Solar Power in the Land of the Papago

By Bernard L. Fontana In Papago ritual speech, the sun is the "Shining Traveler." He is enshrined in Papago song: In the east is the dwelling place of the sun.

On top of this dwelling place the sun comes up and travels over our heads. Below we travel.

In some traditional Papago ceremonies there was a man who carried or wore a representation of the solar orb. And it has been said there were medicine men who claimed to derive their power from the sun. They were able to take its light and throw it into the night. The strange brightness was rumored to be stronger than daylight, enabling the medicine men to see many miles away.

The first time human beings set foot in southern Arizona, some 12,000 or more years ago, the sun was the great pump bringing water to the earth. Its rays lifted evaporated and distilled sea water to the heavens where the vapor gathered into clouds to be wind-driven miles away over the thirsty desert. From water sprang all life. Small wonder that the Papagos turned every ceremonial effort toward "bringing down the clouds;" small wonder they were respectful of a force so powerful as the sun. The sun's energy continues to bring water to the desert people, but today it is used additionally to suck straws lowered into the earth's crust to get at hidden moisture. A land of sunshine is a land of solar power, and in 1978 solar power began to be used on the Papago Indian Reservation to supply the electricity needed to drive water pumps. It was in 1978 that the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, operating out of the Lewis Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, installed a photovoltaic array in the tiny village of Schuchulik (Chickens, also referred to as Gunsight on some maps) just inside the western edge of the reservation. The photovoltaic array consists of 24 solar-cell panels arranged in three long rows resting conspicuously at the village's outskirts. Surrounded by a chain link fence, they have an extraterrestrial quality.

The sun's relentless daily beaming on these panels generates 120-volt direct current that heads into a storehouse filled with meters, graphs, gauges, and a bank of 53 lead-cadmium batteries connected in series. The most important use to which this electricity is put, especially now that the Papago Tribal Utility Authority serves Schuchulik with alternating current, is to run an efficient two-horsepower motor which in turn operates a big beam pump that can deliver 1100 underground gallons of water per hour into the community's water pipes. Who needs gasoline or diesel if the sun can be tapped to pull water from a 243-foot-deep well?

Schuchulik has been touted as "the world's first solar village," and visitors from throughout the world have come to see how the system works and how efficient it is. Members of the 16 Papago households have been uncommonly patient and gracious concerning this unsought for notoriety. Water is one thing; all those strangers are something else.

Not to be outdone, the villagers of Queens Well in the northwestern corner of the Papago Reservation got a solar contrivance in April, 1982. Queens Well is now the sun's well, boasting "the world's largest solar-powered water pump of its kind." Arizona's Representative Morris Udall, who presided over its dedication, called it "the wave of the future!" And even should the water fail to come in waves, Papagos will be pleased if their domestic needs are cared for.The Queens Well solar pump was funded for about $70,000 via a Department of Energy grant to the Indian Health Service's Office of Environmental Health. The total grant, $850,000, is to provide similar solar power to 10 or 11 additional villages, allowing replacement of gasoline engines. The system for the Queens Well pump needs no batteries and is easier to maintain than that at Schuchulik. An electric control box lets the pump run on smaller amounts of sunshine, and the 450-foot-deep hole can supply 5900 gallons of water a day.

The Federal Photovoltaic Utilization Program, established by Congress in 1979, is what has made the Queens Well solar pump a reality. Remote Papago settlements with names like Sil Nakya (Saddle Hangs), Nolic, and Pia Oik (Homely) are targeted to be future beneficiaries. "The significance of this project goes beyond Arizona," says Congressman Udall. "The Solar Energy Research Institute estimates that 20 to 30 percent of the nation's energy needs can be met by renewable resources by the year 2000."

Should this come to pass, the Papagos will have played their part. And after all, there was a time when 10 percent of the Papagos' energy needs were met by renewable resources-with help from the sun, of course.

text continued from page 42 reservation; electricity has been strung to 18 villages. Schools, television, and radio have combined to make English the language of the young people, although most Papagos retain their own speech either as a first, second, or, with Spanish, third language.

Water for the reservation no longer comes from running streams, springs, or summer cloudbursts. It is sucked from wells. Deep wells that depend on electricity or on diesel fuel to run their pumps. Like the water supply elsewhere in the Gadsden Purchase, it is being taken from the ground and consumed much faster than nature replenishes it.

The Papagos' modern economy is one that depends on leasing copper mines, cattle raising, and government, both fed-

PAPAGOS

eral and tribal. Too, they look forward to receiving the money awarded them by the Indian Claims Commission in 1976 for lands and minerals wrongfully taken away through negligence by the United States (including the land on which Tucson now rests), $26 million plus interest, which by July, 1982, had brought the figure to nearly $42 million. A proposal calls for half of the money to be distributed per capita and the other half to go to the Papago Tribe of Arizona.

Cattlemen that they are, Papagos have never encouraged tourism. There are no overnight accommodations for visitors to the reservation, and places to buy gasoline are few and far, between. And by their own choice, districts, except for San Xavier, have continued to make it illegal to buy, sell, or consume alcoholic beverages on the reservation. One should not assume, though, that Papagos are unfriendly. Most Papagos are good-natured and polite. Papago women make more baskets for sale to outsiders than basket makers of any other North American Indian tribe, and Papago coiled baskets, sewn from yucca, beargrass, willow, and devil's claw, are famous throughout the United States for their sturdy beauty and symmetry. In fact, the two preeminent symbols of Papago identity to outsiders are their baskets and the Papagos' harvesting of saguaro fruit. The former persists with few signs of diminishing; the latter lingers on, a pale reflection of its former self.

Life on the reservation for adults tends to be a five-day weekly round of 8:00 to 5:00 jobs, working for the Public Health Service, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, or for the Papago Tribe in one of its many federally-funded programs now becoming increasingly scarce. Weekends are drives to "town" either Tucson, Ajo, or Casa Grande, or trips to "The Gate," in the International Boundary south of San Miguel, where Mexican traders deliver cheese and liquid contraband.

Weekends, like the saint's day of a village, are also occasion for church. For the most part, this means Roman Catholic Church and Franciscan priests, but there are Protestant denominations as well. Every village worthy of the name has its own church, usually a chapel-sized structure built and cared for by the people themselves. Saint's day celebrations and similar religious feasts turn villages into giant cafeterias. And while the chili, tortillas, beans, salads, coffee, and iced tea are being prepared, there are processions in the plazas in front of the churches; there are religious services; and there is social dancing to the sound of polkas and schottisches played by Papago orchestras.

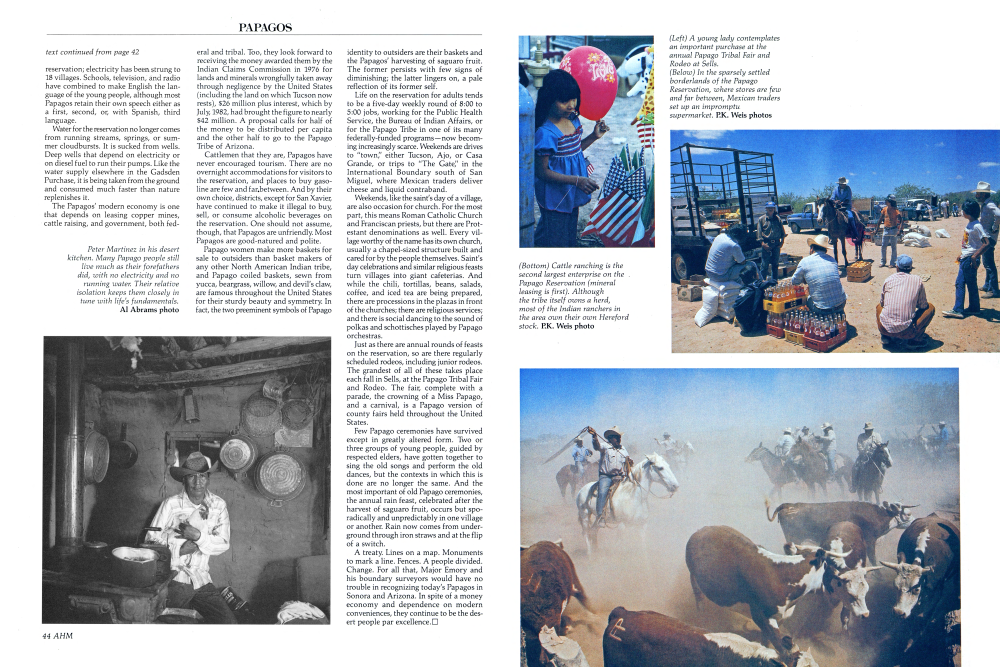

Just as there are annual rounds of feasts on the reservation, so are there regularly scheduled rodeos, including junior rodeos. The grandest of all of these takes place each fall in Sells, at the Papago Tribal Fair and Rodeo. The fair, complete with a parade, the crowning of a Miss Papago, and a carnival, is a Papago version of county fairs held throughout the United States.

Few Papago ceremonies have survived except in greatly altered form. Two or three groups of young people, guided by respected elders, have gotten together to sing the old songs and perform the old dances, but the contexts in which this is done are no longer the same. And the most important of old Papago ceremonies, the annual rain feast, celebrated after the harvest of saguaro fruit, occurs but spo-radically and unpredictably in one village or another. Rain now comes from underground through iron straws and at the flip of a switch.

A treaty. Lines on a map. Monuments to mark a line. Fences. A people divided. Change. For all that, Major Emory and his boundary surveyors would have no trouble in recognizing today's Papagos in Sonora and Arizona. In spite of a money economy and dependence on modern conveniences, they continue to be the desert people par excellence.

(Bottom) Cattle ranching is the second largest enterprise on the Papago Reservation (mineral leasing is first). Although the tribe itself owns a herd, most of the Indian ranchers in the area own their own Hereford stock. P.K. Weis photo (Left) A young lady contemplates an important purchase at the annual Papago Tribal Fair and Rodeo at Sells. (Below) In the sparsely settled borderlands of the Papago Reservation, where stores are few and far between, Mexican traders set up an impromptu supermarket. P.K. Weis photos

Already a member? Login ».