Monuments and Memorials of the Gadsden Purchase

Thanks to those few farsighted individuals who gambled and won the wealth of an entire region 130 years ago, there are now a half-dozen varied and beautiful natural wonders preserved forever in that bright land south of the Gila.

The Monuments and Memorials of the Gadsden Purchase

If James Gadsden and the United States Senate had not added 29,640 square miles to our nation by purchase in 1853-27,305 of those miles are in Arizonathere would be no Casa Grande National Monument to remind us of the canal-building Hohokam Indians, the first Americans to show how irrigation can transform the desert. The Spanish colonial thrust into and through Sonora would have left no traces within the state's borders. The range of the Apaches in the United States would have been sharply reduced; there would have been no Fort Huachuca, no Fort Bowieand what would that have done to Hollywood? Finally, those pervasive photographs of giant saguaro and organ pipe cacti, silhouetted boldly against flaming sunsets, would bring to mind the exotic wonders of northwestern Mexico, not of the American Southwest.

Thanks to James Gadsden, however, those things are now part of Arizona's rich and varied heritage, accessible to everyone in half a dozen national monuments and memorials administered by the National Park Service. Without the images they evoke, the state would be much poorer.

Fittingly, the first monument established in the area honors Arizona's original agriculturists, the Hohokam. (The word, borrowed from present-day Pima Indians, is accented on the last syllable and means things that are “used up” and gone.) Not many years ago, archeologists believed that the Hohokam evolved from a primitive Desert Culture People who, on obtaining corn and a knowledge of irrigation from Mexico, developed a sophisticated culture of their own. Newer theories hold that the founders of the civilization themselves migrated north from Mexico, bringing with them their engineering skills and hardy varieties of seed. The penetration may have occurred as early as 300 В.С. By the year A.D. 1000, the Hohokam were living in widespread villages of pithouses-shallow depressions, some oval, some square, some rectangular, topped by timber-supported domes of earth with smoke holes in the top. They dug extensive ditches to water food-stuffs and cotton, the last of which they wove into cloth and traded with other tribes miles away. In addition to being expert potters, they used a weak acid for etching seashells brought from the Gulf of California - a feat accomplished hundreds of years before the art of etching was known in Europe. The unearthing of huge unroofed oval courts and the discovery of solid rubber balls suggest that they may have played strenuous games that perhaps had ceremonial importance.

A little after A.D. 1300, they began building, in one of their villages just north of present-day Coolidge, a massive structure known since Spanish times as Casa Grande. The accomplishment staggers the imagination. The Hohokam had no metal tools, no beasts of burden, no wheels for transporting heavy weights. Lacking stone nearby, they built thick walls out of a mixture of mud and caliche, an earth substance that turns quite hard on drying. Each course was piled on by hand to a height of about two feet and allowed to dry before another course was added. Meanwhile other workers went with stone axes to a stand of trees southeast of Casa Grande, hacked down material for rafters and beams and dragged the timber to the site where it was to be used. The bottom floor of the building con-sisted of five rooms that were filled with earth to create a platform 40-feet wide and 60 long. On this platform two more stories were erected; these were then topped with a single-room penthouse whose outer walls were pierced with a variety of holes. Several theories have been offered to explain this mysterious skyscraper in the desert. One arises from the fact that some of the holes in the outer walls of the upper room seem to have been aligned in such a way that village priests could determine, by celestial observations, the exact dates on which religious ceremonies were to be held. The priestly class responsible for those ceremonies may have lived at Casa Grande.

Whatever its purpose, Casa Grande, along with the neighboring villages, fields, and canals, was abandoned by 1450. Again many theories have been offered-soil impregnated with alkali by overuse, drought, or even an invasion by outsiders, though no signs of warfare have been discovered. The theory generally favored today holds that changes in rainfall pat-tern filled the Gila River with silt that clogged the canal system with more mud than the labor force could remove as promptly as needed. Farmers began shift-ing to small plots closer to the river, and food production became a family effort that no longer needed the sophisticated social organization that formerly had controlled the distribution of agricultural products and water. Civilization regressed, and the Hohokam became, it is widely believed, the progenitors of today's Pima and Papago tribes. Bleak and empty though it was, Casa Grande remained so impressive that in 1892 Arizona protected the site by reserv-ing 400 acres around it. In 1903 a roof was built over the crumbling mud as a defense against weather. Fifteen years later, the reservation was incorporated into the National Park system. In time a new roof replaced the old, and a museum was added to tell, through artifacts and graphics, the story of the first modernists in the South-west, as far as the tale is known today.

Arizona's Coronado National Memorial, one of 22 memorials in the United States and another benefit arising from the Gadsden Purchase, stretches out for five miles along the Mexican border between Nogales and Bisbee. (National memorials commem-orate notable people and events, whereas national monuments preserve distinctive sites.) The easiest way to reach Coronado is to drive west from Bisbee, in southeast-ern Arizona, along State Highway 92, to the memorial's Montezuma Canyon entrance. Another seven miles, partly paved, partly dirt, climb through the south-ern Huachuca Mountains to a parking area in Montezuma Pass. From there a short trail leads to the top of Coronado Peak, 6880 feet above sea level.

Standing on the summit, feeling the sun and wind, and soaking in the giant panorama of broad valleys and folded hills, it is easy to slip backward, in imagination, 443 years and reconstruct the initial European penetration of what became the American Southwest. The seven legendary cities of golden Cibola, somewhere to the north, were the lure. In 1540, young Francisco Vasquez de Coronado was placed

in command of an army of a thousand men, most of them cooperative Mexican Indians, and told to invade the province. When reconnaissance parties brought back conflicting reports about the route, Coronado left the main army behind while he pushed ahead with a picked vanguard of 80 horsemen, 30 foot soldiers, and several Indians.

The logics of geography insist that both the advanced group and the main army, which followed a few months later, must have used as their entry into the unknown lands the broad valley of the San Pedro River, flowing northward past today's high-perched memorial. But alas for hope. The Spaniards found no gold, though they pushed with great effort and suffering as far as present-day Kansas. In 1542, they returned to Mexico in disgrace. But they had discovered how vast and varied the northern reaches of the continent werereason enough for this stunning natural memorial that celebrates what we now realize was a resounding success in the history of exploration.

Sometimes on still nights, legend avers, a soft chime of bells hovers over the partially restored mission church of Tumacacori, in the Santa Cruz Valley, 18 miles north of the boundary established by the Gadsden Purchase. Supposedly the sound emanates from bells that were hidden in the desert by the mission's Jesuit priests when they, like all members of the order, were expelled from the Spanish empire in 1767. When the black robes failed to return, the bells began their sad, intermittent ringing.

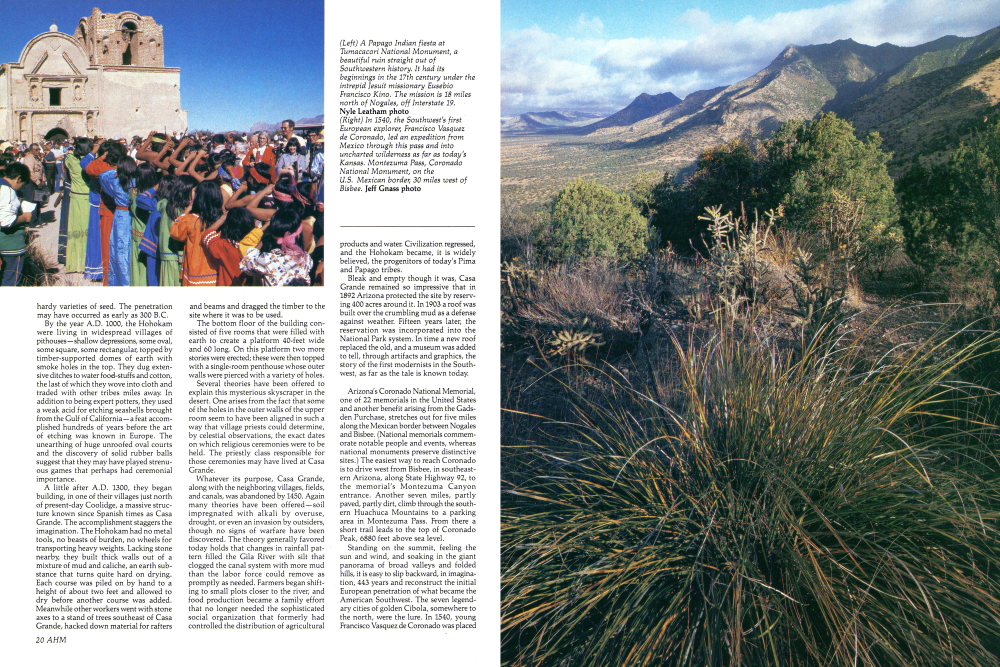

A flawed tale, obviously. In 1767, Tumacacori (Too-mah-COCK-oh-ree) was a visita (a temporary mission station with no resident missionary) and served only irregularly by the priests stationed at Guevavi, 15 miles to the south, and it is doubtful that its small, flat-roofed adobe church possessed bells of the kind implied in the story. Still, legends often capture fundamental truths: Tumacacori's story does tell of the sadness of lost aspirations. The famed Jesuit missionary, Eusebio Francisco Kino, discovered the site in 1691-a ranchería, or brush-hut village, of Pima Indians on the east side of the meandering Santa Cruz. Within another 10 years, he and his associates had introduced grain and livestock and had launched programs designed to teach the Indians civilized customs and Christian faith. Misunderstandings arose in time; resentments festered. In 1751, Indian revolts spread from the south into the Santa Cruz Valley. The missions were abandoned, and the Jesuits did not return until 1753, when a presidio (military garrison) was established at Tubac, about five miles north of Tumacacori. This time they settled with their Indians on the west side of the river, where they built the small chapel-60 feet long and 20 wide-of the bell legend. In 1767, as noted before, the Jesuits were expelled and replaced by gray-robed Franciscans. It was a rugged inheritance. Apache raids intensified. Guevavi, the erstwhile headquarters of the district, was abandoned; Tumacacori, supposedly protected by the Tubac presidio, became the head mission.

(Left) "... the storm roaming the sky uneasily like a dog looking for a place to sleep in, listen to it growling." Elizabeth Bishop. East of Saguaro National Monument. Peter Kresan photo (Below) "Come to the sunset tree! The day is past and gone." "Tyrolese Evening Song" - Felicia Dorothea Hemans. Manley photo In 1800, encouraged by a peace treaty with the Apaches-its effects proved temporary - the Franciscans began building a new church. Like the old Jesuit chapel, it faced south, with the tall Santa Rita Mountains looming behind as a picturesque backdrop. Though the magnificent "White Dove of the Desert" at San Xavier del Bac, just south of Tucson, had been chosen as an architectural model, poverty, governmental paralysis in Spain, and renewed Apache troubles forced cutbacks. But a fine white dome did grace the north end of the Tumacacori structure; classical columns and statuary niches enlivened the facade; the interior, softly lighted by high clerestory windows, was impressive; and bordering the building on the east was a commodious quadrangle of living quarters and work areas, protected by a substantial adobe wall.

The accomplishments were soon marred. The priests had to leave when newly independent Mexico expelled all Spaniards who would not take an oath of fealty to the new government. Shortly thereafter all mission property was secularized. For a time, a few Indians stayed at the church, the only home they knew, and kept it in repair, but then Apache harassment grew intolerable, and they left, reverently taking the mission's holy objects to San Xavier for storage.

Still darker times came with the Gadsden Purchase. American miners and cattlemen swept into the area, camped in the mission buildings, and used the walled compound for corralling work stock and parking wagons. The unattended church began crumbling away; its roof and choir loft collapsed.

Tumacacori's spirit persisted, however, and in 1908 the National Park Service (Right) The brilliant yellow of brittle-bush sprouts like sunlight from the rocky soil of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Jerry Sieve photo (Below) Prickly pear cactus perch above Seven Falls in the Santa Catalina Mountains. David Muench photo (Following panel, pages 30-31) When conditions are right at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, a rainbow-hued magic carpet of desert wild flowers appears almost overnight in spring. Bob Clemenz photo It took over, as a National Monument, 10 acres embracing the ruin 10 of the 6000 or more that had made up the old Indian grant. Today partial restoration tells of dreams only partially realized. More can be learned from the artifacts, pictures, and dioramas in the monument's excellent museum, whose aromatic patio and splashing fountain encourage contemplation. But perhaps the best way to sense the meaning of the spot is to regard the massive bell tower, which was never finished, and remember the story of the ghostly bells that never were.

Man-made relics worthy of preservation are only part of what the Gadsden Purchase brought to Arizona. There were also natural wonderlands of rock and bizarre vegetation that in time formed the basis of three more monuments.

Chiricahua National Monument, 10,645 acres, came first, in 1924. Rumpling the western section of the Chiricahua Range in southeastern Arizona, are the fantastic

text continued on page 33

(Left) Organ pipe cactus, a close-up study in line and color. Peter Kresan photo (Bottom) Mamillara Pusilla, one of hundreds of original scientific drawings from William Emory's Report on the United States and Mexican Boundary Survey. text continued from page 28 remnants of volcanic fires congealed into shapes that man's unaided imagination could scarcely have conceived of. Swollen tumors stand balanced on scrawny necks. There are twisted gargoyles. Abyssinian frescoes. Chinese walls creased by erosion into a jumble of hieroglyphics. Walking among them under the brow of the dark mountain, one inevitably recalls the firebrand leaders of the Chiricahua Apaches who, on occasion, holed up here. Cochise, whose hit-and-run strategies forced the building of Fort Bowie a few miles to the north; Geronimo, who led 143 followers on a desperate break from their reservation and for years stood off a large part of the United States Army; and Massai. While he was being deported east with Geronimo's conquered band, he escaped, returned to the rocky Chiricahuas, and carried on a one-man war for survival. His memory lives in high Massai Point with its stunning living view of the monument.

Established in 1937, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument lies some 200 miles west of Chiricahua, along the border. Far larger (330,870 acres) and far more open, it is equally strange. Here, in pastel valleys between gaunt, dorsal-fin mountains and sawtooth hogbacks, is the only spot in the world, outside of northwestern Mexico, where considerable numbers of organ pipe cactus grow. Dense masses of thin, jointed columns branch out at ground level from a single main stem and rise as high as 20 feet. The organ pipe fights drought with a wide network of shallow roots that quickly sucks up whatever moisture falls and passes it on for storage in the pulpy flesh between each column's waxy skin and the flexible woody limbs that support it. Several vertical pleats line each "pipe!" This enables the plant's skin to expand as water is stored and to shrink during drought. Its fragrant yellowish flowers bloom only at night, perhaps another adaptation to heat and dryness. In addition to phalanxes of cactus and other arid-country plants, the monument shelters abandoned mines and cattle ranches. In its southwest corner, close to the Mexican border, is a brackish pond fed by Quitobaquito Springs, one of the few sources of water along the once deadly trail-El Camino del Diablo, (the Devil's Highway)-that led during the last century from the mining centers of Sonora to those in California. Gruesome tales abound, made believable by being set in this last relatively unspoiled, quintessential desert.

Though smaller than Organ Pipe, Saguaro National Monument, established in 1934, is more varied, thanks to somewhat heavier rainfall combined with sharp differences in altitude. The visitor center of the monument's 27-square-mile western (Tucson Mountain) unit lies roughly 12 miles west of Tucson. From a low of 2200 feet, the land climbs to the top of Wasson Peak, 4687 feet in elevation. The eastern (Rincon Mountain) unit, located slightly southeast of Tucson, embraces 99 square miles and rises from 2700 feet to 8666 feet at the summit of Mica Mountain. The thickest stands of the giant saguaro cacti, for which the monument is named, rise like huge bristles out of the bajadas of the Tucson Mountain section. A bajada is a rocky alluvial fan formed by water rushing out of the mouths of adjacent canyons. Drainage from the canyons, added to the drizzly rains of winter and the short crashing downpours of summer, allows the saguaro to fill its accordion-like trunk much as the organ pipe cactus does. And saguaros do not confine themselves to bajadas. They grow among the boulderstrewn hillsides and stand like stiff sentinels on the tops of the ridges. Some grow as high as 50 feet and weigh up to seven tons when full of water. Flowers appear at the tips of the colossal branches late in the spring-four inches in diameter, their yellow centers are surrounded by waxy white petals. Gila woodpeckers and gilded flickers constantly bore nesting holes into the trunks and then move on, leaving the cavities to screech owls, elf owls, and purple martins. As in Organ Pipe, a great variety of cacti thrive in Saguaro-prickly pear, densely needled chollas, swollen barrel cactus. But as altitude changes, so does vegetation, until near the top of Mica Mountain one leaves even the prickly pears and enters the cathedral shade of a ponderosa forest. Different environments attract different forms of wildlife-longtailed, long-hopping kangaroo rats low down, tassel-eared squirrels higher up. But none are stranger than javelinas, or peccaries. Massive headed and slim flanked, they drop to their knees in the bottoms of brushy washes as they root for food with their piglike snouts. They even relish cactus. And the coatimundi, long of nose and long of tail, a relatively recent immigrant from Mexico, it boosts itself into the trees with its powerfully clawed front legs. As Tucson expands, Saguaro's two exotic units are becoming, in effect, federally protected urban parks. Within a few hours' drive east, west, or south there are still more public treasures, a development James Gadsden never expected when he laid $10 million of his country's money on the line. Seldom have there been better bargains.

Already a member? Login ».