Pottery: Utilitarian Values, Artistic Treasures

Change is a universal phenomenon. It can take place in the smallest fraction of a second or over millennia depending upon the attributes we wish to examine and the scale on which they are measured. Change, then, is at the root of discovery. An analysis of that characteristic of pottery can provide clues to the many roles played by ceramics throughout out its 2000-or-so-year history in the Southwest.

Probably, pottery making was not an independent invention in the Southwest but owes its presence here to Mesoamerican contacts. The faltering experimental steps characteristic of a new craft appear to be missing; the earliest examples discovered already display sophisticated workmanship. As the ideas spread, adapting pottery making to local resources did result in short periods of crude beginnings as the people learned the limits of the local materials. The rapid development of many forms, finishes, and decorative styles suggests that, once accepted, pottery rapidly fulfilled needs or that values came into existence because of its presence.

At first, the spread of pottery making seems to accompany other traits associated with a commitment to a more settled existence and, like the concept of sedentism, ceramics did not spread over the Southwest at a uniform rate. A labor trade-off is involved; that time expended making pottery is taken away from food production important to a people with a hunting-gathering economy. Similarly, the more complex the processes of manufacture become adding polishing, slip-ping, and decorating the more time-consuming is the craft. The extent to which finish and decoration developed in the Southwest suggests that utilitarian aspects became supple-mented by artistic considerations which, in themselves, served an important role among past societies.

With the accumulation of information from archeological investigations in the Southwest has come the realization that a much more complex organization existed than we previously supposed. Ceramics seem to reflect this complexity but in different ways among the various cultures. Early in their history the Hohokam appear to have had specialists making painted ceramics which became part of a formalized trade system. Peoples in central Arizona made mostly plain or redslipped ware and received decorated pottery from elsewhere. The Mogollon peoples had a long history of art that was regionally distinct but maintained ties to northern Mexico.

Somewhat greater diversity exists among the Pueblo people. It is believed that the earliest decorated types were produced in only a few centers. However, the contacts through food exchange led to widespread distribution of styles. By the late A.D. 1000s, complex centers began to emerge and unique styles of decoration accompanied that development.

As some centers declined, others came into existence, each with styles that might mark community or ethnic identity. High status burials often have ceramics that are exotic examPiles.

Piles. The A.D. 1300-1400 period brought many population rearrangements and the beginning of pueblo specific identity.

It is from this condition that the distinctive artistic expressions of today have developed.

The advent of metal and other durable containers brought about a decrease in the utilitarian aspects of Indian pottery.

Nevertheless, the strong roots of social identification and the availability of an artistic field, on which a translation of their physical and social environment can be expressed, remains. Experimentation on that field still occurs, and it serves to continue an identity in the long tradition of artistic treasures.

Ruins continued from page 14

Betatakin and Keet Seel, Navajo National Monument, Arizona There's a theory among purists that ruins can't be really appreciated unless you suffer to get to them. Suffer means hike, climb, crawl, horseback, swim, or otherwise exert yourself.

Our family has split 50-50 on that theory.

My son walked out the back door of the visitors center here, down a short, paved trail to an overlook from which he viewed Betatakin ruins, nestled in a cavern across the canyon. He says he was impressed - “really, Mom, impressed” with the fragile beauty and hearty history of the place.

A half-hour later he was lolling in an air-conditioned motel room in Kayenta.

To see Keet Seel, eight miles away, I spent an entire day suffering a horseback ride on a strong-willed nag in a saddle too big and stirrups too long. The one bright spot on that bone-jarring 17-mile round trip through beautiful Tsegi Canyon was the Navajo Indian guide. When I asked him to “sing a little Navajo saddle song,” he obliged with a lusty rendition of “Rhinestone Cowboy.” Over and over again.

But Keet Seel was worth it. Nestled, like Betatakin, under the shelter of a large cliff alcove, its 155 rooms and six kivas comprise the largest and bestpreserved cliff dwelling in Arizona. For the visitor (only 20 per day during the summer season) it has an air of isolation, yet intimacy. A place to climb ladders to ledge houses, Indian-style, to put hands on the walls and sootstained cavern, to gaze out over a lovely valley cut by a stream and flanked by cottonwoods and grassy meadows.

Amazingly, both Keet Seel and Betatakin were occupied for no more than 40 years, from 1260 to 1300 a short term, indeed, in view of the creative energy that was expended in building them.

As elsewhere, the late 14th century drought is given as one reason. A change in precipitation patterns is another. According to that scenario, heavy rains after the period of drought resulted in erosion which lowered the water table or, if the people survived that event, shortly thereafter there came a time when the longer winters reduced the growing season to the point where many crops could not mature.C anyon De Chelly National Monument, Arizona By auto, a 22-mile rim drive lets you stop and gaze into the canyon 1000 feet below and to cliff walls opposite, where stony alcoves cradle cliff dwellings.

By foot, you can take a 2.5-mile round trip hike from White House Overlook down to White House Ruins. The hike takes two hours.

Guides with open vehicles also may be reserved in advance by those who want a view from the bottom or closer looks at the many ruins and the famed rock art that decorates the canyon walls.

The art some painted on with natural dyes, some pecked into the sandstone of the cliffs includes numerous panels created by Basketmakers, Anasazis, Pueblos, and Navajos, consecutive occupants of the canyon since the birth of Christ.

Canyon de Chelly (pronounced de shay; a Spanish corruption of the Navajo word “tsegi,” meaning rocky canyon) offers relief to eyes that have stared at red rocks for miles en route. The relief is green - green grass, green trees, and the green valley floor where

Religion-- Manifestations and Meanings

by Barton Wright, Anthropologist San Diego Museum of Man Scattered across the Southwest on desert plain, on mesa top, and in sheltering canyon walls, the ruins of impressive villages turn their blank windows to the world or sprawl like the moldering bones of great dinosaurs. The varying tones of pottery shards enhance innumerable slopes and dunes; a profusion of unknown symbols embellish the sun-blackened rocks of desert and mountain. An occasional undisturbed trail, flanked by a cairn of stones, strikes toward a distant horizon; carefully hewn toeholds mount a cliff wall to some hidden destination, reminders that for millennia mountain and desert belonged to a people whose lives were shaped and molded by the bare bones land and its elemental forces.

These people, who lived by and with the earth, developed a highly complex and sophisticated cycle of rituals.

Their respect for and involvement with the supernatural is seen in every element of their daily existence. For unlike our modern day culture, they made no separation between the religious and secular parts of their lives.

The kiva, or subterranean ceremonial chamber, is the most prominent feature found in the abandoned cliff dwellings of the Anasazi. For the men it was a place where the ritual demands of their religion could be satisfied without interference. Every line and feature of that space reflected their concepts and beliefs.

The strangely shaped doorways of the pueblo, through which the women passed at their work, were openings constructed as much in response to religion as to practicality. Maidens bending their backs to grind corn did so beneath the fructifying symbols of carefully painted clouds. The children played with toys decorated in colors of religious significance. No action took place that did not consider the relationship between people and supernaturals.

Although the villages are now untenanted, their people passed from view, they are not mute, for every line and perspective speaks of those who once lived within.

The well-worn trails to distant neighbors are marked by cairns of small stones, remnants of a belief that began with a feather reverently placed at the shrine of some beneficent spirit to make the load light and the trip easy. Each journey on these trails ended with the traveler rubbing a stone across his aching body to remove his weariness. Then the stone was placed on a pile of similar pebbles before the traveler trotted into the village with renewed vigor.

Undeciphered symbols abound, pecked through the agedarkened surface of boulders and cliff faces to expose the lighter rock beneath, or painted in earth colors on overhanging canyon walls. They are graphic images of mythic systems intimately related to the ritual life of prehistoric people, a record of lost beliefs.

Dancing figures in endless repetition, staring monsters, and abstractions of reality adorn the fragments of pottery that litter the ground chosen as a homesite, each of these bespeaking a potter's esthetic portrayal of an element of prehistoric cosmology.

Many remnants of religious beliefs remain for the inter- nested and observant to note and admire, but these are the merest shadow of those which existed before. The people who left behind these religious artifacts were strong in their commitment to their beliefs, beliefs which had given them aid.and comfort in their effort to survive in this beautiful but harsh land.

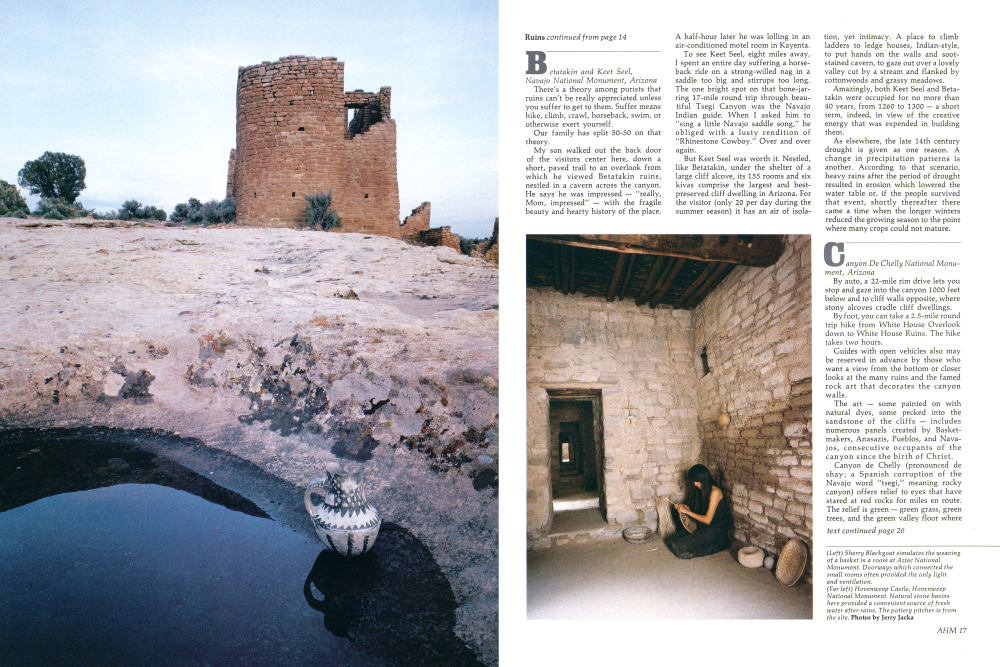

West of Kayenta, Arizona, in Navajo National Monument, are the great cliff-pueblos of 13th century Keet Seel, below, and Betatakin, right. Both are picturesquely situated in the red sandstone walls of Tsegi Canyon. Jeff Gnass Carrying water to one's village, simulated in the photo at bottom, was undoubtedly a never-ending job in prehistoric times. Pottery containers of various sizes and shapes were used to hold water, but it was probably carried in large jars called ollas. Photographed in Canyon de Chelly National Monument. Jerry Jacka

The Dig at Antelope House

The early morning phone call clearly foretold how our digging in Canyon de Chelly would go that day in 1972. “Nelson Rockefeller will be visiting Antelope House today; if you find something nice, could you leave it in place for him to see?” asked the superintendent. I thought this a very reasonable request, but I knew that all we would show the Governor and his family would be broken pottery, corn cobs, and perhaps a sandal or two.

In the south plaza, our dig tested, probed, and pitted a vast layer of turkey dung. Our research questions answered, only cleanup and a few details remained. I huddled briefly with the crew chief, Pam Magers, about the work of the day. We decided to remove a small remnant against the pueblo wall, if only because the dry turkey dung would eventually slump as future visitors toured the ruin.

I went on to other problems.

Before long it was 10:30; today was my turn to give the daily tour. Walking by the south plaza, I saw the crew standing in a tight knot around the turkey dung pillar. Pam was on her knees, working even more intensely than usual. On a dig where well-preserved basketry and sandals were found everyday, she had made an outstanding find. Emerging from the dust and debris was a twine-wrapped rectangular basket with a patched and worn cotton cloth placed over the top, all of it tied so tightly with yucca cordage that, with appropriate postage, it could have been mailed from the Chinle Post Office that evening. On the side of the basket stood a series of four-footed animals. Unprecedented! But what was this thing?

The basket/bundle had been buried. Could we detect the outline of the pit that had been dug, determine the level from which the pit began, and thus date the time of burial? The basket had provided one more piece of the giant jigsaw puzzle that was Antelope House. Unless we recorded it carefully, we would not be able to fit the basket into its proper place in the developing picture. The mundane bookkeeping tasks helped us restrain our mounting wonder and curiosity.The Rockefellers arrived in the midst of a beautiful quiet sunset just as we were ready to move the basket into our field lab. Their questions and curiosity mirrored those building within us throughout the day. We returned to camp late that night, weary, but fulfilled and excited.

Several days later, when we unwrapped the bundle, we were to find animal skin bags, a large conch shell, a strange string of quartz crystals, and a perfect ear of corn encircled by macaw feathers - all tied to a hematite rod and to a string of turquoise beads. A century ago, Alexander Stephen had described similar ceremonial ears of corn at a Hopi village. More Antelope House turquoise and shell came from within the basket than was found throughout the rest of the site.

Still later, the expert analysis of James Adovasio revealed that pulverized turquoise had been used to produce one of the pigments used for the figures on the basket. He says this basket is the most outstanding specimen from the Southwest he has ever seen, and he has seen them all.

Even after years of analysis and study, questions remain. Why was the basket buried? Was it done during a desperate emergency or as part of a ceremony, as the population abandoned the site? Was it an act of reverence, or one of convenient disposal? What caused the makers and users of this rich trove to give it up? Perhaps we will never know.

by Don P. Morris, Archeologist Western Archeological and Conservation Center

Ruins from page 17

modern Navajos' crops and orchards grow.

A pastoral scene withal, it seems somehow to join now with then. A timeless continuum in a spectacularly scenic setting.

Bandelier National Monument, New Mexico While Canyon de Chelly is a visual, romantic tie of then and now, the ruins in Bandelier are the real threads that tie past cultures to present ones.

Though the Rio Grande settlements had developed from a base rooted in the Mogollon culture, they were given impetus during the 1200s by the arrival of dislocated Anasazi, many of them from Mesa Verde, who superimposed their own socio-religious organizations and the vestiges of their once grand architecture onto the Mogollon foun-dation.

These structures, built during the 1300s, were occupied until about 1500, a half-century before the Spanish arrived.

Where they went from here is no mystery: Their descendants are Pueblo people living today in the nearby villages of San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, and Cochiti. Their basic life-style, farming methods, religious ceremonialism, and (until recent decades) architecture and pottery styles spell out their ancestry as surely as a diagrammed and certified family tree.

Adolph Bandelier, a Swiss-American, began anthropological exploration of this area in 1880. His discoveries, in turn, made him a Southwestern legend. He is also notable as the region's first archeological scenario writer, detailing how life was lived by the prehistoric people he studied.

His main theory appeared in book form as a novel, The Delight Makers, which (though out of print) is still regarded as the definitive work about the life and times of Tyuoni and Frijoles, two major ruins in this monument that bears his name.

The 42-square miles of the preserve, with its 65 miles of trails, is a place where you can spend as little time as an hour (in which case, spend it in Frijoles Canyon) or as much as a week.

Whichever, pretty country, pueblo ruins, cave dwellings, rock art, religiousshrines, and quiet canyon crevices abound.

Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, New Mexico

The Mogollon (pronounced muggy-ohn) were mountain people whose origins are lost. On this side of the Mexican border, they were relatively undistinguished as a group, over-shadowed and later absorbed by the ambitious and productive Hohokam and Anasazi. South of the border, they had a more illustrious history as merchants, traders, engineers, farmers, and builders of a city called Casas Grandes (no relation to Arizona's Casa Grande), a bustling commercial center that had large marketplaces, warehousing facilities, ities, plazas, ball courts, condominiums, underground sewers, and aqueducts.

But to give the Northern Mogollon their due: Their culture is considered the cradle of Southwest Indian culture. They were the first to cultivate corn, make pottery, build pit houses, establish villages, and the first to abandon the nomadic life of hunting and gathering.

Today, only one Mogollon Culture site, Gila Cliff Dwellings, has been developed for public viewing.

Another of the off-the-beaten-path preserves, these ruins consist of 40 masonry rooms built inside five deep caves. The structures were begun in 1280 and abandoned in 1400. They are remarkably well preserved (Opposite page) One of the later flowerings of the Pueblo Culture occurred at Bandelier National Monument. Some of the ruins here date back to the 12th century. The larger pueblos, Tyuonyi and Tsankawi, were occupied until A.D. 1550.

The prehistoric polychrome pottery bowl is from the Rio Grande region of New Mexico.

(Below) The only Mogollon Culture site open to the public is at Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. The 40 rooms built inside caves were abandoned about A.D. 1400.

(Above) A sampling of the Saladoan diet includes, clockwise from top, mesquite beans, ground corn, dried beans, saguaro fruit, and prickly pear fruit.

(Left) The Saladoans were Pueblo people who built their cliff dwellings along the Salt River in the Tonto Basin, where they lived between A.D. 1250 and 1400. The area is now Tonto National Monument.

(Right) A Tonto polychrome long necked vase, dated A.D. 1300-1400

Photos by Jerry Jacka

(Following panel) Wupatki Hunters, by Ted Blaylock, Acrylic, 24x36 inches.

Already a member? Login ».