ARIZONA-SONORA DESERT MUSEUM

"The Museum receives about 20 phone calls per day regarding the care of crippled birds. The num ber of calls almost doubles immediately after Christmas - and remains high until the novelty of gift .22 rifles and BB guns subsides."

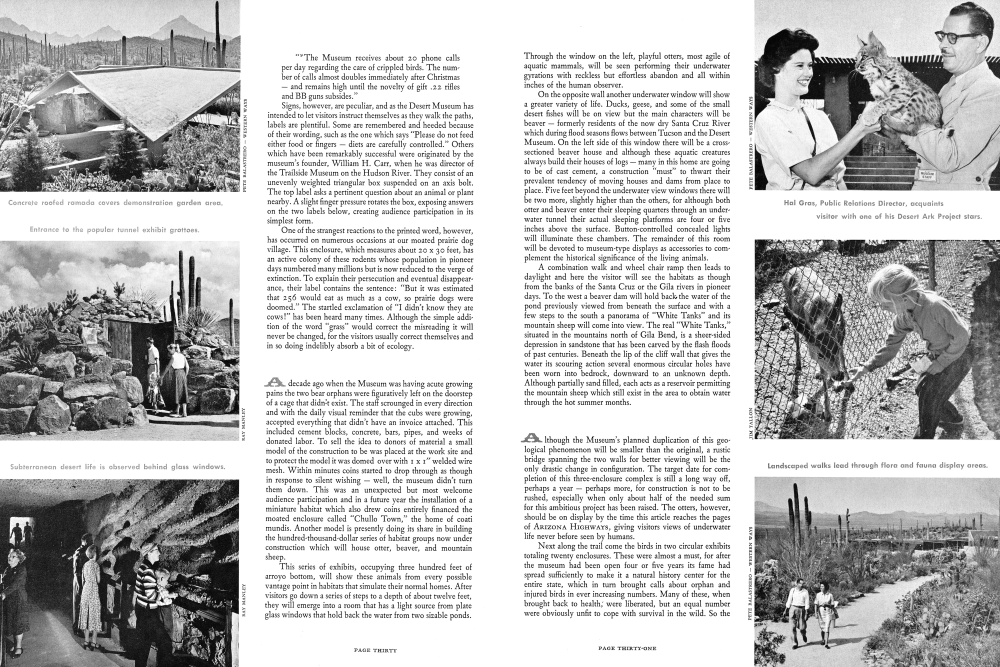

Signs, however, are peculiar, and as the Desert Museum has intended to let visitors instruct themselves as they walk the paths, labels are plentiful. Some are remembered and heeded because of their wording, such as the one which says "Please do not feed either food or fingers - diets are carefully controlled." Others which have been remarkably successful were originated by the museum's founder, William H. Carr, when he was director of the Trailside Museum on the Hudson River. They consist of an unevenly weighted triangular box suspended on an axis bolt. The top label asks a pertinent question about an animal or plant nearby. A slight finger pressure rotates the box, exposing answers on the two labels below, creating audience participation in its simplest form.

One of the strangest reactions to the printed word, however, has occurred on numerous occasions at our moated prairie dog village. This enclosure, which measures about 20 x 30 feet, has an active colony of these rodents whose population in pioneer days numbered many millions but is now reduced to the verge of extinction. To explain their persecution and eventual disappear ance, their label contains the sentence: "But it was estimated that 256 would eat as much as a cow, so prairie dogs were doomed." The startled exclamation of "I didn't know they ate cows!" has been heard many times. Although the simple addi tion of the word "grass" would correct the misreading it will never be changed, for the visitors usually correct themselves and in so doing indelibly absorb a bit of ecology.

A decade ago when the Museum was having acute growing pains the two bear orphans were figuratively left on the doorstep of a cage that didn't exist. The staff scrounged in every direction and with the daily visual reminder that the cubs were growing, accepted everything that didn't have an invoice attached. This included cement blocks, concrete, bars, pipes, and weeks of donated labor. To sell the idea to donors of material a small model of the construction to be was placed at the work site and to protect the model it was domed over with 1 x 1" welded wire mesh. Within minutes coins started to drop through as though in response to silent wishing well, the museum didn't turn them down. This was an unexpected but most welcome audience participation and in a future year the installation of a miniature habitat which also drew coins entirely financed the moated enclosure called "Chullo Town," the home of coati mundis. Another model is presently doing its share in building the hundred-thousand-dollar series of habitat groups now under construction which will house otter, beaver, and mountain sheep.

This series of exhibits, occupying three hundred feet of arroyo bottom, will show these animals from every possible vantage point in habitats that simulate their normal homes. After visitors go down a series of steps to a depth of about twelve feet, they will emerge into a room that has a light source from plate glass windows that hold back the water from two sizable ponds.Through the window on the left, playful otters, most agile of aquatic mammals, will be seen performing their underwater gyrations with reckless but effortless abandon and all within inches of the human observer.

On the opposite wall another underwater window will show a greater variety of life. Ducks, geese, and some of the small desert fishes will be on view but the main characters will be beaver formerly residents of the now dry Santa Cruz River which during flood seasons flows between Tucson and the Desert Museum. On the left side of this window there will be a crosssectioned beaver house and although these aquatic creatures always build their houses of logs many in this home are going to be of cast cement, a construction "must" to thwart their prevalent tendency of moving houses and dams from place to place. Five feet beyond the underwater view windows there will be two more, slightly higher than the others, for although both otter and beaver enter their sleeping quarters through an underwater tunnel their actual sleeping platforms are four or five inches above the surface. Button-controlled concealed lights will illuminate these chambers. The remainder of this room will be devoted to museum-type displays as accessories to complement the historical significance of the living animals.

A combination walk and wheel chair ramp then leads to daylight and here the visitor will see the habitats as though from the banks of the Santa Cruz or the Gila rivers in pioneer days. To the west a beaver dam will hold back the water of the pond previously viewed from beneath the surface and with a few steps to the south a panorama of "White Tanks" and its mountain sheep will come into view. The real "White Tanks," situated in the mountains north of Gila Bend, is a sheer-sided depression in sandstone that has been carved by the flash floods of past centuries. Beneath the lip of the cliff wall that gives the water its scouring action several enormous circular holes have been worn into bedrock, downward to an unknown depth. Although partially sand filled, each acts as a reservoir permitting the mountain sheep which still exist in the area to obtain water through the hot summer months.

Although the Museum's planned duplication of this geological phenomenon will be smaller than the original, a rustic bridge spanning the two walls for better viewing will be the only drastic change in configuration. The target date for completion of this three-enclosure complex is still a long way off, perhaps a year perhaps more, for construction is not to be rushed, especially when only about half of the needed sum for this ambitious project has been raised. The otters, however, should be on display by the time this article reaches the pages of ARIZONA HIGHWAYS, giving visitors views of underwater life never before seen by humans.

Next along the trail come the birds in two circular exhibits totaling twenty enclosures. These were almost a must, for after the museum had been open four or five years its fame had spread sufficiently to make it a natural history center for the entire state, which in turn brought calls about orphan and injured birds in ever increasing numbers. Many of these, when brought back to health, were liberated, but an equal number were obviously unfit to cope with survival in the wild. So thebird cages came into being and the seventy-odd species now on display are truly multi-purpose. Captivity has meant the difference between life and death to many, as well as acquainting the public with the heritage of avian life which lives on the desert. Each specimen might be considered an ambassador, teaching a conservation message which may save the lives of others still in the wild, for the labels soon to be done in Spanish stress ecology or the inter-relationship of all life. Most zoos are justly proud when any wild animal in their care raises young in captivity, feeling that the function signifies that the animal is content with diet, treatment and surroundings. The Desert Museum has many such records and some are “firsts” for the entire world. The most outstanding of these occurred four or five years ago in the cage of burrowing owls when a pair started digging tunnels in the dirt floor. (This in itself was something of a record for in the wild they usurp the dens of small mammals and are supposedly devoid of digging skills.) Prior to this activity the owls would take dead mice from fingers with no sign of antagonism toward the hand that

Watershed Exposition displays show the story of water and soil conservation.

fed them. Almost overnight, however, attitudes changed. Hands were no longer tolerated but were attacked with a vengeance which made even brave keepers retreat. For several weeks only one of the pair remained visible, obviously on guard above a burrow where the mate was sitting on eggs. On the day that the young emerged to get their first view of daylight the valiant pair even tried to attack visitors outside the wire mesh and it was months before the pair settled down after setting a new and envious record for the United States. Other noteworthy births include a yearly litter of pups from the rare Mexican wolves. The progeny from this pair, at one time considered to be the only ones in captivity, have now stocked many zoos, so in spite of their predicted imminent extinction in the wild captive breeding may save the species. Even kit fox, smallest members of the family which live on sandy deserts, have raised young with the added distinction of having their yearly litter twelve feet underground in full view of the public. Their tunnel home is a new concept in museum-zoo dis-play, necessitated by the fact that although the desert abounds in animal life most of its creatures are nocturnal, escaping daylight heat by going underground where, under ordinary circumstances, they can't be seen. The tunnel exposition was built to show this diurnal phase of their lives. As daylight fades away behind a visitor going down the tunnel ramp, a dark underground world looms ahead. Cleverly executed rock walls have dens at eye level where sleeping mammals may be viewed through an almost unseen plate glass. With the concealed lighting it almost seems that a hand could touch the rattlers and other animals, or vice versa that they could reach out and touch you. Authenticity and faithful reproduction of detail paid off when a visitor in all seriousness asked one of the staff: "How was it known that a stalactite cavern existed at this spot before the tunnel was excavated to intercept it?"

beauty & value in minerals. For the rockhounds delight.

After viewing more than a dozen exhibits in the tunnel, a ramp leads one to the surface again and to a shade ramada which overlooks a stylized desert garden, envied by many desert estate owners. Originally planned by the Desert Museum andSunset Magazine as a cooperative project, it has a two-fold purpose: to show the use of native desert plants as ornamentals, and secondly if natives are used to conserve water by their use, for water on the desert is always in short supply.

Papago Indian exhibit contains many original artifacts.

Next along the trail comes "Water Street," a long line of exhibits which graphically stresses other phases of water conservation by means of speaker tapes, labels, and animated exhibits. The drip tower, for instance, has three plots of ground planted with varying densities of grass. From high above, droplets hit the dirt. Where the plant growth is dense, rich top soil still exists despite years of simulated rainfall but where it is sparse the loam has been carried away just as it is as a result of overgrazing. Instruments line the path, each telling a story about water. Some center the attention on evaporation and means for slowing it, others on capillary action or on the transpiration of moisture from plants. That the story is well told and pertinent to the times is evidenced by the interest of out-of-state colleges and universities that bus their students to the Desert Museum as part of their conservation courses and natural history.

From “Water Street” we walk along a few hundred feet of trails facing a fading but beautiful sunset, completing the ten acre self-guided tour where desert knowledge is available every few yards; and then come the buildings earlier by-passed for the trip through the grounds. An incongruous sign “Fishes and Amphibians” is above a door to the right, “incongruous” because neither is expected to be native to desert areas that have sometimes been described as “seas of sand.” But fishes there are on the desert. At least thirty-two were native at one time but the lowering of the water table, pollution, and the introduction of exotics have cut their numbers in half. Those still available are displayed in seven large wall tanks. One other tank contains salt water where, for the past five years, gulf denizens have thrived. This habitat is to be to a certain extent experimental, a test of the practicality of a much larger gulf display at some future date.

That amphibians, toads and frogs, should be seasonally abundant on the desert comes as another surprise to most tourists. To show winter guests these creatures that miraculously appear in the summer rainy season, four large dioramas and a number of small terrariums line the walls of the amphibian room. The four dioramas are much more than just cases to hold an animal, for when they were constructed the best of museum techniques were employed incorporating painted backgrounds and realistic foregrounds to pinpoint the specialized habitat of the living creature displayed. And the water within is not only real but flowing, the plants not fakes but growing, and in this combination the toads within remain as contented as though still in the wild.

The success of these living dioramas which have been copied by many institutions was so great that others were installed in the reptile room across the porch. This room, looked upon now and remembered as it was on opening day fifteen years ago, exemplifies progress. For months prior to the first public look, a herpetologist, William H. Woodin, scoured the countryside each night and built cages during the daytime to house his catches. Although the feat of being ready on Labor Day, 1952, seemed impossible to the then small board of directors made up of public-spirited Tucson citizens, his show was presentable on opening day. This untiring interest, attention to detail, and obvious leadership qualities made him the natural choice of trustees and staff to succeed William H. Carr when he became director emeritus and moved to New Mexico to start the now thriving Ghost Ranch Museum.

To say that the Desert Museum fills a need in Arizona is superfluous. Under its two directors it has grown to the point of being copied all over the world. In its comparatively short life it has been visited by over three million people, visitations which combined with memberships have made it selfsupporting, capable of existence and growth without resorting to any direct tax assistance. To say that the Desert Museum warrants a visit is also superfluous, for nowhere in the world is the entrancing lore of the desert so ably presented, education so painlessly absorbed, and where your visit and membership will help support a unique and valuable institution.

where the IN CROWD is

ANOTHER SPRING

Simply another spring. Nothing in that To marvel about. Unfailing cosmic plan Always provides another spring for man And bird and blossom. Thing to wonder at Would be the season's failure to appear In its due place. Then would we raise a cry Of desperation! All our trust in the sky Would be lost in the overturning of our year.

Yet over and over lifts in us the same Astonishment at this expected spring. Surely the waking season never came Upon the earth with such sweet gifts to bring! And though we know we've had all this before, Each year we think this time there's something more.

DESERT IN BLOOM

Carpet Beyond purchase Loomed of petal and leaf On warp and woof of winter rains And sun.

DESERT TREASURE

This land is so forbidding, Bleak and severe, Blazing in the noonday, Ashen, sere, Shivering in starlight, Shelterless, bare Only sand and cactus Everywhere.

But here you will find solace, Silence, peace, Beauty bone-deep, And spirit's release Treasure past price In these sage-clad drifts, If you open your eyes And your heart to its gifts.

IN THE DESERT

Both sunrise and sunset are a blaze of glory! Each in its own way tells a most thrilling story Of the Master Mind who invented it all To fill souls with wonder and hold them in thrall. The wonderful colors the Desert displays Make gorgeously beautiful the nights and days; And over it all is the wonderful peace That settles upon one, and seems to increase Till the Heavens above one, down to the earth's sod, Proclaim the encompassing Presence of God!

Yours Sincerely MORE ABOUT SUNSET CRATER:

We have read with much interest the November, 1966, issue of your magazine and wish to compliment you on the use of the unique format in presenting the county by county story of Arizona. It is an excellent presentation.

In reading same it has been noted that there is one error in the information furnished on Sunset Crater National Monument on page nine in the statement that "The road is not maintained in the winter." The entrance road to Sunset Crater has been kept open during the winter for the last three years, but not so the connecting or "loop" road between the two areas. However, the hard surfacing of this connecting road was com pleted in June 1965 and all visitors use roads in and between Wupatki and Sunset Crater National Monuments will be open for travel during the entire year.

In addition, a new visitor center is now under construction at Sunset Crater and should be open to visitor use sometime in 1967, completion date governed by construction conditions encountered during the coming winter.

IT'S A SMALL WORLD:

My wife just received a letter from Pansy Hartman Noble, Albany, California, which started off like this: "Alma C. Imes my son gave me your address from a telephone book. I am interested in locating a cousin, Tennis E. Imes, who had a letter published in the February, 1966, ARIZONA HIGHWAYS magazine, the only address being Santa Monica, Calif. Would appreciate any information you can give me, etc...."

Some time ago I received mail from you enclosing a request from Thad Covington, Escondido, Calif., for my address. The amazing thing to me is that I had not seen the cousin for 78 years, and Mr. Covington for about 40 years.

We are very thankful to your organization for this very fine service.

CHRISTMAS SONGS:

We particularly liked your Christmas issue. Your use of quotations from Christ mas songs and hymns throughout the magazine was particularly effective. And, of course, the photographs were superior as usual.

OPPOSITE PAGE

"CLARET CUP CACTUS." R. C. & CLAIRE MEYER PROCTOR. The Claret Cup plants are native to Eastern Arizona and New Mexico. The flowers remain open three to four days, which is unusual because most cactus flowers are open only one day. 41/4x41/4 Speed Graphic camera; Ektachrome; f.32 at 1/2 sec.; Rodenstock-Trionar lens; April.

BACK COVER

"PRICKLY PEAR AND OCOTILLO COLORFUL DESERT DUO." DARWIN VAN CAMPEN. Photo taken northeast of Mesa just outside the southern boundary of Usery Mountain Regional Park. In the foreground is a prickly pear cactus in bloom, one of the most common of all cacti found in Arizona. In the background, long limbs carrying garlands of purple flowers, is the ocotillo (pronounced "oh-co-teé-yo), one of the most beautiful of desert plants. 4x5 Linhof camera; Ektachrome; f.29 at 1/25th sec.; 150mm Symmar lens; April; bright sunlight; Weston Meter 400; ASA rating 50.

Already a member? Login ».