Back Road Adventure

Ghost Riding to Old Helvetia in the Santa Rita Mountains

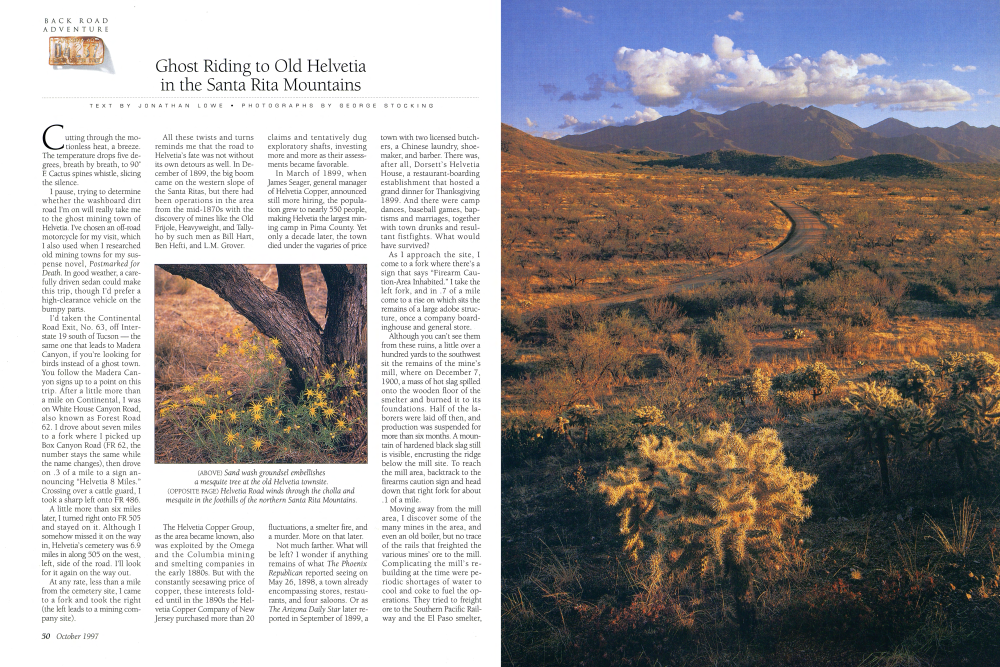

Cutting through the motionless heat, a breeze. The temperature drops five degrees, breath by breath, to 90° F. Cactus spines whistle, slicing the silence.

I pause, trying to determine whether the washboard dirt road I'm on will really take me to the ghost mining town of Helvetia. I've chosen an off-road motorcycle for my visit, which I also used when I researched old mining towns for my suspense novel, Postmarked for Death. In good weather, a carefully driven sedan could make this trip, though I'd prefer a high-clearance vehicle on the bumpy parts.

I'd taken the Continental Road Exit, No. 63, off Interstate 19 south of Tucson - the same one that leads to Madera Canyon, if you're looking for birds instead of a ghost town. You follow the Madera Canyon signs up to a point on this trip. After a little more than a mile on Continental, I was on White House Canyon Road, also known as Forest Road 62. I drove about seven miles to a fork where I picked up Box Canyon Road (FR 62, the number stays the same while the name changes), then drove on .3 of a mile to a sign announcing "Helvetia 8 Miles." Crossing over a cattle guard, I took a sharp left onto FR 486. A little more than six miles later, I turned right onto FR 505 and stayed on it. Although I somehow missed it on the way in, Helvetia's cemetery was 6.9 miles in along 505 on the west, left, side of the road. I'll look for it again on the way out.

At any rate, less than a mile from the cemetery site, I came to a fork and took the right (the left leads to a mining company site).

All these twists and turns reminds me that the road to Helvetia's fate was not without its own detours as well. In December of 1899, the big boom came on the western slope of the Santa Ritas, but there had been operations in the area from the mid-1870s with the discovery of mines like the Old Frijole, Heavyweight, and Tally-ho by such men as Bill Hart, Ben Hefti, and L.M. Grover.

claims and tentatively dug exploratory shafts, investing more and more as their assessments became favorable.

In March of 1899, when James Seager, general manager of Helvetia Copper, announced still more hiring, the population grew to nearly 550 people, making Helvetia the largest mining camp in Pima County. Yet only a decade later, the town died under the vagaries of price The Helvetia Copper Group, as the area became known, also was exploited by the Omega and the Columbia mining and smelting companies in the early 1880s. But with the constantly seesawing price of copper, these interests folded until in the 1890s the Helvetia Copper Company of New Jersey purchased more than 20 fluctuations, a smelter fire, and a murder. More on that later.

Not much farther. What will be left? I wonder if anything remains of what The Phoenix Republican reported seeing on May 26, 1898, a town already encompassing stores, restaurants, and four saloons. Or as The Arizona Daily Star later re-ported in September of 1899, a town with two licensed butchers, a Chinese laundry, shoemaker, and barber. There was, after all, Dorsett's Helvetia House, a restaurant-boarding establishment that hosted a grand dinner for Thanksgiving 1899. And there were camp dances, baseball games, baptisms and marriages, together with town drunks and resultant fistfights. What would have survived?

As I approach the site, I come to a fork where there's a sign that says "Firearm Cau-tion-Area Inhabited." I take the left fork, and in .7 of a mile come to a rise on which sits the remains of a large adobe struc-ture, once a company board-inghouse and general store.

Although you can't see them from these ruins, a little over a hundred yards to the southwest sit the remains of the mine's mill, where on December 7, 1900, a mass of hot slag spilled onto the wooden floor of the smelter and burned it to its foundations. Half of the laborers were laid off then, and production was suspended for more than six months. A moun-tain of hardened black slag still is visible, encrusting the ridge below the mill site. To reach the mill area, backtrack to the firearms caution sign and head down that right fork for about .1 of a mile.

Moving away from the mill area, I discover some of the many mines in the area, and even an old boiler, but no trace of the rails that freighted the various mines' ore to the mill. Complicating the mill's re-building at the time were pe-riodic shortages of water to cool and coke to fuel the op-erations. They tried to freight ore to the Southern Pacific Rail-way and the El Paso smelter,

but it was a losing proposition. When copper prices dipped again, Helvetia Copper went under, and still another chapter in the town's on again-off again history was ended.

Amid the scattered foundations, I find that only the one building's crumbling adobe walls stand out as a reminder that there once was a large assortment of buildings, tents, and shanties here. But then ghost town exploration is like that, and it demands imagination, even with old photos handy. There is never much left of buildings but rubble, although with the mind's eye and a little orientation, it may not be necessary to ask for help from a passing coyote.

Still, the few tourists who visit Helvetia end up staring at these same surviving walls as if at Stonehenge.

Oscar Buckalew had entered the stage and freighting business in the 1860s and became one of many entrepreneurs who later succeeded in latching onto Helvetia's runaway growth. As The Tucson Citizen put it at the time, “The Buckalew stages go the most direct route to Helvetia Mining Camp. This is the best equipped stage going out of Tucson.” Without a railroad to Tucson, Buckalew's business was good, but his luck was not. His life ended on April 17, 1910, when he was shot to death by an assailant seen fleeing on horseback from the freighter's home in Helvetia. And the murder was never solved.

Florence Cowan, Helvetia's first teacher, presided over some 100 pupils in the same year that Charles Coon was appointed first postmaster. The school survived even after 1910, but by then, even with renewed investments by companies such as Omega Copper, the mines could not be made profitable. By 1911 the mines were closed and the machinery sold. Gradually the few remaining mostly Mexican families deserted the townsite for Greaterville to the east, and Helvetia was ghosted into history.

After a solemn look around the townsite, I head back out looking for the cemetery I'd missed on the way in. It's got to be here somewhere.

Flowers placed on some of the graves stand out in the desert foliage and help me find the cemetery beside the road. There are about 30 graves, but most are as I thought they would be, covered simply with weathered wooden crosses. There's a section of tiny graves beneath a massive shade-giving mesquite tree.

I look up from this quiet place at those distant Santa Ritas, which serve as a backdrop to Tucson's southern side and now contain the recreation area and hummingbird habitat of Madera Canyon, when suddenly the thought strikes me that a hundred years ago Oscar Buckalew might have stood next to a grave here, too, and wondered what all this would look like a century later.

Back to the future, then, I climb on my iron horse, and ride on.

TIPS FOR TRAVELERS

Good maps to take on the trip are the Helvetia, Arizona, SE14 Sahuarita 15' Quadrangle and the Coronado National Forest map that includes the Santa Rita Mountains. Back road travel can be hazardous if you are not prepared for the unexpected. Whether traveling in the desert or in the high country, be aware of weather and road conditions and make sure you and your vehicle are in top shape and you have plenty of water. Don't travel alone, and let someone at home know where you're going and when you plan to return. Odometer readings in the story may vary by vehicle.

Already a member? Login ».