The Gadsden Purchase Survey

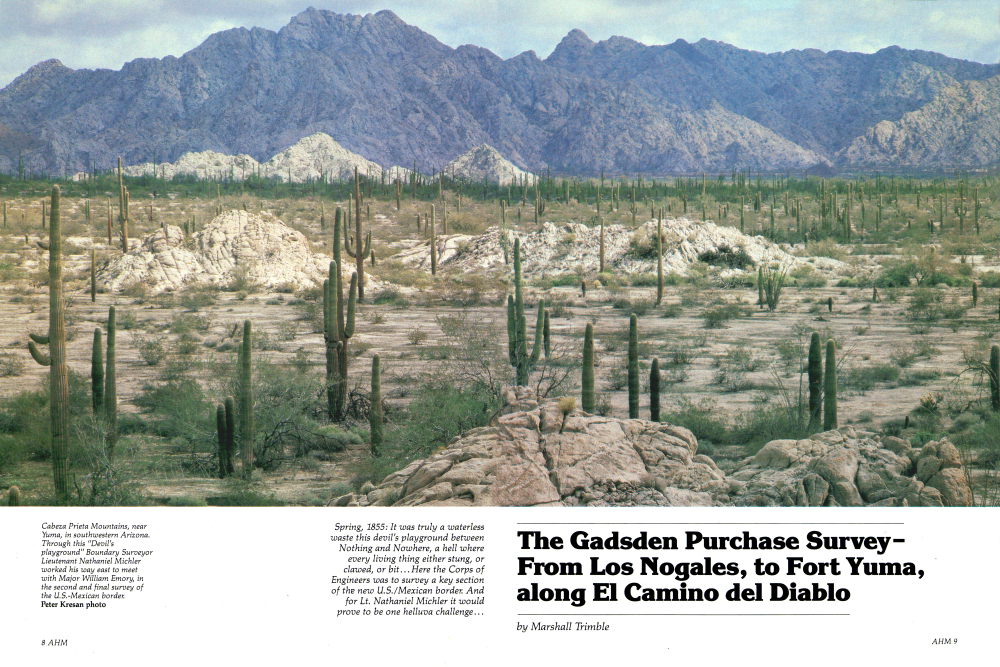

Spring, 1855: It was truly a waterless waste this devil's playground between Nothing and Nowhere, a hell where every living thing either stung, or clawed, or bit... Here the Corps of Engineers was to survey a key section of the new U.S./Mexican border. And for Lt. Nathaniel Michler it would prove to be one helluva challenge...

The Gadsden Purchase SurveyFrom Los Nogales, to Fort Yuma, along El Camino del Diablo

It was the summer of 1855 when Lieutenant Nathaniel Michler blinked through the sting of salt sweat as he gazed out across the vast arid expanse of hot desert southeast of old Fort Yuma and wondered aloud what had possessed his government to acquire such a godforsaken piece of real estate. Ten million dollars for this waterless wasteland, and every living inhabitant either stings, claws, or bites! Ranges of stark, jagged mountains were separated by wide, forbidding deserts...the lowest elevations seemingly devoid of life. Closer to the mountains, mesquite and paloverde stood defiantly against the harsh landscape. Off in the distance, resinous creosote bushes clung with a death-like grip to the bleak slopes of desert mountains. Humble little desert flowers, almost invisible to the naked eye, bloomed briefly before dissipating in the intense heat. Omnipresent prickly pear, cholla, and dagger-like agave dotted the gray-buff expanse of desert. It was truly a devil's playground, and Michler, a member of the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, was going to mark a trail through it. He must have felt closer to hell than he'd ever been before. But he had a job to do: survey a line along what was to be the last unresolved boundary of the continental United States, and this bleak, waterless waste between Fort Yuma and Nogales would be the Commission's greatest challenge. The Corps of Engineers, which was given the difficult task of surveying Mr. Gadsden's new acquisition, was composed of young soldier-scientists chosen from among the top graduates of West Point. The American West's rendition of Renaissance Men, they combined science with the romance and color of the fabled Mountain Men, fighting hostile Indians and battling hardships and hunger. The man in charge of the boundary survey was the recognized authority on the 1500-mile Mexican border, Major William Emory. The scion of a distinguished Maryland family, Emory attended West Point where his gallant manner and grim determination earned the slender red-headed young warrior the nickname "Bold Emory!" Emory, who fought in the war with Mexico in 1846, is better remembered for the scientific notes he took while crossing the Great Southwest with General Steven Watts Kearny, commander of the Army of the West, during the Mexican War, 1846-48. His report, The Notes of a Military Reconnaissance, submitted to Congress at the war's end, provided the first accurate map of the new acquisition which had been heretofore "terra incognita." It gave detailed descriptions of the natural resources, flora, fauna, and native inhabitants. These pioneering studies earned him a permanent place in the most respected scientific circles of the world. A previous attempt to survey the boundary line between the U.S. and Mexico had ended in chaos. One of the reasons was the inexperience and incompetence of the boundary commissioner, John R. Bartlett. Bartlett's successor, Major William Emory, was a no-nonsense professional. His single-minded mission was to establish a reliable boundary line, come hell or high water. After completing the difficult task of surveying the twisting, shifting waters of the Rio Grande, he began making plans for marking the boundary west from El Paso. Before leaving Washington for Texas, Major Emory ordered Lieutenant Michler to proceed immediately to Fort Yuma, on agave dotted the gray-buff expanse of desert. It was truly a devil's playground, and Michler, a member of the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, was going to mark a trail through it. He must have felt closer to hell than he'd ever been before. But he had a job to do: survey a line along what was to be the last unresolved boundary of the continental United States, and this bleak, waterless waste between Fort Yuma and Nogales would be the Commission's greatest challenge. The Corps of Engineers, which was given the difficult task of surveying Mr. Gadsden's new acquisition, was composed of young soldier-scientists chosen from among the top graduates of West Point. The American West's rendition of Renaissance Men, they combined science with the romance and color of the fabled Mountain Men, fighting hostile Indians and battling hardships and hunger. The man in charge of the boundary survey was the recognized authority on the 1500-mile Mexican border, Major William Emory. The scion of a distinguished Maryland family, Emory attended West Point where his gallant manner and grim determination earned the slender red-headed young warrior the nickname "Bold Emory!" Emory, who fought in the war with Mexico in 1846, is better remembered for the scientific notes he took while crossing the Great Southwest with General Steven Watts Kearny, commander of the Army of the West, during the Mexican War, 1846-48. His report, The Notes of a Military Reconnaissance, submitted to Congress at the war's end, provided the first accurate map of the new acquisition which had been heretofore "terra incognita." It gave detailed descriptions of the natural resources, flora, fauna, and native inhabitants. These pioneering studies earned him a permanent place in the most respected scientific circles of the world. A previous attempt to survey the boundary line between the U.S. and Mexico had ended in chaos. One of the reasons was the inexperience and incompetence of the boundary commissioner, John R. Bartlett. Bartlett's successor, Major William Emory, was a no-nonsense professional. His single-minded mission was to establish a reliable boundary line, come hell or high water. After completing the difficult task of surveying the twisting, shifting waters of the Rio Grande, he began making plans for marking the boundary west from El Paso. Before leaving Washington for Texas, Major Emory ordered Lieutenant Michler to proceed immediately to Fort Yuma, on the banks of the Colorado River. At that juncture, he was to begin marking a boundary line in a southeasterly direction toward Emory's westbound party. They were expected to join forces somewhere near today's Nogales. Michler boarded a sailing ship in New York, on September 20, 1854, bound for San Diego, California, via Panama and San Francisco. On his arrival, he made the necessary purchases of mules, wagons, and provisions for the expedition. Teamsters, cooks, and laborers were hired, and a military escort was provided at San Diego. By November 16, the party was on the move toward Fort Yuma, a distance of 217 miles. They were the most difficult miles he'd ever traveled, Michler later reported. On December 9, they arrived at the Fort and spent the next few weeks recruiting and re-equipping the beleaguered expedition. Unknown to young Michler, the worst was yet to come. In the spring, he optimistically set out across El Camino del Diablo (the Devil's Highway) to rendezvous with Emory's party. For Michler, the bleak stretch of arid land between Fort Yuma and the small Mexican rancheria at Sonoita, about halfway to Los Nogales, presented a particular challenge. His hope for success depended on summer storms filling the natural reservoirs along the way. If they didn't, things could become critical quickly. Tinajas Altas, (High Tanks), along El Camino del Diablo, which roughly follows today's international boundary, was one such place. There were five levels of reservoirs in the granite slopes. The lower levels were the first to run dry. Travelers passing through late in the season had to scale the steep-sided inclines to reach water. Michler's report mentions encounters with some of these travelers: “On our way...we met many emigrants returning from California, men and animals suffering from scarcity of water. Some men had died from thirst and others were nearly exhausted.” But not all were men. “Among those we passed between the Colorado and the Tinajas Altas was a party composed of one woman and three men, on foot, and a packhorse in wretched condition carrying them all. The men had given up from pure exhaustion and laid down to die; but the woman animated by love and sympathy, had plodded on over the long road until she reached water, then clambering up the side of the mountain to the highest tinaja, she filled her bota, (a sort of leather flask), and scarcely stopping to take rest, started back to resuscitate her dying companions. When we met them she was striding along in advance of the men, animating them by her example.”

The Gadsden Purchase Survey

East of Tinajas Altas lay the dreaded Lechuguilla Desert where dark volcanic lava beds stretched for miles. The land became so desolate even the hardy creosote bush withered. Further east lay the equally tough Tule Desert and beyond that the Agua Dulce Mountains. The last spring before reaching Sonoita, was Quito-baquito, about 15 miles to the west. There, the worst part of the journey was over or just beginning-depending on which direction you were traveling.

It was the sparseness of this desert land that later inspired Michler to write: "There is no grass, but a sickly vegetation, more unpleasant to the sight than the barren earth itself!" He found that, even though the sweeping desert winds sometimes obscured the road, it was well-marked by the unending array of bleached bones of horses and cattle.

In the spring of 1855, Michler ran low on supplies about halfway to his destination, and he was forced to return to Fort Yuma.

Supplies were not easy to come by at the Fort...especially for the mules. There Michler paid 12 cents a pound for barley and $100 a ton for hay shipped all the way from San Francisco.

What happened next is not recorded. But for some reason, Michler had a change of mind. He decided to give up the idea of surveying from the Fort to Los Nogales. Instead, he chose to take a milder but roundabout route to the border town, from which point he would then survey north-west toward Fort Yuma.

In late spring, he packed his wagons and headed north along the Colorado River to its junction with the Gila River, which he would follow east to Maricopa Wells and the Pima villages (near present-day Phoenix), some 200 miles away. From thevillages, he would then head south toward Tucson and, ultimately, Los Nogales.

Michler and his party followed the Gila route across some 110 miles of steep grades and rocks where wagons had to be pushed uphill and lowered by rope, inching down-hill a step at a time, creaking and scraping over the rocky trail. Thirty miles farther on, they came to the great bend in the Gila and crossed the 40-Mile Desert, arriv-ing at the Pima Villages bone weary, saddle-sore, and much in need of rest.

The Lieutenant had much admiration for the Pimas. During his visit with them, he noted in his journal "...they are fur-ther advanced in the art of agriculture, and are surrounded with more comforts than any uncivilized Indian tribe I have ever seen. Besides being great warriors, they are good husbandmen and farmers... the women are very industrious, not only attending to their household duties, but they also work superior baskets, cotton blankets, belts, etc. Their huts are very comfortable, being of oval shape, not very high, built of reeds and mud and thatched with tule or wheat-straw. They are the owners of fine horses and mules, fat oxen and milch cows, pigs and poultry, and are a wealthy class of Indians!"

Earlier, during his travels east through the Gila Valley, Michler had noted their crops of wheat curing in the sun; rich cultivated fields of cotton, sugar, peas, corn, and melons irrigated by miles of acequias (ditches) - "A view," he wrote, "differing from anything we had seen since leaving the Atlantic States."

After taking leave of the Pimas, Michler began the 70-mile journey south to the Mexican pueblo of Tucson. About 35 miles down the trail, he passed a towering monolithic volcanic upheaval the Mexicans simply called Picacho (peak).

Here where several years earlier the Mormon Battalion had stopped to rest from the building of a wagon road to California, the Butterfield Overland would later build a stage station, and the westernmost battle of the Civil War would be fought. Today, Picacho is still significant, serving as a welcome rest stop for weary motorists traveling Interstate 10 between Phoenix and Tucson.

Michler spent most of the month of June, 1855, in Tucson enjoying the hospitality of the town as a guest in the home of presidio commandant Captain Hilarion Garcia.

Tucson at the time was a small pueblo with a population of some 350 citizens. Its wide, dusty streets were lined with low, flat-roofed adobe buildings.

Off to the north, the lofty, pine-covered Santa Catalina Mountains dominated the vista. To the south were the jagged peaks of the Santa Rita range. Beyond, huge billowing clouds formed each afternoon signaling the beginning of the welcome summer rains that drifted in from the Gulf of Mexico. Michler anxiously awaited these showers. They would fill the tinajas along Camino del Diablo.

When learning that Emory's party had finally reached Los Nogales, 69 miles to the south, Michler packed his equipment and resumed his journey. Along the way, he passed the Mission of San Xavier del Bac, the first of two missions between Tucson and Los Nogales, ceded to the Papago Indians by the Mexicans. "A beautiful church," he wrote in his journal, "with its exterior walls richly ornamented, carved and stuccoed, and the interior handsomely decorated and painted in bright colors, with many paintings in fresco...."

Tubac, Arizona's other non-Indian village, was deserted when Michler arrived. "The wild Apache lords it over this region, and the timid husbandman dare not return to his home," he wrote in his journal.

A few miles farther south, at the Mission of Tumacacori, Michler found the ancient church and rich farm lands aban-

The Gadsden Purchase Survey

abandoned by all but two or three hardy Germans. These men, far from home, were braving the constant Apache menace while searching for gold and silver in the nearby mountains. After a short visit, Michler pushed on again to rendezvous with Major Emory.

At Los Nogales, his change in route explained and accepted by Emory, the two men determined the latitude and longitude of the intersection of the parallel and meridian and erected a pyramidal monument of stone. When Michler began his planned survey back toward the Colorado River, the summer rainy season began, which assured water along the drier parts of the trek.

West of Nogales and the Santa Cruz River, Michler noted the mineral wealth of the area. In the Atascosa Mountains, west of Tubac, "rich mines of copper, silver, and gold, are said to exist. Its mineral resources have not yet been thoroughly examined on account of the Apache indians." During the next few years, American and Mexican miners would extract gold and silver from the mountains, on both sides of the Santa Cruz River.

Marking the diagonal line to the Colorado River was rough going, with craggy, steep-sided canyons and mountains impeding progress. At times, the party barely averaged five miles a day.

While camped in a pretty, live-oakstudded valley, in the vicinity of the San Luis Mountains, the surveyors found that the desert's life-giving monsoon weather could also have a nasty side.

The wispy, innocent-looking clouds that appeared over the mountains to the southeast gave little hint of the gathering storm. Then, a panoramic brown curtain of dust moved swiftly across the land, causing the durable saguaro to quiver in its path. A wailing wind accompanied by rolling thunder and brilliant flashes of chain lightning signaled Nature's rendition of the Fourth of July. From beneath the mass of clouds, a long, dark veil draped. The storm was brief but furious. Water off the barren slopes and hard-packed ground filled dry arroyos and turned them into raging muddy torrents. Cactus, boulders, and anything else that got in the way were swept up in the turbulence. Michler called the storm that blew over his tents, flooded his camp, and washed away some of his equipment a hurricane, and he wasn't far from wrong. It was one more example of the desert's unpredictable nature. But despite the inconvenience, the rain was welcome relief from the blistering heat, which had already reached 110 degrees Fahrenheit in the shade.

Michler also reported sighting some "strange specimens of natural history" around the San Luis Mountains, including what the Mexicans called "El Scorpion." He described it as "a large, slothful lizard in the shape of a miniature alligator, marked with red, black, and white belts." It seems he might have gotten his notes confused, and some 20th century writers have perpetuated the error. Michler's scorpion was a Gila monster.

The Americans also had encounters with another denizen of the desert: the rattlesnake. "The glare of our fires attracted a large number," he wrote. "The whole place seemed infected with them. We judged them to be a new species from their tigercolored skins; they are exceedingly fierce and venomous... we had often seen others with horns, or small protuberances above the eyes; and Dr. Abbott had taken from the body of still another species quite a number of small ones, among which was a monstrosity with two perfectly formed heads attached to one neck.

"When you lie down on your blankets, stretched on the ground, you know not what strange bedfellow you may have when you awake in the morning," Michler added. "My servant insisted upon encircling my bed with a reata of horse-hair to protect me from their intrusions. Snakes are said to have a perfect repugnance to being pricked by the extremities of the hair." (The myth is still with us today!) Thanks to an abundant rainfall that summer of 1855, Lieutenant Nathaniel Michler was able to complete his survey along the Camino and record the best and worst of the land's dramatic contrasts. His travels took him across desolate, for-lorn deserts; through rugged mountains; and over volcanic lava beds completely devoid of life. He saw fields and mines that had once thrived, but now lay abandoned because of the restive Apaches.

But Michler also correctly perceived a land of promise in the Gadsden Purchase. Native peoples were farming the rich, fertile river valleys. The mountains were a veritable lode of gold, silver, and copper. And some of the Southwest's finest grazing land could be found on the gentle, grass-carpeted plains and valleys.

But, the lonesome and forlorn desert described in Lieutenant Nathaniel Michler's journal, however, just might prove to be the greatest natural treasure of all: mankind's last refuge, an uncluttered habitat where one can go to sort things out; a place unconquered where man is forced to live in harmony. In the desert there is elbowroom, something that is rapidly becoming one of the world's scarcest commodities. The sandy soil dotted with cholla, ocotillo, agave, paloverde, mesquite, and things with other melodious Spanish names will never be turned upside down by the farmer's plow nor will it feel the weight of concrete, glass, steel, and asphalt.

In high praise of the unharnessed wilderness traveled by Michler and others, desert defender John C. Van Dyke wrote in 1901, "The deserts should never be reclaimed, they are the breathing spaces of the West and should be preserved forever."

Already a member? Login ».