The First Southwesterners

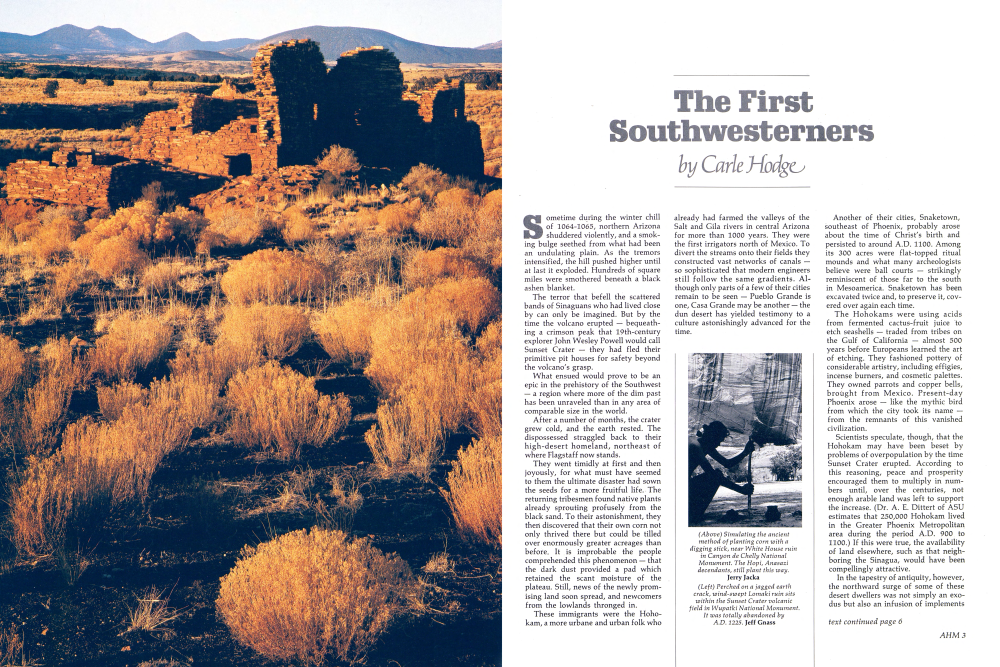

Sometime during the winter chill of 1064-1065, northern Arizona shuddered violently, and a smoking bulge seethed from what had been an undulating plain. As the tremors intensified, the hill pushed higher until at last it exploded. Hundreds of square miles were smothered beneath a black ashen blanket. The terror that befell the scattered bands of Sinaguans who had lived close by can only be imagined. But by the time the volcano erupted bequeathing a crimson peak that 19th-century explorer John Wesley Powell would call Sunset Crater they had fled their primitive pit houses for safety beyond the volcano's grasp.

What ensued would prove to be an epic in the prehistory of the Southwest - a region where more of the dim past has been unraveled than in any area of comparable size in the world.

After a number of months, the crater grew cold, and the earth rested. The dispossessed straggled back to their high-desert homeland, northeast of where Flagstaff now stands.

They went timidly at first and then joyously, for what must have seemed to them the ultimate disaster had sown the seeds for a more fruitful life. The returning tribesmen found native plants already sprouting profusely from the black sand. To their astonishment, they then discovered that their own corn not only thrived there but could be tilled over enormously greater acreages than before. It is improbable the people comprehended this phenomenon that the dark dust provided a pad which retained the scant moisture of the plateau. Still, news of the newly prom-ising land soon spread, and newcomers from the lowlands thronged in. These immigrants were the Hoho-kam, a more urbane and urban folk who already had farmed the valleys of the Salt and Gila rivers in central Arizona for more than 1000 years. They were the first irrigators north of Mexico. To divert the streams onto their fields they constructed vast networks of canals so sophisticated that modern engineers still follow the same gradients. Al-though only parts of a few of their cities remain to be seen Pueblo Grande is one, Casa Grande may be another the dun desert has yielded testimony to a culture astonishingly advanced for the time.

Another of their cities, Snaketown, southeast of Phoenix, probably arose about the time of Christ's birth and persisted to around A.D. 1100. Among its 300 acres were flat-topped ritual mounds and what many archeologists believe were ball courts strikingly reminiscent of those far to the south in Mesoamerica. Snaketown has been excavated twice and, to preserve it, cov-ered over again each time.

The Hohokams were using acids from fermented cactus-fruit juice to etch seashells traded from tribes on the Gulf of California almost 500 years before Europeans learned the art of etching. They fashioned pottery of considerable artistry, including effigies, incense burners, and cosmetic palettes. They owned parrots and copper bells, brought from Mexico. Present-day Phoenix arose like the mythic bird from which the city took its name from the remnants of this vanished civilization.

Scientists speculate, though, that the Hohokam may have been beset by problems of overpopulation by the time Sunset Crater erupted. According to this reasoning, peace and prosperity encouraged them to multiply in num-bers until, over the centuries, not enough arable land was left to support the increase. (Dr. A. E. Dittert of ASU estimates that 250,000 Hohokam lived in the Greater Phoenix Metropolitan area during the period A.D. 900 to 1100.) If this were true, the availability of land elsewhere, such as that neigh-boring the Sinagua, would have been compellingly attractive.

In the tapestry of antiquity, however, the northward surge of some of these desert dwellers was not simply an exo-dus but also an infusion of implements

text continued page 6

Already a member? Login ».