. Such luxuriating in dust baths! They emptied the box almost daily. They loved pieces of lettuce so much that they could overcome their fears enough to snatch it from my fingers. They accepted me with less apprehension when I wore my old green jumpsuit, and regarded my new red one with panicky suspicion.

Their first calls were a repeated, short two-note whistle, with a kind of crowing resonance. I wondered after a few days if that was their complete repertoire. They crowed at about 5:30 in the morning and again around 4:00 in the afternoon, with infrequent bleeps during the day. When frightened, they kept up a low whinning murmur of worry. A sudden scare brought out a single screech followed by rapid clucking. One humid and cloudy day, they called all day long just like the Gambels in the Tank Mountain canyon near the Eagle Tail range had done.

One morning as dawn glowed against our bedroom curtains, we were awakened by a clear, deliberate "Bob . . . white." I thought at first that my daughter, Mary, who started her summer hospital job at dawn's early light, was faking me out. But when I looked out to check the birds, there was the male in full orchestral stride, head thrown back, chest out, eyes closed, and busting his little heart out with "Bob . . . whites." Their call is not as quick as the eastern bobwhite. There is a distinct pause between the bob and white and the last tone is on a slightly descending minor key, as if it has a note of sadness about its historic "exodus."

After the painting concept was underway, I discovered that the frontispiece of The Birds of Arizona by Phillips, Marshall and Monson shows a watercolor by William J. Shaldach in a similar Altar Valley setting. At first, I thought of destroying what I had done up to date, but then thought better of it, as this setting best suits the history of the bird in Arizona.

Of all the wildfowl I've painted, the feather pattern of this quail's back was the most difficult. Usually a design plan can be analyzed and a step-by-step procedure, arriving at a painted resemblance, worked out. But on this quail, it seems that theplan Of the back coverts changes from feather to feather in an intricate scrambling of broken patches. The heads of the male bird vary from bird to bird, and with age the white eye banner changes greatly. Some heads are all black.

Among the upland game birds, Arizona has an established population of Chukar Partridge and Afghanistan Whitewing Pheasant which were introduced into this land, and a resident population of Mourning Doves, Whitewing Doves, Bandtail Pigeon, Wild Turkey, Blue Grouse and migrant Wilson Snipe.

The two doves have dwindled from uncountable clouds of birds to a fraction of their original population. Rapid destruction of habitat from stream bed clearance, burning and agricultural clearing has put an end to the great flights. The dropping of the water table is destroying or has destroyed the mesquite and palo verde nesting stands in wide areas.

The quail populations yield and return with the changing pressures of nature and man. To be blessed with such a variety of quails is unique compared to most states. Their presence is a sweet accompaniment to the beauty of Arizona spring and the dramatic loveliness of the summer grasslands' rainy season. Their breeding calls are another kind of music. The timing of nature to coincide the blossoming of this land to the hatching of the chicks is beyond expression.

Even the most formidable of the thorny plants dress themselves with striking corsages of lingering beauty: soft violet ironwood, blazing green-gold palo verdes, yellow mesquite, vibrating red and gold cactus, purple lupine, orange poppies and on and on through color and variety. The superb, whiteflamed candelabra of the yucca above the golden grass, against the violet hills and the matchless blue of a rain-washed desert sky is a fitting setting for the gentle Scaled Quail.

The garden of the Gambels will leave you silent with unfound phrases of appreciation. When the timing of spring rain and temperature reaches its optimum, the muted beauty of the Sonoran desert becomes indescribable. Great stretches of desert hills become carpeted with countless varieties of brilliant wild flowers-masses of them banked against boulders and trees.

Saguaro cactus are always impressive to see. But a giant in washed green finery wearing a tight, rich bonnet of creamy blooms upon its head, and holding matching bouquets and reflected mirror-sharp in a quiet rain pool, is a visual experience of great emotional value. Mountain slope armies of them in bloom cannot be described. Wheeling hawks, Vermillion Flycatchers, ebony Phainopéplas and polished Goldfinches, bursting with the surge of life in the three-dimensional wine vapor of spring air, are a heritage to preserve. Include the sight of a quail family winding along the ground squirrel trails and you feel that among the choirs of angels observing the progress of Genesis, a seraphic ancestor of Disney made some suggestions.

Clouds crowd upon the mountain tops to build and build into million-ton giants of flashing grandeur. The whole cubic volume of air embraces mountain and valley, trees and you in this breathless thing called spring. And quail call and your heart replies.

As a courtesy to those requesting reproductions, a small edition of the six color pictures, the same size as they appear in this story, have been made on high quality print stock. They have substantial margins and are titled. The prints are available for $14.00 per set from the artist: Larry Toschik P. O. Box 6861 Phoenix, Arizona 85005

Already a member? Login ».