Hidden Enchantment of Cibecue Creek

Steeped in the colorful history of the Apaches, Cibecue Creek cuts a wilderness swath between unspoiled canyon walls for forty-five miles in one of the most primitive areas of Eastern Arizona. Its secretive journey passes ancient Indian ruins, clusters of bear-grass wickiups, virgin stands of ponderosa and oak, and multihued cliffs unmatched in brilliance and natural splendor.

The dense forest and foreboding canyon guarding this shy mountain stream abounds with bear, lion and other game species, while her crisp waters hold good numbers of brown and rainbow trout.

Near the Apache village of Cibecue where a diminishing few tribal members still follow the pagan beliefs of the medicine man Cibecue Creek's heart is diverted into a crude system of irrigation canals, which help nourish meager fields of Indian corn.

But below this picturesque Apache settlement, the wilderness recaptures the stream, squeezing it through a narrowing defile that grows tighter each mile nearer its juncture with Salt River Canyon.

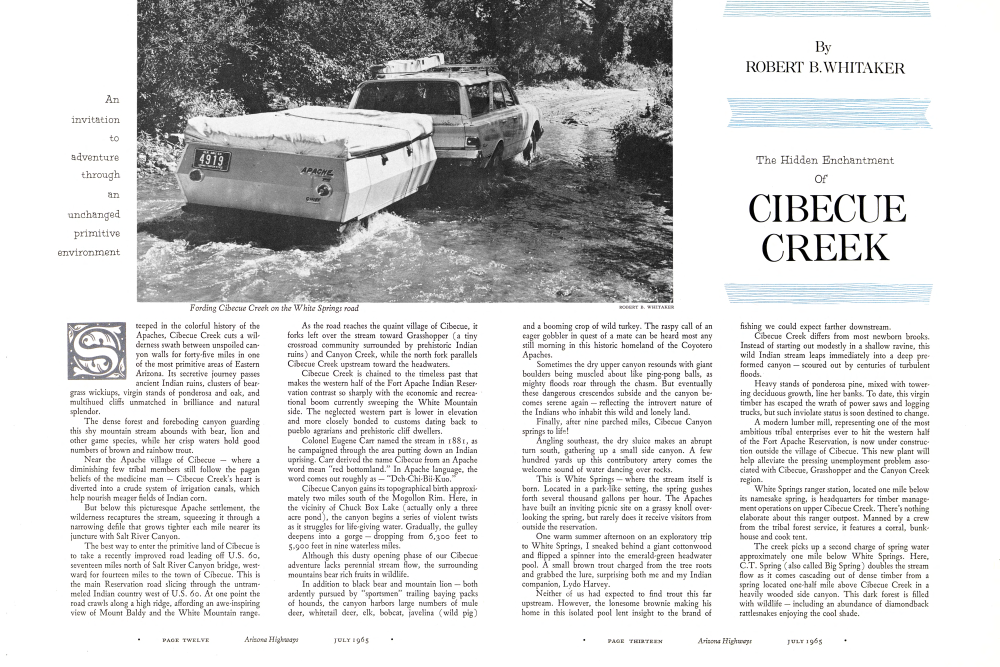

The best way to enter the primitive land of Cibecue is to take a recently improved road leading off U.S. 60, seventeen miles north of Salt River Canyon bridge, westward for fourteen miles to the town of Cibecue. This is the main Reservation road slicing through the untrammeled Indian country west of U.S. 60. At one point the road crawls along a high ridge, affording an awe-inspiring view of Mount Baldy and the White Mountain range. As the road reaches the quaint village of Cibecue, it forks left over the stream toward Grasshopper (a tiny crossroad community surrounded by prehistoric Indian ruins) and Canyon Creek, while the north fork parallels Cibecue Creek upstream toward the headwaters.

Cibecue Creek is chained to the timeless past that makes the western half of the Fort Apache Indian Reservation contrast so sharply with the economic and recreational boom currently sweeping the White Mountain side. The neglected western part is lower in elevation and more closely bonded to customs dating back to pueblo agrarians and prehistoric cliff dwellers.

Colonel Eugene Carr named the stream in 1881, as he campaigned through the area putting down an Indian uprising. Carr derived the name Cibecue from an Apache word meaning "red bottomland." In Apache language, the word comes out roughly as - "Dch-Chi-Bii-Kuo."

Cibecue Canyon gains its topographical birth approximately two miles south of the Mogollon Rim. Here, in the vicinity of Chuck Box Lake (actually only a three acre pond), the canyon begins a series of violent twists as it struggles for life-giving water. Gradually, the gulley deepens into a gorge dropping from 6,300 feet to 5,900 feet in nine waterless miles.

Although this dusty opening phase of our Cibecue adventure lacks perennial stream flow, the surrounding mountains bear rich fruits in wildlife.

In addition to black bear and mountain lion both ardently pursued by "sportsmen" trailing baying packs of hounds, the canyon harbors large numbers of mule deer, whitetail deer, elk, bobcat, javelina (wild pig)

ROBERT B. WHITAKER The Hidden Enchantment Of CIBECUE CREEK

and a booming crop of wild turkey. The raspy call of an eager gobbler in quest of a mate can be heard most any still morning in this historic homeland of the Coyotero Apaches.

Sometimes the dry upper canyon resounds with giant boulders being muscled about like ping-pong balls, as mighty floods roar through the chasm. But eventually these dangerous crescendos subside and the canyon becomes serene again reflecting the introvert nature of the Indians who inhabit this wild and lonely land.

Finally, after nine parched miles, Cibecue Canyon springs to life!

Angling southeast, the dry sluice makes an abrupt turn south, gathering up a small side canyon. A few hundred yards up this contributory artery comes the welcome sound of water dancing over rocks.

This is White Springs where the stream itself is born. Located in a park-like setting, the spring gushes forth several thousand gallons per hour. The Apaches have built an inviting picnic site on a grassy knoll overlooking the spring, but rarely does it receive visitors from outside the reservation.

One warm summer afternoon on an exploratory trip to White Springs, I sneaked behind a giant cottonwood and flipped a spinner into the emerald-green headwater pool. A small brown trout charged from the tree roots and grabbed the lure, surprising both me and my Indian companion, Lydo Harvey.

Neither of us had expected to find trout this far upstream. However, the lonesome brownie making his home in this isolated pool lent insight to the brand of fishing we could expect farther downstream.

Cibecue Creek differs from most newborn brooks. Instead of starting out modestly in a shallow ravine, this wild Indian stream leaps immediately into a deep preformed canyon scoured out by centuries of turbulent floods. Heavy stands of ponderosa pine, mixed with towering deciduous growth, line her banks. To date, this virgin timber has escaped the wrath of power saws and logging trucks, but such inviolate status is soon destined to change.

A modern lumber mill, representing one of the most ambitious tribal enterprises ever to hit the western half of the Fort Apache Reservation, is now under construction outside the village of Cibecue. This new plant will help alleviate the pressing unemployment problem associated with Cibecue, Grasshopper and the Canyon Creek region. White Springs ranger station, located one mile below its namesake spring, is headquarters for timber management operations on upper Cibecue Creek. There's nothing elaborate about this ranger outpost. Manned by a crew from the tribal forest service, it features a corral, bunkhouse and cook tent.

The creek picks up a second charge of spring water approximately one mile below White Springs. Here, C.T. Spring (also called Big Spring) doubles the stream flow as it comes cascading out of dense timber from a spring located one-half mile above Cibecue Creek in a heavily wooded side canyon. This dark forest is filled with wildlife including an abundance of diamondback rattlesnakes enjoying the cool shade.

Jim Spinks, manager of White Mountain Recreation Enterprise; Dewey Lupe, Apache game warden; and I had a close call with one of these poisonous critters while exploring the upper end of C.T. Spring.

Dewey was leading our petal up a Esint path, when a full-grown rattler - with no warming shaks of his tail - lashed out at the Indian guide. Venom splattered his trouser leg, but the snake's deadly fangs missed their mark. Sparks polished off the husky reptile with a wellplaced head shor from his .357 revolver.

The fact that xattlesnakes sometimes strike without werning should be kept in mind by all who explore Cibecue and sirallar make infested areas.

As the crisp flow of C. T. Spring blends into Cibecue Creek, the wilderness stream gains full maturity. Now her current tambles, over rocky riffles, swids through waist-deep pools, spills over picturesque waterfalls, and spreads ous behind timber impediments and primitive Indian danss. This beautiful stretch of water in a haven for fat brown trout.

Securely hidden beneath undercut embankments, bruising-big brownies patiently await insects, frogs and other unfortunate cremures to come drifting past ther dons. Occasionally, they dert out to chew up a field mouse that makes the fatal mistake of falling into the creek.

Several trout in the five and six pound class have been taken from this prime water, with the record a hook jawed eight pounder, Despite repeated washouts, Cibecue continues to maintain a self-sustaining brown trout population through natural reproduction partly because brownies are diff cult to catch, and partly because the stream is underfished.

Trout once were considered taboo by the Apaches, who classed them with Heeds and snakes. But modern red men have dropped their ancestral fears and are taking up fishing both for food and sport. This added angling pressure has prompted the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife to supplement the native brownies with twa plants of rainbow wont during the busy summer season: Indians generally follow the hatchery tuck in quest of the easily-caught rainbow, but interest wanes as these plants are harvested, and gradually the Apaches hang up their tackle and return to the fields.

As solitude again grips Cibecue Creek, big browns emerge from their protective hideouts to sortie in search of food. It is during such quier spells that many expert fly fishermen and other adasirers of brown frour travel to Cibecue to challenge this worthy adversary.

But fishing isn't the only rewarding pastime to be found on upper Cibecue Creek. Amateur archeologists with a yen for exploration will enjoy searching the sur rounding canyon walls and mesas for signs of prehistoric Indian life. The fertile valley through which the stream flows offers ideal terrain that gives evidence of having been long under cultivation.

Boyd Knapp, trading post operator at Cibecue, claims pueblo ruins can be spotted on practically every promi nent rise, with an abundance of artifacts scattered over the ground, many still intact.

Some of the finest examples of early Indian culture in the Southwest are found west of Cibecue near Grass hopper and in Oak Creek (not to be confused with popular Oak Creek Canyon below Flagstaff.) A crew of University of Arizona archeologists excavating close to the tiny Grasshopper community recently unearthed several large stone pueblos. The size of the ruins prove that heavy populations of peaceful people once farmed the region.

Most of these pueblo ruins are linked to the era from 1250 to 1350 A.D., when a combination of warlike predator tribes and severe drought finally forced abandonment of the Cibecue and Canyon Creek pueblos.

These early pueblos apparently were heavily influenced by the Hohokam culture, and perhaps to a lesser degree by the Mogollon and Anasazi peoples.

One outstanding pueblo is located close to the road at Grasshopper. A large room, approximately forty feet square, has been completely excavated, with a round kiva also well defined.

Prehistoric pottery in the Cibecue area is of a distinct type, labeled "Cibecue Polychrome." It is represented by bowls and jars, with smoke blackened insides and outer surfaces painted in color patterns ranging from red through browns, grays and blacks. The jars are quite small, characterised by blunt, slightly flaxing necks.

To the west of Grasshopper some eighteen miles from Cibecue Creek is found an amazingly well-preserved cliff dwelling. The two-story sticture, which originally contained more than zoo rooms, is lodged beneath a protective sandstone overhang in upper Oak Creek Canyon (try).

Canyon Creek ruins, as the ancient structure is called, was constructed in the latter eleventh century by a peace ful tribe of soil tillers. A stream apparently fowed in front of the dwelling during this period, affording ample inigation water for fields of dwarf Indian corn - the pri mary substance of their diet.

The superb trout waters on upper Cibecue Creek continues for eight miles, becoming less productive as it nears the village of Cibecue. A dirt road parallels that stream most of this distance, providing easy access to fishing holes and several secluded campgrounds hidden back in the timber.

Few cars travel the road because most Indians sell walk or ride horseback. The trail maanders like a wooded comatry lane, crossing the streams four times between Clbenue and White Springs. Although rough in spots, the Cibecue-White Springs road normally is passable to pas senger cars.

Apache squaws dressed in colorful skirts can be seen along the road gathering acorns, walnuts, wild grapes, roots and herbs - all important native foodstuffs. Others out for a daily stroll are carrying contented bables in cradle boards.

But, while the women walk, the men ride horseback. There are white-faced cattle to drive, deer to hunt, and friends to see. And, occasionally, the Indian men join to teast one another with a native tonic called ""Tuloksi."

Hub of Indian activity for the vast western half of the Apache Reservation is the quaint village of Cibecue. Practically every home features a wickiup and ramada, as the various Cibecue clans hold to the customs of their forebears.

The town has a population of about 800 Apaches and thirty white government workers and missionaries. The Cathelic, Lutheran and Mormon faiths are estab lished here, plus two independent churches. Cibecue has two trading posts, a government-operated day school (soon to become a public school), and a jail-but no veloons.

Cibecue, which looks little different today than it did a quarter-century ago, has been slow developing. But

PHOTOGRAPHS FOR THE FOLLOWING COLOR FOLIO WERE TAKEN AT VARIOUS TIMES DURING JUNE, JULY, AUGUST AND SEPTEMBER OF LAST YEAR. THE PHOTOGRAPHER USED TWO CAMERAS: A ROLLEIFLEX E2 AND A BRONICA 5, BOTH WITH EKTACHROME. LENS USED WERE: SCHNEIDER XENOTAR 3.5 AND A NIKKOR 50MM WIDE-ANGLE 3.5. THE PHOTOGRAPHER, WHOSE SPECIALTY IS SEEKING OUT THE OUT-OF-THE-WAY SCENIC AREAS OF ARIZONA, PREFERS THE LIGHTER CAMERAS BECAUSE THEY MAKE IT EASIER TO EXPLORE ROUGH, ARDUOUS AND RUGGED TERRAIN.

"C.T. SPRING RUSHES TO JOIN CIBECUE CREEK"

This rushing little tributary cascades down from C. T. Spring and enters Čibecue Creek about one mile below White Springs Ranger Station. It can be reached by taking the primitive road out of Cibecue village approximately nine miles due north. The water from the spring is icy cold.

"RED CLIFFS ADD LUSTRE TO CIBECUE CREEK"

A gentle riffle swirls beneath a red-rock ledge along upper Cibe-cue Creek. This scene was taken about four miles below White Springs, near the road that follows the stream north from Cibecue village. This is good trout water for skilled anglers who can cast beneath low-hanging limbs and outwit the wary brown trout. Several fine campgrounds border the stream near this point.Cibecue Creek gains its birth from White Springs, located in a park-like setting eleven miles north of Cibecue vil-lage. Although Cibecue Canyon starts near Chuck Box Lake below the Mogollon Rim, it flows dry for nine miles before reaching White Springs.

"WHITE SPRINGS HEADWATERS OF CIBECUE CREEK"

Cibecue Creek gains its strongest boost from C.T. Spring, situated in a wooded glen about one mile west of the creek. The dense forest abounds in deer and other wildlife species. The spring can be reached by hiking up a faint trail below White Springs Ranger Station. Crisp waters bubbling from C.T. (or Big) Spring help keep Cibecue Creek cool and "trouty" during the long, hot summer months. The forest is green and lovely, with few scars from timber cutting.

"ALONG UPPER CIBECUE CREEK" Cibecue means "red

"bottomland" in Apache language. The stream was well-named, as is indicated by this high bluff hanging over the beautiful mountain stream. The picture was taken close to the road leading from Cibecue village to White Springs. Red rock cliffs border the stream through much of Cibecue Creek's initial journey.

tain stream. The picture was taken close to the road leading from Cibecue village to White Springs. Red rock cliffs border the stream through much of Cibecue Creek's initial journey.

Cibecue Creek makes a sweeping bend near one of the scenic campground areas along the road to White Springs. The photographer says: "This is my favorite pool on Cibecue Creek. Although not particularly loaded with trout, it is a quiet, restful setting.

Part of the charm of Cibecue Creek is the primitive Apache homes you pass following the road to White Springs. This picture was taken on a high plateau just above the little town of Cibecue. The Apaches still live much as they did during the days of the Indian wars. Typical Apache dwellings are the wickiups (shown here) and wood-frame ramadas used for cooking and outside sleeping in hot weather.

Indian horsemen riding to town on the White Springs road. This scene was taken on the plateau that overlooks the quaint Apache village. Several Apache families live close to the White Springs road. The people are shy, but friendly. In the distance (looking upstream).

A wilderness view of Cibecue Creek looking upstream from near one of the forest campgrounds along the White Springs road. Brown trout lurk in spots like this where fallen trees and brush afford protection from fishermen and other predators.

This picturesque valley scene was taken a few miles north of Cibecue village on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation.

Afternoon storm clouds are gathering over upper Cibecue Creek as they commonly do during August.

"CANYON CREEK RUINS WEST OF CIBECUE CREEK"

Canyon Creek ruins actually is located in Oak Creek Canyon (dry) about eighteen miles west of Cibecue Creek. The secluded ruins can only be reached after a strenuous mile-long climb at the end of a rugged jeep road.

"GREEN FIELDS IN CIBECUE VALLEY"

The Apache Indians have turned to farming for their livelihood in fertile Cibecue Valley. Small plots of corn grow in open fields bordering the stream from below the village all the way to White Springs. Corn is picked by hand by the Indians. Besides its use as a food staple, the Apaches sometimes distill corn into a native alcoholic tonic called "Tulakai."

"IRRIGATION CANAL FOR INDIAN FARMS"

An Indian water diversion dam located three miles above Cibecue village. Here the Apaches have constructed a crude rock-filled dam to divert water into a primitive irrigation ditch for nourishing cornfields and other crops.

Fast-water riffle between Cibecue village and White Spring. The stream flows clear and full most of the summer, with dancing waters caressing visitors to sleep in tiny campgrounds along the pretty stream. Cibecue Creek is characterized by deep pools between long riffles. The primitive road along the stream becomes impassable to cars during rainy spells.

LAST PAGE OF FOLLOWING COLOR PORTFOLIO "NEAR WHERE CIBECUE CREEK JOINS SALT RIVER"

The majestic beauty of lower Cibecue Creek about one-half mile above its juncture with Salt River. This spot can be reached by taking a dirt road west just after U. S. 60 crosses Salt River Bridge in Salt River Canyon. It is approximately five miles down the road to Cibecue ford.

now the road leading from U.S. 60 to this small village is being paved, and a large lumber mill is being con-structed on a hill overlooking town.

The mill will provide some fifty Apaches with much-needed work, thus helping to stimulate the economy of the Cibecue region. It also should help stop the migration from Cibecue to more productive labor areas on the White River-Fort Apache side of the reservation.

"We anticipate lots of changes for Cibecue during the next decade," prophesied Boyd Knapp. "The town is entering a transition period that should open up development of lumber, recreation, grazing and farming."

There is little doubt that this vast region is on the move. Even the older Indians living in smoky wickiups feel the pulse of excitement. This is evidenced by the sad decline in native basket making, long a treasured custom of the Apaches, but now rapidly becoming a forgotten art. There now are only two or three Indian women weaving the beautiful and intricately designed Apache baskets, observes Knapp.

Apache baskets are woven of willow in a finer weave than the yucca and devil's claw type of the Papagos. Most common color combination is black and white. One of the more representative baskets of the Apaches is covered with melted pinyon pitch to hold water. Many Cibecue Indians still are seen carrying these traditional water casks.

Despite the fact that many Indians are forsaking ancient ritual for the white man's ways, certain tribal ceremonies continue unchanged from the days when Apaches rode rampant over the Southwest.

One of the most beautiful ceremonies is the Sunrise Dance. This is the official "coming out" affair that recognizes the change in a young girl from adolescence to womanhood. The Sunrise Dance generally is held when the girl reaches age twelve, but it may be delayed if the family is unable to finance the costly ceremony. Normally Cibecue hosts two or three such dances during the summer.

Several local citizens of Cibecue have illustrious ancestors who gained notoriety during the bloody Apache wars. One such person is Elaine Duryea, who helps out at Knapp's Trading Post. She is the great granddaughter of Jacob Peaches the famed scout responsible for Geronimo's capture.

Peaches, who was named by Army troopers for his friendly "peaches and cream" smile, scouted for General Crook. Captured by Geronimo, Peaches befriended the fanatic old chief in order to gain freedom. He finally escaped, eventually making his way back to rejoin Crook's forces. Peaches then was able to lead Army troopers straight to Geronimo's hideout in Old Mexico where the rebellious chieftain surrendered.

A short distance below Cibecue village is the spot where the "Cibecue Massacre" took place.

The story goes that a local medicine man named Nockedaklinny (who reputedly was inspired by Geron-imo) aroused the passions of his warriors by getting them drunk and priming them with promises that he would resurrect their dead chief, Diablo.

In August, 1881, Nockedaklinny and his fired-up braves went on the warpath. With the guiding help of several traitorous Indian scouts, he caught Colonel Eugene Carr and his column of eighty-five troopers in an ambush.

Carr pulled back with losses, but eventually re-turned to put down the insurrection. Three of the treacherous scouts were hung at Fort Grant for their part in the massacre.

As a result of the Cibecue skirmish, orders came down from Washington to step up action and end once and for all the Indian problem in the Southwest.

Cibecue Creek loses its wilderness tempo as it glides past "urban" dwellings and out into a wide valley.

As it leaves town, the stream uncoils through several miles of fertile land, much of it under cultivation. But soon Cibecue Creek grows wild again, as it plunges into the final chasm before meeting the Salt River. The canyon walls tower higher and higher, and the stream bed changes character from gravel to rock gaining new momentum through constriction.

Having gained its unleashment from Indian irrigation the stream seems to be searching for new freedom. Four miles above its mouth the creek tumbles over its mightiest falls a 40-foot drop that presents an impenetrable bar-rier for downstream fish. An occasional brownie gets washed into the deeper holes, but the tepid water in these sterile downstream pools can't be relied on to provide a fishery.

Few streams climax their journeys amid such spectacular scenery as does Cibecue Creek. With sheer walls rising a thousand feet on either side, the stream rushes headlong into the spectacle of Salt River Canyon.

Its final contribution toward preserving the Indian wilderness is to wash out the one-way road winding along the north bank of the Salt at the bottom of the canyon. A few yards beyond this dangerous ford, Cibecue's waters dissipate into the powerful werful Salt River.

Two reflections are gained in looking back upon the fascinating land of Cibecue. First, there is the undeveloped potential in cattle, lumber, farming and recreation that smoulders like a giant powder keg waiting for some enter-prising spark. This is the viewpoint that is changing Cibecue into a "Valley of Promise."

The second view is of a primitive Indian clan desperately clinging to ancient customs and beliefs in a last-ditch struggle to resist the exploitive culture of the white man.

Although my economic senses tell me to praise the first view, my emotions lament the loss of those cherished traditions of a proud people. They remind me that here is a land, rich in history and legend, where new generations still can see one of America's great Indian tribes living in much the same environment that existed generations ago.

Cibecue today looks little different from those days-three-quarters of a century ago-when cavalry hoofs clat-tered across its rocky stream bed hot on the trail of Nockedaklinny and his band of renegades.

Already a member? Login ».