An Arizona Collector Taken With Tokens

John T. Hamilton III is a 34-year-old transplanted New Yorker with a token interest in Arizona history and the token multiplied one thousand six hundred times. He wishes it were an even two thousand, and maybe it will grow to that, given his hound-dog pursuit of something most of the rest of us never heard ofor didn't think much about even if we had: the pervasive trade token. This novel device comes in as varied sizes, shapes, colors and descriptions as the mind can conceive. It was the product of a merchant's needs coupled with imagination, someone's pixie concept in the remote past (at least as early as Greek or ancient Roman days, Hamilton believes), of how to corner a bigger share of what trade was going on, or even to tie it all up. The practice of trade tokening has continued almost to this day on pretty much the original pattern: as a means to stimulate sales in the absence of cash, and to nourish commerce, primarily one's own commerce.

Kings and emperors, or the secretaries to their treasure-houses, invented money and the ruler soon came to have a strangle hold on that. But the entrepreneur with the wit, if not quite the power, of his majesty's agents, quickly devised the trade token as his answer to money. He did it with sly goals in view, not least of which, after winning the trade, was to bind the customer more closely to his shop, a purpose which has lingered to our own day. "No doubt there were other reasons, too," muses Hamilton, a lean, handsome man, his closely cropped beard slightly frosted with gray. "The customer gains From the use of trade tokens, too, you must understand, or their use would never have lasted so long. He may secure the financial advantage of buying in quantity beyond his needs of the moment. A cigar store might sell its wares at a nickle apiece or six for a quarter. The customer could pay a quarter, select a couple and take four tokens change; he would have the cigars he needed, could get them at a lower rate, and the merchant could utilize the extra cash until the tokens were used up. "Or suppose a man developed a panic thirst. In a pre-inflation day he would buy a drink and hand the barkeep a quarter. The house man either gave him a dime change, or a token worth 1212 cents, half of the quarter. The customer accepted the token because that meant another drink when his thirst returned, while if he took a dime change it would have to be supplemented then by a nickle.Thus the token worked to the advantage of individuals on both sides of the counter, providing the customer really needed the drink, which would be a matter of opinion."

Tokens thus obtained naturally encouraged the man to remain and drink more at the saloon because he could trade them nowhere else and anyway he probably did not wish to take them home where his wife would find them when she searched for change in his pockets. If he had just been paid, and spent enough tokens in this way, he might become a saloon nuisance and get bounced, when he would stagger home through the darkness possibly losing, on his erratic course, what tokens he still possessed. This could benefit two parties, the saloon keeper who would never have to make them good, and some future token collector, who, discovering them, could add the items to his albums or trade them to someone else, all of this proving once again that the hoary adage about an ill wind might be a cliche, but it also is true.

Hamilton, at his rambling Tucson ranch home, exhibits a seemingly endless number of album pages with tokens of every variety neatly mounted upon them. He believes that their use may have originated from a shortage of cash, and he speaks with authority about coins. "I was very much into collecting them," he admits, "but I found that too much of my

(Right) In early day Arizona, the prosperity of mining towns was very much intertwined with railroads. An unprofitable claim could become worth a fortune with the availability of adequate rail service.

(Below) Ed Bertram owned several Tucson saloons around the turn of the century. The one pictured here is typical of such establishments of the time.

(Left) Because of its unusual shape, the Palace Saloon's token, bottom right in the photo, earned the nickname — “Palace Guitar Pick."

(Bottom) Marie LeLong was one of Tombstone's more prosperous brothel keepers, as this bank deposit for $730 shows. Records of 1881 reveal that Wyatt Earp was threatened with a suit for failing to turn in the fees he collected from several of the town's madams.

mainly ceased during the 1930s, although Indian traders continued to use them until the 1950s and might still, for all I know."

It is no simple matter to accurately date a trade token, but approximations can often be arrived at.

"Tokens usually were made of brass, a few from nickel, and many from aluminum," he says. "Aluminum was not commonly used until after 1893, so tokens of that metal would be later than that. If the token bears the legend, say, 'Joe's Pool Hall, Tombstone, A.T.' you know it was made before 1912, when Arizona became a state. But you have to watch for sharpies in this as in any other field. He adds, "I could write a book about the incredible lies people tell me: how they have a pot full of tokens morethan a hundred years old, when their legends show them to have been issued by concerns not in existence before 1910, say. All of which adds to the general enjoyment — providing the collector is not token-taken.

"The plagues of the collector are fakes and fantasies," he says, ruefully. "There also are counterfeits, or copies of tokens that actually existed. Luckily there are not many of these."

But "fantasies" are the product of lowlived characters who prey upon the lack of knowledge of the uninformed buyer. Many of these are dollar-sized brass discs, crudely made and crudely worded, frequently the product of crude humor or supposed-humor. They are turned out by the thousands. A rule of thumb might be that if the wordage on a token is “too good to be true,” it probably is not true. One revealing error the fantasy creators often make is to assume that the old-time Westerners were as crude of speech as we are. That was not often the case. A bawdily-worded token, you may be sure, is a baldly-worded phoney. Hamilton, emphasizing the prevalence of such fakery, says he has never seen a genuine token issued by a bordello — at least an Arizona bordello — although hehas run across countless fakes offering “an evening with Sadie,” or some similar delight, and this despite the articles and occasional books that build upon the supposed existence of the general family, if that be the word, of such slugs.

"Most of those I have seen were put out by some anonymous swindlers as gags," he recalls. "Of course there were plenty of saloon tokens not specifying what they were for, and most saloons were connected in some way with bawdy houses. There is no way to tell how the token should be spent. Maybe some were accepted by the house next door."

Some tokens in his collection pose mysteries that may border on this use. One was from the Red Light Saloon of Bisbee, but maybe a red light in that day did not mean what it does in modern times. Another, used by Sam Abraham's Clifton hotel and saloon, says it is “good for a hula hula at the Midway,” whatever that meant.

In the main the tokens were for very legitimate purchases. One in Hamilton's possession, somewhere between a nickle and a quarter in size and of scalloped edge, bears the legend on one side: “Goldwater's. The Best Always. Prescott, Ariz.,” and, on the reverse: “Good 712, 3313, or 40 cents, or $4 or $8. Many could be used for the purchase of a specific item, as in the Goldwater example. A token might be good for one drink, a cigar, a quart of milk, a loaf of bread. One in my collection could be traded for 50 pounds of ice, another for 'one heist,' which was a drink, or 'one smile,' a small whiskey bottle containing 21/2 ounces. Still another is good for a shave, one for a bath, and several are valued at one-bit, half of a quarter, or two-bits."

Maverick tokens are less desirable than others, a "maverick" being akin to an unbranded steer whose ownership is not clearly evident. "These are tokens that don't say where the business is located," Hamilton explains.

For many collectors, of course, the more bizarre the place the more desirable its token.

Hamilton himself would dearly love to obtain tokens from Ruby, Helvetia, Gunsight, Total Wreck, Quijotoa, Mascot, Galeyville, Red Rock, Rawhide, Tubac, American Flag or Bumble Bee, all honored in the state's history and legend.

Tokens from these places have never been found, to his knowledge, although his collection includes them from Paradise, next door to Galeyville, and from Wide Ruins, Wolf Post, Gold Bar, Gold Road and Gold Dust as well as Hopewell Tunnel, Kofa, Turkey, Octave, Joseph City, Copper Hill and Silverbell, Big Bug, Black Diamond, Crown King Cañon and even from Eden, although whether from the Garden of, is not stated.

"Wind, dust, termites and vandals have removed almost every trace of the existence of many former Arizona towns, and the token from some long-dead enterprise could be the only surviving relic," says Hamilton.

As with everything else, token prices have inflated within the past few years, but occasionally the price for examples from a given place will collapse if someone finds a lot of them. Oatman offers a clear instance. A few years ago tokens from Oatman were rare, only a couple of varieties being known. Because of its interesting history, from its 1902 founding through halcyon days of gold mining to its becoming the ghost town featured in the Cinerama spectacle, "How the West Was Won," the few tokens from Oatman were highly prized. But the place has been heavily dug, more than 25 kinds of Oatman trade tokens recovered, and their value as a consequence has plummeted.

That is one of the hazards a token trader must face, but since he probably doesn't have much of a capital investment in the first place, he can take such a debacle philosophically, if he is such a man as Hamilton.

A real estate broker and Pima County chairman of the Libertarian Party, Hamilton came by his hobby honestly, but it was kind of a serendipity. At Tombstone for another purpose, he came across a couple of tokens. These stirred his interest. One thing led to another. Collecting the interesting pieces became an avocation crowding out his pursuit of old coins, as we have seen, and even of political buttons, of which he has at least a thousand varieties.

In order to buy and trade he maintains contact with a national organization which ebbs and flows as interest in the hobby wanes and surges among its 400 or so members.

Nevada tokens are higher in average value than those of Arizona, perhaps because more people collect them. Arizona and California rank second and third; then come Colorado, New Mexico and Texas and after these other western states. But in any case their value is subjective. Most pieces probably are swapped from collector to collector and are never sold at all. Common tokens when they do come on the market ordinarily bring from $2 to $5, most are worth less than $10, and very few bring as much as $50.

"There are variables that determine the desirability of a particular token for me," Hamilton concludes, "but mostly how much I want it."

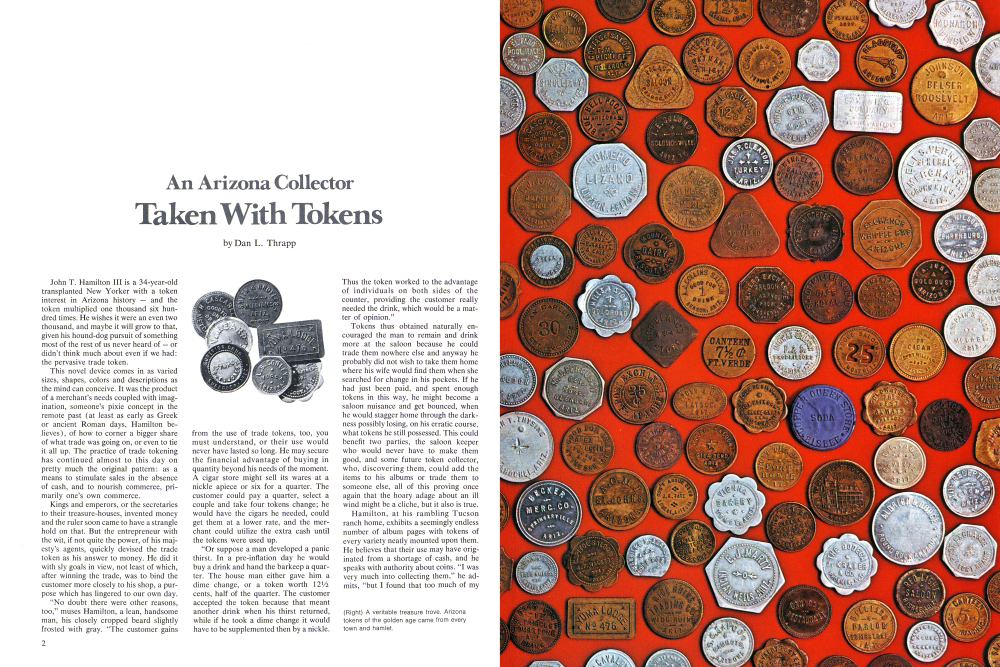

(Left) Token varieties were limited only by the imaginations of those who made them and the merchants who issued them.

(Below) A great many early merchants issued tokens, mostly for such "necessities" as drinks, cigars and bread.

Photographs by Gill Kenny

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We wish to acknowledge the following for their assistance in the production of Taken With Tokens: First National Bank, Lewis Douglas Memorial Office; Old Tucson; Arizona Historical Society; and Alberto Contreras and Sons, jewelers.

Already a member? Login ».