THE AMERIND FOUNDATION

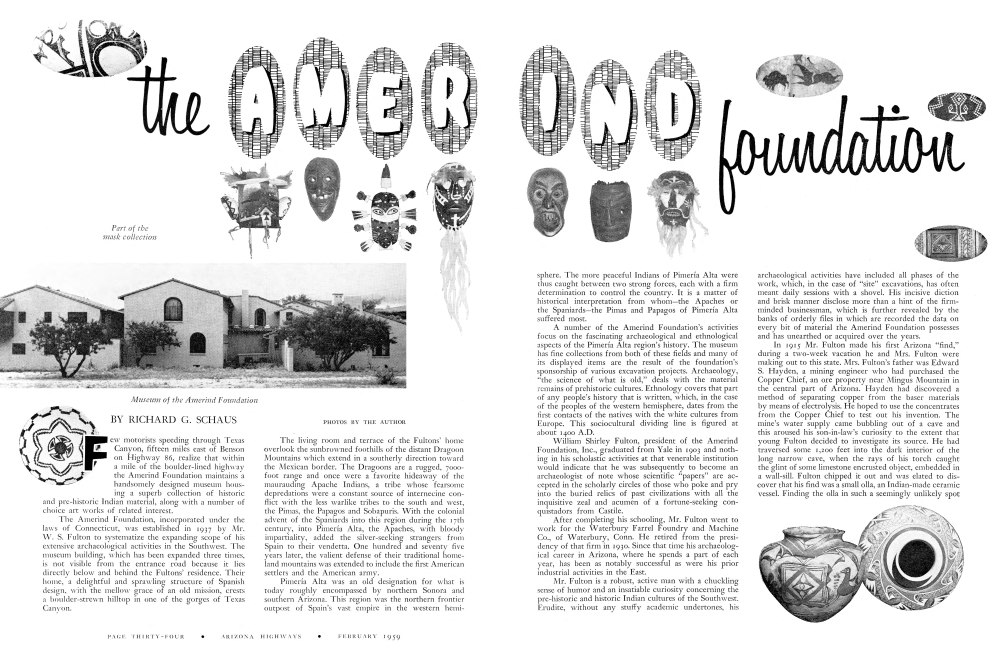

Few motorists speeding through Texas Canyon, fifteen miles east of Benson on Highway 86, realize that within a mile of the boulder-lined highway the Amerind Foundation maintains a handsomely designed museum hous-ing a superb collection of historic and pre-historic Indian material, along with a number of choice art works of related interest.

The Amerind Foundation, incorporated under the laws of Connecticut, was established in 1937 by Mr. W. S. Fulton to systematize the expanding scope of his extensive archaeological activities in the Southwest. The museum building, which has been expanded three times, is not visible from the entrance road because it lies directly below and behind the Fultons' residence. Their home, a delightful and sprawling structure of Spanish design, with the mellow grace of an old mission, crests a boulder-strewn hilltop in one of the gorges of Texas Canyon.

PHOTOS BY THE AUTHOR

The living room and terrace of the Fultons' home overlook the sunbrowned foothills of the distant Dragoon Mountains which extend in a southerly direction toward the Mexican border. The Dragoons are a rugged, 7000foot range and once were a favorite hideaway of the maurauding Apache Indians, a tribe whose fearsome depredations were a constant source of internecine conflict with the less warlike tribes to the south and west, the Pimas, the Papagos and Sobapuris. With the colonial advent of the Spaniards into this region during the 17th century, into Pimería Alta, the Apaches, with bloody impartiality, added the silver-seeking strangers from Spain to their vendetta. One hundred and seventy five years later, the valiant defense of their traditional homeland mountains was extended to include the first American settlers and the American army.

Pimería Alta was an old designation for what is today roughly encompassed by northern Sonora and southern Arizona. This region was the northern frontier outpost of Spain's vast empire in the western hemi-sphere. The more peaceful Indians of Pimería Alta were thus caught between two strong forces, each with a firm determination to control the country. It is a matter of historical interpretation from whom the Apaches or the Spaniards-the Pimas and Papagos of Pimería Alta suffered most.

000 foundation

sphere. The more peaceful Indians of Pimería Alta were thus caught between two strong forces, each with a firm determination to control the country. It is a matter of historical interpretation from whom the Apaches or the Spaniards-the Pimas and Papagos of Pimería Alta suffered most.

A number of the Amerind Foundation's activities focus on the fascinating archaeological and ethnological aspects of the Pimería Alta region's history. The museum has fine collections from both of these fields and many of its displayed items are the result of the foundation's sponsorship of various excavation projects. Archaeology, "the science of what is old," deals with the material remains of prehistoric cultures. Ethnology covers that part of any people's history that is written, which, in the case of the peoples of the western hemisphere, dates from the first contacts of the natives with the white cultures from Europe. This sociocultural dividing line is figured at about 1400 A.D.

William Shirley Fulton, president of the Amerind Foundation, Inc., graduated from Yale in 1903 and nothing in his scholastic activities at that venerable institution would indicate that he was subsequently to become an archaeologist of note whose scientific "papers" are accepted in the scholarly circles of those who poke and pry into the buried relics of past civilizations with all the inquisitive zeal and acumen of a fortune-seeking conquistadors from Castile.

After completing his schooling, Mr. Fulton went to work for the Waterbury Farrel Foundry and Machine Co., of Waterbury, Conn. He retired from the presidency of that firm in 1930. Since that time his archaeological career in Arizona, where he spends a part of each year, has been as notably successful as were his prior industrial activities in the East.

Mr. Fulton is a robust, active man with a chuckling sense of humor and an insatiable curiosity concerning the pre-historic and historic Indian cultures of the Southwest. Erudite, without any stuffy academic undertones, his archaeological activities have included all phases of the work, which, in the case of "site" excavations, has often meant daily sessions with a shovel. His incisive diction and brisk manner disclose more than a hint of the firmminded businessman, which is further revealed by the banks of orderly files in which are recorded the data on every bit of material the Amerind Foundation possesses and has unearthed or acquired over the years.

In 1915 Mr. Fulton made his first Arizona "find," during a two-week vacation he and Mrs. Fulton were making out to this state. Mrs. Fulton's father was Edward S. Hayden, a mining engineer who had purchased the Copper Chief, an ore property near Mingus Mountain in the central part of Arizona. Hayden had discovered a method of separating copper from the baser materials by means of electrolysis. He hoped to use the concentrates from the Copper Chief to test out his invention. The mine's water supply came bubbling out of a cave and this aroused his son-in-law's curiosity to the extent that young Fulton decided to investigate its source. He had traversed some 1,200 feet into the dark interior of the long narrow cave, when the rays of his torch caught the glint of some limestone encrusted object, embedded in a wall-sill. Fulton chipped it out and was elated to discover that his find was a small olla, an Indian-made ceramic vessel. Finding the olla in such a seemingly unlikely spot whetted his interest in archaeological matters. On subsequent annual vacations to Arizona, Mr. Fulton was to make other discoveries on trips to the then seldom-visited sections of the Navajo and Hopi country in northern Arizona.

It was on these vacation expeditions to the wild, starkly forlorn country of the north that he began collecting ethnological material that today are an important and select part of the Amerind Museum's superb collections-heavy silver concho belts of exquisite workmanship, numerous other pawn articles, genuine Hopi Katchinas painted in gay colors, Hopi prayer rugs and Navajo blankets of splendid design and color. All "pre-tourist."

These items were acquired over the years on various planned trips Mr. Fulton would make, such as one expedition that was instigated to locate the headwaters of Canyon de Chelly. This lordly and spectacular canyon is in a region of the vast Navajo country that was little known and seldom visited at that time. A trip through and beyond this gorge was indeed an exploration, even with native guides along.

It was during such a trip as this, on his 1925 vacation, that Mr. Fulton and a friend, along with a guide, stumbled across a cave, the walls of which were profusely decorated with Indian pictographs. all in vivid colors. The exploring vacationeers promptly named the site "Painted Cave." Further investigation suggested that they had located a rich archaeological site. Pottery sherds, a fine Indian basket and other artifacts indicated that the site had been the prehistoric home of an aboriginal family group.

The little party, realizing the value of their discovery, decided to cover up the evidence of their find and return later to properly excavate the ruin, under the supervision of trained experts. It wasn't until 1939 that a return trip was able to be arranged and this was done under the sponsorship of the newly created Amerind Foundation. On this occasion, Dr. Emil W. Haury, a noted archaeolo-gist, scholar and teacher, along with two of his students from the University of Arizona, the Amerind staff, a cook and a Navajo interpreter comprised the exploring party. A federal government permit had been obtained to carry on the excavation work. Some rare archaeological finds were unearthed which today are housed in the State Museum at Tucson and the Amerind Museum at Dra-goon. "Gwendolyn" is the Amerind's most notable me-mento of this scientific expedition. She is a mummy, one of three that were found, and her remains, wrapped in a remarkably well-preserved cotton blanket and feather robe, lie in a glass case in the archaeological wing of the museum.

Since that expedition, the Amerind Foundation has supported and engaged in a number of other projects which have been under the direction of the foundation's resident archaeologist. Each digging has been followed up with the publication of the findings. Mr. Carr Tuthill was the resident archaeologist for six years.

At the present time Charles C. DiPeso is in charge. Dr. DiPeso is a graduate of Beloit College, in Wisconsin, and of the American Institute of Foreign Trade, near Phoenix. In 1951 he obtained his master's degree from the University of Arizona. His thesis covered the work he and Mr. Fulton had done on an old Indian site in Cochise County known as Babocomari Village. The interesting and historical information in DiPeso's thesis was published in book form by the Amerind Foundation.

Subsequently he received his doctorate as a result of an extensive "dig" at Quibiri, a prehistoric Indian site two miles north of Fairbank, Arizona, on the San Pedro river. Quibiri figures prominently in the early "Spanish contact" history of eastern Arizona and the Amerind Foundation museum now has a number of interesting and significant Quibiri artifacts. One of the most unusual items is a pair of spectacles which probably belonged to one of the early mission fathers. These glasses are inscribed "Nuremburg" and on one side still have an age-opaqued optical lens. A number of other things were unearthed, including pieces of European chinaware, bronze and copper shoe buckles, military uniform adornments and jewelry. This fascinating display occupies a glass cabinet in the museum. Collectively, these items, and the many Indian artifacts obtained, provide the clues and the evidence from which Dr. DiPeso has been able to fill in a historical gap between the prehistoric and historic occupation of the Quibiri site.

It might be of interest to look briefly at how such a "dig" is organized and operated.

By means of aerial photos (DiPeso was a P-38 pilot in World War II); by research done by other scholars in the past; by actual examination of the suspected site ruins; by reports of casual finds by local people; and by historical research in the voluminous files of various government and church archives in Mexico and California where ancient records are stored-by all these means the Amerind Foundation determined where actual digging was to begin.

The necessary leases and permits are obtained before the work starts. Promiscuous digging for relics is unlawful because much valuable material is lost forever by people who do not realize the significance of what they have found. To the experts these things are valuable, even the position in which they are found having importance. So careful are the archaeologists in this work and so meticulous the records they keep, that it would be possible to replace every artifact-every sherd, every bone, every bead-in exactly the same position from which it was unearthed. In the case of the Quibiri site this would have included a church, homes and numerous other buildings of a frontier presidio.

At Quibiri the excavating took over a year, with four “diggers” working along with Dr. DiPeso. One of the Spanish-American workmen, a youngster from Benson, became so interested in the work that before the summer was over he was giving lectures to his contemporaries in a social church group. Digging for relics is an almost fatal disease.

After publication of the Quibiri finds, work started on the San Cayetano del Tumacacori project, fourteen miles north of Nogales, near the stately roadside ruins of the old Franciscan mission, Tumacacori, which is now a National Monument. The San Cayetano site covered eighteen acres, and from it a host of material was recovered, much of it on display in the museum at Dragoon. A handsome 589-page book resulted from the San Cayetano project and among other things, it contains a detailed history of Pimería Alta, its people and the way they lived, worked and dressed. In lively and enjoyable style, author DiPeso covers the Spanish era as well. Even the sections necessarily devoted to "find" statistics are well edited, with many photographs. The bibliography is of impressive length.

Tentatively, the Amerind Foundation has lined up, as its next project, the excavation of the tremendous ruins at Aguas Calientes, in Mexico. Negotiations are underway with the Mexican government. Aguas Calientes has never been professionally excavated, though for years local "Pot-hunters" have unearthed much material, some of which has found its way into American museums and other collections. Aguas Calientes will be a three or four year project in conjunction with the Instituto de Antropología y Histor of Mexico. Dr. DiPeso will work as a "cooperative guest" with Dr. Ignacio Bernal, a widely known Mexican anthropologist.

Mexico has strict laws regarding the export of antiquities and art work, due to sad experiences in the past with foreign, free-booting expeditions. As planned now, all the Aguas Calientes material will be brought to the Amerind Museum for evaluation, study and repair; hence the need for the negotiations. After the project is complete and the reports all written up, the excavated material will revert to National Museum of Mexico City. Both Dr. DiPeso and Dr. Bernal look forward with eager anticipation to this project as there are indications at Aguas Calientes of some notable prehispanic material of the highly cultured Mexican Indians.

In addition to the wealth of material the Amerind Museum has collected as a result of its own excavations (seven, so far), it has a number of select items and collections of related interest which were acquired by purchase or by contribution. These items cover a wide range of subject matter as it is one of the Amerind Foundation's policies to provide as much material as possible for students and scholars in pursuit of their work on the history of the southwest.

One such outstanding acquisition for students of Apache lore is the White Mountain Apache Basket collection. These baskets are all of refined craftsmanship and design, well illustrating the Indian race's feel for vigorous artistic expression. The baskets are pleasingly arranged in a room that connects two wings of the museum.

Another display that visitors always find of much interest is the collection of bultos (hand-carved religious statues) that are effectively tableaued in the niched frame of an altar-shaped window in the west wing. They were carved by the inhabitants of the valley of the Rio Grande river in New Mexico, one and two centuries ago, under the guidance of the Roman Catholic priests who trekked up from Mexico after the conquest of the Aztec empire by the Spanish conquistadores. The officials of Spain's colonial acquisitions realized that all of the country in what is now the Southwest United States and northern Mexico had great strategic value as an outpost of their gold and silver empire to the south. So they encouraged the various religious orders to enter these far-off lands, build missions and Christianize the natives.

The Spaniards, the soldiers, the settlers and the clergy, were driven from the upper Rio Grande valley in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, but within a decade they were back in force. The routes up from Mexico City to the various northern settlements were so long and difficult to traverse that what few wagons, oxcarts and burro trains were sent up, hauled only the necessities. There wasn't too much room for religious items in the number necessary where each New Mexican household had a patron saint. So the Franciscan Fathers began making their own bultos, but the demand soon outgrew their capabilities. In time the job of carving their own religious statues passed on to the local parishioners, at which craft they proved to be singularly adept. The development of an almost stylized form of serene, simple grace was achieved. The bultos that have been recovered and are in private collections, of which the Amerind's is considered a fine one, suggest that had this primitive artistic development been allowed to progress, a native art form of great beauty and classic proportions might have resulted. Unfortunately, in 1854, Archbishop Lamy of Santa Fe ordered these simple expressions of benevolence and religious devotion, which he considered grotesque, to be replaced with the familiar plaster artwork.

Today these antique bultos are much sought after items. Amerind's collection has been gathered over a number of years.

The Amerind Museum also has a notable display of Inca pottery pieces. Some of them are intricately designed and all of them are superbly finished, the glaze in some cases being the equal, if not surpassing, that of the best ceramics being produced today.

Space does not permit further elaboration of the Amerind's other collections, all of which are tastefully displayed in bronze or hardwood cabinets. But a brief A mention of the library being built up should interest all biblophiles. They have a vast selection on the history, anthropology and archaeology of the Southwest and Mexico which includes a "working copy" of Francisco Clavijero's History of Mexico, a choice item, several of the classic works on Spanish Mexico, many old issues of the U. S. Bureau of Ethnology's reports, the journals of the various military mapping and topographical expe-ditions, and many others. Appointments by mail or telephone can be made to go through the Amerind Museum, though it is closed, during the summer months. Students and scholars are encouraged to use the facilities and it is the hope and ambition of both Mr. Fulton and Dr. DiPeso to have the Amerind's headquarters become an outstanding cultural center of the Southwest, thus fulfilling the purposes as stated in the articles of incorporation which read, in part, "to promote, finance and foster scientific, educational and archaeological study, pursuits, expeditions, excava-tions, collections, exhibitions and publications with par-ticular reference to the anthropology of the aboriginal people."

DESERT IN BLOOM

There is a rule for desert flowers, Their dry roots know it well: The time and place for desert showers No prophet can foretell; But in each patient root and seed A dormant magic lies, Eager to render instant heed To orders from the skies; Ready, no matter how long the wait, For swift and sudden duty, Helping the random rain create The desert's hour of beauty.

SATURDAY NIGHT IN A GHOST TOWN

Looking for excitement, frolic or fight, Wind-tipsy tumbleweeds wander all night On broken boardwalks with brush growing through And moon-bare streets where there's nothing to do, Bumping into buildings kneeling in sage, Deserted old buildings shaky with age, And running, head-on, not caring at all, Against weary fences, ready to fall, Until, tuckered out, and filled with remorse With dawn's gray coming, they steer a slant course Out of town towards a church whose sagging door Opens on neither a roof nor a floor.

PAINTER

In a distant city they exhibited his pictures, Called them good art, said he was giving Immortality to the town and the people Whose houses he painted to make a living.

CHANGELING

March is a hoyden, Boisterous, rude, With gusty anger And changing mood; For some days she softens Gives loving care To her wintry face And her wind-blown hair.

ROCKY ROAD

We lived one time on a wildwood hill, And the road went winding down By rocky twist and turn until It finally found a town, Where level streets run straight and true, Their elbows cornered square, With never a canyon's curlicue To thwart their thoroughfare. Though pleasant indeed are peopled streets, They cannot share the thrill Of slowing down for deer one meets, Winding a wooded hill!

ADOBE LIBRARY:

I have been a reader of your magazine for many years, and look forward to each new issue with a great deal of pleasure. There is a point of interest, however, on the Mission at Tumacacori, described in your September issue, which I would like to mention. The bricks in this Mission constitute a sort of "Adobe Library," for they contain the earliest record of the culture of barley and wheat in the Southwestern United States. This information was gathered by the late Professor G. W. Hendry of the University of California. And in this connection I would like to cite an article by him which appeared in Agricultural History Volume 5, No. 3, July, 1931, entitled, "The Adobe Brick as a Historical Source." I would like to make a second point and I must apologize for its dissenting nature. On page 23 of the October issue there is a field view labeled wheat. A close inspection of the foreground shows that all the heads are barley. This identification is concurred in my associates here working with barley and wheat. It is a small point, but I have a feeling that even an editor might be interested in a friendly chide now and then.

G. A. Wiebe, Head U. S. Dept. of Agriculture Agriculture Research Service Beltsville, Maryland

GOOD WORD ABROAD:

You may remember that last July you mailed me a package of a dozen assorted copies of the ARIZONA HIGHWAYS for spreading the good word about the United States and especially about Arizona during my visit to Russia to attend a congress of the International Astronomical Union. A somewhat belated return from Europe and consequent accumulation of work have delayed this note of thanks for your generous courtesy. You will be interested to know that the magazines were received with great interest and genuine gratitude. As many recent As writers have reported, the Russians have an immense interest in everything American, and are especially eager for sources of information which are free from political propaganda. Sometimes I could scarcely get across the hotel lobby without being asked for one of the copies of the ARIZONA HIGHWAYS which I was carrying. Four copies went to one of our interpreters who is a teacher in the sixth grade level of English (final year of high school) and who was very glad to have the copies to use in her classes. I am sure that they will be avidly read for a long time to come.

Edwin F. Carpenter Professor of Astronomy University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona

CACTUS:

Joseph Stacey is to be congratulated for his fine article on "Cactus" which appeared in your January issue. A cactus plant is one of Nature's great triumphs.

E. M. Salton Cleveland, Ohio

CHRISTMAS ISSUE:

Your Christmas issue came up to expectations. Congratulations for selection of pictures but especially for the reproductions. Being in the printing business myself I always watch for and admire superb color work. Your Christmas issue is a milestone in graphic arts.

E. M. Willets Spokane, Washington

OPPOSITE PAGE

"TROUT WATER-EAST VERDE" BY RALPH FISHER, JR. Universal Uniflex I camera; 120 Ektachrome; f.16 at 1/50th sec.; Universal anastigmat 75mm f.5.6 lens; midMay; clear day, mid-morning. Scene taken on the upper East Verde River near Flowing Springs, about six miles northwest of Payson, Arizona. Turn right at sign that reads Flowing Springs just before you reach the steel bridge over the East Verde at Verde Park. This trout stream is mostly stocked from the Tonto Fish Hatchery. Trees along the stream are mainly scrub junipers, cedars with many century plants growing on the rocky hillsides.

BACK COVER

"TROLLING-LAKE MEAD" BY CLIFF SEGERBLOM. Rolleiflex camera; Ektachrome; f.8 at 1/50th sec.; Schneider Xenar 3.5 lens; spring; sunlight, open shade; ASA rating 32. Photograph taken at Wishing Well Cove on Lake Mead on the Arizona side of Boulder Canyon about fifteen miles north (or upstream) from Hoover Dam. Lake Mead has become one of the most popular fishing centers in the West. Hundreds of miles of shoreline offer countless coves where fishing is good and the scenery unsurpassed.

Already a member? Login ».