Where Copper is King

Of county illuminates the history and raison d'etre of Arizona more eloquently than Greenlee. Here is the state's largest copper mine second largest open pit on this continent in the foothills of some of Arizona's most beautiful scenic mountains. Below, in the fertile Duncan Valley, are thousands of acres of rich farmland. On every side, in valley and mountains, sleek beef cattle graze, and on every hand are reminders of a history more replete with hair-raising events than the most vivid TV imagination could invent.

Some 425 years ago the land that now is Greenlee County was seen for the first time by Europeans. Fray Marcos de Niza, preceded by his scout, the giant Moorish Negro slave Estevan, traversed the area to gather advance information which might lead a Spanish army to the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola. Estevan (sometimes called Estevanito or Little Steven) is said to have blazed a trail up the Gila to its junction with the San Francisco, thence up the latter into the White Mountains, which are the spine of Greenlee County, and ultimately to the Zuñi village of Hawikuh in what is now the northwest corner of New Mexico. At Hawikuh, Estevan and most of his colorful retinue of Indian slaves and retainers were killed when they ignored the Zuñis' demands to leave. The few who escaped the massacre met Fray Marcos on the trail, and that prudent prelate ventured only far enough to catch sight of the Zuñi village from a distance. Perhaps they were bathed in the long, golden light of a southwestern evening; but, in any event, Fray Marcos decided they might, indeed, be Cibola. He planted the flag of Spain and returned to Mexico City to make a report.

There his report coupled with the Spaniards' cupidity and remarkable credulity crystalized Viceroy Mendoza's resolution to win undying fortune and honor by capturing the legendary cities whose streets supposedly were paved with gold and silver and whose buildings were made of precious and semiprecious stones. In 1539 he commissioned Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, his own fair-haired boy and son-in-law of the treasurer of New Spain, to lead the army of conquest. Poor Coronado! One of the great ironies of all history is that he trudged over and near the richest bonanza of metallic mineral wealth the world has ever produced and never even suspected it. Had the King of Spain acquired even a tenth of the metallic wealth Arizona has since produced, the whole course of world history would have been changed. Spain could have mounted enough armies and launched enough navies to have fulfilled her wildest dreams of conquest. As it was, Coronado spent two and a half futile years in the field, finally to return to Mexico and disgrace. How different would have been his fate had he been able to recognize the potential of even that small part of the area he explored lying just north of the confluence of the Gila and San Francisco Rivers! If he could have taken back to Mexico City even the value of one modern year's metal production of Greenlee County he would have been a conquering hero. Greenlee's treasures remained hidden for another three centuries, however. Nor was it metallic treasure that white men first found there. Rather it was fur, principally beaver pelts. Accurate records are sparse detailing the wanderings of the rugged and inflexibly individualistic Mountain Men who were the United States' vanguard into the deep and dangerous wilderness of the intermountain West and Southwest. Contrary to popular impression today, such streams as the Gila, San Francisco, Blue and Black Rivers and Eagle and other creeks

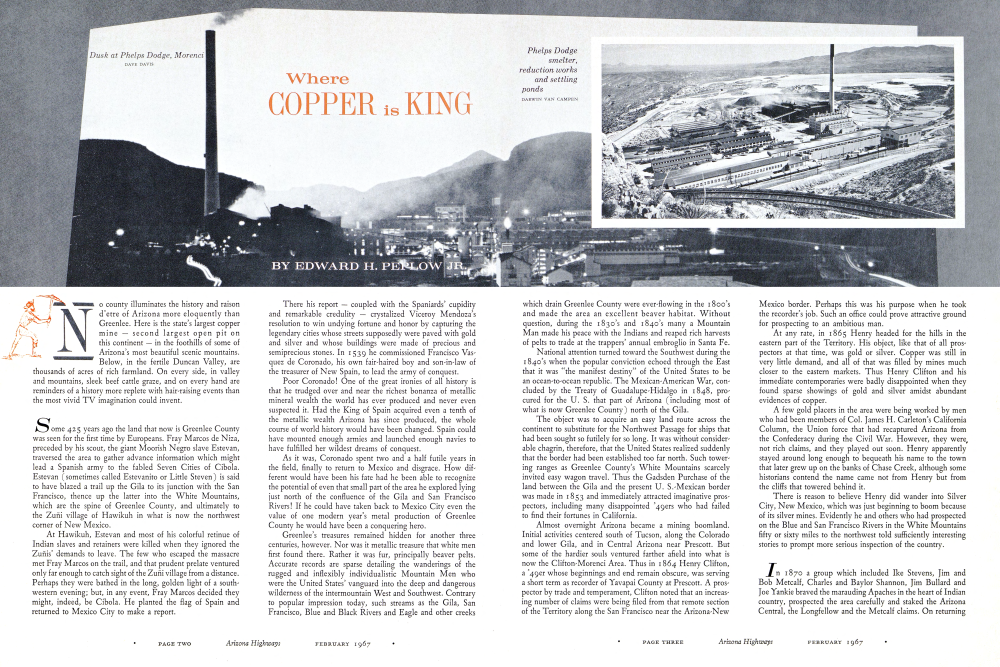

Phelps Dodge smelter, reduction works and settling ponds

which drain Greenlee County were ever-flowing in the 1800's and made the area an excellent beaver habitat. Without question, during the 1830's and 1840's many a Mountain Man made his peace with the Indians and reaped rich harvests of pelts to trade at the trappers annual embroglio in Santa Fe.

National attention turned toward the Southwest during the 1840's when the popular conviction echoed through the East that it was "the manifest destiny" of the United States to be an ocean-to-ocean republic. The Mexican-American War, concluded by the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in 1848, procured for the U. S. that part of Arizona (including most of what is now Greenlee County) north of the Gila.

The object was to acquire an easy land route across the continent to substitute for the Northwest Passage for ships that had been sought so futilely for so long. It was without considerable chagrin, therefore, that the United States realized suddenly that the border had been established too far north. Such towering ranges as Greenlee County's White Mountains scarcely invited easy wagon travel. Thus the Gadsden Purchase of the land between the Gila and the present U. S.-Mexican border was made in 1853 and immediately attracted imaginative prospectors, including many disappointed '49ers who had failed to find their fortunes in California.

Almost overnight Arizona became a mining boomland. Initial activities centered south of Tucson, along the Colorado and lower Gila, and in Central Arizona near Prescott. But some of the hardier souls ventured farther afield into what is now the Clifton-Morenci Area. Thus in 1864 Henry Clifton, a '49er whose beginnings and end remain obscure, was serving a short term as recorder of Yavapai County at Prescott. A prospector by trade and temperament, Clifton noted that an increasing number of claims were being filed from that remote section of the Territory along the San Francisco near the Arizona-New Mexico border. Perhaps this was his purpose when he took the recorder's job. Such an office could prove attractive ground for prospecting to an ambitious man.

At any rate, in 1865 Henry headed for the hills in the eastern part of the Territory. His object, like that of all prospectors at that time, was gold or silver. Copper was still in very little demand, and all of that was filled by mines much closer to the eastern markets. Thus Henry Clifton and his immediate contemporaries were badly disappointed when they found sparse showings of gold and silver amidst abundant evidences of copper.

A few gold placers in the area were being worked by men who had been members of Col. James H. Carleton's California Column, the Union force that had recaptured Arizona from the Confederacy during the Civil War. However, they were, not rich claims, and they played out soon. Henry apparently stayed around long enough to bequeath his name to the town that later grew up on the banks of Chase Creek, although some historians contend the name came not from Henry but from the cliffs that towered behind it.

There is reason to believe Henry did wander into Silver City, New Mexico, which was just beginning to boom because of its silver mines. Evidently he and others who had prospected on the Blue and San Francisco Rivers in the White Mountains fifty or sixty miles to the northwest told sufficiently interesting stories to prompt more serious inspection of the country.

In 1870 a group which included Ike Stevens, Jim and Bob Metcalf, Charles and Baylor Shannon, Jim Bullard and Joe Yankie braved the marauding Apaches in the heart of Indian country, prospected the area carefully and staked the Arizona Central, the Longfellow and the Metcalf claims. On returning

Rugged and Remote

to Silver City, the Metcalfs showed a sack of ore samples to the manager of the Lesinsky store, a man named Goulding. Goulding, who knew nothing about copper, shipped the sack to Henry Lesinsky in Las Cruces. Lesinsky, whose wanderings had led him through many a mining camp, including the gold fields of Australis, didn't know much about copper either. But he was knowledgeable enough to recognize that the ore ran 20-40 percent, that copper was selling for twenty-five cents a pound, and that the market for copper was growing rapidly as new uses for electricity were being found every day.

Lesinsky made a trip into the area with Mercalf and a heavily armed party. They succeeded not only in inspecting the copper claims but also in avoiding ambushes by the Apaches. Acting on the convictions developed on this trip, Lesinsky bought out the Stevens interests and the Longfellow Mine and induced Captain E. B. Ward to buy out the Arizona Central, Copper Mountain, Montezuma and Yankie claims.

The headquarters camp at the confluence of the San Fran cisco and Chase Creek, five miles below the Longfellow Mine, was pretty well established by 1872, while the settlement near the Longfellow was established that same year as Joy's Camp, named for Captain Miles Joy, deputy mineral surveyor who was sent to the district to stake out the filings.

Two years later William Church and his brother John arrived in Joy's Camp, and about the same time Captain Ward died. William Church proceeded to buy the four Ward claims from the Ward estate, then journeyed east to enlist capital. He succeeded in organizing the Detroit Copper Company, which was incorporated January 14, 1875. The name of the camp was changed to Morenci, after a town in Michigan.

Meanwhile the Lesiusky interests realized the profit poten tial of the Longfellow would be greatly enhanced if the ore could be smelted on the spot. They built a small stone furnace hard by the mine at the Stone House. The blast was supplied by a hand-operated bellows, and the ore, running better than 20 percent, was smeltered at the rate of two tons per day.

Predictably, this crude little furnace did not work very well, and Lesinsky soon replaced it with one near Clifton, where the blower could be driven by waterpower. At about the same time Detroit Copper built a small smelter at Clifton. then shortly moved it to Copper Mountsin.

James Colquhraun, who arrived on the Clifton-Morenci scene in 1883 and became one of the most significant men in the development of the district as well as in the history of the copper industry, wrote a warm, personalized history of the Clifton-Morenci district which was privately published in a limited edition. In it he commented on the early smelbers as follows: "In the slow smelting with charcoal in the stone fur paces, a considerable amount of iron was reduced. Part of this inon went into the copper bullion, which assayed 88 percent copper. Another part went into bottotus which gradually grew until they weighed three or four tons, when the furnace had to be torn down and a new one built. These bottoms were thrown into the slag dumps and gradually covered up, and there they remained until 1885, when I deg them up and converted them into good copper."

Frederick Remington Barr, writing in the Victory Resource Number of The Copper Era, April 12, 1943, said of the beginnings of the Clifton-Morenci mining industry, "The early years of exploration were fraught with hardships, disappointments and failures. The mines caved in, the Indians wrecked the ore trains (of wagons), the furnaces froze, and floods and fires from time to time cansed general havoc.

Picture Book Scenery

"All ore was mined by hand, trammed to the surface in wheelbarrows and hauled away from the mine by pack birros or in wagons. The reduction works consisted of crude little blast furnaces using charcoal for fuel and blast by hand or water power. The smelter product, pigs of black copper, was still 800 miles by bull team from the nearest railhead. However, the ore was rich, the men who worked it were accustomed to the hardships, and despite the high costs, the price of copper left a margin of profit.

"In time the steep burro trail to the mines was replaced by a wagon road, and tracks in the mines eliminated much wheel barrow tramming. The hand-blast adobe smelter in Chase Creek Canyon was replaced by the copper jacket furnace powered by water from the 'Frisco River. By 1880 the wagon road from the Longfellow mine to the smelter at the mouth of Chase Creek had been replaced by a railroad in the floor of the canyon connecting with a gravity incline to the mine.

"This twenty-inch gauge line was the first railroad in Ari zona and, although mules were the original motive power, the fall of 1880 marked the beginning of steam haulage. A tiny wood-burning locomotive, The Coronado, was purchased from K. K. Porter & Company and, after a long and circuitous route from Pittsburgh by rail and water around the southern tip of South America to San Francisco, thence to Yuma and overland to Clifton, was placed on the run from the works to the mine."

Commenting on the same railroad prior to the arrival of the little locomotive, Charles H. Dunning said in his book, Rock to Riches, "Mules rode the ore train down the hill, then hauled the empty cars back. The mules may have registered complaints about this constant uphill business, for in 1879 the Lesinskys brought in via an arduous overland trek a little loco motive from La Junta (Colorado). Some historians aver that this was the first locomotive in Arizona, while others accord that honor to another small engine hauled into the Clifton area via Yuma, after having been shipped around the Horn. The truth of the matter, however, seems to be that a Southern Pacific engine had crossed the bridge from California into Arizona at Yuma earlier 37 During the late 1870's the Morenci mines attracted con siderable national attention. Dunning quotes passages from a report written by A. Harnickell, a large dealer in copper, and published in Hinton's Handbook to Arizona, Says Dunning, "Just what Mr. Harnickell's interest was in writing such an ebulliently enthusiastic report is not clear. It was penned long before the founding of a chamber of commerce in the area. Had everything he said been literally true, it would have been unnecessary to work any other mine in the world for decades!"

By 1880, both the Lesinsky enterprise and the Detroit Copper Company were making good profits in spite of high costs and the many practical difficulties they encountered. Dunning says the price of copper was twenty cents a pound, the ore averaged 20 percent copper, a total of sixty to eighty tons a day was being produced, and that an informed guess would place the cost of copper, delivered, at about fourteen cents. Despite the sound growth and good health of their business, however, the Lesinsky interests began to be afraid that the market soon would be glutted with an oversupply of copper. The advent of transcontinental rail transportation (the Southern Pacific reached Tucson on March 17, 1880, the New Mexico border in September the same year) perhaps prompted them to fear that a great many new mines across the Southwest would open up and drive the price of copper away down.

Whatever their reasons, the Lesinsky interests in 1881 placed all of their mine holdings in the district on the market. A man in Kansas City, F. L. Underwood, was engaged to make the sale, which he accomplished when he sold both the Lesinsky and the Metcalf properties to a firm in Edinburgh, Scotland, which established the Arizona Copper Company Ltd.

According to Colquhoun, the capital of $4,000,000 was immediately subscribed. “The Board of Directors,” Colquhoun says, “promptly decided: to build a thirty-six inch gauge railroad from Lordsburg to Clifton; to erect a new smelting plant; to extend the Coronado railroad from Longfellow to Coronado; to build gravity inclines to connect the same with the Queen, Metcalf, and Coronado groups; to rebuild the Longfellow incline; to build the Longfellow railroad from the top of the Longfellow incline to the Detroit Mine, Morenci; and to equip the railroads, smelter and inclines with the necessary locomotives, cars, machinery, buildings, etc.

“Before the work was completed,” Colquhoun continues, “it was found that the cost would be at least twice as much as had been estimated, and this together with a cave-in in the Longfellow mine in November, 1882, shook the company to its foundation and even threatened its destruction The whole property was mortgaged for $1,800,000, all of which was required to complete the work in hand. The one mistake was in not raising enough capital in the first instance.” Colquhoun arrived in the district in 1883 as assayer, metallurgist and general assistant. He found the Arizona Copper Company's affairs in a depressed state and those of Detroit Copper only a little better. The difference was that William Church had not shared the Lesinsky fears of a glutted market but rather had foreseen a constantly expanding market which would require as much expansion as producers could manage.

Accordingly, Church had made a trip to New York in 1881. He had walked boldly into the offices of Phelps Dodge & Company and asked Daniel Willis James, a partner of William E. Dodge, Jr., for the loan of $50,000. His timing was perfect; Phelps Dodge needed a source of copper to supply their fabricating works at Ansonia, Connecticut. And the audacity of Church's approach intrigued James.

Phelps Dodge decided to check the Detroit holdings. They engaged Dr. James Douglas to go to Morenci and make a study. Dr. Douglas, who made many substantial contributions to the development of Arizona's copper industry, recommended Phelps Dodge make the loan and thus brought to the Greenlee County mining scene the first Phelps Dodge investment in what has proved to be a long continued and mutually profitable series of Greenlee investments in the area. The next few years were difficult for both companies. Colquhoun wrote, “We were all miserably poor in the early days... We had no money to invest in experimental plants; no engineering firms to design new plants for us; we had not even a surveyor Sometimes we worked without a boilermaker, and while this contributed greatly to the tranquility of the camp, it cost us much in other ways especially when our water jackets began to leak.

“It was during these trying periods when our daily bread depended on our daily output of copper, that a mighty flood swept down like an avalanche, destroying the dam which gave us power and water, and closing down our smelter. This was a staggering blow.” Faced with such overwhelming problems, the Colquhouns, the Churches and the rest of that hardy and courageous group carved for themselves places in the hierarchy of truly great, albeit largely unsung, heroes of western progress. If they had not won their battles, it is frightening to speculate how much our industrialization might have been delayed.

Perhaps the most difficult problem they faced and one that still is faced by the producers of vital copper across the country was the fact that the grade of ore available to them was constantly lowering. By 1885 the pockets of extremely rich ore the 20-40 percent variety had been mined out.

Colquhoun wrote, "In May, 1886, my friend William Church began to operate the first copper concentrating plant built in Arizona. He treated an oxidized ore running 6.5 percent (far too low for direct smelting) copper. The concentrates assayed 23.8 percent, and the tailings 3.92 percent."

It is interesting to note here that if the Morenci mine today found a body of ore as rich as those tailings of eighty years ago it would be considered a real bonanza!

But this, in essence, is the story of Arizona copper mining encompassed in the story of Greenlee County. It is the story of a constant battle of technology to convert yesterday's waste into today's and tomorrow's usable ore. When one looks at the tremendous open pit at Morenci and the huge plants in which the ore is concentrated and smelted, one is looking at monuments to the creative imaginations of the engineers who have worked virtual miracles.

Sparked by the success of Church's concentrator, Colquhoun himself designed and built a plant of his own twice the size of Detroit's. It worked well. Colquhoun said, "Indeed, if it had not been for this concentrator, the Arizona Copper Company would soon have come to its end."

Both companies bumped along for the next several years. Colquhoun notes that Detroit was forced to close down on several occasions, ". . . but the intrepid William Church never lost courage."

"However," Colquhoun wrote, "those hard and sterile years were not unfruitful. We were gaining in knowledge and experience, and were being prepared to tackle the greater problems which lay ahead."

In 1895 William Church decided to retire. He sold his interest in Detroit Copper Company to Phelps Dodge Corporation, which shortly thereafter became full owner of the property. Colquhoun, meanwhile, had pioneered one of the great breakthroughs of the industry when he built a leaching plant to treat low-grade, oxidized copper ores. Like his concentrator, it bailed the company out, but not until Colquhoun had been appointed manager of the company and had, in that capacity, had a head-on confrontation with the company that held the mortgage on the property. With candor and humor rare in such trying circumstances, he reports that he talked to the mortgage company and told them there was no immediate prospect of paying the accumulated interest. The only alternative the mortgagor had, Colquhoun reminded them, was to take over the Arizona Copper Company's property.

"It was then I pointed out to the mortgage company the Arizona Copper Co. was no more and no less than a white elephant. I was sure they did not want it. It was an expensive animal to feed," Colquhoun reported.

The mortgage company agreed to wait for the interest, and Colquhoun got his new plant built and once again scored a great success. But, as fast as one breakthrough was made, a new and more severe challenge arose. Now, in the mid-1890's, the high-grade ores were almost all gone, and even the reasonably high-grade oxides such as were treated successfully in the new leaching process were disappearing. All that seemed left was a new and very difficult type of ore.

It was a low-grade porphyry ore. By that is meant that fine grains of sulphides were disseminated in a fine-grained ground mass in low concentration. To recover the copper from this type of rock was a problem that had to be solved if the companies operating not only in Morenci but throughout Arizona were to survive long. History has shown that by far the largest quantities of Arizona copper were locked in such porphyry formations. Had Colquhoun and his crew and his contempo raries not been able to solve the problem and design a mill which succeeded in concentrating the sulphides in the porphyry formations, Arizona copper mining would have been set back incalculably.

But design it they did. Colquhoun, who was much more prone to self-deprecation than to bragging, understated the case when he said, "Thus was the first porphyry concentrator designed and brought to success, and this success meant much more than a mere local success. It marked the opening of a new era in copper mining. The success of the concentrator meant that ores which up to that time had been thrown on the waste dump as worthless has become of priceless value."

Somehow, during these hectic years, other extremely difficult tasks got done. After the Southern Pacific Railroad was completed across the southern end of the state, the Arizona & New Mexico was completed from Lordsburg to Clifton in 1884. The towns were supplied with water, a semblance of streets, wagon roads, stores and what of the amenities it was possible to bring to an impoverished wilderness. Both companies distinguished themselves by setting precedents of concern for their employees that have been followed and expanded upon to this day. All they asked of their men was that they do a full day's work of "getting rock in the box."

To say that the success of the sulphide concentration process made life in the Clifton-Morenci district from there on would be an exaggeration and true only in a comparative sense. The period of extreme financial stringency was over. In the years 1899, 1900 and 1901 Arizona Copper made a gross working profit of $5 million, which was more than enough to wipe out the original capital indebtedness of the company. It had started paying dividends in 1895 on the strength of the leaching plant's success, and these grew significantly after the production from the porphyry concentrator came in.

Colquhoun reports proudly that in the year 1902 the Detroit Copper Company was producing at the rate of 9,000 tons of copper per annum, and Arizona Copper at the rate of 15,000 tons. Nor is that 24,000 tons a year the slightest bit discredited by the fact that today copper production from the Morenci mine is nearly 128,000 tons a year. The present production never would have been attained if the pioneers had not done their work so well and faithfully.

Today the Phelps Dodge Corporation owns all of the mining property in the Clifton-Morenci district. It purchased the Arizona Copper Company's properties in 1921. This acquisition included the Shannon Copper Company's holdings, which Arizona Copper had bought two years earlier. In 1901 the Shannon Company, according to Colquhoun, "... appeared on the scene and signalled their entrance by purchase of the Shannon Mine and also a group of adjoining mines which we sold them and could easily spare They built their smelter and concentrator on an excellent site, just south of Clifton, and there they conducted their operations with great skill and success, until finally their ores became too low in grade to be worked at a profit. At this stage they sold out to our company."

Very shortly the total production of the area rose to about 35,000 tons of copper a year, where it stayed through 1918 and the end of World War I. The one exception was the year of 1915, when the most serious labor strike experienced in Arizona up to that time curtailed production to 25,500 tons. After that strike was settled in January, 1916, production returned to higher levels until the post-World War I depression hit in 1921-22, which cut copper production across the nation.

With the recovery of the economy, the Morenci district came back to about fifty million pounds of copper a year. But the ore that had sustained the area through the years was running out. Nor is that to be wondered at. Arizona Copper Company alone, during its forty-eight years of life, had wrested from nature's storehouse more than 460,000,000 pounds of copper. Most people during the 1920's were inclined to shrug and say, "So what? When it's gone, it's gone."

Not so Louis S. Cates. Cates served as vice-president of Utah Copper Company from 1919 to 1930. It was at Utah's Bingham Canyon mine that Danile C. Jackling and Robert C. Gemmell in 1899 had first conceived the idea of a mass production operation for the profitable mining of low-grade porphyry copper ores. It took Jackling four years to find finan - cial backers in Charles McNeil and Spencer Penrose, but his concept revolutionized the copper mining industry of the United States and made the Bingham Canyon pit the largest copper mine in the world. It also made possible the development of Morenci into the country's second largest open-pit copper mine. When Cates was made president of Phelps Dodge, in 1930, the end of Morenci's operation as a successful underground operation was clearly in sight. On top of that came the Great Depression, and Morenci was virtually shut down. Production in 1931 was 1,300,000 tons of ore and yielded a gross of only $2.57 a ton. From 1932 to 1937 only a skeleton crew was kept in the mine, and the mills were idle.

Cates and his engineering department were far from idle, however. With his intimate knowledge of the Utah Copper operation, he undertook an exhaustive, five-year exploration of the Morenci property and proved up enough low-grade ore to merit serious consideration of converting the property to an open-pit. The decision was not an easy one, for it would entail removal of some 40,000,000 tons of overburden, construction of entirely new crushing, grinding, flotation and smelting facili ties, all new mining equipment, and a gigantic investment.

Cates, however, gathered such compelling evidence that the decision was made and work was begun to develop an open-pit mine with the capacity of producing and processing 25,000 tons of ore a day. By 1942 the job was complete, at a cost of some $50 million, and in April of that year the first blister copper was produced in the new smelter.

Hardly had Phelps Dodge caught its breath, however, than the United States government, through the Defense Plant Corporation, called on Phelps Dodge to increase the 25,000-ton-per-day capacity by eighty percent! Copper is an industrial necessity during peace times; but it is vitally important for military purposes. The Defense Plant Corporation undertook to build $26,500,000 worth of additional facilities at Morenci and to lease them to Phelps Dodge. Later the company bought them outright. By 1947 the effective capacity of the reduction works had expanded to 50,000 tons of ore a day.

To a mining man the history of Morenci is a textbook on the evolution of modern open-pit copper mining and ore benefaction, while the present operation is regarded as one of the models of the industry. To the more casual observer it is a fascinating place to visit and to observe one of the nation's most important but largely unknown industries at work.

Bare statistics are totally inadequate to convey the idea of the magnitude of the operation, but they are nonetheless impressive. For instance, last year almost forty-nine million tons of material were mined. Of that, a little more than nineteen million tons was ore, the rest waste overburden that had to be removed to reach the ore. From the ore, 127,565 tons of copper were recovered, which undeniably is a lot of copper. But the complexity of the operation becomes a little more readily apparent when it is figured out that to get each pound of copper, 380 pounds of rock and earth had to be mined.

Electrical power generated by the Morenci Branch of Phelps Dodge Corporation last year was enough to serve the average needs of a community of more than 410,000 people. The company maintains for its employees 1,251 dwelling units. There were 1,900 people on the payroll last year, and they received something more than $16,500,000 in wages and salaries. That's an annual average of $8,666 per person. Considering that rents run about $30 a month for a three-bedroom house, Morenci miners are a pretty prosperous lot.

It's a far cry indeed from those early days James Colquhoun described as miserably poor. Fortunately, that gentleman, even though he retired in 1907 for reasons of health, lived until only a few years ago and thus knew the realizations of his dreams of greatness for the area. He still is remembered fondly in Clifton and Morenci, for, although he did not make his home there after retiring, he continued until his death to make annual contributions to many worthy causes in the communities for which he had done so much.

Already a member? Login ».