FAIR ARE THE FLOWERS OF SPRING

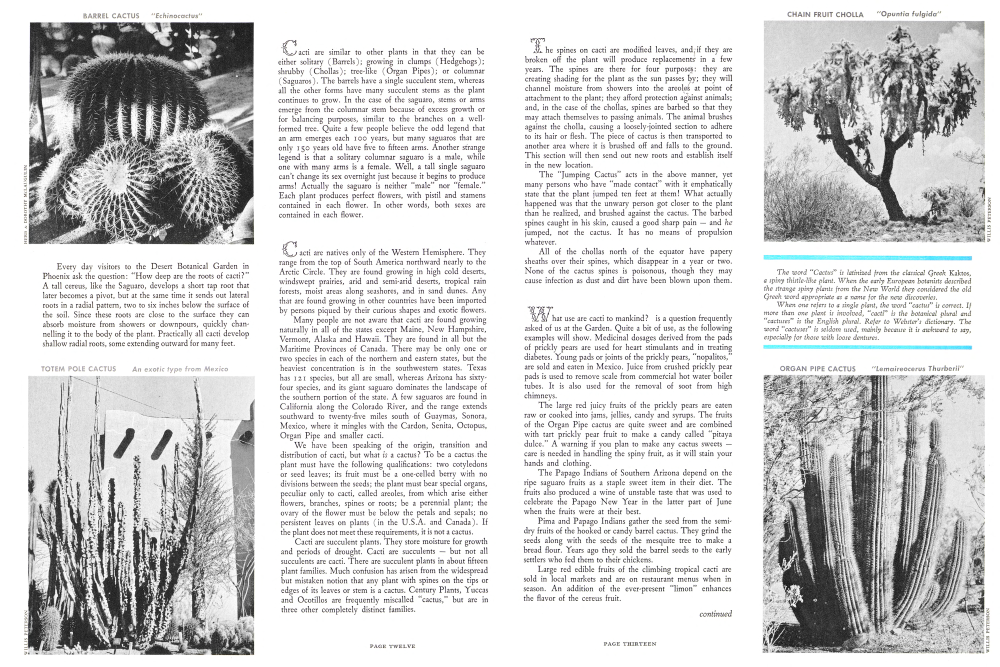

BARREL CACTUS "Echinocactus"

Cacti are similar to other plants in that they can be either solitary (Barrels); growing in clumps (Hedgehogs); shrubby (Chollas); tree-like (Organ Pipes); or columnar (Saguaros). The barrels have a single succulent stem, whereas all the other forms have many succulent stems as the plant continues to grow. In the case of the saguaro, stems or arms emerge from the columnar stem because of excess growth or for balancing purposes, similar to the branches on a wellformed tree. Quite a few people believe the odd legend that an arm emerges each 100 years, but many saguaros that are only 150 years old have five to fifteen arms. Another strange legend is that a solitary columnar saguaro is a male, while one with many arms is a female. Well, a tall single saguaro can't change its sex overnight just because it begins to produce arms! Actually the saguaro is neither "male" nor "female." Each plant produces perfect flowers, with pistil and stamens contained in each flower. In other words, both sexes are contained in each flower.

Every day visitors to the Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix ask the question: "How deep are the roots of cacti?" A tall cereus, like the Saguaro, develops a short tap root that later becomes a pivot, but at the same time it sends out lateral roots in a radial pattern, two to six inches below the surface of the soil. Since these roots are close to the surface they can absorb moisture from showers or downpours, quickly channelling it to the body of the plant. Practically all cacti develop shallow radial roots, some extending outward for many feet.

TOTEM POLE CACTUS An exotic type from Mexico

Cacti are natives only of the Western Hemisphere. They range from the top of South America northward nearly to the Arctic Circle. They are found growing in high cold deserts, windswept prairies, arid and semi-arid deserts, tropical rain forests, moist areas along seashores, and in sand dunes. Any that are found growing in other countries have been imported by persons piqued by their curious shapes and exotic flowers. Many people are not aware that cacti are found growing naturally in all of the states except Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Alaska and Hawaii. They are found in all but the Maritime Provinces of Canada. There may be only one or two species in each of the northern and eastern states, but the heaviest concentration is in the southwestern states. Texas has 121 species, but all are small, whereas Arizona has sixtyfour species, and its giant saguaro dominates the landscape of the southern portion of the state. A few saguaros are found in California along the Colorado River, and the range extends southward to twenty-five miles south of Guaymas, Sonora, Mexico, where it mingles with the Cardon, Senita, Octopus, Organ Pipe and smaller cacti. We have been speaking of the origin, transition and distribution of cacti, but what is a cactus? To be a cactus the plant must have the following qualifications: two cotyledons or seed leaves; its fruit must be a one-celled berry with no divisions between the seeds; the plant must bear special organs, peculiar only to cacti, called areoles, from which arise either flowers, branches, spines or roots; be a perennial plant; the ovary of the flower must be below the petals and sepals; no persistent leaves on plants (in the U.S.A. and Canada). If the plant does not meet these requirements, it is not a cactus. Cacti are succulent plants. They store moisture for growth and periods of drought. Cacti are succulents but not all succulents are cacti. There are succulent plants in about fifteen plant families. Much confusion has arisen from the widespread but mistaken notion that any plant with spines on the tips or edges of its leaves or stem is a cactus. Century Plants, Yuccas and Ocotillos are frequently miscalled "cactus," but are in three other completely distinct families.

CHAIN FRUIT CHOLLA "Opuntia fulgida"

The spines on cacti are modified leaves, and, if they are broken off the plant will produce replacements in a few years. The spines are there for four purposes: they are creating shading for the plant as the sun passes by; they will channel moisture from showers into the areoles at point of attachment to the plant; they afford protection against animals; and, in the case of the chollas, spines are barbed so that they may attach themselves to passing animals. The animal brushes against the cholla, causing a loosely-jointed section to adhere to its hair or flesh. The piece of cactus is then transported to another area where it is brushed off and falls to the ground. This section will then send out new roots and establish itself in the new location.

The "Jumping Cactus" acts in the above manner, yet many persons who have "made contact" with it emphatically state that the plant jumped ten feet at them! What actually happened was that the unwary person got closer to the plant than he realized, and brushed against the cactus. The barbed spines caught in his skin, caused a good sharp pain and he jumped, not the cactus. It has no means of propulsion whatever.

All of the chollas north of the equator have papery sheaths over their spines, which disappear in a year or two. None of the cactus spines is poisonous, though they may cause infection as dust and dirt have been blown upon them.

What use are cacti to mankind? is a question frequently asked of us at the Garden. Quite a bit of use, as the following examples will show. Medicinal dosages derived from the pads of prickly pears are used for heart stimulants and in treating diabetes. Young pads or joints of the prickly pears, "nopalitos," are sold and eaten in Mexico. Juice from crushed prickly pear pads is used to remove scale from commercial hot water boiler tubes. It is also used for the removal of soot from high chimneys.

The large red juicy fruits of the prickly pears are eaten raw or cooked into jams, jellies, candy and syrups. The fruits of the Organ Pipe cactus are quite sweet and are combined with tart prickly pear fruit to make a candy called "pitaya dulce." A warning if you plan to make any cactus sweets care is needed in handling the spiny fruit, as it will stain your hands and clothing.

The Papago Indians of Southern Arizona depend on the ripe saguaro fruits as a staple sweet item in their diet. The fruits also produced a wine of unstable taste that was used to celebrate the Papago New Year in the latter part of June when the fruits were at their best.

Pima and Papago Indians gather the seed from the semidry fruits of the hooked or candy barrel cactus. They grind the seeds along with the seeds of the mesquite tree to make a bread flour. Years ago they sold the barrel seeds to the early settlers who fed them to their chickens.

Large red edible fruits of the climbing tropical cacti are sold in local markets and are on restaurant menus when in season. An addition of the ever-present "limon" enhances the flavor of the cereus fruit.

The word "Cactus" is latinized from the classical Greek Kaktos, a spiny thistle-like plant. When the early European botanists described the strange spiny plants from the New World they considered the old Greek word appropriate as a name for the new discoveries.

When one refers to a single plant, the word "cactus" is correct. If more than one plant is involved, "cacti" is the botanical plural and "cactuses" is the English plural. Refer to Webster's dictionary. The word "cactuses" is seldom used, mainly because it is awkward to say, especially for those with loose dentures.

ORGAN PIPE CACTUS "Lemaireocerus Thurberii"

"Blossoms of the Cholla Cactus"

The small pincushion cacti produce red chili-shaped fruits locally called “chillitos” that are relished by the Indians because of their tart strawberry-like taste. It should be pointed out that all cacti fruit are edible, but not all of them are palatable. The fruits of the desert prickly pears are a good source of moisture and food for desert survival. We warn desert travellers not to gorge themselves on this unfamiliar food, as it might upset their stomachs.

Cattle and other browsing animals have survived long periods of drought by eating prickly pear pads and the spiny joints of the chollas. Animals will not grow fat on this diet, but will live until better forage is available. Many ranchers in drought-ridden areas of the Southwest burn the spines off the prickly pear plants so that their cattle can easily eat the pads and stems.

The dead trunks and branches of chollas make short, hot campfires. The long, dried-out rods from a dead saguaro or other tall cereus have been used for many years by the Indians in the construction of their small desert homes. Mud is plastered on and between the rods to make the walls and roof weatherproof. The skeletons of chollas are prized by many persons who wish to make novelties out of this unusual wood, which is also used in floral arrangements and dish gardens. Care should be taken in picking up any of this “desert driftwood” as the hollow branches can harbor scorpions, centipedes, small snakes, etc., that will at least give a fright to the newcomer in the desert.

Flowers of the cacti are unsurpassed in form, color, brilliance, variety of color, by any other plant family, including even the orchids. Flowers vary in size from the pink “match head” of the Button Cactus to the fifteen-inch wide nightflowering Moon Cereus. All cacti flowers have the basic rotate arrangement of petals gement of petals found in the roses, and are borne on an inferior ovary which when pollinated becomes the fruit.

Impatient visitors to our desert ask, “When will all the cacti be in bloom?” Contrary to general belief, the different species of cacti will not all bloom at the same time in the same area. The purpose of this is that, in flowering at different times, the flower will not become cross-pollinated, and thus the plants will not lose their present characteristics.

In the sun's hot rays our desert cactus flowers will remain open for just one day. Sometimes as a cloud passes in front of the sun a prolonged shadow will cause cactus flowers to close. If this happens, they will not reopen. Colorful day-flowering cacti are quickly receptive to pollination by bees, birds and ants. White night-flowering cacti are pollinated by moths, birds, bats and ants. Flowers on cacti at high elevations will remain open for three to five days, because of cooler weather.

Very few of the cacti have scented flowers. Our “Arizona Queen of the Night” is an exception, giving off in the night air an exotic odor, rather like a heavy Easter lily scent, which can sometimes be detected a quarter of a mile downwind from the plant during the blossoming period in the latter part of June or sometimes into the middle of July.

Curious Cacti

As a four-year-old in his native Winnipeg, Canada, W. Hubert Earle had his first contact with cacti. He discovered them with his bare feet while picking wildflowers. In 1923 he moved to Bloomington, Indiana, completing high school and attending Indiana University. No cactus contacts in this period. But in 1940 he and his wife, Lois, with their two sons, moved to Gary, Indiana, and around their home in the sand dunes at the southern tip of Lake Michigan, he had his second contact with cacti, as prickly pears were plentiful on the dunes.

Barrel Cacti of many types are found throughout the state and supposedly are the traveller's water reservoir. We don't recommend depending on them. Barrels in the high elevations do have a palatable moisture that can be extracted by vigorous chewing of the pulp, but those in the low hot desert have an acrid taste that will do nothing but increase your thirst. Carry a canteen of water when on the desert. That is your most dependable reservoir.

Hedgehog Cacti of many forms range the entire state. The Rainbow Hedgehog found in Southern Arizona along the Mexican border has bands of different-colored spines. Its two-toned flower is a beauty. The Strawberry Hedgehog found in Central and Western Arizona produces spine-covered red fruit with a strawberry flavor during May.

The diminutive Fishhook Pincushions are a dainty delight with their crowns of small flowers during May, June and July. Many species found in Central and Southern Arizona are usually growing under bushes for protection from the summer sun.

Organ Pipe Cactus is found near and in the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, south of Ajo. This cereus flowers at night with flowers smaller than those of the Saguaro. The arms of the plant arise as do the pipes of an organ, hence the name.

Senita is another cereus, about as large as the Organ Pipe, bearing small pink flowers followed by smooth round red fruits the size of marbles. It has gray bristly spines along the edges of its ribs near the apex of the plant, giving it an aged appearance.

Prickly Pears abound throughout the entire state. Their yellow-to-red flowers are an attractive addition to the desert floor during the spring months.

This might have been all, and he might have remained an insurance man with a stronger than average interest in plants, but for a serious health problem that developed in 1944. He developed asthma, and doctors told him to move to a drier climate or live for about three months. Thus, in September, 1945, he arrived in Arizona and found relief in the desert at Cactus, Arizona. After resting for a year and a half, he began work at the Desert Botanical Garden with no knowledge of desert plants, but under the skillful tutelage of W. Taylor Marshall, Director. He became Superintendent in 1951 and on Mr. Marshall's death in 1957 became Director. He has continued and expanded the Garden's public lecture program, the building programs, and other programs to make the Garden a vital member of the community.

He is editor of the monthly SAGUAROLAND BULLETIN, and has written Cacti of the Southwest, now in its second printing. He is also the author of Cacti, Wildflowers and Desert Plants in Arizona, published by the Arizona Development Board, and has edited The Southwestern Desert in Bloom. In addition, his articles have been published here and abroad.

He is a lecturer in high schools for the National Academy of Science, through the Arizona Academy of Science. Lecturing at the Garden and elsewhere in this country has occupied much of his time, and a few years ago he was invited to dedicate a new Botanical Garden in Japan, where he also gave a series of lectures.

He has visited Botanical Gardens in Hawaii, Singapore, Hongkong, Manila, and many cities in the U.S.A., giving assistance to the growing of desert plants. He has travelled extensively through Mexico, collecting seeds and plants for the Garden, and photographing plants.

He was elected a Fellow, 1964, of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and a Fellow, 1965, of the Cactus and Succulent Society of America. He is also a professional photographer.

The Beavertail Prickly Pear grows in Western Arizona along the Colorado River drainage. Its beaver-tail-shaped pads conceal short barbed hairs that could readily be used for an itching powder. The plant flowers profusely in March with brilliant cerise blossoms.

The Chollas, which are cylindrical Prickly Pears, cover the state either as solitary plants or in large colonies. The Teddybear Cholla, at a distance, gives the appearance of a large flock of sheep grazing on hillsides. Beware of these plants, for their barbed spines are painful. Care should be taken in removing a joint that has attached itself to you, so that the pulled-off joint is not directed at your face or eyes. A sharp jerk could be dangerous. Unwise dogs, attempting to dislodge the cholla joints from their bodies, sometimes have their tongues and mouths pierced with spines that will have to be removed by a veterinarian.

Arizona abounds in spectacular cacti in its deserts and hills, and they should be seen in the spring to be appreciated, photographed, painted or studied. Do not collect these plants. The State Plant Laws prohibit the removal of all plants from State, Federal, Indian Reservation, National Monument and Parks lands. Fines up to three hundred dollars can be levied against violators of this law. We want these plants to remain on the lands for the benefit of future generations. Wanton removal could lead to complete destruction of certain species.

All of the Arizona species are set aside in a special section for visitors at the Desert Botanical Garden, 6400 East McDowell Road, Phoenix, which is open daily, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. There are illustrated lectures Thursday and Sunday at 3 and 4 p.m., and classes on Wednesday at 3 p.m. from November through April for those persons wishing to become familiar with the identification or the growing of desert plants....

THE AUTHOR

In a natural showplace near Tucson, Arizona, the wonder-world of the desert and its environs is displayed alive at the unique and fascinatingTo a “first visit” guest there are still just two “main” buildings, for as the porch ramada which separates them is approached a breath-taking vista stretches ahead, terminating sixty miles away on two tiny peaks that are in Mexico. Prominent on the horizon is Baboquivari, sacred mountain of the Papagos the peoples that once controlled this area. And to the right of Baboquivari is the 6,875 ft. summit of Kitt Peak, home of the world's newest and largest solar telescope. But a shoulder of the distant mountain manages to hide these instruments that probe the sky, just as careful planning, building and blending makes unobtrusive the many wonders of the Desert Museum as a person traverses its mile of trails through beautiful desert country.

arizona sonora DESERT MUSEUM

In October of 1951 the Pima County Park Commission passed a resolution: “To establish Tucson Mountain Park and the buildings known collectively as ‘The Mountain House’ as a leading educational center for the purpose of acquainting the public with their rich but vanishing heritage in wildlife, plant life and scenic values to the end that, through knowledge, will come appreciation and a better attitude toward all resource conservation.” That, in short, was the start of the present Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum a few buildings built with federal funds during the depression of the mid-thirties, a picturesque road winding fifteen miles west of Tucson with one of the finest cactus forests in the United States, and the determination of two men, William H. Carr and Arthur N. Pack, to achieve an institution of learning wherein education would become a pleasurable avocation. Now, fifteen years later, their dreams have come true, for this combination museum, zoo, and botanical garden, known as a living museum, draws 229,000 people a year; and although most of them spend a couple of hours, many spend a day, and more than just a few return on the morrow.

As a starter let's head west toward a sky that is aglow from a sinking sun. A sign over a small door on an adobe colored building mentions vampire bats, the only creatures in the world which soon after infancy subsist entirely on blood. As the darkened enclosure is entered a tiny red button calls attention to a Colt 45 which swivels through a safety glass window. When the trigger is pressed a beam of light protrudes from the barrel and with simple wrist action can be used to locate a cluster of these strange animals hanging up-side-down asleep in a cavern crevice.

These vampires, one of only two captive groups on display in the United States, just barely enter the southern boundary of Sonora, Mexico, which makes them a legitimate display for the Desert Museum, for the institution makes no attempt to compete with the world's larger museums or zoos but instead specializes in the flora and fauna of Arizona and its neighboring states to the south Sonora and Baja California. On the walls of the vampire room there are two highly enlarged bat skulls, one of an insecteating variety and the other of the museum's blood drinkers. The latter shows the highly specialized teeth, razor sharp, which are used by the creatures to painlessly slice a slot in the hide of a sleeping mammal. Across the room another museum type display depicts a bat in pursuit of prey. The moth being chased, however, is not trailed by eyesight but by echo location wherein staccato vocal noises of the pursuer are bounced back to supersensitive ears and instantly translated to tell distance, direction, and size. So in this room there are informative exhibits, both living and dead, which give a partial reason for the organization's name being “museum” instead of “zoo.” Just outside the door a vine-covered shade ramada covers a low-walled enclosure which emphasizes the museum's aim for audience participation. A sign near the wall reads “You are welcome to handle these tortoises gently.” That last pleading word has been heeded despite the fact that at times the enclosure has more children than turtles. This compassion for animals, plants and the other displays is in marked contrast to the vandalism suffered by many institutions of similar nature. Possibly it's the distance from town which weeds out the idle or uninterested. Maybe it's the text on the thought provoking labels which makes the wonders of nature too interesting to destroy. Even occupied nests of wild birds within arm's reach of the busy trails successfully raise young despite prominent signs which call attention to, and describe the tenants. Briefly the attitude so often expensively encountered in a city institution, wherein a mother implies: "Johnny, go in and destroy labels for an hour; I have some shopping to do" does not occur at the Desert Museum.

NATURAL HABITAT CONDITIONS AND PERTINENT INFORMATION PLAQUES MAKE A "LIVING TEXTBOOK"

Around the corner from the walk-in tortoise enclosure there is a spacious area devoted to black bears, largest mammals to be displayed at the Desert Museum. The combined weight of the two would now be close to 800 pounds but, when acquired a few years after the museum opened its doors to the public, each could be held in the hand if the holder had a complete disregard for his extremities. Early in their lives the mother had been shot and they, as orphans, had been sold to a bartender in Northern Arizona as an outdoor "ad" for his place of business. As with most roadside zoos that try to keep animals as curiosities there were complaints and when they reached the Arizona Game and Fish Commissioners the cubs were confiscated and given to the Desert Museum. This association with the Game Department has been mutually beneficial to both organizations, for in a state as diversified as Arizona the animals of the various areas and life zones are many. Orphans and cripples are discovered all over the state, and ringing phones of both organizations are constantly reporting such finds. In the Tucson area the Desert Museum has become the repository, the infirmary where many have been brought back to varying degrees of health. Some, of course, never recover sufficiently to be liberated and on many occasions those tediously cared for and finally loosed to the wild return to the cages where they were patients, and try to get back in.

Some destruction of wildlife is unavoidable. Creatures are hit by cars, crash into fences, and birds try to fly through plate glass windows. Such casualties will always result from human occupation of the land. However, there is a small segment of the human population that completely disregards the teachings of the various conservation organizations throughout the state. They consider anything that moves as a target. Audubon's societies, Rod and Gun clubs, and the museum's "Desert Ark" a station wagon which carries animals to tens of thousands of school children each year, are all actively fighting this type of senseless "sport" which takes a great toll of wildlife.

With the thought that visual examples might cut this waste, a prominent sign was recently placed on the bath near the extensive bird display at the Desert Museum. It reads: "The great majority of the birds within the enclosures that you are approaching were obtained as orphans, then hand-raised to maturity. These have never known any other life and can not successfully be liberated and expected to survive without human help.

"Some within the cages were injured either by cars, fences, electric wires, or even guns in the hands of thoughtless people. These have been nursed back to health and during the tedious process have become semi-tame.

Already a member? Login ».