The Papagos

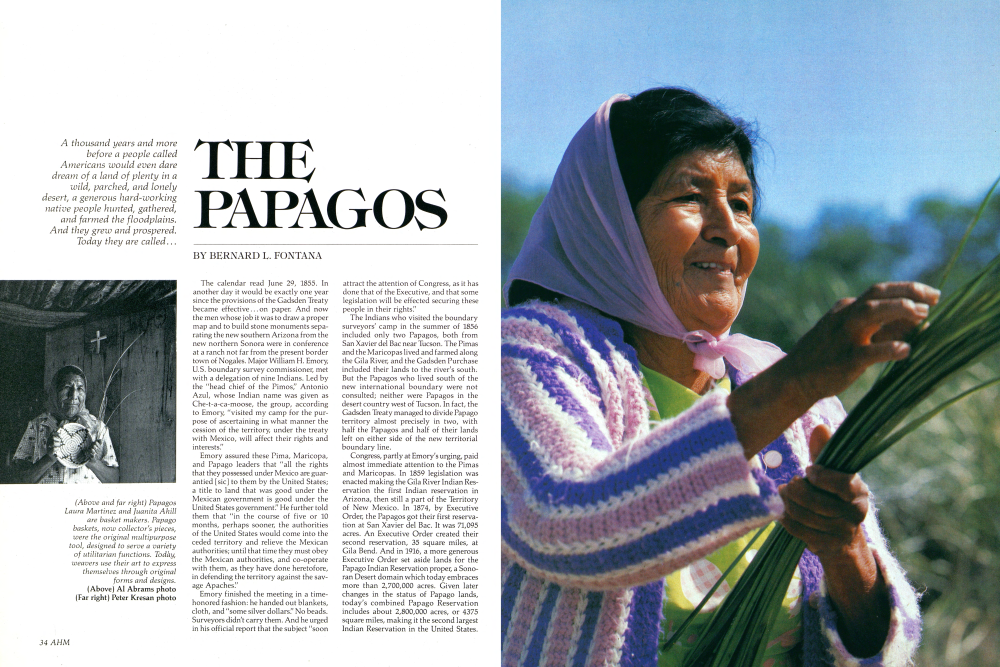

A thousand years and more before a people called Americans would even dare dream of a land of plenty in a wild, parched, and lonely desert, a generous hard-working native people hunted, gathered, and farmed the floodplains. And they grew and prospered. Today they are called...

The calendar read June 29, 1855. In another day it would be exactly one year since the provisions of the Gadsden Treaty became effective...on paper. And now the men whose job it was to draw a proper map and to build stone monuments separating the new southern Arizona from the new northern Sonora were in conference at a ranch not far from the present border town of Nogales. Major William H. Emory, U.S. boundary survey commissioner, met with a delegation of nine Indians. Led by the "head chief of the Pimos," Antonio Azul, whose Indian name was given as Che-t-a-ca-moose, the group, according to Emory, "visited my camp for the purpose of ascertaining in what manner the cession of the territory, under the treaty with Mexico, will affect their rights and interests."

Emory assured these Pima, Maricopa, and Papago leaders that "all the rights that they possessed under Mexico are guarantied [sic] to them by the United States; a title to land that was good under the Mexican government is good under the United States government." He further told them that "in the course of five or 10 months, perhaps sooner, the authorities of the United States would come into the ceded territory and relieve the Mexican authorities; until that time they must obey the Mexican authorities, and co-operate with them, as they have done heretofore, in defending the territory against the savage Apaches!"

Emory finished the meeting in a timehonored fashion: he handed out blankets, cloth, and "some silver dollars!" No beads. Surveyors didn't carry them. And he urged in his official report that the subject "soon attract the attention of Congress, as it has done that of the Executive, and that some legislation will be effected securing these people in their rights!"

The Indians who visited the boundary surveyors' camp in the summer of 1856 included only two Papagos, both from San Xavier del Bac near Tucson. The Pimas and the Maricopas lived and farmed along the Gila River, and the Gadsden Purchase included their lands to the river's south. But the Papagos who lived south of the new international boundary were not consulted; neither were Papagos in the desert country west of Tucson. In fact, the Gadsden Treaty managed to divide Papago territory almost precisely in two, with half the Papagos and half of their lands left on either side of the new territorial boundary line.

Congress, partly at Emory's urging, paid almost immediate attention to the Pimas and Maricopas. In 1859 legislation was enacted making the Gila River Indian Reservation the first Indian reservation in Arizona, then still a part of the Territory of New Mexico. In 1874, by Executive Order, the Papagos got their first reservation at San Xavier del Bac. It was 71,095 acres. An Executive Order created their second reservation, 35 square miles, at Gila Bend. And in 1916, a more generous Executive Order set aside lands for the Papago Indian Reservation proper, a Sonoran Desert domain which today embraces more than 2,700,000 acres. Given later changes in the status of Papago lands, today's combined Papago Reservation includes about 2,800,000 acres, or 4375 square miles, making it the second largest Indian Reservation in the United States.

(Right) Parochial school children pose for a group portrait at the village of Pisinimo, on the Papago Reservation. P.K. Weis photo (Below) The Church of St. Agatha, at Sil Nakya. Every village has a church or chapel, and there are today close to 70 such structures on or near the reservation. Nyle Leatham photo (Bottom) They call themselves O'odham (people); but it means more than that. It also means Those Who Emerged from the Earth. The present Papago population is about 11,000 people, most of whom live in small villages scattered throughout the reservation. Of Earth and Little Rain - The Papago Indians, by Bernard L. Fontana. Nyle Leatham photo

PAPAGOS SOUTHERN ARIZONATHE PAPAGO RESERVATION, MONUMENTS AND MEMORIALS

Papagos also make up most of the population of the Ak Chin Reservation, dating from 1912, but the federal trust lands and various affairs of this community are administered by the Pima Agency at Saca-ton, on the Gila River Reservation. The San Xavier, Gila Bend, and Papago reservations, however, are under the single jurisdiction of the Papago Agency at Sells, Arizona.

For Papagos who continued to live in Sonora after 1854 there was no talk of "reservations." Their status continued simply as that of Mexican citizens. Because they had no deeds or other documents proving they owned their land, they lost most of it to better educated and more aggressive newcomers from the south.

In the mid-19th century, there were perhaps as many as 4000 Papagos in Sonora. By 1894 the majority of Sonoran Papagos had either become Mexicanized or had migrated north of the border. In 1910 the Papago population for Mexico was estimated at 900; in 1943, 505; in 1963, 450; and in 1979, 197, most of them living in Caborca, the largest city in northwestern Sonora. Only at Poso Verde, where an ejido (a grant of communal land) set aside 7675 acres in 1927 for a small Papago community, were Mexican Papagos made secure in their rights to land.If the treaty makers in the United States totally ignored the fact that the new line would divide a people, and even families, subsequent generations of bureaucrats have paid a great deal of attention to Arizona's Papagos.

The first Indian agent was John Walker, a genial Tennessean who arrived to take charge of Indian affairs in the Gadsden Purchase area in the summer of 1857. He immediately issued Papagos free shovels, hoes, brass kettles, butcher knives, scissors, saddlers' awls, needles, axes, steel shovel-plow points, tin cups, and spools of cotton. The American work ethic had come to southern Arizona. And in 1858, when the desert was hit with what Walker considered to be a "drought," he gave away flour to Papagos, all but exhausting the entire supply for the New Mexico super-intendency in the process. It was incon-ceivable to Walker that Papagos could survive on a diet of "mescal [agaves], tunies [prickly pear cactus fruit], and acorns!"

In point of fact, the Papagos of south-western Arizona and northwestern Sonora had been surviving for countless generations on largesse provided by the Sonoran Desert. They hunted its fairly abundant wild game, from rabbits and small rodents to deer and antelope; they gathered from its cornucopia of wild plants, including saguaro fruit, mesquite beans, and sev-eral varieties of greens; and they farmed tepary beans (a native drought-resistant legume), corn, and squash.Papagos who lived along flowing streams like the Santa Cruz and Sonoita rivers (Above) Foreign territory prior to the Mexican War, the bright land south of the Gila is today a mecca for tourists.

Already a member? Login ».