Those Who Have Gone Before Us …thoughts on land, life and legacy.

Like most busy residents of the ninth largest city in this country, we seldom make the effort to contemplate the name of our community. Phoenix. A magnificent bird of Greek mythology that rose from its own ashes to radiate in flight once again. We see before us only its present state. a brilliant plumage of vitality and dynamic growth.

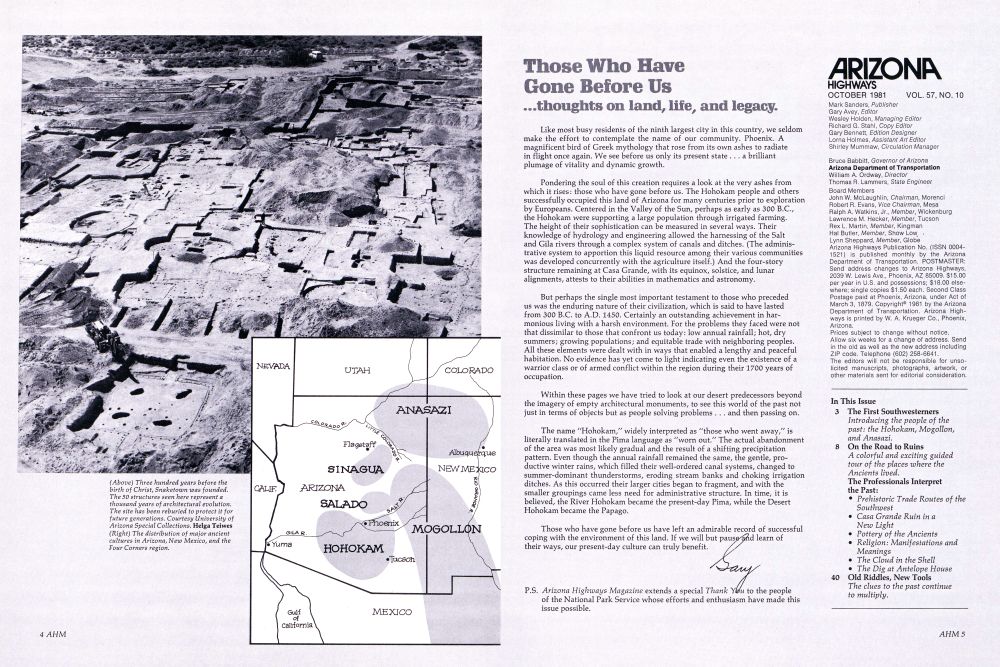

Pondering the soul of this creation requires a look at the very ashes from which it rises: those who have gone before us. The Hohokam people and others successfully occupied this land of Arizona for many centuries prior to exploration by Europeans. Centered in the Valley of the Sun, perhaps as early as 300 B.C., the Hohokam were supporting a large population through irrigated farming. The height of their sophistication can be measured in several ways. Their knowledge of hydrology and engineering allowed the harnessing of the Salt and Gila rivers through a complex system of canals and ditches. (The administrative system to apportion this liquid resource among their various communities was developed concurrently with the agriculture itself.) And the four-story structure remaining at Casa Grande, with its equinox, solstice, and lunar alignments, attests to their abilities in mathematics and astronomy.

But perhaps the single most important testament to those who preceded us was the enduring nature of their civilization, which is said to have lasted from 300 B.C. to A.D. 1450. Certainly an outstanding achievement in harmonious living with a harsh environment. For the problems they faced were not that dissimilar to those that confront us today: low annual rainfall; hot, dry summers; growing populations; and equitable trade with neighboring peoples. All these elements were dealt with in ways that enabled a lengthy and peaceful habitation. No evidence has yet come to light indicating even the existence of a warrior class or of armed conflict within the region during their 1700 years of occupation.

Within these pages we have tried to look at our desert predecessors beyond the imagery of empty architectural monuments, to see this world of the past not just in terms of objects but as people solving problems and then passing on.

The name "Hohokam," widely interpreted as "those who went away," is literally translated in the Pima language as "worn out." The actual abandonment of the area was most likely gradual and the result of a shifting precipitation pattern. Even though the annual rainfall remained the same, the gentle, productive winter rains, which filled their well-ordered canal systems, changed to summer-dominant thunderstorms, eroding stream banks and choking irrigation ditches. As this occurred their larger cities began to fragment, and with the smaller groupings came less need for administrative structure. In time, it is believed, the River Hohokam became the present-day Pima, while the Desert Hohokam became the Papago.

Those who have gone before us have left an admirable record of successful coping with the environment of this land. If we will but pause and learn of their ways, our present-day culture can truly benefit.

P.S. Arizona Highways Magazine extends a special Thank You to the people of the National Park Service whose efforts and enthusiasm have made this issue possible.

ARIZONA HIGHWAYS

OCTOBER 1981 VOL. 57, NO. 10 Mark Sanders, Publisher Gary Avey, Editor Wesley Holden, Managing Editor Richard G. Stahl, Copy Editor Gary Bennett, Edition Designer Lorna Holmes, Assistant Art Editor Shirley Mummaw, Circulation Manager Bruce Babbitt, Governor of Arizona Arizona Department of Transportation William A. Ordway, Director Thomas R. Lammers, State Engineer Board Members John W. McLaughlin, Chairman, Morenci Robert R. Evans, Vice Chairman, Mesa Ralph A. Watkins, Jr., Member, Wickenburg Lawrence M. Hecker, Member, Tucson Rex L. Martin, Member, Kingman Hal Butler, Member, Show Low. Lynn Sheppard, Member, Globe Arizona Highways Publication No. (ISSN 00041521) is published monthly by the Arizona Department of Transportation. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Arizona Highways, 2039 W. Lewis Ave., Phoenix, AZ 85009. $15.00 per year in U.S. and possessions; $18.00 elsewhere; single copies $1.50 each. Second Class Postage paid at Phoenix, Arizona, under Act of March 3, 1879. Copyright 1981 by the Arizona Department of Transportation. Arizona Highways is printed by W. A. Krueger Co., Phoenix, Arizona.

Prices subject to change without notice. Allow six weeks for a change of address. Send in the old as well as the new address including ZIP code. Telephone (602) 258-6641. The editors will not be responsible for unsolicited manuscripts, photographs, artwork, or other materials sent for editorial consideration.

In This Issue

3 The First Southwesterners Introducing the people of the past: the Hohokam, Mogollon, and Anasazi.

8 On the Road to Ruins A colorful and exciting guided tour of the places where the Ancients lived.

The Professionals Interpret the Past:

40 Old Riddles, New Tools The clues to the past continue to multiply.

The First from page 3 and ideas into a less-developed area. It was a pattern that would be repeated again and again in the ancient Southwest. At the same time, village dwellers from the northeast entered the land of the black sand, and within a generation the Sinaguan dugout dwellings had been replaced with houses of two and three rooms. Not long thereafter, apartments were installed under the cliffs in Walnut Canyon. Construction commenced on the sprawling settlement of Wupatki complete with a ball court. Nature's axiomatic fickleness was to prevail, however. Over the decades, the plateau winds slashed away the magic protective cover of the volcanic dust. As agriculture became increasingly difficult, the population slowly dissipated. Wupatki and Walnut slipped into disuse.

Some of the Sinagua descended into the more verdant Verde Valley, below the Mogollon Rim to the south. Their strongholds in the Valley, in the cliffs at Montezuma Castle, and on a hilltop at Tuzigoot, flourished after the higher country was deserted.

By the early 1200s, a visitor to the juniper slopes around Sunset Crater must have questioned, as tourists today wonder, where the villagers went - and why they left.

The Sinagua epoch, nonetheless, could be a synopsis of the life and times of the first Southwesterners: a panorama of upward struggle from a harsh hunting and foraging subsistence, the flowering of artisans and ceremonials, the rise and enigmatic decline of great stone cities.

When man first walked this region is uncertain. But he stalked mammoths and other large, now extinct creatures at least 11,000 to 12,000 years ago. That much has been determined from spear points that have been found, often with the bones of the beasts.

Analyses of their camp and kill sites tell us that they had an organized band society with an economy specialized largely toward the procurement of game animals. Specialization may have been their undoing since the environment began to change and the larger animals were replaced by smaller ones. Over the 5000-year interval that these big game hunters were in the Southwest their tools changed - Clovis to Folsom to Plano and they came to depend more on the smaller game. But, the large animals were retreating eastward and the early hunters, electing not to change their economy, followed, eventually to end up on the Great Plains.

As the lands around Arizona opened, peoples from what is now the deserts of California and northwest Mexico began to move in behind the retreating big game hunters. Already, these Desert Culture archaic peoples had developed an economy based on total environmental exploitation and succeeded where the earlier specialized groups had failed. Indeed, the Desert Culture people became the progenitors of most of the native populations that followed in the Southwest.

Archeologists think of the prehistoric Southwesterners as three general groups. There were the Hohokam, of course. At about the same time, the mountains along today's Arizona-New Mexico border were the domain of the Mogollon (roughly A.D. 1 to A.D. 1100). Finally, the Anasazi lived on the Colorado plateau of northeastern Arizona and around the Four Corners Country. Although the sequences are shadowy, there were few restraints to trade or other cultural interchange among the three areas. Not surprisingly, in view of this, the closing chapter was the most impressive.

By the year 1300, the Mogollon had moved northward to become part of remaining Anasazi groups; around 1450, the trail of the Hohokam becomes obscure. Meanwhille, masonry metropolises had burgeoned at Chaco Canyon and Aztec in western New Mexico and among the cliffs at Mesa Verde in southwestern Colorado. Artistry, architecture, and commerce reached an unparalleled peak. Chaco seems to have dominated the area's business activity for almost a millennium. But, ultimately, all these cities were deserted, Chaco and Aztec in the early 1100s, Mesa Verde in the late 1200s, Keet Seel by 1300. Why this occurred, scholars have been unable to agree. Climatic change could have contributed. Some specialists have suggested that as the population centers became more crowded, poor sanitation led to widespread disease.

A great drought gripped the region from 1276 to 1299. While many pueblos survived the drought, the advent of longer winters about 1325 left peoples in high elevations without a long enough growing season to mature their crops. The Four Corners was then emptied of the relatively few residents who remained.

One theory is proposed at Arizona State University by Dr. Christy G. Turner II. Skeletal evidence shows that many children died of anemia, and this indicates dietary deficiencies, he says. "The so-called abandonment may have been a failure of the population to reproduce itself."

Whatever the cause, the desert winds had long reclaimed the cities when the Spaniards arrived in 1540. The ruins already seemed embedded in eternity.

Already a member? Login ».