SPANISH OCCUPATION INFLUENCED ARIZONA'S CULTURE

Spanish Occupation Influenced Arizona's IN THE YEAR 1540

IT IS the year of our Lord 1540. Arizona, the unknown and unnamed, will soon be entered in the great Jour-nal of History. The moving finger of Time prepares to write the first sentence of its colorful story.

You and I turn back the musty pages and read of the world in which lived those stalwart adventurers who blazed the first trails into the strange lands of the American Southwest. Aboard our imaginations we journey back to the Sixteenth century, the cen-tury of discovery and exploration, of the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation.

It is a fascinating period in which we find ourselves. Before us lies Spain, the brightest jewel in the dia-dem of nations, the mistress of the world and the queen of the oceans, the proud and arrogant possessor of the New World from which flows a steady stream of gold to enrich the coffers of the Holy Roman Emperor and Spanish King, Charles V. Insufficient, however, is all the gold of the

(Continued on Page 17)

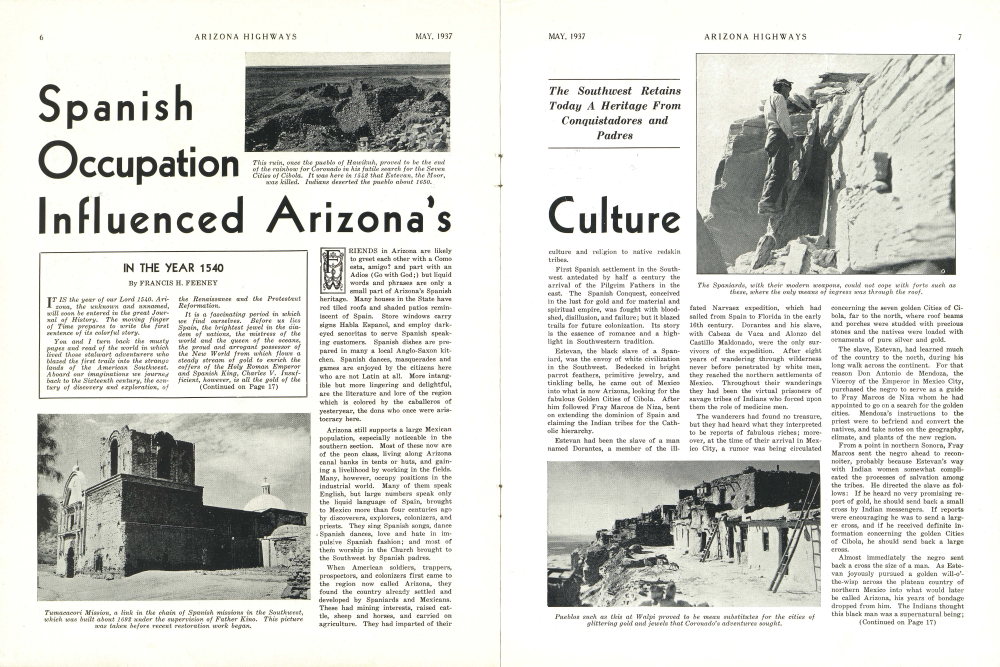

FRIENDS in Arizona are likely to greet each other with a Como esta, amigo? and part with an Adios (Go with God;) but liquid words and phrases are only a small part of Arizona's Spanish heritage. Many houses in the State have red tiled roofs and shaded patios reminiscent of Spain. Store windows carry signs Habla Espanol, and employ darkeyed senoritas to serve Spanish speaking customers. Spanish dishes are prepared in many a local Anglo-Saxon kitchen. Spanish dances, masquerades and games are enjoyed by the citizens here who are not Latin at all. More intangible but more lingering and delightful, are the literature and lore of the region which is colored by the caballeros of yesteryear, the dons who once were aristocracy here.

Arizona still supports a large Mexican population, especially noticeable in the southern section. Most of these now are of the peon class, living along Arizona canal banks in tents or huts, and gaining a livelihood by working in the fields. Many, however, occupy positions in the industrial world. Many of them speak English, but large numbers speak only the liquid language of Spain, brought to Mexico more than four centuries ago by discoverers, explorers, colonizers, and priests. They sing Spanish songs, dance Spanish dances, love and hate in impulsive Spanish fashion; and most of them worship in the Church brought to the Southwest by Spanish padres.

When American soldiers, trappers, prospectors, and colonizers first came to the region now called Arizona, they found the country already settled and developed by Spaniards and Mexicans. These had mining interests, raised cattle, sheep and horses, and carried on agriculture. They had imparted of theirculture and religion to native redskin tribes.

The Southwest Retains Today A Heritage From Conquistadores and Padres Culture

First Spanish settlement in the Southwest antedated by half a century the arrival of the Pilgrim Fathers in the east. The Spanish Conquest, conceived in the lust for gold and for material and spiritual empire, was fought with bloodshed, disillusion, and failure; but it blazed trails for future colonization. Its story is the essence of romance and a high light in Southwestern tradition.

Estevan, the black slave of a Spaniard, was the envoy of white civilization in the Southwest. Bedecked in bright parrot feathers, primitive jewelry, and tinkling bells, he came out of Mexico into what is now Arizona, looking for the fabulous Golden Cities of Cibola. After him followed Fray Marcos de Niza, bent on extending the dominion of Spain and claiming the Indian tribes for the Catholic hierarchy.

Estevan had been the slave of a man named Dorantes, a member of the ill-fated Narvaez expedition, which had sailed from Spain to Florida in the early 16th century. Dorantes and his slave, with Cabeza de Vaca and Alonzo del Castillo Maldonado, were the only survivors of the expedition. After eight years of wandering through wilderness never before penetrated by white men, they reached the northern settlements of Mexico. Throughout their wanderings they had been the virtual prisoners of savage tribes of Indians who forced upon them the role of medicine men.

fated Narvaez expedition, which had sailed from Spain to Florida in the early 16th century. Dorantes and his slave, with Cabeza de Vaca and Alonzo del Castillo Maldonado, were the only survivors of the expedition. After eight years of wandering through wilderness never before penetrated by white men, they reached the northern settlements of Mexico. Throughout their wanderings they had been the virtual prisoners of savage tribes of Indians who forced upon them the role of medicine men.

The wanderers had found no treasure, but they had heard what they interpreted to be reports of fabulous riches; moreover, at the time of their arrival in Mexico City, a rumor was being circulated concerning the seven golden Cities of Cibola, far to the north, where roof beams and porches were studded with precious stones and the natives were loaded with ornaments of pure silver and gold.

concerning the seven golden Cities of Cibola, far to the north, where roof beams and porches were studded with precious stones and the natives were loaded with ornaments of pure silver and gold.

The slave, Estevan, had learned much of the country to the north, during his long walk across the continent. For that reason Don Antonio de Mendoza, the Viceroy of the Emperor in Mexico City, purchased the negro to serve as a guide to Fray Marcos de Niza whom he had appointed to go on a search for the golden cities. Mendoza's instructions to the priest were to befriend and convert the natives, and take notes on the geography, climate, and plants of the new region.

From a point in northern Sonora, Fray Marcos sent the negro ahead to reconnoiter, probably because Estevan's way with Indian women somewhat complicated the processes of salvation among the tribes. He directed the slave as follows: If he heard no very promising report of gold, he should send back a small cross by Indian messengers. If reports were encouraging he was to send a larger cross, and if he received definite information concerning the golden Cities of Cibola, he should send back a large cross. Almost immediately the negro sent back a cross the size of a man. As Estevan joyously pursued a golden will-o'the-wisp across the plateau country of northern Mexico into what would later be called Arizona, his years of bondage dropped from him. The Indians thought this black man was a supernatural being;

Already a member? Login ».