General Gadsden's Purchase

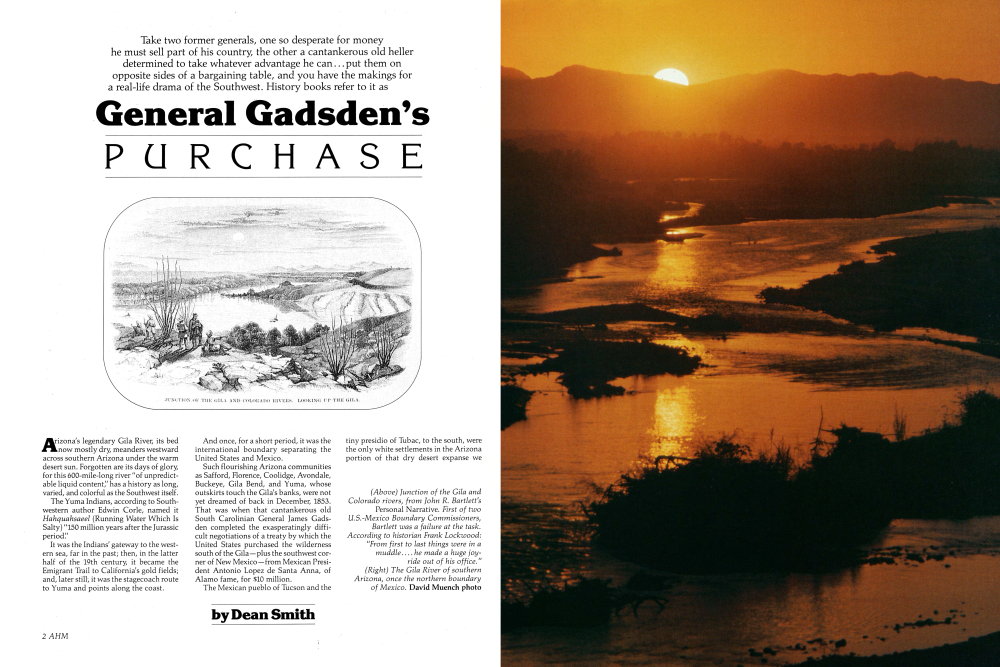

Take two former generals, one so desperate for money he must sell part of his country, the other a cantankerous old heller determined to take whatever advantage he can...put them on opposite sides of a bargaining table, and you have the makings for a real-life drama of the Southwest. History books refer to it as Arizona's legendary Gila River, its bed now mostly dry, meanders westward across southern Arizona under the warm desert sun. Forgotten are its days of glory, for this 600-mile-long river "of unpredictable liquid content," has a history as long, varied, and colorful as the Southwest itself.

The Yuma Indians, according to Southwestern author Edwin Corle, named it Hahquahsaeel (Running Water Which Is Salty) "150 million years after the Jurassic period."

It was the Indians' gateway to the western sea, far in the past; then, in the latter half of the 19th century, it became the Emigrant Trail to California's gold fields; and, later still, it was the stagecoach route to Yuma and points along the coast. And once, for a short period, it was the international boundary separating the United States and Mexico.

Such flourishing Arizona communities as Safford, Florence, Coolidge, Avondale, Buckeye, Gila Bend, and Yuma, whose outskirts touch the Gila's banks, were not yet dreamed of back in December, 1853. That was when that cantankerous old South Carolinian General James Gadsden completed the exasperatingly difficult negotiations of a treaty by which the United States purchased the wilderness south of the Gila-plus the southwest corner of New Mexico-from Mexican President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, of Alamo fame, for $10 million.

The Mexican pueblo of Tucson and the tiny presidio of Tubac, to the south, were the only white settlements in the Arizona portion of that dry desert expanse we now call the Gadsden Purchase.

The Gadsden Purchase

The famed Kit Carson, who really should have known better, assured the U.S. Senate that the area was so God-forsaken a wilderness that "not even a wolf could make his living upon it."

The seeds of the Gadsden Purchase saga were sown in the mistakes of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican War in 1848. Because of an error in J.D. Disturnell's map, which was used in the postwar boundary survey, some 6000 square miles of the fertile Mesilla Valley were claimed by both Mexico and the United States. To support their claims, both Governor W.C. Lane of New Mexico and Governor Angel Trias of Chihuahua, Mexico, summoned troops to the area. The situation awaited only some emotional incident to plunge the United States and Mexico into another war.

When Franklin Pierce became president in March, 1853, he faced up to that explosive problem and others. Although he was a New Hampshire man, Democrat Pierce was much under the influence of the southern wing of his party. He appointed Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, the future president of the Confederate States of America, as his secretary of war and leaned heavily on Davis in reaching many momentous decisions. Pierce also took Davis' advice and replaced his minister to Mexico, New Yorker Alfred Conkling, with the fiery Gadsden of South Carolina.

Gadsden, a former Army general and close friend of Andrew Jackson, had gone into railroading and was an ardent advocate of a southern transcontinental railway route, which he believed would help the South gain economic parity with the

THE GADSDEN PURCHASE and the BOUNDARY CONTROVERSY THE SOUTHERN BOUNDARY

(Above) If Mexican President Santa Anna had not declined the U.S.'s offer, Lower California as well as a huge section of northern Mexico (shaded area) would have become American Territory. (Right) Following the short-lived Mexican War (1846-48), three adjustments occurred in the southern border of the United States before a final boundary was ratified.

(Top, left) Picacho Peak, in southern Arizona, was in its time an ancient reference point, resting place for the Mormon Battalion and Lt. Michler's Boundary Survey crew, site of the westernmost engagement of the Civil War, stage stop, and today, a state park along Interstate 10, between Phoenix and Tucson. Alan Manley photo (Left) The desert Southwest. To Kit Carson and others, it was a "land not even a wolf could make a living upon." David Muench photo

The Gadsden Purchase

North. He was such a vociferous advocate of southern interests that he often castigated John C. Calhoun, a vehement Southern rights supporter, for being too moderate in defending slavery and states' rights. Despite bitter opposition from Northern politicians, who wanted no further slave territory added to the nation, Pierce instructed Gadsden to bargain with Santa Anna for purchase of land that would settle the Mesilla Valley dispute and get the railroad right-of-way.

When he arrived in Mexico City, in August, 1853, Gadsden immediately sized up Santa Anna's situation. It was a desperate one. The Mexican dictator needed money-lots of it-to put down a smoldering revolution and maintain himself in power. With Pierce's full backing, Gadsden made a breathtaking proposal: The United States would pay $50 million-more than twice the total annual revenues of the Mexican government-for 120,000-square miles of Mexican territory. The area reached southward, comprising much of the states of Coahuila, Nuevo Leon, Tamaulipas, Chihuahua, Sonora, and all of Baja California. If Santa Anna would not agree to so mammoth a cession, Gadsden was to press for lesser options, five in all, with smaller payments.

Much as he hated the Norte Americanos, Santa Anna needed money so badly he was strongly considering the maximum land sale. But at that moment American adventurer William Walker led a filibustering expedition to the southern tip of Baja California and proclaimed an independent republic there. The news of Walker's audacity so infuriated Santa Anna he closed his mind to any major land cession. "I could probably have obtained Lower California had not the insane [Walker] expedition caused Santa Anna to set his face against it," Gadsden later told the Charleston, South Carolina, Daily Courier.

Gadsden ranted and threatened the Mexicans with an American grab of the coveted territory, but Santa Anna would consent only to the smallest of the Pierce options. "No treaty on these limits (the nearly 30,000 square-miles eventually agreed upon) can prove other than a temporary expedient," Gadsden warned, hinting darkly of an American takeover. But Santa Anna stood firm.

The Gadsden Treaty was signed on December 30,1853. In it the United States agreed to pay $15 million for a slightly larger area than the present Purchase. The Mexicans gave up their Mesilla Valley claims and other rights. But Santa Anna insisted on keeping Baja California and the land bridge connecting it with the rest of Mexico.

That is why the present U.S.-Mexico boundary angles northwest from near Nogales to the Colorado River, south of Yuma, and does not give the United States a seaport on the Gulf of California. Santa Anna reasoned (probably correctly) that if Baja California were separated from Mexico's main body, it would soon become a U.S. territory.

Fanciful legends sprang up about the boundary surveyors getting drunk on tequila and angling northwest toward the Colorado. But it was Santa Anna's foresight, not liquor, that established the boundary we know today.

The U.S. Senate, split between North and South, argued the treaty ratification for many weeks, finally agreeing to move the boundary a bit north (to its present location) and to cut the payment to $10 million. By the spring of 1854, Santa Anna was so desperate for money he accepted the reduced offer, thus enraging many Mexican patriots who were determined to cede no more of their national territory.

"With knife in hand, the United States was attempting to cut yet another piece from the body it had just mutilated," Santa Anna explained to his angry countrymen. At least, he said, he had avoided another disastrous war and perhaps an even bigger American territorial grab. On June 29, 1854, President Pierce signed the amended treaty. Juan Almonte, Mexico's minister to the United States, was waiting at the Treasury Department door the next morning to pick up the first payment of $7 million.

After many months of discussion and amendment, the new boundary had been set: Commencing in the middle of the Rio Grande River at 31° 47' north latitude, then west for 100 miles, then south to 31° 20', then west to the 111th meridian of longitude; from there on a straight line to a point in the middle of the Colorado River 20 English miles south of the junction of the Gila with the Colorado, then north up the Colorado to the old treaty line dividing California from Baja California.

Major William H. Emory, Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, was appointed by President Pierce as U.S. boundary survey commissioner as well as chief surveyor and astronomer. With his Mexican counterpart, Jose Salazar y Larregui, he started laying out the new boundary in the spring of 1855, moving westward from El Paso, erecting rude stone markers at intervals of 20 to 75 miles along the way.

At the same time, Lieutenant Nathaniel Michler was sent to Fort Yuma, across the Colorado River from the present city of Yuma, Arizona, to survey the boundary southeastward toward Los Nogales.

Postscript: It was not until March 10, 1856, two years after the signing of the amended treaty, that the Mexican garrison at Tucson evacuated the town, much to the dismay of local citizens who were left unprotected from Apache raiders. And it was not until November 14, 1856, that three U.S. Army companies commanded by Major Enoch Steen arrived in Tucson to run up the American flag.

(Left) Sketch from Boundary Commissioner John Bartlett's Personal Narrative. On June 17th, 1852, Bartlett and his entourage, which was "found to be utterly useless in running and making a boundary," according to Lockwood, started from Yuma on the return trip to the East, making "leisurely advances and frequent halts," among which was a visit to the Pima Villages, perhaps near present-day Phoenix. (Right) The boundless grasslands of southeastern Arizona, where once Spanish land grant cattle kings held sway, became part of the United States with the $10 million Gadsden Purchase. The treaty, signed by President Pierce on June 29, 1854, was for many years a point of serious contention in government circles.

Peter Kresan photo (Below) Cottonwood trees near Patagonia, part of the incredible scenic beauty of southern Arizona. Gill Kenny photo

Already a member? Login ».