Boat Trip to Rainbow Bridge

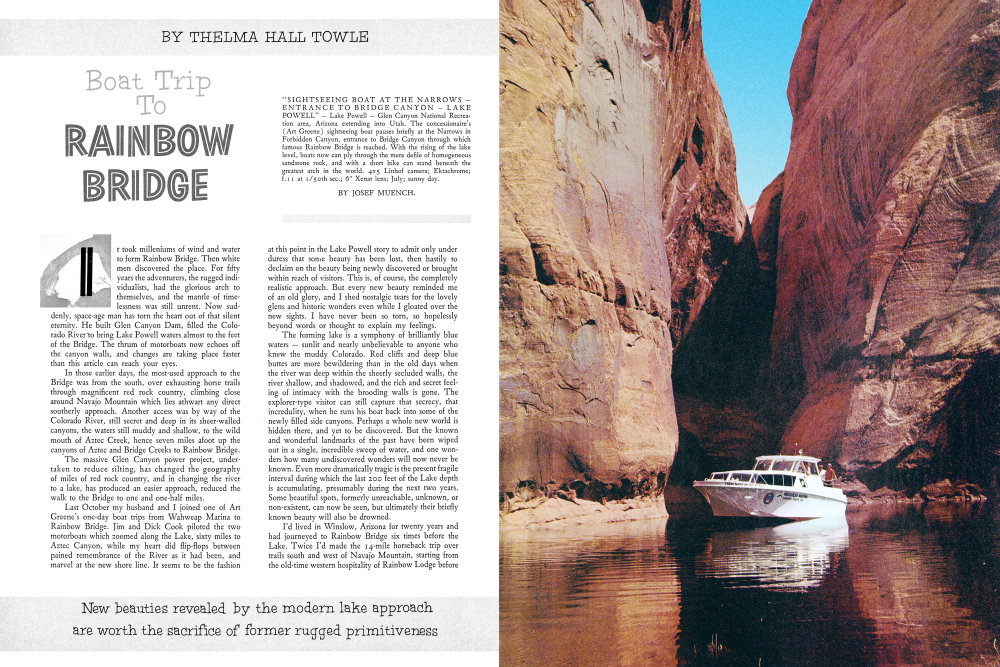

"SIGHTSEEING BOAT AT THE NARROWS ENTRANCE TO BRIDGE CANYON LAKE POWELL" Lake Powell Glen Canyon National Recreation area, Arizona extending into Utah. The concessionaire's (Art Greene) sightseeing boat pauses briefly at the Narrows in Forbidden Canyon, entrance to Bridge Canyon through which famous Rainbow Bridge is reached. With the rising of the lake level, boats now can ply through the mere defile of homogeneous sandstone rock, and with a short hike can stand beneath the greatest arch in the world. 4x5 Linhof camera; Ektachrome; f.11 at 1/50th sec.; 6" Xenar lens; July; sunny day. It took milleniums of wind and water to form Rainbow Bridge. Then white men discovered the place. For fifty years the adventurers, the rugged individualists, had the glorious arch to themselves, and the mantle of timelessness was still unrent. Now suddenly, space-age man has torn the heart out of that silent eternity. He built Glen Canyon Dam, filled the Colorado River to bring Lake Powell waters almost to the feet of the Bridge. The thrum of motorboats now echoes off the canyon walls, and changes are taking place faster than this article can reach your eyes.

In those earlier days, the most-used approach to the Bridge was from the south, over exhausting horse trails through magnificent red rock country, climbing close around Navajo Mountain which lies athwart any direct southerly approach. Another access was by way of the Colorado River, still secret and deep in its sheer-walled canyons, the waters still muddy and shallow, to the wild mouth of Aztec Creek, hence seven miles afoot up the canyons of Aztec and Bridge Creeks to Rainbow Bridge.

The massive Glen Canyon power project, undertaken to reduce silting, has changed the geography of miles of red rock country, and in changing the river to a lake, has produced an easier approach, reduced the walk to the Bridge to one and one-half miles.

Last October my husband and I joined one of Art Greene's one-day boat trips from Wahweap Marina to Rainbow Bridge. Jim and Dick Cook piloted the two motorboats which zoomed along the Lake, sixty miles to Aztec Canyon, while my heart did flip-flops between pained remembrance of the River as it had been, and marvel at the new shore line. It seems to be the fashion at this point in the Lake Powell story to admit only under duress that some beauty has been lost, then hastily to declaim on the beauty being newly discovered or brought within reach of visitors. This is, of course, the completely realistic approach. But every new beauty reminded me of an old glory, and I shed nostalgic tears for the lovely glens and historic wonders even while I gloated over the new sights. I have never been so torn, so hopelessly beyond words or thought to explain my feelings.The forming lake is a symphony of brilliantly blue waters sunlit and nearly unbelievable to anyone who knew the muddy Colorado. Red cliffs and deep blue buttes are more bewildering than in the old days when the river was deep within the sheerly secluded walls, the river shallow, and shadowed, and the rich and secret feeling of intimacy with the brooding walls is gone. The explorer-type visitor can still capture that secrecy, that incredulity, when he runs his boat back into some of the newly filled side canyons. Perhaps a whole new world is hidden there, and yet to be discovered. But the known and wonderful landmarks of the past have been wiped out in a single, incredible sweep of water, and one wonders how many undiscovered wonders will now never be known. Even more dramatically tragic is the present fragile interval during which the last 200 feet of the Lake depth is accumulating, presumably during the next two years. Some beautiful spots, formerly unreachable, unknown, or non-existent, can now be seen, but ultimately their briefly known beauty will also be drowned.

I'd lived in Winslow, Arizona for twenty years and had journeyed to Rainbow Bridge six times before the Lake. Twice I'd made the 14-mile horseback trip over trails south and west of Navajo Mountain, starting from the old-time western hospitality of Rainbow Lodge beforethe Bill Wilsons retired and the Lodge burned; then once by way of the later-more-popular trail east and north of the mountain, with Ralph Cameron jeeping us fourteen miles from his Navajo Mountain Trading Post to a certain piñon tree seemingly in the middle of nowhere, then fourteen more miles by horse. Twice I had flown over it; and once had hiked in with a Georgie White party during a lazy assault-boat trip down the Glen Canyon after the new Glen Canyon Bridge was completed but before water impoundment began.

But now our motorboats zipped past the bay which is backing up into Kane Creek, and I remembered that cold and windy Thursday when Georgie landed us there, at trip's end, and Earl Johnson waited to jeep me through Gunsight Pass back to Page. We bounced along the old cart track. The lowering sun was stretching the the black shadows across the land, and the Gunsight cliffs were pillars of brilliant gold. Earlier that day, adrift in the shallow narrows almost within sight of our Kane Creek landing, we had grounded on a sandbar for the umpteenthtime on the trip. The men, as usual, went overboard to push us off, but the bathing-suited joker of our crowd didn't climb back in. Instead he said, “The devil with this. I'm going to walk home.” And off he started, walking down the middle of the river, while the boats trailed along behind, all of us shaking with laughter at the incongruous sight of his skinny form, ankle deep in the great Colorado River, a tiny figure between overpowering walls. And now the water is several hundred feet deep over the spot.

Perhaps one of the saddest aspects of the change is not being able to identify exactly where some of the treasured landmarks now lay drowned to be so unsure of your location in your own bailiwick. We passed, seemingly in mid-lake, a National Park Service buoy marked “Rainbow Bridge National Monument.” We turned into the narrowing bay beyond, realizing that this must be the former Aztec Creek. But where lay the tiny Indian ruins which had been almost hidden in the walls at the mouth of the creek in the old days? The marvel of discovering them, the first time I rode a horse from Rainbow Bridge down to the River, lay warm against my heart. They had looked so tiny in the great walls, the spot so lonesome. It was puzzling to think of those ill-equipped Indians, wandering such endless reaches, making homes, raising and storing food. Far more personal was the time with Georgie when we sheltered from a cold, nasty rain under the overhanging cliffs, and wafted a mental thankyou to those early engineers for their clever placement of their homes. We gathered firewood from the boiling, roaring Aztec, built our supper fires in the shelter of the room walls. We hugged our fires, listening to the moaning swish of sidebanks collapsing at the mouth of the creek, and wondered if the creek would subside enough before morning so we could hike along, and necessarily in it, to the Bridge. And we slept that night inside the rooms where countless brown-skinned families had dreamed their dreams.

Now we motor-boated across the spot, and possibly also across the tops of cliffs which, on that occasion, had been the backdrop for numerous waterfalls banging off the cliffs. At motorboat speeds it was amazing how quickly we were into the narrowing canyon where our earlier party had waded the rushing stream, and further upcanyon, had ploughed through loose sand. Canyon walls began to close in on us and we banked first around a left elbow and then hard over around a right. For the first time on today's trip, that well-loved feeling of secret intimacy that was in the old Glen Canyon came welling around me. Fleeting, at this speed, and with the pulse of motors beating in one's ears I wondered how many of the new order of visitors would catch that fleeting joy.

Perhaps I still believed the Narrows would be unchanged, that the joining of Forbidden Canyon and Bridge Canyon with Aztec Creek would still be a fragile water course, with the rock-channeled Bridge Creek bath-tubbing through the twisting, slender opening of the Narrows. We were still in deep water when Jim slowed our boat, and like the crack of doom I recognized the tooth-shaped spire that closes the view into Forbidden.

On the last of those earlier trips this spot had been only a series of mud-rimmed puddles, and in one of them I'd caught the Kodachrome reflection of that spire.

Sharp on our left the slot of the Narrows was no longer the seemingly impenetrable opening of the past. It is still narrow and beautiful, overshadowed by its own cliffs running high to the sky, but it has somehow lost its unbelievable quality. Formerly its devious winding set the walls fingering into each other so it looked like a solid wall. That a narrow slot opened through to another canyon could be discovered only by a really searching eye. Now the opening is fairly obvious, not to mention that big white letters close to water level say "Rainbow Bridge," and an arrow points to the Narrows the last and horrible desecration. Our boats drifted slowly through, and I remembered having climbed the right-hand wall, one time, to the tumbled remains of an Indian lookout post where I looked down upon our horse party trailing through the winding slot. I flubbed that picture, fooled by the contrast of sunlight and styxian shadow. Now it is the picture I will never take. Just beyond the Narrows we landed against a sandbank, clambered out of the boat. Our 13-year old Heinztype dog had made the boat trip with us, and now my husband threw him over his shoulder like a sack of meal and put him ashore. The dog hiked to Rainbow Bridge with us, loose sand, heat, and all, and I'm afraid that fact alone will stand in my mind as a denominator of the change that has taken place.

Between the Narrows and the landing place was a mess of driftwood and twigs, on water slicked with oil. Whether this came from the boats that run ashore here for the hike to the Bridge, or whether there is an oil seepage in some area of the shore line is a question neither Jim nor Dick could answer. Just up-creek from our landing, a small footbridge has been constructed across the creek. This, combined with the sluggishness of the water here, resulted in a back-up of twigs, plant and tree seeds, leaves and driftwood. This entire area thus had a scummy, mosquito-breeding look which made me heartsick. We can only hope that ultimate plans of the Park Service for the Narrows (of which more later) will serve to clean up this repulsive mess, and this same condition will not reoccur at the high water level if and when the waters back up into the subcanyon within sight of the Bridge.

The Rainbow Bridge itself is still unchanged. As yet it shows no mark that thousands now reach it to the hundreds who formerly came. One's first sight of it is still that surprise glimpse of the free end of the arch peaking coyly from behind the curving walls, like water pouring from the snout of a pitcher, petrified for all time. Navajo Mountain still makes a dim blue backdrop. A book still reposes under the arch in which one may register, though we were glad to learn that the old book, when visitors earned their right to register the hard way, has been taken to Monument headquarters to become part of Bridge memorabilia. On this trip there was no time for the climb to the

"HIKERS APPROACH RAINBOW BRIDGE" BY JOSEF MUENCH. Rainbow Bridge National Monument, Southern Utah, is located in Bridge Canyon only a little over a mile hike from the edge of Lake Powell, formed behind Glen Canyon Dam. Hikers pause in awe as they get their first full view of this "Rainbow in Stone." Under its 309 foot height, the Capitol in Washington could be placed with room to spare. The photographer has hiked a total of seventeen times to view this marvel of Nature and to stand beneath it, only to feel the smallness of Man. In the background, Navajo Mountain wears a mantle of spring snow. 4x5 Linhof camera; Ektachrome; f.16 at 1/50th sec.; 6" Xenar lens; April; sunny day. top of the arch, and perhaps this particular side trip will continue to beckon only the hardy and adventurous. Jim said the two ropes which formerly had been the key to getting onto the Bridge top have been removed as a safety measure, which certainly is a warranted precaution. I've been up there twice. It is an eery perch to say the least, but the views afforded, both from the top of the great arch and from the slick-rocks enroute, are superlative. Somehow unexpected are the curious angles from which one sees the Bridge, making it appear even less believable than when seen from the ground. Even this trip developed one new treasure to add to my collection of Rainbow Bridge memories. John Wetherill, who is credited with being the first white man to reach the Bridge, and who visited it many times thereafter, had told that on one trip in 1909 a sudden storm blew up and he sheltered under a rock close to the Bridge. He whiled away the wait by pecking his name on the rock. Zane Grey, who had first been to the Bridge with Wetherill, made another trip in 1911 and added his name near Wetherill's. Bridgeophiles have since spent days searching for those signatures, but it was not until recently they were found, and Jim took us to them. As yet no one has desecrated them by adding his own, but my heart said, "How long?" In the subcanyon beneath the Bridge, Jim and Dick had spread a fried-chicken-and-sandwiches lunch on a flat rock. Water dripped from ledges in the wall, and red monkey flowers clung head down from the roof. On shelves below, an array of tin cans stored the tinkling drops for thirsty hikers. The amazement of our companions at this simple expedient pointed up the fact that it is a completely new segment of the population which is now seeing this no-longer-remote world. I recalled that on one of my earlier trips, as chaperone for a group of college youngsters, we'd spent the scorching afternoon hours swimming in a shallow pool almost directly under the Bridge. Floating on the surface, we'd tipped our heads back and back until the Bridge came into view, upside down, over our heads. By some optical illusion, the Bridge seemed to be in motion and settling down upon us; momentarily rather terrifying. Some freshet in the meantime has washed out the natural dam that caused that pool.

PHOTOGRAPHS BY DOROTHY AND HERB MCLAUGHLIN

This had to be the end of this trip, but as we ate I wondered if anyone would still make the long horseback rides through the beautiful canyons from the south. Those long miles are exhausting for amateur horsemen, but they are a golden experience, and it is here that the massive timelessness, the deep silence, will still be found unbroken. On the eastern trail from Cameron's there is remote Owl Bridge, and as the trail circles north of Navajo Mountain it traverses close to superb white spires and contorted cliff faces that hide the upper dome of the mountain, the sacred Nat-sis-an of the Navajo Indians. On the western trail, very little used since Rainbow Lodge burned, is one view which is literally unforgettable. The trail slabs high onto a shoulder of the mountain, then plunges two thou sand feet to the floor of Cliff Canyon. From the high point on the mountain one sees the whole world spread out, a valley-of-the-moon scene in exaggerated Kodachrome, limitless and unreal, a rumpled rock wilderness, rose and pink, red and brown, rounded and domed like frozen ocean billows. The scene is enveloped in absolute quiet. Not the quiet of nature at peace, but the unfamiliar quiet of an enormity of space, embraced in utter silence. There must be life in all that rugged country, yet somehow one seldom sees it, and standing there, one wonders if Eternity is something like this.

On this trail, too, is a weird Disney-world of rock formations: Indian cheiftains, hobgoblins, and elephants' heads that seem to march along the canyon wall, keeping an eternal eye on you. There is an arch in Cliff Canyon. Whether this has a name I do not know, for it seems always to be spoken of simply as "the arch in Cliff Canyon." It is much the shape of Rainbow, though not separated from its cliff matrix, only the nearest slit having broken through between arch and wall.

Wahweap marina

A whoop and a holler from the arch, one rides into the narrow defile between red, ,towering cliffs that forms the opening into Red Bud Pass. At first the easy floor winds between walls so close that a heavily loaded pack horse almost rubs on both sides. Then the corridor changes into a nightmare of loose dirt and broken rock up which the animals claw in a desperate scramble that leaves one conscience stricken to be still mounted. But walking is no better, for you slip back one step for every two for ward. At the apex of the pass, squeezed in by deep shadow and gloomy red cliffs, you look out into brilliant sun, highlighting a stark white mountain beyond the pass. Those trails are long and wearying for both man and horse, necessitating an overnight stay near the Bridge. Both the Wilsons and Camerons used the shelter near the arch afforded by a great shallow cave. A large waterhole and spring, a couple of chuck boxes, a permanent fireplace, a few cast iron frying pans and dutch ovens, a few cots made a simple camp, but it seemed palatial at the end of those 14-milė horseback trips. Just before camp is reached there is another "first view" of Rainbow Bridge a completely different first view from that seen when approaching from the Lake. Neither is it what one has expected. The trail, which has been in the creek bed for some miles, climbs out along the right wall, while the creek elbows off to the left. The walls reach upward probably a thousand feet, softly sheer, in many shades of rose depending upon the sunlight or shadow. About a third of the way up, a gracefully curv ing span, is the Rainbow, in this view looking much more a bridge than a rainbow, for the bowed ends are behind the enclosing walls. For enormous size one has been prepared (309 feet high, 278 foot span) by the pictures one has seen. But here in its own setting, as part of its own environment, it is dwarfed into disproportion. It is the surprise element one always remembers. One came to

"ON WAY TO RAINBOW BRIDGE FROM LAKE POWELL" Lake Powell Glen Canyon National Recreation area, Arizona extending into Utah. View is in Bridge Canyon, between the lake and Rainbow Bridge, a distance of a little over a mile. Three hikers rest briefly along the creek which has its source high up on Navajo Mountain and passing underneath Rainbow Bridge before joining Lake Powell. It is quite an experience to wander along this little insignificant stream, which over eons of time has cut this tremendous canyon between red sandstone walls. 4x5 Linhof camera; Ektachrome; f.16 at 1/50th sec.; 6" Xenar lens; April; sunny day. "IN NARROW CONFINES OF FORBIDDEN CANYON - LAKE POWELL" Sightseeing boat in Forbidden Canyon on its way to Rainbow Bridge. Formerly a strenuous hike of six miles between river and bridge, boats now can move up this canyon to within a short distance to view and stand beneath the "Rainbow in Stone." 4x5 Linhof camera; Ektachrome; f.12 at 1/100th sec.; 6" Xenar lens; July; sunny day.

see the Bridge, yet in this view the canyons and the walls dominate, not the arch. The Bridge is like a small but perfect jewel, enhanced by a massive setting.

On our return down the Lake, Jim and Dick made two short side trips into canyons newly filled to levels that revealed new wonders. In the first was a great cave, beautifully arched, called Cascade Canyon Amphitheater. They drifted the boats in, and our faint hellos echoed and reechoed from the roof and opposite walls. Most charming, though, was a peculiar lighting effect on a slightly overhanging rock face at the cave entrance. A smooth tan surface reflected flickering light from the water, like the rippling hide of a skulking leopard. The dappled gleams shivered and shimmered. The boatmen called it "Fire of the Dancing Waters," a perfect name indeed. The tragedy is that the appealing sight is at surface level, so a water rise of fifty feet or so is going to cover it, and the ultimate rise of 200 feet will also fill the cave to a point that boats will not enter it.

Our second side trip was into Cathedral Canyon. Here an arch has long been known, formerly high above the canyon floor. In River days, hikers made the hot hike up the narrow canyon to see the perfect little arch high above their heads. Our boat entered the canyon, the walls closed in around us. The beautiful arch came into view at water's edge, so close it seemed we could touch it, a perfect half-circle, separated from but still backed by its matrix wall. And on that wall, under the shelter of the arch, a garden of maiden hair fern and greenery hung, cool and precious in the desert land. The delight which came to all of use was very real. Real, too, was the heartbreak that followed when we visualized that awful two hundred feet or rise covering the lovely arch. Rainbow is majestic in its perfect shape magnificent size, and its setting. This, the arch in Cathedral Canyon, is jewel-like in its equally perfect shape, and the charm of its green garland of ferns makes you want to reach out and hold it in your arms.

On that note of heartbreak, we returned to the Lake and zipped back to Wahweap, where there was one more thing to see. I spoke earlier of Park Service plans for the Narrows which I hoped would clean up the driftwood and scummy water surface there. On the Lake side of the Narrows, the Park Service plans to erect a float-ing ranger station. Long walkways will extend from houseboat living quarters for the staff to visitor and docking facilities for twenty boats initially, with possible expansion to fifty or more. The fueling dock, public restrooms, a concessioner's store, and lunchroom, all will be floating. No overnight accommodations are proposed because of lack of space. Another floating walkway will lead through the closed-walled Narrows to a trail to Rainbow Bridge over a series of surface and floating walkways.

At Wahweap, in a cove behind the dock, we found the entire complex, walkways, floating docks with buildings on them, and the houseboats, already constructed and ready to be floated up the Lake to the Narrows and put in place, probably after spring runoff in 1965. The contrivances are well constructed, but utilitarian in the extreme, and certainly are going to add nothing to the beauty of that pool which mirrors the peak in Forbidden Canyon, and the Narrows. I acknowledge that with so many people passing through to the Bridge, a facility of some sort is an absolute necessity. In any case, it is a fact accomplished, and all our regrets over lost beauties have come too few and too late.

Strangely, my thoughts about this trip to the Rainbow via the Lake are crystalizing more and more around something which happened at lunch under the Bridge. A get-acquainted chat, which had started while boating up the Lake, was taken up again. We learned that of our eleven members, only my husband and I had been here before. One woman had yearned for years to see the Bridge, but her husband and family insisted she was not physically up to the trip, and she quite agreed. Even with the hike reduced to one and one-half miles, all were dubious, but she put in a do-or-die vote. It had been hard for her. She trailed far behind the rest of us, but she got there. When lunch was first spread she was too exhausted to eat, but rest revived her, and the glow of her happiness in the sight of the great arch which she had expected never to see reflected on all of us. If nine people who would not have seen Rainbow Bridge under the old circumstances can now see it, and if one out of those nine is as elated as she, then I and others who so deeply regret the changes can certainly feel the sacrifice of primitiveness has been in a good cause.

Park Service's development plan

Already a member? Login ».