Nature Photography

NATURE PHOTOGRA

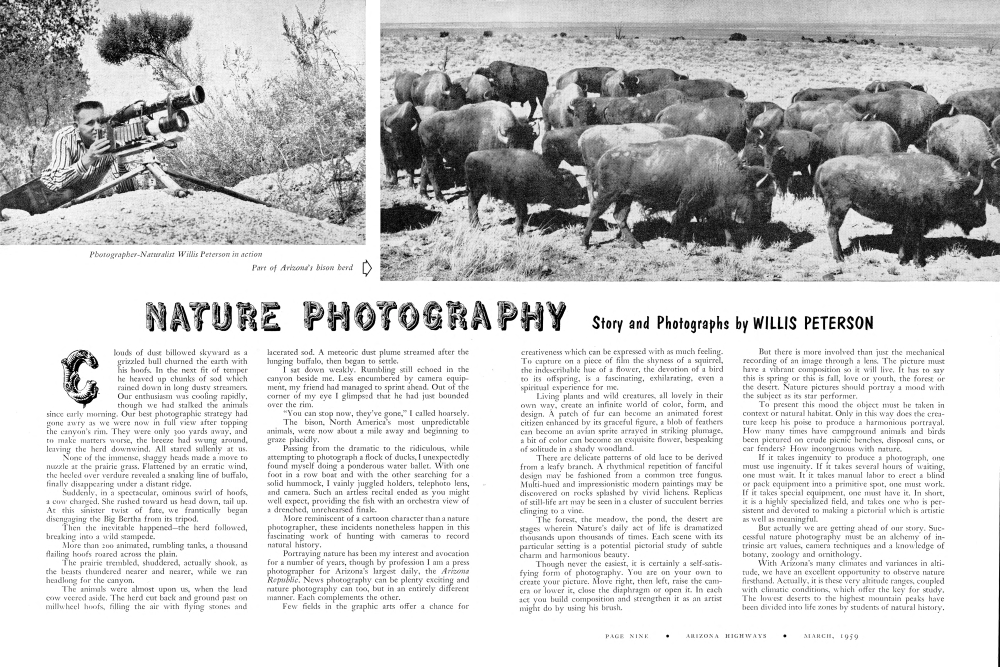

Clouds of dust billowed skyward as a grizzled bull churned the earth with his hoofs. In the next fit of temper he heaved up chunks of sod which rained down in long dusty streamers. Our enthusiasm was cooling rapidly, though we had stalked the animals since early morning. Our best photographic strategy had gone awry as we were now in full view after topping the canyon's rim. They were only 300 yards away, and to make matters worse, the breeze had swung around, leaving the herd downwind. All stared sullenly at us. None of the immense, shaggy heads made a move to nuzzle at the prairie grass. Flattened by an erratic wind, the heeled over verdure revealed a snaking line of buffalo, finally disappearing under a distant ridge. Suddenly, in a spectacular, ominous swirl of hoofs, a cow charged. She rushed toward us head down, tail up. At this sinister twist of fate, we frantically began disengaging the Big Bertha from its tripod. Then the inevitable happened the herd followed, breaking into a wild stampede. More than 200 animated, rumbling tanks, a thousand flailing hoofs roared across the plain. The prairie trembled, shuddered, actually shook, as the beasts thundered nearer and nearer, while we ran headlong for the canyon. The animals were almost upon us, when the lead cow veered aside. The herd cut back and ground past on millwheel hoofs, filling the air with flying stones and lacerated sod. A meteoric dust plume streamed after the lunging buffalo, then began to settle. I sat down weakly. Rumbling still echoed in the canyon beside me. Less encumbered by camera equipment, my friend had managed to sprint ahead. Out of the corner of my eye I glimpsed that he had just bounded over the rim. "You can stop now, they've gone," I called hoarsely. The bison, North America's most unpredictable animals, were now about a mile away and beginning to graze placidly. Passing from the dramatic to the ridiculous, while attempting to photograph a flock of ducks, I unexpectedly found myself doing a ponderous water ballet. With one foot in a row boat and with the other searching for a solid hummock, I vainly juggled holders, telephoto lens, and camera. Such an artless recital ended as you might well expect, providing the fish with an orchestra view of a drenched, unrehearsed finale. More reminiscent of a cartoon character than a nature photographer, these incidents nonetheless happen in this fascinating work of hunting with cameras to record natural history. Portraying nature has been my interest and avocation for a number of years, though by profession I am a press photographer for Arizona's largest daily, the Arizona Republic. News photography can be plenty exciting and nature photography can too, but in an entirely different manner. Each complements the other. Few fields in the graphic arts offer a chance for

PHY Story and Photographs by WILLIS PETERSON

creativeness which can be expressed with as much feeling. To capture on a piece of film the shyness of a squirrel, the indescribable hue of a flower, the devotion of a bird to its offspring, is a fascinating, exhilarating, even a spiritual experience for me.

Living plants and wild creatures, all lovely in their own way, create an infinite world of color, form, and design. A patch of fur can become an animated forest citizen enhanced by its graceful figure, a blob of feathers can become an avian sprite arrayed in striking plumage, a bit of color can become an exquisite flower, bespeaking of solitude in a shady woodland.

There are delicate patterns of old lace to be derived from a leafy branch. A rhythmical repetition of fanciful design may be fashioned from a common tree fungus. Multi-hued and impressionistic modern paintings may be discovered on rocks splashed by vivid lichens. Replicas of still-life art may be seen in a cluster of succulent berries clinging to a vine.

The forest, the meadow, the pond, the desert are stages wherein Nature's daily act of life is dramatized thousands upon thousands of times. Each scene with its particular setting is a potential pictorial study of subtle charm and harmonious beauty.

Though never the easiest, it is certainly a self-satisfying form of photography. You are on your own to create your picture. Move right, then left, raise the camera or lower it, close the diaphragm or open it. In each act you build composition and strengthen it as an artist might do by using his brush.

But there is more involved than just the mechanical recording of an image through a lens. The picture must have a vibrant composition so it will live. It has to say this is spring or this is fall, love or youth, the forest or the desert. Nature pictures should portray a mood with the subject as its star performer.

To present this mood the object must be taken in context or natural habitat. Only in this way does the creature keep his poise to produce a harmonious portrayal. How many times have campground animals and birds been pictured on crude picnic benches, disposal cans, or car fenders? How incongruous with nature.

If it takes ingenuity to produce a photograph, one must use ingenuity. If it takes several hours of waiting, one must wait. It it takes manual labor to erect a blind or pack equipment into a primitive spot, one must work. If it takes special equipment, one must have it. In short, it is a highly specialized field, and takes one who is persistent and devoted to making a pictorial which is artistic as well as meaningful.

But actually we are getting ahead of our story. Successful nature photography must be an alchemy of intrinsic art values, camera techniques and a knowledge of botany, zoology and ornithology.

With Arizona's many climates and variances in altitude, we have an excellent opportunity to observe nature firsthand. Actually, it is these very altitude ranges, coupled with climatic conditions, which offer the key for study. The lowest deserts to the highest mountain peaks have been divided into life zones by students of natural history.

In each zone there are certain plants which are usually indicative of a particular altitude. The interdependence of temperature, rainfall and such plants-many of which offer generous forage-with animals and birds living in the same altitude range, broadly constitutes a life zone. Consequently, we find at given altitudes much the same flora and fauna throughout the State.

Arizona is one of the few states where five distinct life zones exist. From the hot deserts they march upwards, starting with the Lower Sonoran. The Upper Sonoran, the Transition, the Canadian, and the Hudsonian follow. Even a hint of the sixth, the highest, the Alpine Zone, embraces the top of the San Francisco Peaks, near Flagstaff.

A survey of these zones and their plant and animal associations is of the utmost importance to one endeavoring to photograph nature. By keeping these ranges in mind in step-ladder form, it becomes much easier to determine where such associations may be sought.

For example, in a whirlwind tour of Arizona we find on Mingus Mountain, in the Canadian Zone, an excellent area for observing and photographing the Abert squirrel. Rocky Mountain mule deer abound here too, but are somewhat wary.

Anderson Mesa, a little lower in altitude, and in the Transition Zone, offers an excellent habitat for pronghorn antelope. To the east, under the Anderson Mesa rim, in a special range controlled by the Arizona Game and Fish Commission, buffalo continue to find the open prairie as it used to be.

The North Kaibab Plateau, in the Hudsonian and Canadian Zone, contains the largest herd of Rocky Mountain mule deer in Arizona. Many are quite tame and can be readily photographed from the highway. Flocks of Merriam turkey also seek the solitude of this forest to rear their young.

Another fascinating animal is the Kaibab squirrel, found nowhere else in the world. Oak thickets harbor the dusky grouse, a very elusive game bird. A number of species of wild berries can be discovered as well as wildflowers.

The Kaibab supports some of the largest aspen groves in Arizona. The gleaming white trunks remind one of stately Grecian columns. In the fall, their golden leaves make handsome pictorials.

South from Flagstaff lies the Mogollon Rim, most of which lies in the Canadian Zone. The Rim is a huge escarpment leading across Central Arizona into New Mexico. Aside from scenic grandeur, many photographic subjects are available, particularly fungi. Fallen and decaying forest vegetation along with moist conditions make this one of the best areas for mushroom hunting. Ranging from red to green, these fungus growths develop into intricate shapes, creating fascinating subject material. Clinging to rocks and tree trunks are the multi-hued lichens. Though profuse in almost every climatic zone, they are more prevalent in these higher altitudes.

Traveling east from the Mogollon Rim, we enter the White Mountains, the upper portions of which lie in the Hudsonian Zone. Here, during the month of August. Arizona's showiest array of mountain wildflowers are on display. Particularly colorful are the scarlet penstemons and Indian pinks. Huge areas of lavender asters mingle with fields of white Fleabane daisies. Wet meadows tucked away in the spruce forests yield yellow Alpine sunflowers. At Sheep Crossing, on the Little Colorado, clumps of yellow and blue columbines beckon with their photogenic petals.

Southern Arizona presents a somewhat different ecological aspect. In this portion of the State, large unrelated mountain masses are isolated from each other by low, hot deserts. The Chiricahua, Huachuca, and Santa Rita Mountains are good examples. Because of this isolation, and the influence of adjacent semi-tropical Mexico, there are a number of plants and creatures which live in these mountains, but are not distributed farther north. The coati, ocelot and jaguar are strictly tropical animals, yet they occur within these Southern Arizona mountains. The Coppery-tailed Trogon, and a number of other birds, are also restricted to these ranges and Mexico.

Surrounding Phoenix, the deserts of the Lower and Upper Sonoran Zones, extending into the Transition Zone, present their own peculiar forms of life. Cacti predominate with a multitude of species challenging the photographer to portray their grotesque branches and delicate blossoms.

Among the desert's fascinating birds is the Gambel's quail, a bird any camera fan would be happy to shoot. The cactus wren is another unique bird. The largest of the wrens, it prefers to build its nest in low cactus branches. The jaunty Arizona cardinal, dweller of arid lowlands, is a handsome resident, decked out in vermilion headdress and black mask and bib.

In these hot regions, the night hours are prone to be more popular for much of the wildlife. Consequently, most desert animals must be observed and photographed during their nocturnal sojourns. The Arizona gray fox, skunk, badger, ringtailed cat, and kit fox favor the cover of darkness. All the species of kangaroo rats, pack rats, in fact, most of the rodents, also seek the cooler portions of the night to carry on their activities.

Such a gamut of wildlife, from these tiny, nocturnal, desert creatures to pronghorn antelope, deer, and bison, mammoth in comparison, requires a considerable amount of special photographic gear, much of which revolves about adaptations of different focal length lenses.

In this respect, I use four cameras, three of which are 34x44 Speed Graphics. One Graphic houses a 127mm, f-4.7 Ektar lens. This short focal length lens is handy for flowers and other closeup still-life. The other camera is equipped with a 135mm, f-4.7 Ektar lens with a shutter synchronized for electronic flash. This "Speed" is operated for birds and animals where fast shutter action is needed. When impossible to set the camera in a close position, I substitute an f-5.5, 240mm Tele Xenar, also synchronized for electronic flash.

For antelope, deer, bison, other large animals and birds, which have to be stalked or shot from a distance, I change to a 20 inch f-5.6 Bausch and Lomb telephoto. This lens is also mounted on a 314x414 Speed Graphic. As can be imagined, standardization of these three cameras to the same film size is imperative. Different size holders for each camera would confuse matters to the extent that one would give up nature photography and chuck everything into the nearest canyon.

Water holes make excellent locations

The fourth camera is a 35mm Exakta, equipped with an f-5 500mm Astro lens. This I find perfect for bird slides. Of course, different focal length lenses can be interchanged at a moment's notice for any occasion.

Small wildlife present a considerable problem to the photographer since they are constantly moving about, and most of them prefer shade to bright sun. By attracting animals with food, it is far easier to bring them to the camera where sunlight is available or where supplementary light can be utilized.

All wildlife have definite foraging habits. If a squirrel should pass by your camp in his quest for nuts and other food, there are nine chances out of ten that he will pass by at nearly the same time the following day, by the same trees, by the same rocks. Such regular habits are also displayed by most wildlife when leaving and returning to the nest or burrow.

After observing these behavior patterns it is a fairly simple matter to "cut the trail" with tasty and aromatic bait. This I do by laying a string of crumbs at right angles to the apparent pathway, with a large pile of crumbs heaped against a suitable photographic background.

When the creature crosses this line of bait he begins to investigate. In a few moments he discovers the larger cache, and thus stays on to partake of this windfall. Though unknown to himself, he cooperates with me to the fullest extent.

This procedure works equally well for nocturnal animals as for those active in the daytime. Various species, of course, require different types of bait. Decoying wildlife by placing bait for them is intriguing in itself. In my own experience, I have had to use all the wiles of a fur trapper to induce reticent animals to my camera, paying out as tribute graham crackers for squirrels, aspen bark for beaver, salt for porcupines, canned dog food for skunks, cantaloupe rinds for coati and chicken necks for badgers and foxes.

Enticing birds to the camera with food is somewhat more difficult. Some exist on a limited type of diet, particularly the insectivorous birds. The best method to attract them is by feeding feeding tables where an assortment of tidbits may be offered. With convenient photogenic perches for the birds to alight on near the table, it is possible to make photographs with natural backgrounds.

A more rewarding way, however, is locating their nest of young and waiting until the parent birds arrive to feed their little ones. Instinct or mother love, or call it what you will, is strong enough to make the bird reconsider any hazard. Even with the camera inches away from the nest, few birds will willingly abandon their young.

Practically all fauna must drink at some time, and thus waterholes become extremely effective means to obtain pictures of both animals and birds. The shooting site should encompass only a small area. The camera angle, then, need not be changed to cover one side or the other, minimizing the chance of losing a picture.

This type of photography indicates the camera must be prefocused, preferably through the groundglass, the only absolutely sure method to show what will be contained in the picture. The approximate length of the subject should be assumed and the camera focused so this assumed size is centered proportionately.

Animals and birds quickly sense that the camera is an inanimate object and soon regard it as part of their environment. I've often had fledgling birds alight on the camera as they leave their nest, to say nothing of a male quail that used the top of my camera for a look-out while his mate drank at a waterhole.

Many rodents, including wary squirrels, have taken portions of choice bait which I have meticulously placed for them against a carefully worked out background, only to clamber on top of the camera's rangefinder and contentedly munch my offerings. Such incidents prove amusing, though at the time they they may leave a disgruntled photographer.

The critical problem, then, is setting off the shutter at precisely the right moment, for this timing can either make or break the picture. It is difficult at best, since it must be released when the animal assumes the right posiCaution without the photographer being there to frighten the subject away.

The flash bulb, though convenient and safe, is not quite adequate, chiefly because of its inability to stop fast action. One must remember that physical reaction time in birds and animals is much quicker than ours. Even if a shutter is set at 1/50th or 1/100th of a second there still may be movement which will cause the image to blur.

NOTES FOR PHOTOGRAPHERS OPPOSITE PAGE

ABERT SQUIRREL Sciurus aberti Inhabiting the conifer forests of Arizona, the Abert squirrel can be heard barking, but is very difficult to find and much more difficult to photograph. Here he sits on the floor of the forest and drinks a refreshing draught of rainwater.

FOLLOWING PAGES

RINGTAIL CAT-Bassariscus astutus-Found in all of the Southwestern states, the ringtail cats are so shy that not many people know them. They make their home in cliffs along desert canyons. Their favorite food consists of rodents and large insects. Much of their time is spent sleeping in the semi-darkness of their den.

AMERICAN BISON-Bison bison-The bison once roamed all of the North American continent but were hunted to such an extent that they almost became extinct. Since then the herds have been protected and kept in special ranges. Bulls will often weigh more than a ton and stand 5 to 6 feet tall. Both male and female have horns.

MULE DEER-Odocoileus hemionus These deer are called mule because of their large ears which resemble a mule's ears. During the summer months these deer browse on high, rocky ridges and when fall comes they move down to the open forests. The common running gait of the mule deer is to spring from the ground with all four feet at the same time.

PRONGHORN Antilocapra americana Pronghorns are nervous and shy creatures but exceedingly curious. When any new thing is spotted on their range they will invariably come to investigate. If a pronghorn is frightened the two white clumps of hair on his rump stand up like flashing rosettes, then he springs away. This is signal to other antelope that danger is near. Their fawns, usually twins, are born during May and June.

TEXAS HORNED LIZARD-Prynosoma cornotum Horned lizards are found only in the western part of the United States and Mexico. They feed on insects, especially red ants. These unusual lizards may squirt a thin stream of blood from the corners of their eyes when frightened. Some puff up when angered; others flatten themselves.

SPINY SWIFT-Sceloporus jarrori Swifts make up a large part of the common lizards. They are often seen on trees, on boulders, and among rock ledges and true to their name they are hard to catch. Some 30 species and subspecies live in the U.S. The largest have bodies about 5 inches long with tails slightly longer.

GILA MONSTER LIZARD-Heloderma suspectum The Gila Monster is the only poisonous lizard in the United States. They will grow to two feet in length feeding on eggs, small rodents and other lizards. Usually slow and clumsy, this lizard can twist his neck and move his head from side to side in lightning-like movements when he becomes agitated.

LEOPARD LIZARD-Crotaphytus wislezeni The leopard lizard has a long slender body and is more or less spotted. It feeds on insects and other lizards. The female lays from two to four eggs which hatch in a month. Like some of the giant prehistoric lizards, the leopard lizard is also able to run erect on its hind legs.

GRAY FOX-Urocyon cinereoargenteus This fox is found in the western and southern part of the United States. Its favorite habitat is in rough country and canyons where it can make its den in rocks and hide in brush. It is rather small, weighing from 10 to 18 pounds and is about 40 inches long, including his 18 inch tail. Usually three or four young are born in the early spring.

SWEETHEART MOTH-Catocala amatrix A night-flying moth, the Sweetheart resembles a large gray fly when resting. As it flies it shows its brightly colored hind wings, and hence, falls into a group of moths known as the underwings. It feeds on sap and nectar.

DARITIS MOTH-Daritis thetis So rare is this insect that only a few have been discovered. This beautiful moth has so far only been collected in Southern Arizona, but possibly its range extends into Mexico.

HOARY BAT Lasiurus cinereus This bat is a solitary type, preferring to roost alone. Unlike many bats it prefers trees to hang in rather than caves or crevices. It inhabits the greater part of the United States.

PORCUPINE Erethizon dorsatum He is the only mammal in the U.S. which bears quills. Total length is about 30 inches with a nine inch tail. As a youngster, he feeds on tender grass. When mature, his diet consists of conifer tree bark and leaves. Few animals will tangle with the porcupine for at the slightest touch on the part of the attacker he will have a face full of quills.

NOTES FOR PHOTOGRAPHERS Continued

RED SPOTTED PURPLE Basilarchia astyanax This butterfly is so named for its red spots on the under side along the wing borders and at the base of the hind wings. The larvae feed on wild cherry, willow, and other trees, preferring shaded woods.

TIGER SWALLOWTAIL BUTTERFLY-Papilio turnus One of the larger butterflies, it has a wingspread of 3½ inches. This beautiful butterfly has been nominated as our national butterfly. More than 20 species of the swallowtails occur in the United States, and all are predominantly black or yellow.

COATI-Nasua narica A cousin of the raccoon, the coati is a rusty brown animal with a long tail and a pig-like snout. His nose is used for rooting among leaves and rocks in search of insects, grubs, and tubers. Coatis are gregarious, often roaming the forests with as many as 200 in their band. Though a tropical species, they are found in the Chiricahua and Huachuca Mountains of Arizona.

DESERT TORTOISE Gopherus agassizii An interesting denizen of the Southwest is the land tortoise. He is also protected by game officials. He may be likened to a knight of old in that he is fully equipped with armor and carries his own lance. He is completely vegetarian.

TREE FUNGUS Ganoderma lobatum This fungus frequents the hardwoods, particularly oak. As the fruiting bodies become older they also become browner and less colorful. New fruiting bodies have just formed near the top.

FLY AMANITA MUSHROOM Amanita muscaria Known to many as the "death cup" this plant is deadly poisonous. The plant erupts from an egg-shaped tissue leaving a cup like membrane about the stem's base, hence its name. They can be found growing in all parts of the country all during the summer and until the first frost.

RUSSULA MUSHROOM-Russula heterophylla The various Russulas are the brightest mushrooms found in the forest. Their colors range from the brightest reds to green, purple, violet, and yellow. Some are edible and some are not. Because of the great variances within the species they are quite difficult to identify.

LICHENS Caloplaca A lichen is a partnership, consisting of two kinds of plants. Each specimen is a fungus with a large number of alga cells growing inside it. The alga cells make food that the fungus also lives on. The fungus absorbs water and mineral matter and apparently gives the alga some protection.

LICHENS Parmelia Lichens are the toughest of all plants in resisting the elements. They grow in places where nothing else could live, on antarctic mountains where the temperature rarely climbs above freezing and on desert rocks at temperatures of 170 degrees F. The "reindeer moss" of northern Canada is a lichen.

GOLDEN DAISY Aplopappus gracilis The golden daisy is often found making large displays with its vivid color on dry plains, mesas and rocky slopes in Southern Arizona. Its tiny, yellow flowers bloom from early spring until late fall.

WATER HYACINTH Eichhornia crassipes A native of South America, the water hyacinth has become naturalized in the southern part of the United States. The violet flowers grow on a spike about 8 to 10 inches above the water. They have floating leaves and spongy stalks filled with air chambers.

SANDVERBENA Abronia villosa The pink to lavender blooms of this low-growing herb are found in sandy locations throughout all of the Southwest deserts. They bloom from March to April in the desert and during the early summer in higher elevations.

OREGON GRAPE Berberis repens A very low-growing shrub with bluish grape-like fruit. It is found on dry, rocky slopes, and is especially abundant along the Grand Canyon rims. Deer are quite fond of its leaves and berries. Because of its spiny-edged leaves it is often mistaken for holly.

MERRIAM TURKEY Meleagris gallopavo merriamiThis turkey differs from the eastern wild turkey in having whitish tips on the tail-feathers instead of chestnut. They live in small flocks the year round and can often be seen in the open meadows of the forests as they feed on grass, seeds, and insects. At night they roost in the tops of trees.

ARIZONA CARDINAL - Richmondena cardinalis superba - The cardinal is an exceedingly colorful bird, mostly red with a black bib under his bill. With their cheerful and melodious song they are welcome guests at any feeding table. The male is a devoted parent and tirelessly searches for insects to keep his family well fed.

WESTERN BLUEBIRD Sialia mexicana occidentalis Here, a male bluebird and a juvenile bird drink at a waterhole. The bluebird is a little larger than a sparrow, with head, wings, and tail blue. Breast and back are rusty-red. They breed in the higher foothills and pine belts throughout the West.

In overcoming this drawback, the advent of the electronic flash, in my opinion, has been one of the greatest assets to the nature photographer. I cannot praise it highly enough, and the equipment is quite flexible if it is used in the right manner.

By balancing the electronic flash with daylight, it is possible to get a light or dark background depending upon the shutter setting, and still have the foreground frozen. This is not as difficult as it sounds.

For example, let us make a transparency of a bird's nest situated in the shade. A meter reading would require 1/50th of a second at f-2. But beyond, in the sun, the meter reading would be 1/50th of a second at f-11.

The procedure, then, is to set the lights at the required distance, which, by their intensity and short duration, will freeze everything at 1/1000th of a second in the deep shadow. Yet the shutter speed is set for the daylight filtering through the branches. Consequently, we have a well-balanced picture, needle-sharp in the foreground, but still leaving the background light. The other method is to make sure that all the background is within range of the flash, and is therefore exposed equally well as the subject. The distance from the subject to the lights governs the f stops.

I use two lights, standing almost opposite each other. One acts as a key light, which is placed higher, and the other acts as a fill-in, placed at a lower plane. This arrangement simulates more closely natural lighting. The fill-in softens the shadows, creating a roundness effect. Modeling is extremely important, and can rarely be achieved by the use of a single light.

Letting the animal take his own picture is an exciting facet of wildlife photography. This can be done easily enough by using a mouse trap which acts as a tripping switch. The technique is to tie a fine, though stout thread to a root or trunk with about an inch clearance from the ground. This thread passes over the bait and is attached to the trap trigger. When disturbed, the thread springs the trap. As the arm swings down, it brushes against a soldered wire lead, completing the circuit, and firing the flash.

But one never knows which way the subject may be facing, and hence some of the results may be somewhat discouraging. Obviously, one does not want to take a picture when the animal's eyes are closed, or if he has laid back his ears, or if he has turned his head away, or if he has backed toward the camera and only a portrait of his tail would result.

The most successful method to overcome these awkward positions is to set off the shutter visually from a blind, and diligently use a pair of field glasses to determine when the animal is in the precise plane of focus. Spotlights are needed at night. Though the beam may be exceptionally high-powered, animals do not seem to be frightened of a stationary light. Blinds are not hard to construct. If the animal is particularly cautious, it may be necessary to make the camera setup and build the hideout several days before actually making any photographs. The more simply made, the more practical. In fact, ordinary brush piles serve the purpose very well. Low bushes and clumps of weeds are just as effective. Strange as it may seem, cars make good blinds. For some reason, wildlife exhibit little fear of a man in an automobile.

It is best to wear dark clothing, which makes one much less conspicuous behind a camouflage. The cardinal point to keep in mind is not to make any quick move-ments the one thing that all wildlife associate with dan-ger. An indiscreet move may take days to rectify.

The lure of wildflower beauty is universal, inviting the photographer to show his skill in lighting, composi-tion, and camera techniques. But flower photography also presents its own set of problems.

The most important point to remember is to keep the background simple. This can be done in two ways, first, choose a background which is plain and uncluttered. Second, by selective focus. In the latter, an examination through the groundglass will reveal the best aperture. Large f stops leave the background less sharp than smaller diaphragm openings. Usually the bigger stops make better flower pictorials.

In some cases there may be too bold a delineation between shadow and light. Then, selective focus may not be able to soften the background enough. Portable back-ground of stiff (show card) pasteboard may have to be used. These large cards, 28x22 inches, can be had in several colors.

But being of solid colors, they do not enhance the subject with that subtle mottling of complimentary hues, which only natural backgrounds can offer.

Time of day dictates lighting conditions. Backlighting and sidelighting as a rule make far more interesting pictures than flatlighting.

Wind creates the greatest problem in photographing flowers. I have waited many hours for a lull, and that seems to be about all that can be done. Large cardboards are helpful to deflect the breeze provided it is not a steady wind.

Fungi, wild berries and lichens are quite easily photographed with the wind problem practically eliminated because of their more stable stems and growing conditions.

Here is where closeup techniques are at a premium. It is far better to shoot "tight" than take in a large area. If the exposure contains several centers of interest, which invariably happens when the camera includes too great a field, the original theme has lost its appeal.

In the same vein, insects must be photographed from close range lest their configuration be lost. A change from normal exposure must be made when using long bellows extension for extreme close-ups, complicating matters somewhat. But luckily, photographic stores carry handy exposure calculators which are designed for on the spot usage.

Many camera fans, I know, have fixed focus or cameras which have unchangeable lenses. In this case, the addition of a protar lens solves much of the problem in getting close-up images. They are available in many sizes.

Obviously it would be impossible to discuss all facets in the realm of nature photography. And actually, it wouldn't be a good idea.

Experimentation and discovery are the tribulations and fruits of any worthwhile project. Without them life would be indeed dull, and nature photography would merely be a push-button affair.

So, borrow the spirit of Columbus or Magellan, arm yourself with your favorite camera and discover the fleet-ness of the forest deer, the thrill of spying on a flock of wild turkeys, the lovely lavender haze of asters blooming in a meadow.

Keep your shutter cocked, your eye ready. There should be good hunting ahead.

TOOLS OF THE TRADE

Lenses, cameras, holders, electronic flash equipment, plus an array of small, but significant items, constitute the tools of the trade. Without becoming a gadgeteer, the specialized photographer finds a specific need for all his gear. Displayed here is the equipment used in making these nature studies.

Much wildlife must be shot by telephoto equipment to bring it close enough to make a recognizable image on the film. This lens (1), a 20" Bausch and Lomb telephoto, is coupled with a viewfinder-rangefinder of my own design. Time is an extremely important element in photographing animals. There are many occasions when it becomes impossible to focus through the ground-glass, close the diaphragm, wind the shutter and still shoot a pic-ture before the subject vanishes. With this arrangement I can focus and frame the image without extracting the holder. The principle acts in the same manner as a twin lens reflex. Viewing lens and telephoto lens are coupled. By turning a single focusing knob both lenses are focused in the same action. These lenses are mounted to a 34 x 4% Speed Graphic camera (2).

The lens which I am holding (3) is a 500mm f-5 Astro, also used for distant subjects, especially birds. It is adapted to a Kine Exakta (4), a 35mm single lens reflex camera. Item (5) is the main light of a portable Hershey Sun-Lite electronic flash. The extension unit (6) acts as a fill-in light for modeling effects. These Sun-Lites, I find, are superior to flash bulbs, chiefly because of their speed, about 1000th of a second. This eliminates movement and blurred images.

The elevator type tripod head (7) is ideal for telephoto work because the camera can be raised or lowered with a minimum of motion on the part of the photographer.

This Graphic (8) I operate mostly for animals and birds. It houses a (9) 135mm Ektar f-4.7 lens with shutter synchronized for electronic flash. The tripod (10) which this camera rests on is an Otto Senior, made of wood. It is practical in that it can be set up in water, mud or sand without damage.

The handiest of my carrying cases is a 50 caliber ammunition box (11). Sand proof and water proof, it can store eighteen holders plus light meter and filters. Bigger than the ammo box is a heavy wooden case (12) which holds all the 35mm equipment.

Item (13) is an important piece of equipment, the Sun-Lite AC adapter used for the electronic flash. Actually, it is a battery saving device employed when regular 110-volt house current is available. The Sun-Lite battery power pack (14) for the flash is quite portable and can be packed into any primitive area. Item (15) includes the two aluminum stands needed to hold the electronic flash heads.

In photographing animals from blinds, long extension cords are needed to operate the camera. This (16) is a 100' cord. Occasionally I employ flash bulbs for supplementary lighting. Again, the use of an extension (17) is imperative to obtain good model-ing. An extra flashgun (18) has the dual purpose of adding electrical power by special connectors for long shutter cords. It can also be used directly to trip the shutter.

Many times a longer focal length lens is needed when the camera cannot be set up at close range. In this case a 240mm Tele Zenar f-5.5 (19) usually fills the bill. There are, of course, times when a wide angle lens is needed. On such occasions I interchange a 90mm Wide Angulon f-6.8 (20).

Item (21) is another 100' extension cord. My light meter (22) is a Dejur Professional which I have used since 1948. This flashgun (23) can operate the shutter of either camera. A tape (24) is a necessity for measuring the distance from the lights to the subject to calculate exposure.

Film holders (25) are an integral part of any photographer's equipment. With the exception of the Exakta, all my cameras use the same size holders, 29 in all. This third 3% x 4% Speed Graphic (26) I use mostly for still life, flowers and forest subject matter. It houses a 127mm f-4.7 Ektar lens (27). Aside from the wide angle lens this is the shortest focal length used with the cameras.

A combination extension cord (28) of 15', 30', and 55' proves very practical. With these lengths, any desired shutter cord footage may be produced. By adding the other two 100' cords, up to 300' may be obtained.

Already a member? Login ».