Prehistoric Trade Routes

For the next made from tens of thousands of pine logs.

So perfectly slabbed are the stones that, even after centuries of weathering, a postal card can't always be forced between them. But the Chacoans didn't leave much stonework exposed, opting instead to plaster the walls with adobe mud, sometimes mixed with gypsum to whiten the plaster.

Though scientific research during the past 100 years has been intensive, there still are no definitive answers about where the building materials came from or how they were transported.

The logs may have come from the surrounding mesas, now denuded. Trees were felled, rolled to the bluff edge, and simply pushed into the can-yon below.

To continue with that scenario: Clear cutting denuded the forests. Erosion set in. Game animals departed. Thunderstorm waters caused arroyos. Field crops washed away. Stored food sup-plies dwindled. The stressed society collapsed. Man had adversely impacted his environment.

Another scenario (anthropologists are prone to piece their facts and speculations into maybe-it-was-like-this stories): During the Anasazi golden age, Chaco was a regional trade-distribution center for an area radiating 100 miles in all directions. Full-time administrators ran the operations that stored and rerouted food supplies and goods.

With daily bread assured, there was time to devote to both crafts and arts, such as pottery and jewelry making. Time, too, to refine the socio-religious ceremonialism that was the core of everyday life. Kivas became larger, more impressive. Ceremonies became more intricate and exotic. Life was good.

That scenario prompts a look at the great kiva, Casa Rinconada. To excaby Charles C. Di Peso, Ph.D. Director The Amerind Foundation, Inc.

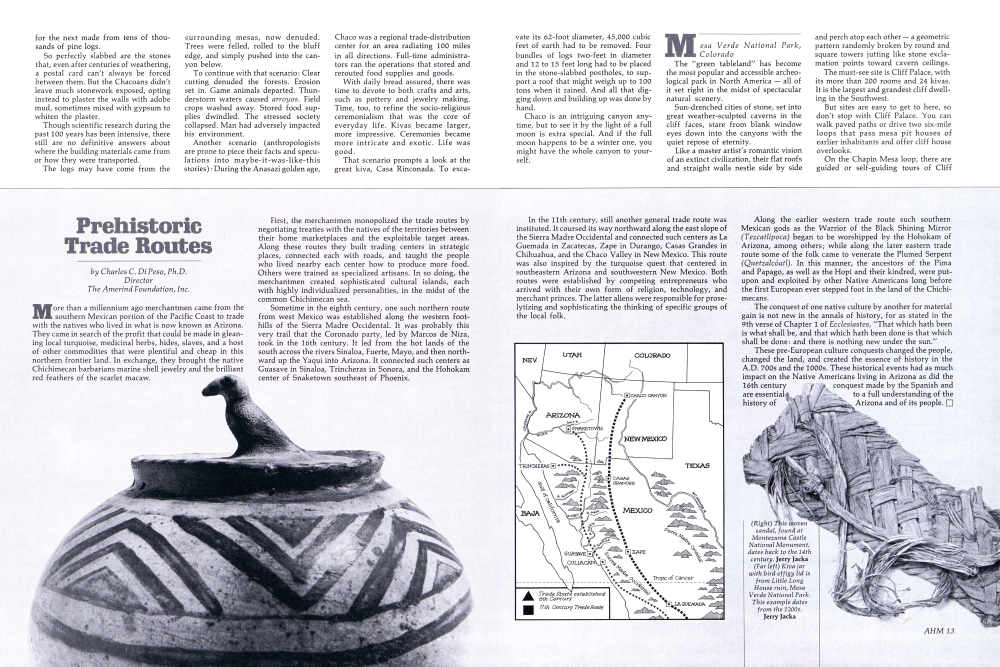

More than a millennium ago merchantmen came from the southern Mexican portion of the Pacific Coast to trade with the natives who lived in what is now known as Arizona. They came in search of the profit that could be made in gleaning local turquoise, medicinal herbs, hides, slaves, and a host of other commodities that were plentiful and cheap in this northern frontier land. In exchange, they brought the native Chichimecan barbarians marine shell jewelry and the brilliant red feathers of the scarlet macaw.

First, the merchantmen monopolized the trade routes by negotiating treaties with the natives of the territories between their home marketplaces and the exploitable target areas. Along these routes they built trading centers in strategic places, connected each with roads, and taught the people who lived nearby each center how to produce more food. Others were trained as specialized artisans. In so doing, the merchantmen created sophisticated cultural islands, each with highly individualized personalities, in the midst of the common Chichimecan sea.

Sometime in the eighth century, one such northern route from west Mexico was established along the western foot-hills of the Sierra Madre Occidental. It was probably this very trail that the Coronado party, led by Marcos de Niza, took in the 16th century. It led from the hot lands of the south across the rivers Sinaloa, Fuerte, Mayo, and then north-ward up the Yaqui into Arizona. It connected such centers as Guasave in Sinaloa, Trincheras in Sonora, and the Hohokam center of Snaketown southeast of Phoenix.

Excavate its 62-foot diameter, 45,000 cubic feet of earth had to be removed. Four bundles of logs two-feet in diameter and 12 to 15 feet long had to be placed in the stone-slabbed postholes, to support a roof that might weigh up to 100 tons when it rained. And all that digging down and building up was done by hand.

Chaco is an intriguing canyon anytime, but to see it by the light of a full moon is extra special. And if the full moon happens to be a winter one, you might have the whole canyon to yourself.

Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado

The "green tableland" has become the most popular and accessible archeological logical park in North America all of it set right in the midst of spectacular natural scenery.

Sun-drenched cities of stone, set into great weather-sculpted caverns in the cliff faces, stare from blank window eyes down into the canyons with the quiet repose of eternity.

Like a master artist's romantic vision of an extinct civilization, their flat roofs and straight walls nestle side by side and perch atop each other a geometric pattern randomly broken by round and square towers jutting like stone exclamation mation points toward cavern ceilings.

The must-see site is Cliff Palace, with its more than 200 rooms and 24 kivas. It is the largest and grandest cliff dwelling ing in the Southwest.

But sites are easy to get to here, so don't stop with Cliff Palace. You can walk paved paths or drive two six-mile loops that pass mesa pit houses of earlier inhabitants and offer cliff house overlooks.

On the Chapin Mesa loop; there are guided or self-guiding tours of Cliff In the 11th century, still another general trade route was instituted. It coursed its way northward along the east slope of the Sierra Madre Occidental and connected such centers as La Guemada in Zacatecas, Zape in Durango, Casas Grandes in Chihuahua, and the Chaco Valley in New Mexico. This route was also inspired by the turquoise quest that centered in southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico. Both routes were established by competing entrepreneurs who arrived with their own form of religion, technology, and merchant princes. The latter aliens were responsible for proselytizing and sophisticating the thinking of specific groups of the local folk.

Along the earlier western trade route such southern Mexican gods as the Warrior of the Black Shining Mirror (Tezcatlipoca) began to be worshipped by the Hohokam of Arizona, among others; while along the later eastern trade route some of the folk came to venerate the Plumed Serpent (Quetzalcoatl). In this manner, the ancestors of the Pima and Papago, as well as the Hopi and their kindred, were putupon and exploited by other Native Americans long before the first European ever stepped foot in the land of the Chichimecans.

The conquest of one native culture by another for material gain is not new in the annals of history, for as stated in the 9th verse of Chapter 1 of Ecclesiastes, "That which hath been is what shall be, and that which hath been done is that which shall be done: and there is nothing new under the sun."

These pre-European culture conquests changed the people, changed the land, and created the essence of history in the A.D. 700s and the 1000s. These historical events had as much impact on the Native Americans living in Arizona as did the conquest made by the Spanish and are essential to a full understanding of the Arizona and of its people. 16th century history of

Palace, Balcony House, Spruce Tree House, and Square Tower House; on the Wetherill Mesa loop, of Step House and Long House. Additionally, no trip to Mesa Verde is complete without a visit to the 8572foot north rim for a panoramic view of mountains, mesas, and the sea of desert beyond.

As for Mesa Verde's history: Basketmakers came into the area late, about A.D. 600, or 800 years after they'd colonized nearby canyons. From A.D. 600 through the 1100s, Mesa Verdeans lived on the mesas. Only in the last 100 years of their occupation, the 1200s, did they build and live in the large cliff dwellings. But even then, most continued to live in small pueblos consisting usually of 12 rooms and one kiva.

The population exodus began as a trickle in A.D. 1050 and built to a steady flow during the Great Drought of 1276 to 1299.

The mesa remained abandoned until the 1880s when Richard Wetherill, a Mancos, Colorado, rancher, happened upon them while looking for strays. He and his brothers untrained but eager were the first excavators. Since then, few areas in the Southwest have been so thoroughly studied as Mesa Verde.

Hovenweep National Monument, Colorado

Hovenweep is a Ute Indian word meaning "deserted valley." Like other Anasazi settlements, it is believed to have been abandoned during the Great Drought. This national monument straddles the Utah-Colorado border and consists of six clusters of ruins notable for their "castles" and for towers unlike any others in the Southwest.

The castles are massive masonry pueblos built on mesa rimrock; the windowless towers square, round, oval, and D-shaped are built in the canyons below, often with a disdain for foundation leveling. What was the purpose of the towers? Were they silos? Water reservoirs? Ceremonial "cathedrals"? Dwellings? Observatories? One currently favored belief is that they comprised line-of-sight signal towers, part of a communications system linking various Anasazi settlements.

Curious as the structures here are, scientists have almost ignored Hovenweep since 1919, when the Smithsonian Institution published an archeological survey. The general public has shunned it, too, perhaps because of its remoteness and its unpaved roads.

Aztec National Monument, New Mexico

Several summers ago, in a Farmington, New Mexico, coffee shop, we fell into conversation with a couple from California who were planning to visit Aztec ruins the following day. And the husband was resisting the junket.

"Ellie's idea of fun," he said, "is to go see an old rockpile built by some dumb yahoos who didn't even have the wheel."

"Now, Sam," Ellie cajoled, "it's part of our American history and heritage." As an aside to us, she said, "I'm a teacher, and I always try to go places where I can take pictures to show the class."

The next day we saw Sam again, clutching a guidebook and wandering delightedly from room to room of a reconstructed wing of an Aztec pueblo. (Ellie, was off taking pictures somewhere.) "Wow," he grinned, "doesn't it do something to you to think you're standing where people lived 800 years ago? Why, did you know they had to carry their building logs and firewood from the forest 20 miles away? I can just see them, tending their patches of corn,beans, and squash on terraces down by the river. And that church-in-the-round out there in the plaza a great kiva, it says here listen, they say that the roof weighs 90 tons. And to think they didn't even have the wheel. And these doorways are probably so tiny because they didn't want to let the cold air in."

Aztec will do that to you. Its reconstructed rooms give little lessons in Anasazi life-style at a glance; the rebuilt kiva offers vivid impressions of religious ceremonialism in its fullest expression; the excavated ruins, some with their tiny doorways sealed with stone and mortar, add the prescribed intrigue, and the visitors center museum with its many artifacts provides interpretation of what you see.

Perhaps those tiny sealed doorways were the ancient equivalent of the modern homeowner locking his door during brief absences. For the ancient ones, the time away from home became eternity.

But Sam did have some kindly things to say about archeologists. "A lot of these buildings had fallen down into heaps, see? And they had to dig out the dirt and put the logs and bricks back into place. They must be the only guys in the world who start at the top of the heap and work down."

Already a member? Login ».