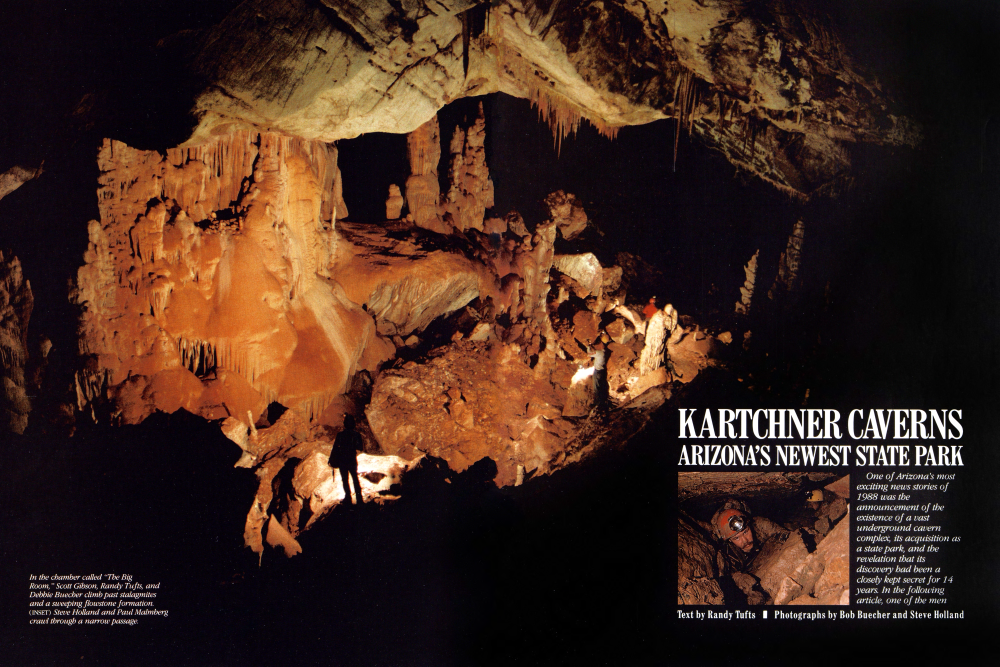

Kartchner Caverns: Arizona's Newest State Park

One of Arizona's most exciting news stories of 1988 was the announcement of the existence of a vast underground cavern complex, its acquisition as a state park, and the revelation that its discovery had been a closely kept secret for 14 years. In the following article, one of the men

who found "the cave" in 1974 tells Arizona Highways readers about that adventure and what the Kartchner Caverns are like. -The Editor The cave entrance is located in a rounded limestone hill that rests against the rough eastern edge of the Whetstone Mountains southwest of Benson, Arizona. Along the hill's southern flank curves a mesquite and oak woodland, watered by streams that run down from the mountains to empty into the San Pedro River. For hundreds of thousands of years these waters have percolated through the raw bedrock, dissolving the limestone and carving huge cavities decorated with splendid calcium carbonate formations, to create a masterpiece recently christened Kartchner Caverns.

Hiking in southeastern Arizona one day in 1974, Gary Tenen and I came upon a small opening I had first noticed in 1967. This time we contemplated the crevice among the boulders and decided to investigate.

Gary squeezed through first, somersaulting until he slid down a few feet of rock slope into a small room. I followed into what I recognized was a limestone solution cavity. It was dry and dusty, with foot-long stalactites descending from the ceiling, a slab of dirty flowstone, and a few footprints all typical of Arizona caves. Typically, too, the cave seemed to end right there. Then we saw a low crawlway that twisted back into darkness from one corner of the room, a tunnel from which we felt warm, damp air emerging.

Sandwiched between beds of limestone, we inched along, following the inviting breeze to a spot where the space opened a bit, only to narrow abruptly into an orifice a mere six inches across. There we lay, breaking the rock apart with an eightpound sledge, alternating positions when our arms tired. The flames of our carbide lamps danced in the swirling air. In two hours, the hole was large enough for Gary to slip through; in 10 more minutes I could follow.

Once beyond the blowhole, the glow from our lamps illuminated a dim corridor threading among projecting formations. Overhead, dripping stalactites hung from layers of tilted limestone. In the center of the room was a 10-foot-high rockpile, where dark strata arched into pitch darkness. There were no footprints. This was a virgin cave.

Carefully we traced a route next to the rubble. In a silent ballet, we gingerly stepped among the formations to avoid touching anything. (Fully a thousand years may be required for a single cubic inch of cave crystal to appear, yet the slightest touch can deposit skin oils that halt the growth.) At each branching or change in direction, we checked to make sure we could locate the return path.

Soon we came to a broad chamber where red calcite colored the wall and black portals stared from the distance. As if the scene might dissolve with the slightest break in our concentration, we sought to absorb every detail. Then, to comprehend our find more fully, we extinguished our lamps and sat silently in the darkness. After a while, we were aroused by the realization that no one knew where we were-a solemn thought for cave explorers. We relit our lamps, causing the surrounding stones to glow softly, and slowly we made our way out of the caverns for the first time.

realization that no one knew where we were-a solemn thought for cave explorers. We relit our lamps, causing the surrounding stones to glow softly, and slowly we made our way out of the caverns for the first time.

When Gary and I discovered the caverns that memorable day, we realized at once they were vulnerable to vandalism. Luckily, James and Lois Kartchner, owners of the land, understood the need for protection. They kept the caves' existence secret while we worked to arrange long-term care. The Arizona Nature Conservancy, functioning as an intermediary, aided the Arizona State Parks Board in acquiring the caverns on September 29, 1988, for $1,625,000, a $250,000 savings against the appraised value.

So far only a handful of people have visited both wings of the complex, and only Gary and I have explored all of it that is known. There is one entrance now, but others may have existed in the past. How else can we explain blocked sinkholes on the surface or the presence in a remote niche of the calcified bones of a bison?

Perhaps the bats know. Mysteriously, far back in one wing, there are eroded mounds of very old guano. Did bats at one time navigate a mile of complex passages or was there indeed another entrance? Through what vaulted chambers unknown to us did their flights carry them? Today in Kartchner Caverns, nature's magical artistry continues. A full 95 percent of the cave area is "alive," its formations still growing. Water, seeping as it has for countless ages through the limestone roof, continues to dissolve minute amounts of calcium carbonate. When the mineralized water emerges into the cavity, the sequence reverses and calcite crystallizes on any available surface. As droplets hang from the ceiling, trickle down the wall, or splash on the floor, they solidify in crystals that grow into sculptured formations called speleothems. The most familiar of these are the pointed stalactites and mounded stalagmites. These sometimes meet to form cylindrical columns.

This gradual, amazing process has produced a host of wonders, among them a column fully 50 feet in height and the color of redwood. It is the largest of its kind in Arizona. Here, too, are some of the longest "soda straw" stalactites, hanging breathlessly in the ancient stillness. One of them, a delicate tube onefourth inch in diameter and completely hollow, extends more than 20 feet!

Though evolved in eternal darkness, the cave colors are remarkably bold. Natural coloring agents derived from the rock or the soil have mingled with the calcite and imparted to the formations a spectrum of yellows and reds. Since every major type of speleothem is found in Kartchner Caverns, the combinations of geometry and hue seem to multiply endlessly. Trans-lucent curtains of rose and butterscotch ripple earthward in screens and draperies or eddy over the rocks as flowstone. Creamy helictites grow in branching defiance of gravity like rebellious fettucini. White "shields," heavy one-meter disks festooned with stalactites, take on the airiness of angel's wings.

All these natural features the State Parks Department intends to preserve. Specialists have already begun sampling the cave environment, seeking to avoid drying conditions, which would mean a loss of speleothem luster, and algae growth and accumulation of lint, which would bring about discoloration of the formations.

No final designs have been drawn as yet for the state park scheduled to open sometime in 1992. It is probable that there will be a visitors center with exhibits, nature trails, picnic areas, and some form of supervised cave tour. The nature of underground facilities is still open to conjecture as well. Much depends upon the scientific testing now going on. It is certain, however, that whatever tour is devised, it will provide visitors with a striking view of a fragile wonderland with minimal impact on the cave structure itself. Developing Kartchner Caverns State Park, preserving as well as displaying its natural marvels, will be a challenging and rewarding project. But the guiding principle should always be to ask ourselves, "What's best for the cave?"

Already a member? Login ».