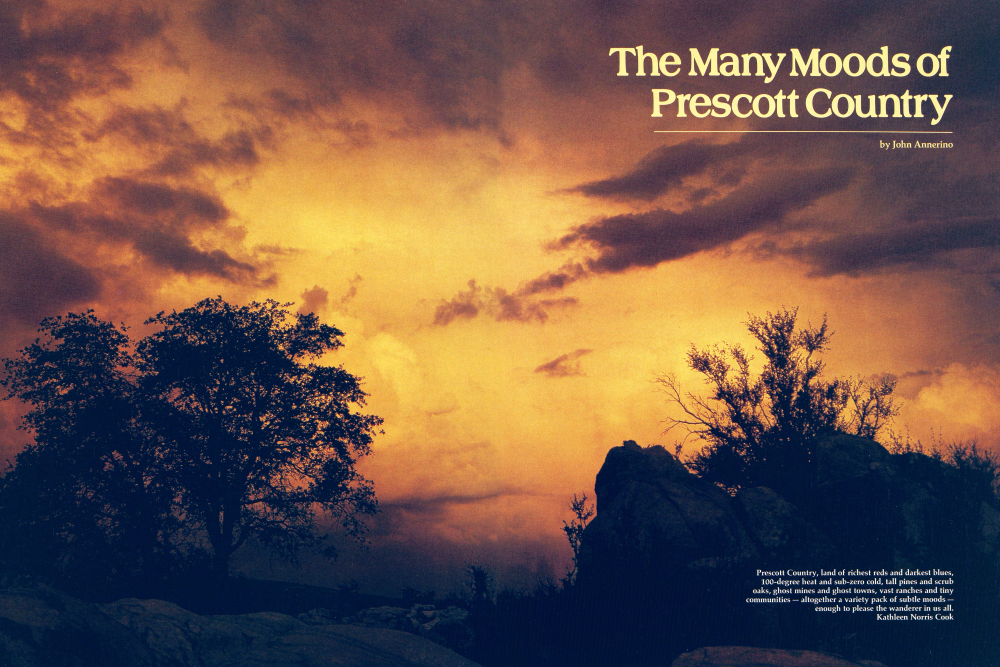

The Many Moods of Prescott Country

Prescott Country, land of richest reds and darkest blues, 100-degree heat and sub-zero cold, tall pines and scrub oaks, ghost mines and ghost towns, vast ranches and tiny communities - altogether a variety pack of subtle moods - enough to please the wanderer in us all. Kathleen Norris Cook

The spectacular wilds of Sycamore Canyon... the rich farms and ranches of the pastoral flatlands of Chino, Skull, and Lonesome valleys... colorful towns and villages only steps between yesterday and tomorrow; this is Prescott Country.

But if that's not enough of scenic attraction for you, add the tall timber of endless air-cooled forests... the worked-out mines and luckless placers of the history-rich Bradshaw Mountains, and the stark and lonely towns out of Arizona's golden past.

An extraordinary area, Prescott Country once lured only the jackass prospector and the hard-rock miner to its stoney soil. Today, however, it plays host to a variety pack of warm, friendly people: farmers and cattlemen, foresters and merchants, middle-income retireds, and a host of others. Plus an annual horde of fugitives from less fortunate climes, bent on enjoying the lush ponderosa-clad highlands during the day and the foot-stomping good times of Prescott's Whiskey Row after dark.

But how and where do you begin to explore so vast and enticing an area as Prescott Country?

On foot or horseback, I'd say. But even before you get that far, you'll need to drive at some point along the way. When you do, you might as well make use of that precious petrol and take a general survey of the land first. And there's no better place to do that than from a mountaintop.

Rising abruptly from 3000 feet in Black Canyon on its eastern flanks and 4000 feet in Peeple's Valley on its western slope, the 8000-foot-high Bradshaw Mountains are a formidable chain, stretching from Lake Pleasant to Prescott. At 7,971 feet, Mt. Union is the high point of these gold-bearing mountains.

"From Mt. Union's summit," wrote Pauline Hensen in Founding A Wilderness Capital, "one can view thousands upon thousands of square miles, not only the length and breadth of the land, but from alpine heights to distant low deserts. There is probably no better place in all Arizona to appreciate its infinite spaces and comprehend its heritage."

If the Forest Service Lookout is on duty when you arrive at the Summit of Mt. Union, and her name is Rita, she'll be happy to guide your eyes over a panoramic 360-degree tour of Prescott Country. But pay close attention. Because when she starts pointing out and naming off mountains, rivers, and mesas, as if they were vegetables in her garden, you're liable to miss an interesting feature that only someone who studies the surrounding topography 10 hours a day, 6 months of the year, could know. Just in case Rita's not on the tower, bring along the Mid-central, Map 4, available from the Arizona Office of Tourism.

Looking out from up there, fifteen miles to the south, you can see Towers Mountain standing over the embracing mesa and hill country like an old grandad. At 7,628 feet, Towers Mountain is the high point of the southern Brad-shaws and helps bring cooler temperatures to the tiny hamlet of Crown King, once a rich gold camp, and nearby Horsethief Basin Lake and Recreation Area, where almost a century ago, herds of stolen horses were corralled. Beyond the southern Bradshaws, a little to the right, you can make out the jagged tips of Wickenburg's Vulture Mountains, home of the haunted Vulture Mine and the blue dome of Phoenix' White Tanks Mountains.

"At night, the lights of Phoenix mushroom out of the desert and crawl up the Black Canyon Freeway like lightning bugs without wings," said Prescott outdoorsman Dick Yetman, who spent more than one starry night atop Mt. Union, waiting for the moon to cast its ethereal glow over Prescott Country.

Due east of your vantage point is the plateau country of Black and Crooks mesas, cut here and there by the travertines of Bishop, Silver, and Black Canyon creeks. When summer rains and heavy spring runoff fill these normally dry washes with roaring flash floods, they feed into the Agua Fria River which drains into Lake Pleasant. To the right of the New River Mountains, and beyond the mesas and travertines, is a higher flat-topped range called Pine Mountain. Established as a wilderness area in 1933, the 17,000-acre area is one of two existing wilderness areas in Prescott Country and a wonderful place to hike. If you have trouble discerning Pine Mountain from the other text continued on page 26 Chino Valley, named for its rich grama grass (local Mexicans called it "de China"), lies to the north of Prescott proper. It has been closely linked to cattle and horse rais-ing since the late 19th century. Kathleen Norris Cook (Following panel, pages 24-25) Granite Dells, earlier called Point of Rocks, is one of nature's more scenic "acci-dents," the miniature hills, mountains, and valleys creating a wonderland of rocks. Because of the many nooks and crannies available, it also became a prime place for Indian attacks. Peter Bloomer flat-topped ranges in the area, look for a little turret-shaped peak sitting on the southwest corner of the Pine Mountain Wilderness.

In 1872 Major George Randall and his troops surprised a small group of Apache Indians encamped on Turret Peak. So overwhelmed were they by Randall's daybreak attack, they hurtled themselves off the mountain.

Filling the horizon far to the east of Pine Mountain is the Mazatzal Range, a vast undulation of valleys and crests that starts northwest of Payson and continues in a southeasterly direction to the foot of the Superstition Mountains.

Swinging your gaze around to the northeast, Chino and Prescott valleys carpet the foot of Mingus Mountain and the Black Hills, two other Prescott Country recreation areas that offer camping, cool temperatures, and exceptional vistas of their own. Jerome, the former ghost-town-turned-artcolony, sits perched on the northeastern edge of the Black Hills, which stand between Prescott and the Verde Valley.

If you look carefully over the saddle between Mingus Mountain and Goat Peak, you'll see the pink sandstone Red Rock Country of Sedona.

Moving your gaze from right to left on the northern horizon, 60 miles distant, you'll see “The Peaks,” sacred to the Hopi, the Navajo, and several mountain climbers.

Nipple-topped Kendrick Peak is named after Major H. L. Kendrick who, in 1851, escorted Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves on an expedition following the Zuni, Little Colorado, and Colorado rivers to the Gulf of California. Rolling Sitgreaves text continued on page 30 (Right and below) Skull Valley, on the western flank of the Bradshaw Mountains, derives its name from two Indian battles in the 1860s, one of which involved Anglo freighters. The vanquished Indians were left where they fell. Today, the area, with its great cottonwood trees and rolling landscape, is far removed from that place of savage battle a century ago. Josef Muench / Kathleen Norris Cook The western slopes of the Bradshaws roll on into infinity in the afternoon of a summer's day. Kathleen Norris Cook Jerome. At the height of its prosperity in the early 1900s, citizens called the sprawling mining community "The billion dollar copper camp." Then, with the removal of the last ore deposits in the 30s, Jerome suddenly ceased existence, to be called by the die hard few who remained "The largest ghost city in America." Today, the ghost is slowly coming back to life, thanks to tourism. J. Peter Mortimer / Josef Muench / David Muench

Mountain looks more like a frozen blue waterfall lying on its side than a mountain. Bill Williams Mountain is named for the famed mountain man. Its snow-fed creeks form the headwaters of the Verde River.

Far to the northwest, you can see the beginnings of Chino Valley, that immense agricultural area that has its origin somewhere south of Seligman and sweeps down between six mountain ranges all the way to Granite Dells near Prescott.

West of “Big Chino” is Juniper Mesa, a 7,000-foot-high tabletop mountain. In 1979 it was submitted to Congress for approval as one of Prescott Country’s proposed wilderness areas, along with Granite Mountain and Castle Creek.

Farther to the south are the densely wooded Santa Marias. This brute drains into Granite Basin Lake. The Granite Basin area also is a preferred camping and fishing refuge for many other Prescottonians.

An arrow shot south of Granite Mountain are the Sierra Prietas, which form Prescott's western cyclorama. These “Black Mountains,” as they were known to the Spaniards, sprouted a volcanic plug called Thumb Butte, today a noted landmark.

At the very foot of the Sierra Prieta's precipitous western rim is Skull Valley. It was in that lush grazing area in 1864 that Captain Hargrave and his company of 1st California Volunteers discovered mounds of bleached skulls — hence the name. They were found to be those of Apaches and Maricopas, who had engaged in a desperate battle there over stolen horses.

Due west of Mt. Union . . . well, there are just too many mountains sticking out of the earth to single it out. But it's the upper Sonoran ranges of the Mohons, Aquarius, and the Buckskins that prevent you from seeing the London Bridge, and, at night, farther to the south, the lights of Blythe, California.

Closer to home, though, are the rugged Weaver Mountains. It was on Rich Hill near Antelope Peak in the Weavers, in 1863, that Abraham Harlow Peeples and his party gathered $4000 to $7000 (depending on who's telling the story) in gold nuggets before breakfast — if you can believe anybody would be worried about antelope jerky at a time like that. Six months later, the Weaver strike became one of the richest placer finds in Arizona history.

The sites of three ghost towns, Congress, Stanton, and Weaver, are located in the desert-dry southern foothills of the Weaver Mountains. And if you get up early enough and skulk around the nearby creek bottoms long enough, you might wash out a trace of “color” in your pan before breakfast, yourself.

Immediately adjacent to Mt. Union, still looking west, are the forested summits and ridges of Maverick Mountain, Mt. Trittle, and Lookout Mountain, each of them pock-marked with glory holes from days gone by. Straight south from the lookout tower is Moscow Peak and Longfellow Ridge, joined together by the Yankee Doodle Trail. A stone's throw east is Big Bug Mesa. Nearby Big Bug Creek was home to a horde of goldseekers in the latter 19th century, and a few glittering nuggets are still turned up every now and then. To the north is the craggy knob of Mt. Davis, a subsidiary peak of Mt. Union, named by southern sympathizers somewhat irked by the name “Mt. Union.” In fact, the only scenic areas of Prescott Country that can't be seen from Mt. Union are Granite Dells and nearby Watson, and Lynx lakes. One of them is a rock-climber's paradise; the latter two, havens for boaters and fishermen. Upon closer inspection you'll notice the pink granite humps and hollows of the “Dells” serve as a unique backdrop to Watson Lake — akin to the Needles of South Dakota's Black Hills.

And if the fish aren't biting a few miles away at Lynx Lake, you can take advantage of Lynx Lake Marina's “Moonlight Special” and row your favorite girl across the lake “by the light of the silvery moon” — providing just one more of the many moods of Prescott Country.

Already a member? Login ».