On the Road to Ruins

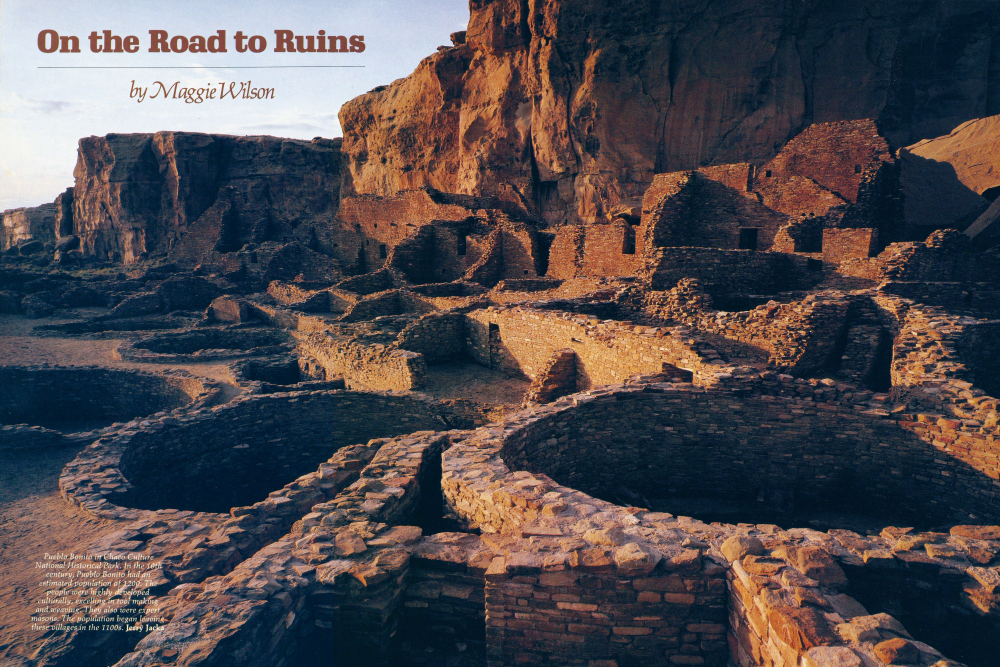

Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Culture National Historical Park. In the 10th century, Pueblo Bonito had an estimated population of 1200. The people were highly developed culturally, excelling in tool making and weaving. They also were expert masons. The population began leaving these villages in the 1100s. Jerry Jacka

haco Canyon . . . Wupatki . . . Mesa Verde . . . Hovenweep . . . Tuzigoot

Just to repeat the names is to yearn to hit the road again the road to a ruin. Any ruin. Each crumbling curiosity has its own personality, its own story to tell of hardy Southwestern pioneers of past millennia. Each inspires awe and yes, regional pride in the art, architecture, and engineering feats of this region's previous societies. The roads to ruins can be the supremely satisfying ruination of any Southwesterner who has gotten himself addicted to roaming them. My own downfall began in Globe, Arizona, in the mid-1930s. I was 10 years old, and my idol was Irene Vickery, an archeologist excavating Besh Ba Gowah in nearby Ice House Canyon. She was a small fragile woman, wearing jodhpurs and pith helmet and, as the townspeople said, "a working sonuvagun." She worked with the archeological tools of the day wheelbarrow, shovel, trowel, and sifting screen.

Day after day, I ran from home to watch her toss shovelfuls of dirt against a screen to sift out bits of jewelry, sherds of Gila polychrome pottery, corn cobs, pieces of stone hoes. As she excavated the 200 rooms and seven plazas of Besh Ba Gowah, she'd paint word pictures of the kids, dogs, and parents of 600 years ago people who, one day in A.D. 1400, had all just faded away. Why? Why did they go? Water? Firewood? Food? Disease? Internal strife? External pressure from warring groups? Assimilation? Decimation? None of the above? All of the above? Would anybody ever really know? Ah, the heady mystery of it all. That was it. I was hooked. Since then, I've run from home again and again to follow a road to a ruin. "Let's go to Chaco Canyon" is an irresistible siren call, and I never bother to ask if we'll be home by 9 a.m. Monday. No addicted ruins roamer cares about such temporal immediacies when he can go backward through the time tunnel just by standing in, say Casa Rinconada, a huge 12th century kiva built in Chaco Canyon during the heyday of the Anasazi people who, in A.D. 1300, just seemed to disappear.

haco Culture National Historical Park, New Mexico

At first blush, the trip doesn't seem worth it. The road here is unpaved, washboardy, and dusty, and it leads through an endless, broad landscape broken by dry washes and dotted with scruffy vegetation. An inhospitable hunk of real estate, an environmental disaster area. But once inside the canyon itself a mile wide, 15 miles long, and walled north and south with long rock cliffs you begin to see the series of multistoried pueblos strung along Chaco Wash. In all, there are 12 large, impressive pueblo communities and 400 smaller ruins to roam. Of all the ruins, Pueblo Bonito is best known. The D-shaped complex covers three acres and includes 800 rooms stacked as much as five stories high. Once "the largest apartment house in the world," its population peak has been "guestimated" as low as 1200 and as high as 7000. But accurate figures are hard to come by. In all the canyon, fewer than 300 graves have been found. That's a puzzling disappointment to archeologists. They say the Anasazi (unlike the Hohokam, who cremated their dead) placed their dead in a fetal position and buried them sometimes under ground-floor apartments, sometimes in rubble heaps. But here in Chaco where? Pueblo Bonito (Beautiful Village), like other complexes here Chetro Ketl, Hungo Pavi, Penasco Blanco, Una Vida, and Pueblo Alto, to name the most notable has walls constructed of hundreds of thousands of slabbed stones, ceilings for one story and floors

Already a member? Login ».