DESERT GARDEN

Much of his consultation during the pre-planning stage was with Professor Franklin J. Crider, then the head of the University of Arizona's Department of Horticulture. Later, in 1926, Professor Crider was to become the director of the Arboretum, and was to be in charge of the organizational work of completing the garden, as well as the research being carried out. He spent many years in this work at the Arboretum. Dedicated in April, 1929, the Arboretum was showing results of work already being done in the study, improvement and preservation of both indigenous and introduced plants, in an effort to utilize them more fully. Research on the Simmondsia chinensis, or jojoba, was among the studies in the Arboretum laboratories, with the discovery of enormous possibilities in this particular plant, native to the Arizona and California deserts. Findings in this field showed the jojoba to have properties very useful in floor waxes, plastics, and in lubricators for high speed machinery. It was also found to be an important ingredient for hair oils. Plants such as apricot trees were set in planters where the root growth could be closely observed, bringing about the discovery that the roots of these trees did not, as had previously been supposed, lie dormant during the entire winter season. Instead, there was a period of approximately fifty-four days of dormancy, followed by new root growth during the balance of the winter, until the plant seemed to awaken and begin its above-ground growth in the spring.

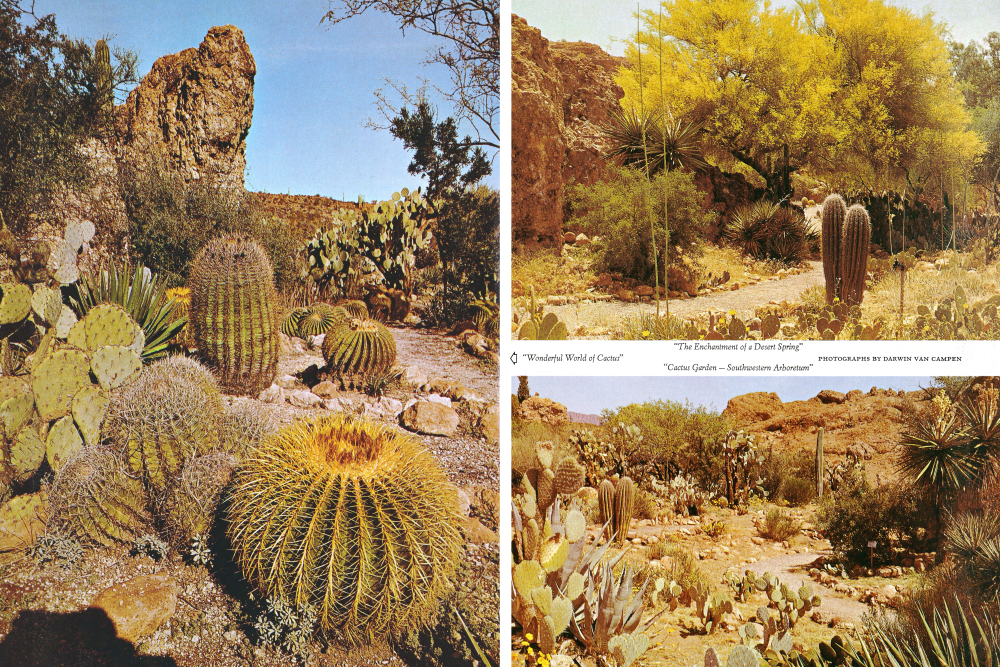

Seeds from numerous plants have been exchanged with botanical gardens, arboretums, and botanists from all over the world parts of Russia, Europe, Australia, Asia, Africa and South America among others. Around fifty species of the eucalyptus trees from Australia are to be found on the grounds, as well as species of pistacia, olive and pomegranate, all introduced from other areas. Succulents from Africa, evergreens from Japan and Italy, and cacti from Central and South America and the West Indies are also included in the introductions into the garden. Attracting many visitors from the time of its conception, this "garden in the desert" now brings in about 12,000 registered visitors annually, many of whom report the pleasure they derive from observing the plant and animal life of the area. Other visitors, botanists, and biologists, making studies of plant and animal life, come in for information and assistance in their studies. Thailand, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Belgium, India, Italy, Turkey, Germany, Switzerland and Great Britain are only a few of the homes of visitors. Ayer Lake, with its hundreds of fish, is an attraction for old and young alike. The lake, named after Judge Charles Ayer, Colonel Thompson's "right hand man," is the reservoir providing irrigation water to the garden. Picket Post House, sold to a private party in 1946 by the Arboretum Board, makes an impressive picture on the cliffs in the background above the trail, while Queen Creek, linedwith native cottonwood trees, flows part of the year below the canyon rim, with Picket Post Mountain a majestic backdrop for the overall picture. At the stone house on the canyon trail, originally a homesteader's home, and later furnished and further completed as a play house for his grandchildren, the Colonel arranged a setting of pomegranates, oranges, roses and numerous flowers that give it an air of quiet seclusion. In the cactus garden such plants as the Boojum tree, from Baja California a tree that must be seen to be believed mingle with the native chollas, prickly pears, hedgehogs, fishhook, compass and golden barrels, and other plants such as catsclaw, mesquite and creosote bush. The agave, or century plant, a member of the Amaryllis family, is wellrepresented with several species scattered through the garden. Yuccas, from the Spanish Bayonet to the Lord's Candle, send up their lofty plumes of flowers yearly, while the wild lupines, pentstemon, Mexican goldpoppies and California poppies put out colorful blooms in season.

with native cottonwood trees, flows part of the year below the canyon rim, with Picket Post Mountain a majestic backdrop for the overall picture. At the stone house on the canyon trail, originally a homesteader's home, and later furnished and further completed as a play house for his grandchildren, the Colonel arranged a setting of pomegranates, oranges, roses and numerous flowers that give it an air of quiet seclusion. In the cactus garden such plants as the Boojum tree, from Baja California a tree that must be seen to be believed mingle with the native chollas, prickly pears, hedgehogs, fishhook, compass and golden barrels, and other plants such as catsclaw, mesquite and creosote bush. The agave, or century plant, a member of the Amaryllis family, is wellrepresented with several species scattered through the garden. Yuccas, from the Spanish Bayonet to the Lord's Candle, send up their lofty plumes of flowers yearly, while the wild lupines, pentstemon, Mexican goldpoppies and California poppies put out colorful blooms in season.

The Arboretum is a true sanctuary for birds of numerous species, resident and transient. Among the resident species are Gambel's Quail, Cactus Wrens, Cardinals, Curve-billed Thrashers, as well as several sparrows and woodpeckers. The Phainopepla, Towhee, Oriole, and Hummingbird are numbered among the visitors, as are some of the Warblers and Swallows. Although no animals are in captivity for viewing at the Arboretum, there are many rabbits, squirrels, and reptiles and amphibians to be seen occasionally in the area. The administration building, constructed of rough native rock in 1926, houses the library, offices, laboratories, fireproof vault, supply room and lobby. Greenhouses adjoin the lobby on either side, with the west wing being devoted to succulent plants from Africa, and the east one housing cacti from warmer climates. Open to the public daily from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., with no charge for admission, the Arboretum offers beauty beyond mere words to visitors, many of whom are drawn back year after year. A receptionist is available in the lobby of the administration building between the hours of 9:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m., and will furnish visitors with tour information and answers to questions in general. The gardener at the Arboretum is Nat Patterson, an 83-year-old Apache Indian from the San Carlos Indian Reservation who was employed by Colonel Thompson in 1926 to work on the grounds. In the forty years since, Nat has continued as gardener, irrigator, and general clean up man. Living in an adobe house he built on the Arboretum grounds in the early years of the garden's existence, Nat has raised his family there. A son and other family members are still with him. Often overlooked, seldom noticed, Nat is yet a truly historical part of the Arboretum. When he cares to talk, which is seldom, he can give visitors an excellent history of the place.

By W. HUBERT EARLE, Director Desert Botanical Garden, Phoenix, Arizona An Intimate Study of Our Curious Cacti FAIR ARE THE

Out of Nature's vast storeroom of plants have come, during the past thousands of years, our curious cacti. They have evolved, according to botanical deductions, from the briars or clambering roses, and there are few missing links in the evolutionary chain.

No discoveries have as yet been made of fossilized cacti, either pollen or plants, and it seems reasonable to believe that the Cactaceae is one of the youngest of plant families.

It is surmised that earth movements in the West Indies tilted some islands, causing blockage of prevailing sea winds, with drying of the lakes and rivers. This condition created an arid ecological situation in which many plants slowly perished, but several survived by gradually changing their forms. One outstanding survivor was a briar that evolved into a plant bearing thickened leaves, bark with chlorophyll, and fleshy stems. This plant is known as Pereskia, the first Cactus.

The plants flourished in the West Indies and bore many fruits which were relished by the birds. In their turn, the birds, flying south to the northern coast of South America, inadvertently transported the seeds of the Pereskia. These seeds germinated and the plants established themselves by adapting to different soils, climates and elevations.

Adaptation took a variety of forms. If the sun was intense, the plant would produce many spines to shade itself. If there were continuous winds, the plant would grow close to the ground, hugging it for self-preservation. If it were growing in a forest, it would grow upright, seeking the sun. If it were in grassland, it would grow up to about a foot tall and make offsets around its base. If it were growing in freezing areas, it would become prostrate, lie on the ground during the cold and rising again the following spring.

To survive, the plants developed heavy outer cuticle, coatings of wax to prevent entrance of the sun's heat rays. They formed outer ribs, flutes and nipples to allow for expansion and contraction of stored food and moisture. Some plants, like our "Arizona Queen of the Night," developed an underground tuber, weighing up to sixty pounds, for storage purposes.

The leaves of all trees and shrubs carry the chlorophyll for the plant, but in the case of the cacti, which were progressively losing their leaves, this process was gradually translocated to the pith under the cuticle of the plant's body.

The moisture that is stored in the plant for growth and survival in periods of drought would evaporate rapidly in the heat of our deserts if it were simply in the form of water, so the plant chemically changes all water coming into the plant through its roots into a sticky mucilaginous juice able to withstand low humidity and high temperatures. continued

FLOWERS OF SPRING

Already a member? Login ».