Fort Bowie

OLD FORT

A hundred years ago-when the seeds of history and legend were being planted in Arizona for harvesting by the fictioneers of a softer civilization -the Southern Overland stagecoach offered a tempting travel bargain to any American afflicted with wanderlust. For the sum of $150 plus meals, John Butterfield's bullhide-sprung Concords would pick him up in Missouri and transport him 2,535 miles to San Francisco in 585 hours. What the ticket vendors neglected to mention, however, was a growing tendency on the part of Mr. Lo's Arizona cousins to disrupt advertised timetables across their tribal hunting grounds in present-day Cochise County. The stage traveler entering Arizona had no better than an even chance of not having his journey delayedor terminated-by welcoming committees in breechclouts and warpaint, ready to punch his through-ticket with musketball or arrowhead.

By far the most dangerous point on the southern transcontinental route was a six-mile stretch of the Mesilla-Tucson division, where the road lifted itself over a gap separating the Chiricahua and Dos Cabezas mountain ranges. Stage drivers called this leg "Hell's Gate" or "Suicide Run."

We know it today as Apache Pass.

As an incentive to keep the Concords rolling, Butterfield-and later on, Tom Jeffords-paid triple wages to those hardy jehus lucky enough to complete the Apache Pass run. Despite the pass' reputation as the West's bloodiest death trap, the stage company rarely lacked for reinsmen or fare-paying clientele. It took the Pony Express competition and the dislocation of Civil War to halt Butterfield's traffic across Apacheria.The Apache Pass road was already fenced by the grave boards of uncounted massacre victims in July, 1862, when a combined force of Chiricahua and Warm Spring Apaches, under Cochise and Mangas Coloradas, ambushed a column of Union infantry, cavalry and artillery seeking a spring east of the summit. These troops, numbering fourteen companies, would have been decimated had not

BOWIE GUARDIAN OF APACHE PASS

The Indians been panicked by the thunder of the paleface “shooting sticks on wheels”-field artillery howitzersand withdrew posthaste.

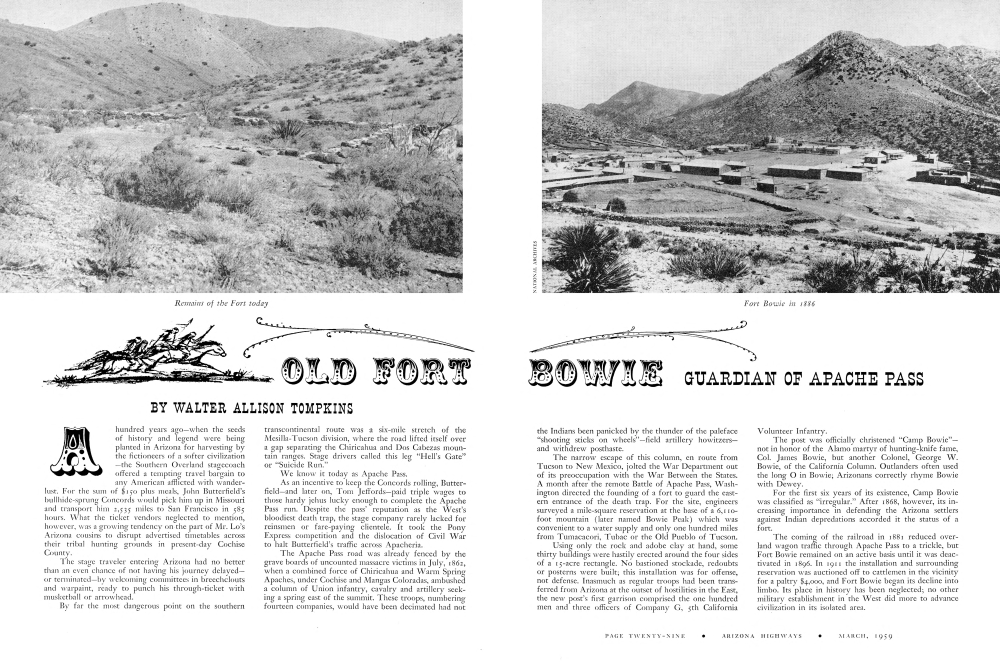

The narrow escape of this column, en route from Tucson to New Mexico, jolted the War Department out of its preoccupation with the War Between the States. A month after the remote Battle of Apache Pass, Washington directed the founding of a fort to guard the eastern entrance of the death trap. For the site, engineers surveyed a mile-square reservation at the base of a 6,110foot mountain (later named Bowie Peak) which was convenient to a water supply and only one hundred miles from Tumacacori, Tubac or the Old Pueblo of Tucson.

Using only the rock and adobe clay at hand, some thirty buildings were hastily erected around the four sides of a 15-acre rectangle. No bastioned stockade, redoubts or posterns were built; this installation was for offense, not defense. Inasmuch as regular troops had been transferred from Arizona at the outset of hostilities in the East, the new post's first garrison comprised the one hundred men and three officers of Company G, 5th California Volunteer Infantry.

The post was officially christened “Camp Bowie”not in honor of the Alamo martyr of hunting-knife fame, Col. James Bowie, but another Colonel, George W. Bowie, of the California Column. Outlanders often used the long O in Bowie; Arizonans correctly rhyme Bowie with Dewey. For the first six years of its existence, Camp Bowie was classified as “irregular.” After 1868, however, its increasing importance in defending the Arizona settlers against Indian depredations accorded it the status of a fort.

The coming of the railroad in 1881 reduced overland wagon traffic through Apache Pass to a trickle, but Fort Bowie remained on an active basis until it was deactivated in 1896. In 1911 the installation and surrounding reservation was auctioned off to cattlemen in the vicinity for a paltry $4,000, and Fort Bowie began its decline into limbo. Its place in history has been neglected; no other military establishment in the West did more to advance civilization in its isolated area.

Apache Pass lies off the beaten path of today's tourists who, on their way down Highway 666 to visit the fabulous Wonderland of Rocks in Chiricahua National Monument ten miles farther south, see the Pass-if they notice it at all-as an inconspicuous saddle denting low mountains on the eastern skyline.

By movie standards, Apache Pass may not be photogenic in the 3-D concept of spectacular scenery. Perhaps that is why Hollywood, in producing their perennial epics about “Apache Pass,” choose such super-colossal gorges as Canyon de Chelly to double for the Butterfield road's dark and bloody ground.

But moviedom's cameras are guilty of needless misrepresentation. Apache Pass, for all its lack of cliff-girt chasms and snow-clad crags, is scenic in a rough and sinister way-as grim a malpais in 1954 as it was to the Indian-harassed stagecoach drivers hauling adventurers west in 1854. But the menace is imaginary rather than actual; the most timid motorist can traverse the modern well-graded dirt road over Apache Pass at any season of the year in a half hour's time. Tourists entering Arizona by Highway 86 from the east frequently take the Apache Pass cut-off from Bowie, in the San Simon Valley, to Dos Cabezas Junction on the Safford-Douglas highway. It is doubtful if one visitor in a hundred sees old Fort Bowie in passing, however. The modern Apache Pass road is a mile north of the post, and the crumbling adobe ruins are so exactly similar in color to the roundabout terrain that they are difficult to spot, in midday especially, even with the aid of glasses. At dawn or sunset, however, the ruins stand out like gaunt tombstones in the distance, forming their sepulchral pattern against the sage and greasewood which stand in review on the empty parade ground and march off and away up the steep flanks of Bowie Peak. Where, ninety-two years ago, Uncle Sam built a bastion to protect the California Trail.

In motoring across Apache Pass today, the tourist should bear in mind that Butterfield's stages kept to the bottom of the canyon, being denied the easier gradient which modern bulldozers and blasting powder have gouged along the Dos Cabezas footslopes. Down there, where the chaparral grows thickest, may still be seen the twin ruts of the old Concords, scoring their enduring mark in patches of exposed bedrock. Here and there are weedy graves, some marked by century-old cairns of rock, where unknown emigrants, prospectors and soldiers were cut down by the Apaches. A few sites are marked by signs erected by the Bowie Chamber of Commerce; most of them are invisible from the road.

At one point, two miles from the eastern entrance of the Pass, a three foot cone of concreted lava stands fifty feet south of the road. Imbedded through it are two lengths of chromium-plated brass tubing. By sighting through these, the viewer sees framed the panorama of old Fort Bowie, otherwise invisible against the drab overall camouflage of the landscape. These tubes were carefully calibrated by engineers of the Arizona Highway Department to bear on 32°40′ North Latitude, 32°27′ West Longitude-the mesa 4,826 feet above sea-level The ruins of Old Fort Bowie are not for the hurried sightseer who insists on reaching historic spots without leaving asphalt. But for the student of Western Americana, for the tourist who thrills to the oft-told tales of cavalry-versus-Indians, a trek to Old Fort Bowie is a richly rewarding experience.

The easiest approach to the site is from the east, or San Simon Valley side. A straight dirt road leads south from Bowie, on US 66, for ten miles. Here the road forks, the left turning being the right-of-way to ranches in Emigrant Canyon, in the near foothills of the Chiricahuas. The right-hand fork enters Apache Pass proper, an hour's driving time to Willcox.

To reach Fort Bowie, continue another four miles on the ranch road to an unsigned fork veering right toward the looming rocky height which is Bowie Peak. This road follows a barranca for a half mile and brings the visitor to a barbed wire fence with two gates bracketing the creekbed.

The owner of jeep or jalopy can enter the right-hand gate and continue on another half-mile over an exceedingly rocky, but passable one-way lane, and reach the very sallyport of Bowie. Spiny roadside thickets discourage the entry of shiny new cars, however, whose owners face an easy twenty-minute walk to the Fort with no difficulty other than ordinary vigilance against treading on a rattler sunning himself on the road.

At this point it might be well to insert a word of advice. The serious student of Fort Bowie history should, before visiting the site in Cochise County, devote a few hours to poring over the documents and relics from the post which are kept in the Arizona Pioneers Historical Society Museum in the University Stadium in Tucson, or the archives of the Capitol Building in Phoenix.

By so doing, he can study contemporary photo-graphs showing Fort Bowie as it appeared in its heyday during the '70s and '80s, whereby individual buildings, now in ruins, can be sketched on a ground plan and later identified in si tu.

Armed with such advance knowledge, the visitor's first glimpse of Fort Bowie cannot fail to impress him with a sense of the locale's historic significance. The visible remains seem eerie after the decay of half a century's neglect; not one of the forty-odd buildings has its roof intact. Every stick of timber has long since been carted away, to reappear in Dos Cabezas, Willcox, as fence posts skirting cattle ranges, or in ranchmen's barns.

The first landmark to be encountered is the emi-grants' waterhole which was the genesis of the post. It is easily identified by the lush paloverdes and tamarisks hemming its contemporary concrete coaming. Fifty paces south of the spring is a planked-over tunnel mouth at the foot of the hill. This was Bowie's powder magazine; a signboard dating back to the '80s still warns the visitor DANGER-HIGH EXPLOSIVES!

West of the subterranean powderhouse, across a

Scene at Fort Bowie after Geronimo's surrender

Sandy-floored ravine where leather-springed Concords once jounced in from Stein's Pass on the New Mexican border, rises the stark shell of a ninety-year-old building, thirty by 156 feet, with thick adobe walls rising ten feet high. This is the largest relic to survive the onslaughts of nature's erosion and the heavy hand of the vandal. It housed the post library, a schoolroom where soldiers' children learned their 3 R's, and a bakery shop. hospital steward's cubicle, and to one side a kitchen and bathhouse.

Officers' Row followed the south boundary toward the west, each house consisting of two 15x15-foot rooms separated by a corridor, with adjoining kitchens and dining rooms. Midway along the Row we find the bestpreserved remains of Fort Bowie-a triple-compartmented concrete cistern, six feet deep by fifty feet long, which guaranteed a water supply for the Officers' Mess during drought periods.

One's imagination should be given free rein as we cross the brush-dotted parade toward the northern ruins. Yonder is the wooden stub of the flagstaff where Bowie's garrison once lined up by companies in regimental review; this is the spot where Geronimo's renegades laid down their arms in 1886 to end the threat of the Apache for all time. From Bowie the die-hard chief and his band were taken to the railroad for shipment en masse to Fort Pickens in far-off Florida.

Coming to the northwestern corner of the parade we find the dissolving adobe walls of the guardhouse and hospital. The visitor can define the outlines of a storeroom next to a nine-bed ward, followed by a dispensary, Eastward along the north side of the quadrangle are the ruins of the commissary stores warehouse, its twentyby-fifty-foot cellar nearly filled with the residue of its dissolving walls. Closing the squared circle of our tour is a barrack, divided into two equal squadrooms, with messhall and kitchen in the rear.

Here in a room where weary Indian fighters once hung up their sabers, the floor stands open to the brassy sky, with three generations of cactus and mesquite and sage growing tall. Here, amid the alluvial debris of mud walls, the visitor may chance upon a corroded brass button bearing the army's eagle, dropped from some trooper's uniform long ago. Rarest prize of all to the souvenir hunter is the copper insignia worn on a cavalryman's hat, the crossed sabers bearing regimental numeral and company letter; these have been picked out of the dust within recent months.

North of the ruins are the stone walls of the old stables and corrals. Vandals have long since carted away Fort Bowie's choicest trophies, but today's visitor should explore the brushy area northwest of the ruins, which was the old rifle target range. Here, amid the sage and rubble, corroded cartridge cases from cavalry carbines and Colt pistols are still plentiful, lying where they fell many yesterdays ago after being ejected from the weapons of troopers engaged in target practice here.

The silence that pervades the old Fort is broken today by few sounds-the drone of an airplane winging high overhead, the yammer of a coyote far back in the hills, the buzz of a diamondback or the scuttle of a whiptail lizard amid the ruins. But within the memory of persons still living, this mesa once echoed to the war whoops of ambushed redskins, the twang of bowstrings, the rumble of emigrants' wagonwheels. The ghosts of Apache Pass die hard.

In order to gain an idea of Fort Bowie's geographical environs, the visitor should climb Bowie Peak-1,248 feet to the summit where the old heliograph station stood. During the period of the Indian wars which the military might of Fort Bowie did so much to terminate, Fort Bowie's signal station was the busiest message center in Arizona Territory.

From Bowie's crest a sweeping panorama of rugged, desolate grandeur awaits the climber. Westward, beyond Helen's Dome in the near distance, we see the Dragoons and the dark cleft of mystery which is Cochise's Strong-hold, guarding the secret grave of that great Indian chief.

To the northwest of Apache Pass lifts the twin-peaked heights of Dos Cabezas Peak, a Spanish name meaning "two heads" said to have been given the mountain by the armored conquistadores of Cabeza de Vaca, the first white men to visit the region. Northeastward, the San Simon Valley stretches away to meet the purple Peloncillos and Gilas; to the east is Stein's Pass in New Mexico. Southward in the near distance is Cochise Head, a lithic profile of the chief which guards the fantastic lava formations of Chiricahua National Monument, less than ten miles away as the buzzard flies.

Descending to Fort Bowie again, the visitor can follow the dim trace of the Butterfield Stages' wheels northeast into Apache Pass. A half mile along the wash is the site of the old Military Cemetery, where the graves carried such macabre epitaphs as "Murdered by Apaches," "Tortured by Indians." When the fort was deactivated just before the turn of the century, most of the known emigrants and soldiers interred there were moved elsewhere; today only a few grave mounds can be found amid the encroaching mesquite and catclaw.

The outstanding landmark of the Fort Bowie region is the blunt-knobbed cone directly west, 6,363-foot Helen's Dome. Only experienced mountain climbers should attempt its precipitous scarps. Its inaccessibility made it useless for army signal corpsmen.

The naming of Helen's Dome is lost in legend. Some historians believe it honors the wife of a Bowie officer; but others, such as Ray Kent of the Silver Spur Ranch in the Chiricahaus, insist on the following version: In the early '50s, a California-bound wagon train outspanned at the waterhole where Fort Bowie was to be built a decade later. Apache warriors attacked the squared circle of Conestogas at dawn, firing the canvas wagon sheets with arrows soaked in deer grease and rolled in gunpowder before being ignited and dispatched.

Of the beleaguered defenders, one-a girl named Helen-managed to break through the cordon of howl-ing redskins. Her trail was picked up by moccasined braves, who followed her up the tortuous height of the nameless dome-shaped mountain west of the wagon camp. There, on its lofty crest, the girl found herself trapped. Rather than risk capture and torture-or worse, a life of slavery in some squaw's lodge-Helen flung her-self off the peak into the jagged talus 500 feet below, and her body was never recovered. Survivors of the wagon fight named the mountain Helen's Dome.

Whether this melodramatic story is fact or fiction, it is true that in 1904, the splintered skeleton of an adult female was discovered north of Helen's Dome by a prospector. Nearby was an 1848 model Dragoon percussion revolver. Four of its six chambers held powder and ball; the hammer was rusted open at full cock.

The revolver and arrowheads wound up in the pioneer historical collection of author Charles M. Martin of Oceanside, California, who in April, 1953, presented them to the writer, freshly returned from a story-hunting expedition to Fort Bowie.

Today the ruins of Old Fort Bowie bask in sun-drenched solitude, fenced off from grazing livestock but otherwise unprotected; a fast-crumbling monument to Arizona's historic past. The men whose footprints have vanished from the dust of Bowie's parade ground include the famous and infamous of the past: Cochise and his loyal friend Tom Jeffords; outlaw Curly Bill Brocius of nearby Galeyville; General Nelson A. Miles and his arch-foe Geronimo; the bronco Apache, "Big-Foot" Massai; conquistador Alvar Nuñez (de Vaca); sheriff John Slaughter, General George Crook, scouts Al Sieber and Tom Horn, empire-builder John Butterfield, pros-pector Ed Schefflin-and a host of others.

This is hallowed ground. It can be visited without undue difficulty. More the pity, then, that it should be overlooked by the cavalcade of motoring Americans, speeding across Apache Pass in search of the better-publicized wonders of the Old West to be found in such profusion along Arizona's highways.

Bill Williams Mountain Men

Although March is the month that brings the first day of spring, the Bill Williams country is not exactly synchronized with the rest of the state in the matter of the seasons. Almost every year that the ride has been made the weather has been brisk to say the least. In 1954 the bewhiskered buckos hit the trail with the morning thermometer standing at six below zero, and the ride was begun in snow and sleet storms the next two years.Despite unreconstructed horses, snow and ice, hangovers, and the many other hazards of the Mountain Men's way of life, there have been only three minor casualties during the history of the group. Ray Stewart broke a finger while mounting for the first ride in 1954, Bill Lilly did the same thing on the next ride, and Hurley Wright received a horseshoe imprint on his leg in 1957.

The Mountain Men do well by themselves in the culinary department. Typical cow camp grub-which means such things as steak, beans, and biscuits cooked in Dutch ovens-sustains them during the ride.

One departure from the true Mountain Men's wayof life can be found in the modern counterparts' sleeping equipment. There are no buffalo robes to be found in camps. Some of the men favor the warmest of modern sleeping bags and air mattresses, but most of them rely on the standard cowboy-style bedroll with a tarpaulin cover under which a man can tuck his head to keep off the frost and snow.

The first day's ride takes the men from their home at the foot of their namesake's mountain to camp on the Perkins ranch at Perkinsville on the Verde River. Five o'clock the next morning finds them combing the frost out of their beards in preparation for riding the long haul to Dewey. The third camp is at Sunset Point on the Black Canyon Highway, where the Phoenix J. C.'s and their wives are entertained with a steak dinner. The fourth camp is made eleven miles from the Curve on the Black Canyon Highway. On that night the men customarily eat dinner at the Curve and dance all night in celebration of the impending arrival at the rendezvous in Phoenix the following day.

On reaching Phoenix the men bed down at various motels near the fairgrounds, where the horses are kept, so that they can care for their mounts each day and prepare for the opening parade of the J. C. Rodeo, getting signs, furs, and other trappings ready for the big event.

The Mountain Men have won first prize in their division each of the four years in which they have entered the Phoenix Jaycee Rodeo. (Another parade first was won at the Wickenburg Rodeo in February, 1957.) Proof of the attention-commanding appearance and antics of the Mountain Men is in the amount of news space and TV coverage that is devoted to them.

After the opening parade of the rodeo the festivities begin for the group-and only rugged constitutions enable the men to survive them. Numerous TV and radio appearances, press parties, parties and dinners given by organizations and friends each afternoon and evening, visits to the Crippled Children's Hospital, and similar activities make the rendezvous time a strenuous one. These activities are in addition to the main one of riding in the Grand Entry parade at the Jaycee Rodeo each day of the performance. The Mountain Men never fail to receive the most applause of any group in the Grand Entry.

Practically the whole state has taken the Bill Williams Mountain Men as a symbol of Arizona. Persons from any town in the state will introduce the Mountain Men to visitors as "our" Mountain Men. Also, since the news pictures and film coverage fail to specify the Mountain Men's home as being in the northern part of the state, Arizona as a whole is publicized. To further this, Ralph Painter was taken along on the 1957 ride to film the entire trip for TV and to make a record film of the ride. This film has been placed in a film library for the use of any club or organization which wishes to use it.

Although the membership the membership of the Bill Williams Mountaintain Men is limited to twenty-four, there are usually three or four openings for members, the reason for which being that today even as one hundred and fifty years ago a man must have a certain ruggedness and stamina to be a Mountain Man.

Yours sincerely

IN INDONESIA: . . . Your issue concerned with "Indians of Arizona" (August 1958) interested and pleased students at the Fakultas Pertanian, Universitas Indonesia. Indonesians were surprised to discover that there are so many kinds of Indians in one state. All copies of your magazine are very popular. ARIZONA HIGHWAYS must be one of the best ambassadors our country has, because your magazine is known and admired everywhere in the world.

Frances Edney Bogor, Indonesia

REUNION IN GENEVA: . . . I thought you might like to hear about a rather unique service performed by ARIZONA HIGHWAYS last summer. Several years ago my parents made friends with a young French girl named Jacqueline Berthelot, who was studying law in the States, when she and two friends stopped at their motel in Holbrook, on their way through Arizona. She came from the region of Haute Savoie, near Geneva. Then, last spring, a young playwright named Michel Vinaver, and his wife, Catherine, who are friends of mine visited us at our ranch southwest of Holbrook. (They spent their short vacation in New York City, Mexico City, and Holbrook, Arizona, insisting that Arizona was the best part of the trip.) My parents told them about Jackie, who lived in the same region in France. Last summer they all met in Geneva, Switzerland in this manner, quoting from Jackie's letter: "... I have been very pleased to hear of you when meeting our friends of Annecy in Geneva. It was fun. We were holding the magazine ARIZONA HIGHWAYS in our hands so we could identify each other! The Vinavers told me about the very pleasant time they spent in Arizona. If only we could have seen more of it. . ."

Mrs. J. C. Jeffers Holbrook, Arizona

PARIS FASHIONS: . . . I wrote you a long letter some two months ago and left it unfinished as I was off on a long trip around Europe for the development of a patent. Trust an inventor to be the most absent minded guy that even a giddy goat could not beat, so now the letter is lost and I must start where I left which was to thank you for the splendid copies you were kind enough to send me and which were fully appreciated I can tell you. My wife and self pored over every detail. She was delighted as an artist weaver to discover the method of the Navajos for weaving their blankets. With a professional eye she immediately spotted the trick by seeing the picture of the Indian woman in front of her vertical loom. She immediately started putting it in practice and made such a beautiful model that it was taken by Christian Dior, one of the most important Maison de couture in Paris and even the world over, who will show it in his next collection. All this through ARIZONA HIGHWAYS? Isn't life a huge joke? Jean Guichard du Plessis Epernon Eure et Loir, France

DESERT TUNNEL: . . . Thank you for publishing the interesting account of Tucson's Desert Museum Tunnel Exposition in your splendid January issue. We have long awaited an article on this subject written by William H. Carr, who was entirely responsible for the conception, design and follow-through of this unique underground structure. Mr. Carr was the Founder and first Director of the Desert Museum. In one of your picture captions you have demoted a pair of ferrets to gophers. There should be gophers in the tunnel anyway. Perhaps the Museum people will take your hint! Arthur N. Pack, President Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Tucson, Arizona

AROUND THE WORLD IN EIGHTY MINUTES - AK AKVIK NIGHT FLIGHT Denver, Albuquerque, Phoenix, and the little towns between them, are glittering jewels against the black of night, red, green, yellow, crystal white. Along the Main Streets of the little towns are ropes and chains of neon lights. All the jewels of the Indian Princes, the diamonds from South African mines, a year's product from the gem cutters of Amsterdam, the hidden treasures of song and story! Borne on a magic carpet, I look down on all the treasure of the world, under the sea, under the land, in the forgotten caves of dreams. Hail Edison and the incandescent bulb and all the electricians that followed him! Main Street stretches farther and farther, and the clustered lights of the crossroads are earrings hung on the black trees of night. Denver, Albuquerque, Phoenix, you are queens wearing your jewels proudly against the blackness of this night.

-FLORIDA WATTS SMYTH DESERT MAGIC How still The desert night. A coolness rests the earth; Peace reigns. How vast its canopy of stars,

-LALU S. MONROE

BONANZA DAYS Once the town was roaring wild. In far Bonanza days From stope and tunnel Fortune smiled, Baring the shining maze Of treasure where the miner's drill Probed the mountain's thews, And Jerry Lynch rode down the hill On a horse with silver shoes. And now from ruined winze and raise The town, deserted, hears No echo of Bonanza days Or the lords of rough frontiers. For, where the Lode died, all is still Save the ghostliest of "Wahoos!" As Jerry Lynch rides down the hill One his horse with silver shoes.

-ETHEL JACOBSON MINE The night and the stars are mine, And the sigh of the wind. The carpet of grass That cushions my tread And the rustle of leaves That shelter my head Are mine, and the night's, and the wind's.

-ETHEL E. MITCHELL

OPPOSITE PAGE

SONORAN RACCOON-Procyon lotor mexicanus-The raccoon is easily identified by his black mask and ringed tail. He is found in all the Southwestern states, making his home in rough canyons and brushy bottoms near running water. The coon's track is distinctive and is said to resemble a child's footprint. The coon is omnivorous, probably preferring fish but his diet will also include acorns, berries, cactus fruits, and mesquite beans, which he relishes. Rodents and small game make up a small percent of his diet.BACK COVER BADGER-Taxidea taxus-Found throughout the Southwest, his main diet consists of rodents and occasionally a bird or bird eggs. He makes his home in burrows dug in alluvial soils. The badger is well known for his defensive weapons, which include long, raking claws, sharp teeth, and loose skin. He is usually avoided by all other predators in his territory.

MARCH, 1959

PAGE THIRTY-SIX

ARIZONA HIGHWAYS

Already a member? Login ».