The Unsolved Riddle of the River Hohokam

In July, 1852, United States Boundary Commissioner John R. Bartlett and his party rode horseback from the Pima Indian villages on the Gila River-the southern border of the United States under terms of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo - to look at prehistoric ruins on the lower Salt River. “On our way,” wrote the commissioner, “we saw many traces of ancient irrigating canals, which were the first evidences that the country had been settled and cultivated... We found remains of buildings, all... in shapeless heaps.... On the plain, in every direction, we found an immense amount of broken pottery, metate stones for grinding corn, and an occasional stone axe or hoe. The ground was strewn with broken pottery for miles.” What Bartlett was seeing, as Spaniards and American soldiers and forty-niners had noted ahead of him, were the physical evidences of those who were “all used up,” the Hohokam, in the language of Pimas and Papagos.

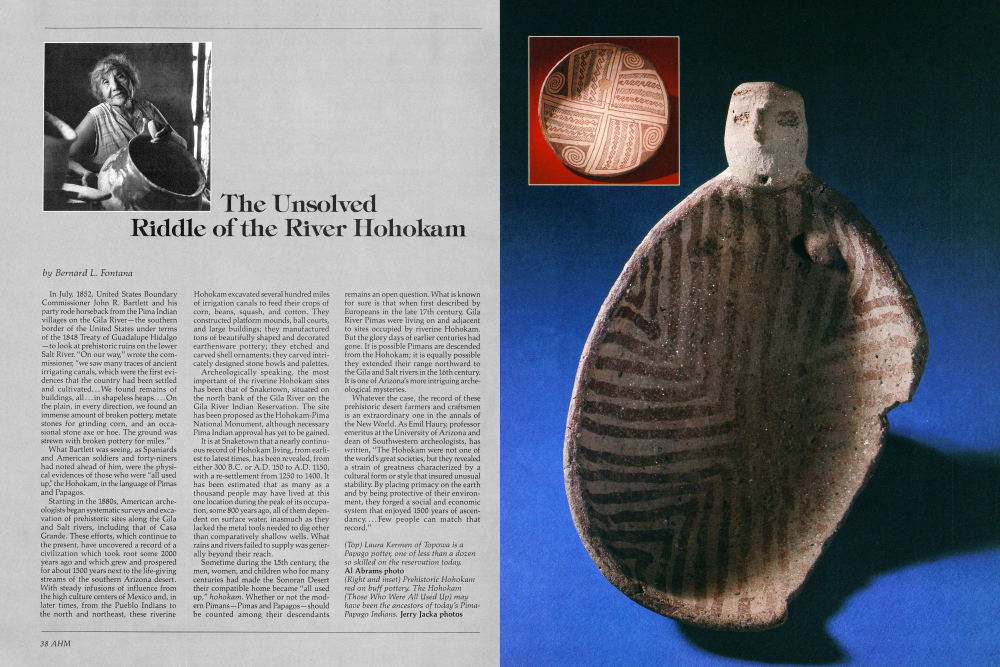

Starting in the 1880s, American archeologists began systematic surveys and excavation of prehistoric sites along the Gila and Salt rivers, including that of Casa Grande. These efforts, which continue to the present, have uncovered a record of a civilization which took root some 2000 years ago and which grew and prospered for about 1500 years next to the life-giving streams of the southern Arizona desert. With steady infusions of influence from the high culture centers of Mexico and, in later times, from the Pueblo Indians to the north and northeast, these riverineHohokam excavated several hundred miles of irrigation canals to feed their crops of corn, beans, squash, and cotton. They constructed platform mounds, ball courts, and large buildings; they manufactured tons of beautifully shaped and decorated earthenware pottery; they etched and carved shell ornaments; they carved intricately designed stone bowls and palettes.

Archeologically speaking, the most important of the riverine Hohokam sites has been that of Snaketown, situated on the north bank of the Gila River on the Gila River Indian Reservation. The site has been proposed as the Hohokam-Pima National Monument, although necessary Pima Indian approval has yet to be gained. It is at Snaketown that a nearly continuous record of Hohokam living, from earliest to latest times, has been revealed, from either 300 B.C. or A.D. 150 to A.D. 1150, with a re-settlement from 1250 to 1400. It has been estimated that as many as a thousand people may have lived at this one location during the peak of its occupation, some 800 years ago, all of them dependent on surface water, inasmuch as they lacked the metal tools needed to dig other than comparatively shallow wells. What rains and rivers failed to supply was generally beyond their reach.

Sometime during the 15th century, the men, women, and children who for many centuries had made the Sonoran Desert their compatible home became “all used up,” hohokam. Whether or not the modern Pimans-Pimas and Papagos-should be counted among their descendants remains an open question. What is known for sure is that when first described by Europeans in the late 17th century, Gila River Pimas were living on and adjacent to sites occupied by riverine Hohokam. But the glory days of earlier centuries had gone. It is possible Pimans are descended from the Hohokam; it is equally possible they extended their range northward to the Gila and Salt rivers in the 16th century. It is one of Arizona's more intriguing archeological mysteries.

Whatever the case, the record of these prehistoric desert farmers and craftsmen is an extraordinary one in the annals of the New World. As Emil Haury, professor emeritus at the University of Arizona and dean of Southwestern archeologists, has written, “The Hohokam were not one of the world's great societies, but they revealed a strain of greatness characterized by a cultural form or style that insured unusual stability. By placing primacy on the earth and by being protective of their environment, they forged a social and economic system that enjoyed 1500 years of ascendancy.... Few people can match that record.”

planted in the floodplains and in places where water could be brought with canals. Those who lived in riverless realms spread the summer's flash flood waters over valley fields by putting brush dams at the mouths of arroyos where these natural ditches emptied their harvests of mountainside rainfall. It was an effective system, one supported further by Papago traditions of generosity and sharing. However unconsciously, Papagos strove to distribute the desert's wealth evenly. When first seen by Jesuit missionaries and Spanish soldiers, in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Papago settlements in the dozens were dotted over about 24,000 square miles. Some of these were hardly more than camps. Others were tiny villages occupied only seasonally, and still others, like Bac on the Santa Cruz Riverwhich Father Eusebio Kino christened San Xavier after his favorite saint-were large and permanent. The biggest villages, those with more than 200 or 300 people, were always situated along the desert's streams.

Today's Papago villages still tend to be small and scattered, but with a few important exceptions. There are now large permanent settlements where formerly there were only small or temporary ones. The biggest of these is Sells, named for Cato Sells, the man who was commissioner of Indian Affairs when the main Papago Reservation was created in 1916. It is the reservation's administrative headquarters, the center of operations for the Papago Agency of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Public Health Service, Indian Oasis School District number 40, and the Papago Tribe of Arizona.

PAPAGOS

The Papago Tribe of Arizona was created in 1937 when Papagos voted to organize themselves under terms of the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act. The constitution and bylaws adopted in 1937 led to the creation of 11 political districts, including San Xavier, Gila Bend, and nine districts on the main reservation. The tribe is governed by an elected chairperson, vice-chairperson, secretary, and treasurer in addition to 22 people who make up the tribal council, two representing each district. Each of the 11 districts has a similar governing body of its own. The model is federalism. In aboriginal times, Papagos relied on their immediate desert surroundings and on one another for all the necessities of life: food, clothing, shelter, and companionship. The energy they spent in all these Arizonans, long involved in cattle raising, came to love rodeo entertainment naturally. And the state's Indians are no exception. At left, a Papago cowboy gears up for a bull ride competition at Topowa. And, below, biting the dust after a tough Brahma bull ride. P.K. Weis photos endeavors was their own. Foot power, hand power, man power, woman power; the sweat of one's own brow; the products of one's own labor. But even before the Gadsden Purchase, changes were made in the equation. Europeans introduced not only forms of a new religion, new speech, new dress, and a new architecture and village plan, but new sources of food and an attendant new economy. The missionaries of New Spain dumped the energy resources of Europe into their newly found Promised Land, scattering among Papagos cattle, horses, sheep, goats, pigs, chickens; wheat (which could be grown in winter), European beans, chick-peas, lentils, quinces, oranges, apricots, peaches, and pecans; cabbage, lettuce, onions, garlic, and leeks; and, for a touch of color, roses and lilies. They introduced the plow and, possibly, ditch irrigation. Few, if any, of these plants and animals are naturally suited to an arid environment, but they became for Papagos, and all of us since, the apple in the Garden of Eden. Once tasted, there has been no turning back.

By 1854 Papagos had familiarized themselves with European products. After the Gadsden Purchase, they became enmeshed in another foreign tradition: cash economy. Barter and exchange gradually gave way, in the second half of the 19th century, to the notion that one could sell one's labor for money and use the money to buy what were becoming the new necessities of life in the desert: coffee, sugar, canned peaches, canned lard, metal tools, wagons, horse trappings, commercially woven cloth, and commercially made clothing. Silver mines, followed soon by copper mines, were developed by Anglo American entrepreneurs in the Papago country, and all of these operations, however shortlived, hired Papagos as laborers. NonIndian ranches that began to prosper in southern Arizona also hired Papago hands; so did the Southern Pacific Railroad, building through the desert in 1878-80. From 1906 to 1908, dozens of Papago men worked in the vicinity of Yuma, Arizona, building levees and ditches in a succesful effort to stem the flow of the Colorado River into the Salton Sea. What all of this added up to was the growth of Papago dependence on outside resources.

In 1983, the destinies of Papagos are very much tied to events in the modern world. There are now more than 11,000 of them living on their three reservations, in such cities as Tucson and Phoenix, and in places at least as far away as Chicago and San Jose. Paved roads have been laid throughout the Papagos' homeland; their children attend public, parochial, and Bureau of Indian Affairs schools on the

text continued on page 44

Already a member? Login ».