Hike of the Month

HIKE OF THE MONTH Charlie Bell Pass Might Be Cruel Punishment for Novice Hikers, but the Wildlife and History Are Worth It

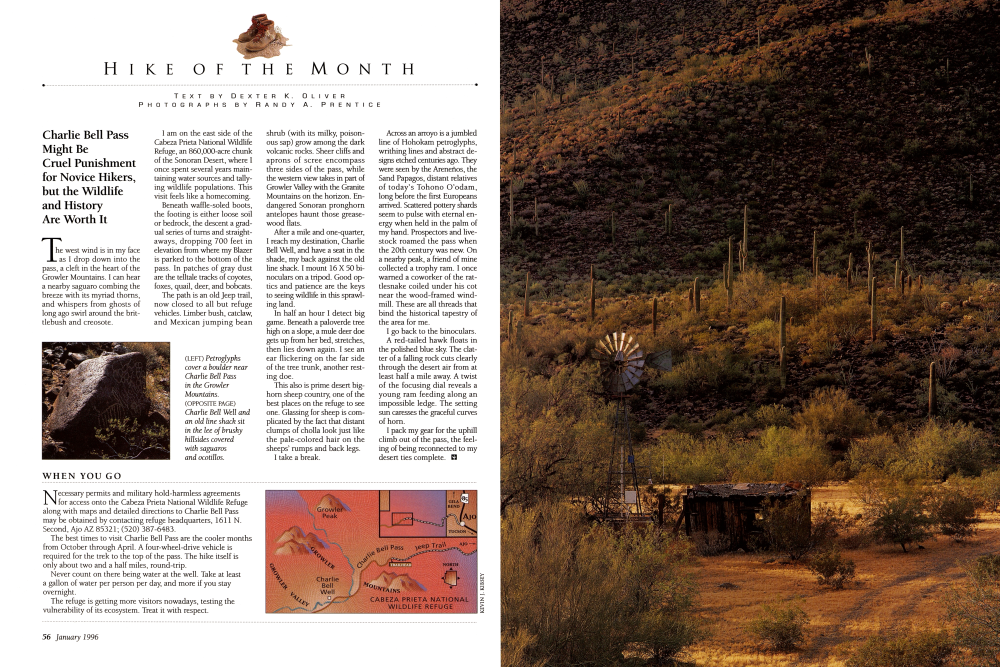

The west wind is in my face as I drop down into the pass, a cleft in the heart of the Growler Mountains. I can hear a nearby saguaro combing the breeze with its myriad thorns, and whispers from ghosts of long ago swirl around the brittlebush and creosote.

I am on the east side of the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, an 860,000-acre chunk of the Sonoran Desert, where I once spent several years maintaining water sources and tallying wildlife populations. This visit feels like a homecoming. Beneath waffle-soled boots, the footing is either loose soil or bedrock, the descent a gradual series of turns and straightaways, dropping 700 feet in elevation from where my Blazer is parked to the bottom of the pass. In patches of gray dust are the telltale tracks of coyotes, foxes, quail, deer, and bobcats. The path is an old Jeep trail, now closed to all but refuge vehicles. Limber bush, catclaw, and Mexican jumping bean shrub (with its milky, poisonous sap) grow among the dark volcanic rocks. Sheer cliffs and aprons of scree encompass three sides of the pass, while the western view takes in part of Growler Valley with the Granite Mountains on the horizon. Endangered Sonoran pronghorn antelopes haunt those greasewood flats.

After a mile and one-quarter, I reach my destination, Charlie Bell Well, and have a seat in the shade, my back against the old line shack. I mount 16 X 50 binoculars on a tripod. Good optics and patience are the keys to seeing wildlife in this sprawling land.

In half an hour I detect big game. Beneath a paloverde tree high on a slope, a mule deer doe gets up from her bed, stretches, then lies down again. I see an ear flickering on the far side of the tree trunk, another resting doe.

This also is prime desert bighorn sheep country, one of the best places on the refuge to see one. Glassing for sheep is complicated by the fact that distant clumps of cholla look just like the pale-colored hair on the sheeps' rumps and back legs. I take a break. Across an arroyo is a jumbled line of Hohokam petroglyphs, writhing lines and abstract designs etched centuries ago. They were seen by the Areneños, the Sand Papagos, distant relatives of today's Tohono O'odam, long before the first Europeans arrived. Scattered pottery shards seem to pulse with eternal energy when held in the palm of my hand. Prospectors and livestock roamed the pass when the 20th century was new. On a nearby peak, a friend of mine collected a trophy ram. I once warned a coworker of the rattlesnake coiled under his cot near the wood-framed windmill. These are all threads that bind the historical tapestry of the area for me.

I go back to the binoculars. A red-tailed hawk floats in the polished blue sky. The clatter of a falling rock cuts clearly through the desert air from at least half a mile away. A twist of the focusing dial reveals a young ram feeding along an impossible ledge. The setting sun caresses the graceful curves of horn. I pack my gear for the uphill climb out of the pass, the feeling of being reconnected to my desert ties complete.

WHEN YOU GO

Necessary permits and military hold-harmless agreements for access onto the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge along with maps and detailed directions to Charlie Bell Pass may be obtained by contacting refuge headquarters, 1611 N. Second, Ajo AZ 85321; (520) 387-6483.

The best times to visit Charlie Bell Pass are the cooler months from October through April. A four-wheel-drive vehicle is required for the trek to the top of the pass. The hike itself is only about two and a half miles, round-trip.

Never count on there being water at the well. Take at least a gallon of water per person per day, and more if you stay overnight.

The refuge is getting more visitors nowadays, testing the vulnerability of its ecosystem. Treat it with respect.

Already a member? Login ».