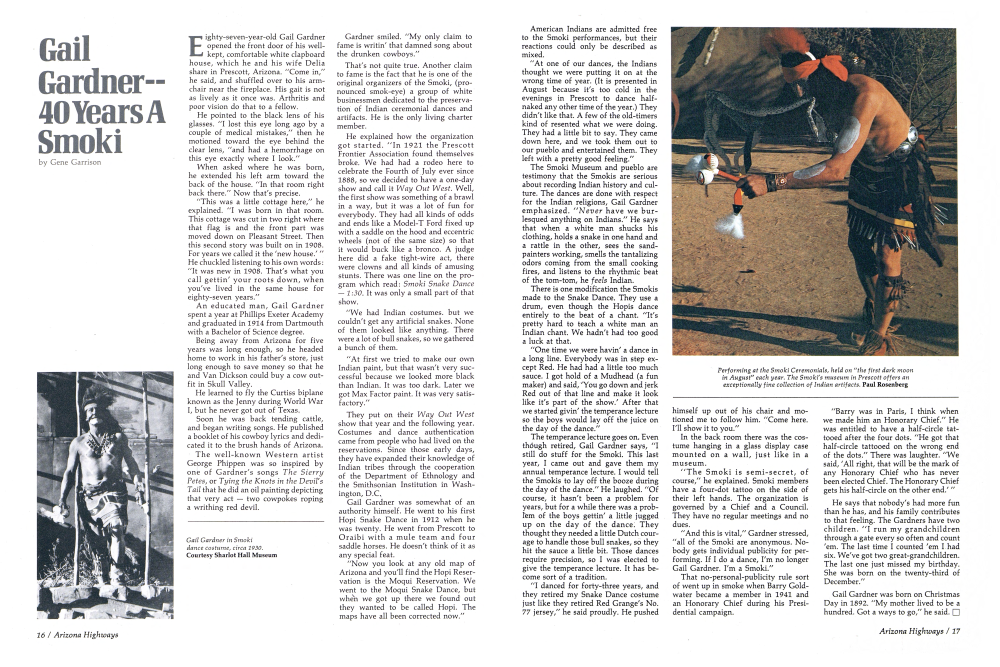

Gail Gardner - 40 Years A Smoki

Eighty-seven-year-old Gail Gardner opened the front door of his wellkept, comfortable white clapboard house, which he and his wife Delia share in Prescott, Arizona. “Come in,” he said, and shuffled over to his armchair near the fireplace. His gait is not as lively as it once was. Arthritis and poor vision do that to a fellow.

He pointed to the black lens of his glasses. “I lost this eye long ago by a couple of medical mistakes,” then he motioned toward the eye behind the clear lens, “and had a hemorrhage on this eye exactly where I look.” When asked where he was born, he extended his left arm toward the back of the house. “In that room right back there.” Now that's precise.

This was a little cottage here,” he explained. “I was born in that room. This cottage was cut in two right where that flag is and the front part was moved down on Pleasant Street. Then this second story was built on in 1908. For years we called it the 'new house.” He chuckled listening to his own words: “It was new in 1908. That's what you call gettin' your roots down, when you've lived in the same house for eighty-seven years.” An educated man, Gail Gardner spent a year at Phillips Exeter Academy and graduated in 1914 from Dartmouth with a Bachelor of Science degree.

Being away from Arizona for five years was long enough, so he headed home to work in his father's store, just long enough to save money so that he and Van Dickson could buy a cow outfit in Skull Valley.

He learned to fly the Curtiss biplane known as the Jenny during World War I, but he never got out of Texas.

Soon he was back tending cattle, and began writing songs. He published a booklet of his cowboy lyrics and dedicated it to the brush hands of Arizona.

The well-known Western artist George Phippen was so inspired by one of Gardner's songs The Sierry Petes, or Tying the Knots in the Devil's Tail that he did an oil painting depicting that very act two cowpokes roping a writhing red devil.

Gardner smiled. “My only claim to fame is writing that damned song about the drunken cowboys.” That's not quite true. Another claim to fame is the fact that he is one of the original organizers of the Smoki, (pronounced smok-eye) a group of white businessmen dedicated to the preservation of Indian ceremonial dances and artifacts. He is the only living charter member.

He explained how the organization got started. “In 1921 the Prescott Frontier Association found themselves broke. We had had a rodeo here to celebrate the Fourth of July ever since 1888, so we decided to have a one-day show and call it Way Out West. Well, the first show was something of a brawl in a way, but it was a lot of fun for everybody. They had all kinds of odds and ends like a Model-T Ford fixed up with a saddle on the hood and eccentric wheels (not of the same size) so that it would buck like a bronco. A judge here did a fake tight-wire act, there were clowns and all kinds of amusing stunts. There was one line on the program which read: Smoki Snake Dance 1:30. It was only a small part of that show.

“We had Indian costumes. but we couldn't get any artificial snakes. None of them looked like anything. There were a lot of bull snakes, so we gathered a bunch of them.

“At first we tried to make our own Indian paint, but that wasn't very successful because we looked more black than Indian. It was too dark. Later we got Max Factor paint. It was very satisfactory.” They put on their Way Out West show that year and the following year. Costumes and dance authentication came from people who had lived on the reservations. Since those early days, they have expanded their knowledge of Indian tribes through the cooperation of the Department of Ethnology and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Gail Gardner was somewhat of an authority himself. He went to his first Hopi Snake Dance in 1912 when he was twenty. He went from Prescott to Oraibi with a mule team and four saddle horses. He doesn't think of it as any special feat.

“Now you look at any old map of Arizona and you'll find the Hopi Reservation is the Moqui Reservation. We went to the Moqui Snake Dance, but when we got up there we found out they wanted to be called Hopi. The maps have all been corrected now.” American Indians are admitted free to the Smoki performances, but their reactions could only be described as mixed.

"At one of our dances, the Indians thought we were putting it on at the wrong time of year. (It is presented in August because it's too cold in the evenings in Prescott to dance halfnaked any other time of the year.) They didn't like that. A few of the old-timers kind of resented what we were doing. They had a little bit to say. They came down here, and we took them out to our pueblo and entertained them. They left with a pretty good feeling."

The Smoki Museum and pueblo are testimony that the Smokis are serious about recording Indian history and culture. The dances are done with respect for the Indian religions, Gail Gardner emphasized. "Never have we burned desqued anything on Indians." He says that when a white man shucks his clothing, holds a snake in one hand and a rattle in the other, sees the sandpainters working, smells the tantalizing odors coming from the small cooking fires, and listens to the rhythmic beat of the tom-tom, he feels Indian.

There is one modification the Smokis made to the Snake Dance. They use a drum, even though the Hopis dance entirely to the beat of a chant. "It's pretty hard to teach a white man an Indian chant. We hadn't had too good a luck at that.

"One time we were havin' a dance in a long line. Everybody was in step except Red. He had had a little too much sauce. I got hold of a Mudhead (a fun maker) and said, 'You go down and jerk Red out of that line and make it look like it's part of the show.' After that we started givin' the temperance lecture so the boys would lay off the juice on the day of the dance."

The temperance lecture goes on. Even though retired, Gail Gardner says, "I still do stuff for the Smoki. This last year, I came out and gave them my annual temperance lecture. I would tell the Smokis to lay off the booze during the day of the dance." He laughed. "Of course, it hasn't been a problem for years, but for a while there was a problem of the boys gettin' a little jugged up on the day of the dance. They thought they needed a little Dutch courage to handle those bull snakes, so they hit the sauce a little bit. Those dances require precision, so I was elected to give the temperance lecture. It has become sort of a tradition.

"I danced for forty-three years, and they retired my Snake Dance costume just like they retired Red Grange's No.

77 jersey," he said proudly. He pushed himself up out of his chair and motioned me to follow him. "Come here. I'll show it to you."

In the back room there was the costume hanging in a glass display case mounted on a wall, just like in a museum.

"The Smoki is semi-secret, of course," he explained. Smoki members have a four-dot tattoo on the side of their left hands. The organization is governed by a Chief and a Council.

They have no regular meetings and no dues.

"And this is vital," Gardner stressed, "all of the Smoki are anonymous. Nobody gets individual publicity for performing. If I do a dance, I'm no longer Gail Gardner. I'm a Smoki."

That no-personal-publicity rule sort of went up in smoke when Barry Goldwater became a member in 1941 and an Honorary Chief during his Presidential campaign.

"Barry was in Paris, I think when we made him an Honorary Chief." He was entitled to have a half-circle tattooed after the four dots. "He got that half-circle tattooed on the wrong end of the dots." There was laughter. "We said, 'All right, that will be the mark of any Honorary Chief who has never been elected Chief. The Honorary Chief gets his half-circle on the other end.'"

He says that nobody's had more fun than he has, and his family contributes to that feeling. The Gardners have two children. "I run my grandchildren through a gate every so often and count 'em. The last time I counted 'em I had six. We've got two great-grandchildren. The last one just missed my birthday. She was born on the twenty-third of December."

Gail Gardner was born on Christmas Day in 1892. "My mother lived to be a hundred. Got a ways to go," he said.

Already a member? Login ».