Old Riddles, New Tools

Old Riddles, New Tools by Carle Hodge

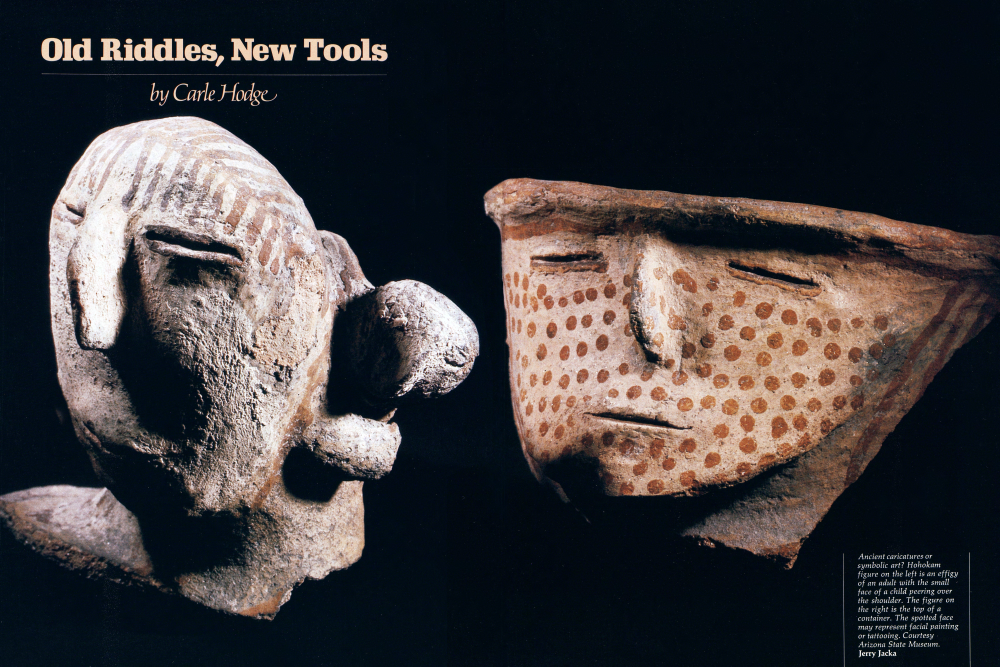

When Dr. Emil Haury returned to excavate the Hohokam site of Snaketown, southeast of Phoenix, for the second time, in the mid-1960s, his students at the University of Arizona gave him a silver trowel engraved with these words from Shakespeare's Julius Caesar: "You are not wood, you are not stones, but men." "A better epigram for the archeologist's work has never been written," Haury remarked later. But the Bard's admonition also could serve as an ironic reminder of the state of the science in the Southwest. Of the wood and stones they left behind, much is known. The prehistoric men themselves, though, remain remarkably elusive. Even after almost three-quarters of a century of excavation and analysis, the rise and fall of the region's rich prehistoric cultures are shrouded with the unexplained. In general, the researchers concur on the origin of the original Americans. Our earliest immigrants came many millennia ago across a Bering land bridge from Siberia. Arizona State University's Dr. Christy G. Turner II is comparing ancient Asian teeth with aboriginal American teeth, hoping to find exactly where that primal journey began. But what inspired, much later, the transition from small clusters of rude pit houses to great stone cities with elaborate ceremonial chambers? And why were those cities deserted? Where did their inhabitants go? "In the period culminating in the Anasazi area in the 13th century and in the Mogollon area in the 14th century, there was an abrupt aggregation of small units of population into very big towns, a shift over one or two generations," Dr. William Longacre, University of Arizona points out. "All sorts of notions" have been proposed for this, he says, "ranging from banding together for protection, to response to some kind of environmental stress, but none of this is well documented." The ultimate tale of the city dwellers is equally enigmatic. Because of similarities in pottery and other cultural manifestations, the consensus is that the builders of the great villages of the Anasazi were the progenitors of the modern Pueblo peoples. When Europeans arrived in the Salt and Gila river valleys, the peaceful Pima were irrigating vast acreages of corn and beans and wheat, often using canals that had been built by the Hohokam hundreds of years earlier. Perhaps they were, in fact, the same tribe. While some of his colleagues disagree, Haury, the dean of Hohokam scholars, is convinced they were. Yet, if the Pima, who lived in small villages, were rooted in the Hohokam, one would have to explain the disappearance of the large artistic Hohokam towns. Clearly, the residual mysteries are many. Fortunately, archeologists have modern methods and new instruments with which they may solve some of them. Carbon-14 dating permits the pinpointing of events much farther back in time than was possible previously. Pollen scientists now can disclose what plants people grew or gathered at specific times. A vast network of trade roads constructed by the canny entrepreneurs of Chaco Canyon, the commercial center of ancient New Mexico, was known from the earliest scientific expeditions. But photographs from Earth-orbiting satellites have shown the network to have been much more extensive than was thought. One of the most important archeological tools is not new at all, however, having emerged in the late 1920s.

Two of the near-legendary giants of their profession were toiling, at the time, in northwestern New Mexico. Earl Morris was unveiling the remnants of the city at Aztec, and Neil Judd those of Pueblo Bonito and Chaco Canyon, when identical letters reached them from Dr. Andrew Ellicott Douglass at the University of Arizona in Tucson. "I thought you might be interested to know that the latest beam in the ceiling of the Aztec ruins was cut just exactly nine years before the latest beam from Bonito. Most of the other wood shows contemporaneous occupation." Morris and Judd were not simply ecstatic. They were amazed. Douglass, an astronomer, had succeeded where generations of archeologists had merely met frustration. He had fit, or at least he had started to weave, the chronology of prehistory into the Christian calendar. His technique of tree-ring research made it possible to date pre-Columbian sites. Archeologists now would say with text continued on page 46

Already a member? Login ».