In Hopi Land

In Hopi Land The Snake Dance is Not a Prayer for Rain Pueblo Tribe Has a Ritual for Nearly Every Act of Living

ON the high wind-swept mesas of Hopi land in Northern Arizona, the serpent, most despised and unclean of reptiles in the minds of nearly all the peoples of the world, comes into its own this month. It is the time for the ceremony of the Snake Dance, and the tribesmen assemble at Walpi to appease their gods and offer up prayers of thanksgiving for the bounties of the season and the general welfare of the people.

Many whites will be there "to see the show", most awe inspiring of all the Indian religious rituals, and nearly all of them will come away not knowing what they have seen or appreciating its significance. For the Hopi has been badly treated both in spoken story and in printed tome.

Despite accepted versions, the Snake Dance ceremony is not a prayer for rain. Neither is it a fete or a fiesta. It is the expression of a beautiful symbolic religion, and to the Hopi it is a rather distasteful task which must be carefully and exactly performed from season to season as a tribute to the gods. A slip or an impurity will incur wrath and bring misery upon the nation. With the Hopi all is divinity. He plants his grain with a prayer-stick. There is a ritual for sowing and for growing and for nearly every act of living. He is probably the most devout of all the Indian races.

The Hopi, like the Christian, has his tradition of a Deluge. The tribesmen, through eras of ease and plenty, had grown sinful and wanton and had turned their faces from their gods. The gods, thus ignored and renounced, became angry and sent a great flood to punish them for their wickedness. Canyons filled with water, maize fields were inundated, homes were submerged, flocks were drowned and stores of provender were swept away. The people were forced to flee into the hills, and in widely scattered groups wandered over the face of the earth in search of such sustenance as had escaped the ravages of the waters. Time passed, generation succeeded generation, and finally the survivors of the deluge gradually drifted together until there were 21 clans, each with its own religion, legends and customs.

One of these was the Bear Clan, which had established itself in what is now the Hopi country of Arizona. Word spread among the peoples that this group, which through its trials and afflictions had evolved a powerfulsystem of religion, was again living in peace and happiness and in the favor of the gods. So the clans came gathering in from south and east and west to take up a new abode, seek forgiveness for the sins of their fathers and to participate in the munificence of the good spirits. Here the legend, which has been communicated from mouth to mouth down through the ages, varies a little between Walpi and Hotevilla. The lat ter version has it that during the mi gration of the tribes there was an oc currence in one group which was to have a far-reaching effect upon the people and establish a new religion.

It is recounted that there was a young and comely daughter of a chieftain. She was attractive and was wooed by many men, but she would have none of them. She spoke but seldom, did not partici pate in the activities of her fellows, and impressed them by her oddity and apparent preoccupation and air of mel oncholia. There came a day during the long journey into the sand wastes when this listless maiden fell behind and disap peared from the caravan. Her brother set out to seek her, turning backward many miles along the hot and tortur ous trail. He found her seated beneath the branches of a desert bush, well but prepossessed. Her answers to ques tions were evasive, and she told him she would go no farther, insisting that he leave her and rejoin the clan.

"I must stay here," she said, "here with my children."

"But you have no children."

"I have!" she exclaimed. "See, here they are."

And rising, she revealed in her place beneath the bush a number of serpents. "You must go on, my brother, and rejoin our people. I shall stay and care for my children. Once in each year, when the summer sun begins to decline, pay homage to them. For they are good, and they will be near the Spirit of the Underground Waters."

The brother went sorrowfully away, the sister remaining with her charges. And so the Snake people came into being, to carry out the command of the maiden, and each year for nine days in the Hopi villages the tribemen continue to pay homage to the serpent.

In the Walpi legend, parentage of the snakes is attributed to the wife of a young Indian, who in consequence is driven from the village into the desert by her people. Misery subsequently falls upon the tribe, which eventually is restored to happiness through the in tercession of the Snake fraternity.

The dance is enacted at Hotevilla and Walpi in alternate years, and at each place the local tradition is followed.

The first eight days of the ceremony are given over to preparing parapher nalia, making prayer-sticks and sand paintings, to chants and secret rites in the kiva, or communal ceremonial cham ber, and to collecting snakes. Parties of the Snake people on each of four days search the surrounding mesas for reptiles, and there is no choice of var iety. Rattlers and bull snakes, ven omous or harmless, it is all the same to the Hopi. He takes them as they come and has no fear of them. They are all descended from those which the Indian maiden mothered. If he is bit ten, it is because he has incurred the displeasure of the gods, and if he dies it is because the gods so will it. But he seldom dies.

When a sufficient number of snakes has been gathered they are taken into the depths of the kiva, where they are cleansed and blessed and made ready for the ceremony, treated as sacred things.

At sundown on the evening of the ninth day, the Snake Dance proper be gins, with the writhing serpents play ing a principal role. The ceremony completed, the dancers bearing hands ful of reptiles scurry back out on the mesas to return the "little messengers of the Spirit of the Underground Wat ers" to the place from whence they came, to carry back word that they have been blessed and sanctified and honored by the priests of the Snake people, that the command of the celestial maiden again has been obeyed and that the Hopi are deserving of ample rainfall, bounti ful harvests of maize and beans and the blessing and protection of whatever gods there be.

The katchena dances, ceremonials of the Katchena Clan, are more properly a prayer for rain, because it is nearly always rain that is asked of the Great Spirit. The Katchenas, the Hopi tell you, are the souls of aged and sagacious priests. Through the fall and winter

AUGUST, 1933 ARIZONA HIGHWAYS 5

They dwell on San Fancisco Peaks, near Flagstaff. Near the first of the year they descend to the mesas of their people where they take the guise of fairies to all and of Santa Claus to the children.

A katchena dance may take place at any time the priests so will it, but one always precedes the return of the Katchenas to their mountain abode as the autumn season approaches.

Many whites who are familiar with the Hopi country will tell you that whenever a rain prayer is included in the katchena ritual, rain nearly always falls within the next 24 hours.

The Hopi are a people of many legends, perhaps more than any other tribe. Tradition surrounds every locality, every water hole and every peculiar formation of rock or hill.

In the shadow of the cliff forming the mesa near Shipolovi stands a tall pillar of sandstone, the Corn Rock of the Hopi, now split down the center more than half its height. Originally, the Indian tells you, there were two pillars rising side by side. One fell at the time of the occupation by the Conquistadores of Spain under Coronado in the Seventeenth Century, when the Indians were bound in slavery until released by general uprising in 1680. Legend has it that the end will come to the Hopi people when the second pillar falls.

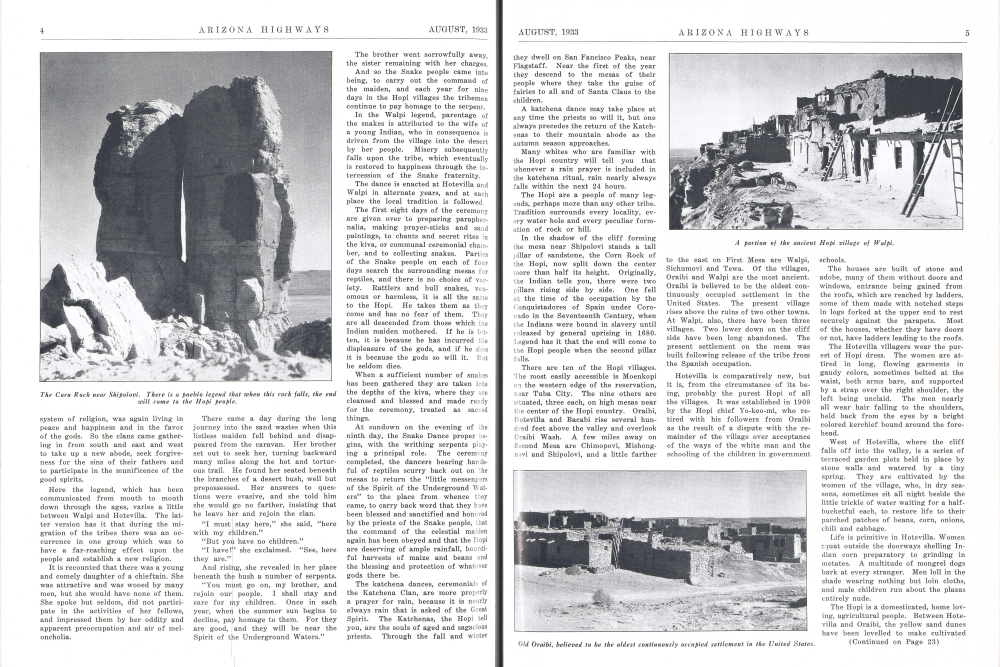

There are ten of the Hopi villages. The most easily accessible is Moenkopi on the western edge of the reservation, near Tuba City. The nine others are situated, three each, on high mesas near the center of the Hopi country. Oraibi, Hotevilla and Bacabi rise several hundred feet above the valley and overlook Oraibi Wash. A few miles away on Second Mesa are Chimopovi, Mishongnovi and Shipolovi, and a little farther to the east on First Mesa are Walpi, Sichumovi and Tewa. Of the villages, Oraibi and Walpi are the most ancient. Oraibi is believed to be the oldest continuously occupied settlement in the United States. The present village rises above the ruins of two other towns. At Walpi, also, there have been three villages. Two lower down on the cliff side have been long abandoned. The present settlement on the mesa was built following release of the tribe from the Spanish occupation.

Hotevilla is comparatively new, but it is, from the circumstance of its being, probably the purest Hopi of all the villages. It was established in 1908 by the Hopi chief Yo-keo-mi, who retired with his followers from Oraibi as the result of a dispute with the remainder of the village over acceptance of the ways of the white man and the schooling of the children in government schools. The houses are built of stone and adobe, many of them without doors and windows, entrance being gained from the roofs, which are reached by ladders, some of them made with notched steps in logs forked at the upper end to rest securely against the parapets. Most of the houses, whether they have doors or not, have ladders leading to the roofs.

The Hotevilla villagers wear the purest of Hopi dress. The women are attired in long, flowing garments in gaudy colors, sometimes belted at the waist, both arms bare, and supported by a strap over the right shoulder, the left being unclaid. The men nearly all wear hair falling to the shoulders, held back from the eyes by a bright colored kerchief bound around the forehead.

West of Hotevilla, where the cliff falls off into the valley, is a series of terraced garden plots held in place by stone walls and watered by a tiny spring. They are cultivated by the women of the village, who, in dry seasons, sometimes sit all night beside the little trickle of water waiting for a halfbucketful each, to restore life to their parched patches of beans, corn, onions, chili and cabbage.Life is primitive in Hotevilla. Women squat outside the doorways shelling Indian corn preparatory to grinding in metates. A multitude of mongrel dogs bark at every stranger. Men loll in the shade wearing nothing but loin cloths, and male children run about the plazas entirely nude.

The Hopi is a domesticated, home loving, agricultural people. Between Hotevilla and Oraibi, the yellow sand dunes have been levelled to make cultivated(Continued on Page 23)

Already a member? Login ».