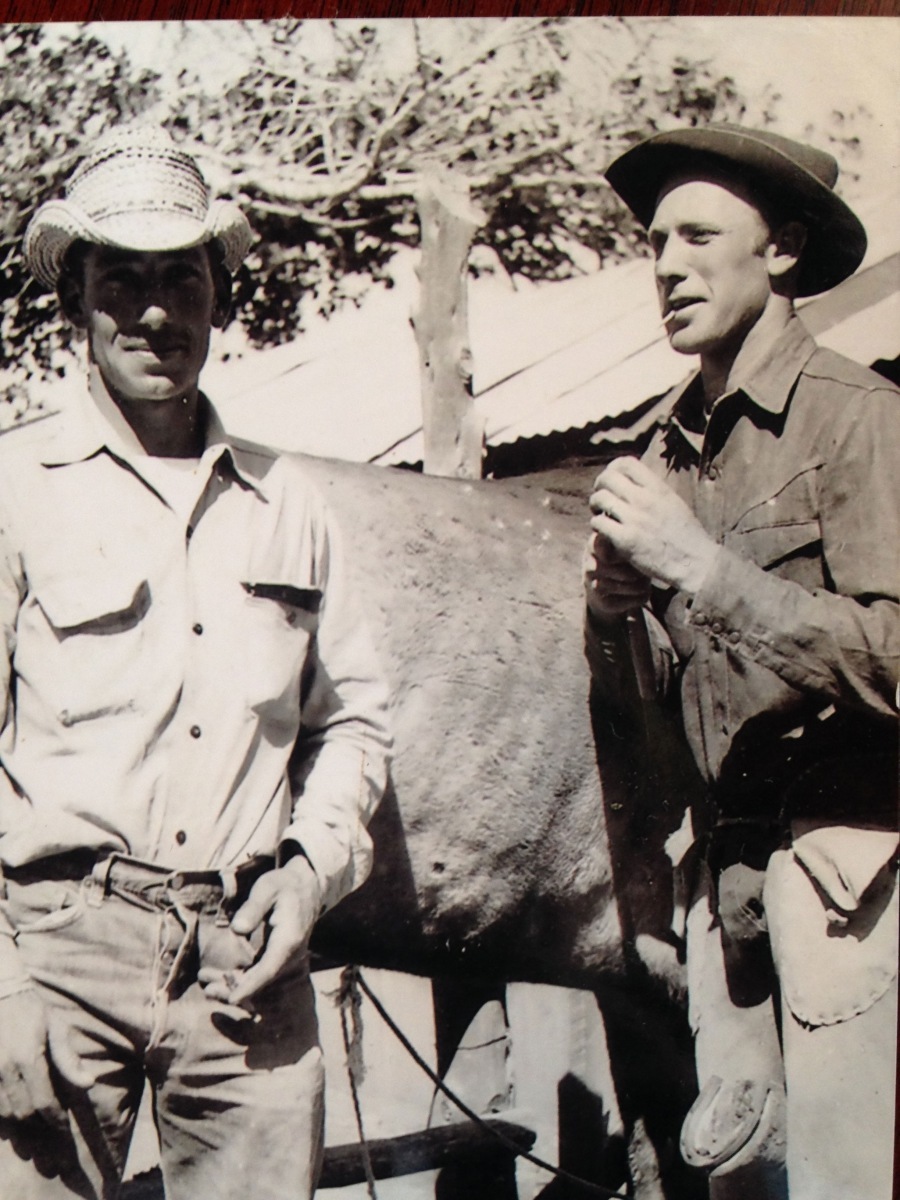

Above: Bruce McDonald (center) and Oran Ortleib, who worked at a ranch hand under McDonald at Orme Ranch, at McDonald's birthday party last month. Below: McDonald (right) and Frank Dandrea in their ranching days. | Courtesy of Jessica Calmes (2)

Bruce McDonald had his birthday party on September 28. What makes McDonald’s birthday stand out is that he turned 89 years old — and he’s from one of the longest-running Arizona ranch families. McDonald himself grew up ranching, roping horses and farming. “At this age, I’m really not too busy,” he says. “I keep my lots clean with a hoe, and I’m a different kind of a cat.”

A lot has changed in the days since McDonald’s youth. He took the time to talk to Arizona Highways about his history and the way Arizona has changed over the years.

You've been called one of the “last true Arizona cowboys.” Can you tell us about that?

You've been called one of the “last true Arizona cowboys.” Can you tell us about that?

Well, I worked 38 years for Orme Ranch and ran the outside. And I was roping horses in this country here when I was 13 years old. So, I mean, I hate to be the oldest, because my friends are all gone.

What was it like growing up a cowboy in Arizona?

I was lucky because I was working for some of the best people in the world, and they let me do what I should, no interference. I also, you know, they had a lot of kids there, and I had a 4-H Club, I had two roping clubs, and it was a good life. I couldn’t complain about anything that happened when I was there. I was there 38 years.

Who were you working with there? Was it a family?

Well, I worked with the family, the Ormes, and when they passed away I worked with their oldest son, and I worked some with their youngest son when he came back from the Marines. It was a real — the people I worked with were really great people. I have no complaints at all.

What sorts of things did you do?

I ran a dairy, and I supplied help with the horses for the ranch, and I broke horses, I put shoes on horses, I farmed and I butchered a lot of animals; I was a pretty good butcher. So, I had plenty to do. I worked seven days a week; I had a brother in Camp Verde, and I used to go over there. I worked with him one day a week. It was a good life.

Tell us a little bit about your family’s history.

Well, my grandfather come here in 1867, when he was 6 years old; him and Fred Dugas come in here on the same wagon train. I wandered around with him a little as a kid, but he died when I was about 8 years old, and he was deputy sheriff and livestock inspector and mayor for Yavapai County, and when he passed away my dad took over the job for another 35 years. My family couldn’t have been better. I don’t know how they could have been. There was no friction.

What was it like growing up in a family like yours, that had such history?

Well, I was the oldest, so I got to do a lot more work than the younger ones. I used to pack water. We didn’t have water in the house, hot water, so I’d build the fire and pack water to the washtub outside, and when it got hot I’d pack it inside to the washing machine, and noon when I came home from school I’d pack it out and pour it on the trees. It was a full life.

What changes have you seen over the years?

When I was in the service I crossed the United States four times, and I was in probably five different camps. In World War II, I was one that I’d go from one camp to another, and I worked with both German prisoners and American prisoners that were AWOLs and so forth. So, in the service, I went over to Liverpool, England. I saw the White Cliffs of Dover, and I saw the English Channel, though it was not moving at all. Went on down to the harbor of France, stayed there for a little while and come home. I came back home to New York City, and it’s quite a thing to see that statue in the harbor. I used to haul prisoners — I was stationed there at Fort Dixon — I used to haul prisoners down the Hudson River, where that airplane landed sometime back. I’ll tell you, it was something that most people never have.

One thing that’s different about what I have been, I’ve bought a home, I’ve got four kids. I’ve bought six homes all together, and I have never had a dime’s credit. Never. Each time I bought something, I paid for it. My dad always told me that I couldn’t afford 15 percent more than it was worth. So, I’ve had good supervision.

I mean, I knew every rancher within 30 miles of here. I rode horses all over everything within almost 30 miles of here. It was a busy life, but I enjoyed it.

What’s your most vivid memory of Arizona from when you were young, and how is it different today?

It is so different, it’s almost indescribable. Because in Mayer we used to have chickens and turkeys and milk cows and maybe a horse, and we rode a lot of burros. At that time there were no fences, and we used to ride burros a lot. We’d go 7 or 8 miles when I was 7 or 8 years old on burros, no supervision. Folks didn’t have to worry about us like they do today. The people were a better people as a whole.

Why would you say this history, your history and the history of ranching in Arizona, is important?

I’ve watched, and I have watched the government encroachment, and it is a sick world. Because where we used to raise cattle, the Forest Service has taken them all. They’ve made parks out of some of them. I mean, we don’t have any control — we’re just there to listen. It’s sad.

— Molly Bilker