Rescuing Arizona's Endangered Plants

From the wind-whipped scree slopes of the San Francisco Peaks near Flagstaff to the low-level sandbars where the Colorado River trickles into Mexico, a small cadre of concerned people are working to save Arizona's unique but threatened plant life. Ask them what they're doing, and they'll say they're trying to give endangered plants some breathing space, a little more ground to grow on. At the same time, these people themselves are becoming more rooted in their home ground.

Take Rick DeLamater of New River, Arizona, an unabashed lover of succulent plants. "I have a deep appreciation for their ability to adapt to adverse environments," he explained. Rick's tone hints that his sympathy for this other life-form is more profound than people usually care to admit in public. His fascination with exotic succulents led him to faraway lands, then homeward to help conserve plants in his own backyard. A few years ago, Rick took a leave from his work as an Arizona landscaper. He traveled through southern Africa to see aloes, pachypodiums, and other favorite water-storing plants in their Old World habitats. While visiting a botanical research institute in Pretoria, South Africa, he mentioned to scientist David Hardy that he lived in New River, Arizona. "Why, that's near the type locality of the rare Agave arizonica," exclaimed the eminent botanist, as if the fact put both the town and Rick on the map. It was obvious Hardy had seen the beauty of this Arizona century plant in cultivation. He encouraged Rick to find out what was happening with it in its natural habitat. In January, 1983, DeLamater was back in New River, bushwhacking through the dense scrub within 30 miles of his home. It was here he encountered his first example of one of the rarest agaves in the state. The Arizona agave forms diminutive rosettes of dark green leaves with

mahogany margins, hard to spot amidst other dagger-leaved agaves and yuccas in the rugged country where it grows. After more than 75 days' worth of intensive searching, Rick's vision can target the small clonal bunches of Arizona agaves in a sea of other plants. Within the last five years, at least 57 clones of Agave arizonica have been found within two mountain ranges by Rick and botanist Wendy Hodgson, his colleague at the Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix. DeLamater is familiar with every one of them. He has photographs of each plant within the several populations known and can recite the size of each, its exact location, relative maturity, and cause of endangerment. For endangered this plant is. While Arizona agaves were nominated as an official United States endangered species in 1974, they have received so little protection in their habitat that few have been able to reproduce. Cattle devastate a large portion of all century plant flowering stalks that shoot up within the New River Mountains. With these stalks eaten down before they have a chance to flower and set seed, sexual reproduction of this agave is extremely infrequent. Rick and Wendy have had to resort to carrying fencing materials by helicopter and backpack to protect single plants whenever they seem ready for flowering. By collecting pollen from Agave arizonica flowers growing in the Desert Botanical Garden, freezing it, and backpacking it to fenced plants, they have been able to help the plants produce pure seed. Out in the New River Mountains with Rick, I saw his excitement when we verified the seed had matured. But I also observed his disappointment in finding that the majority of the plants trying to develop flowers that season had not been successful. "They munched it," he said sadly, inspecting a gnawed-off flowering stalk. "It waited all these years to flower, but they munched it before it could bloom."

Farmland, and that substituting its liquid wax for whale oil might save certain whales from extinction! You might wonder whether your friend had labored too long beneath the hot Arizona sun.

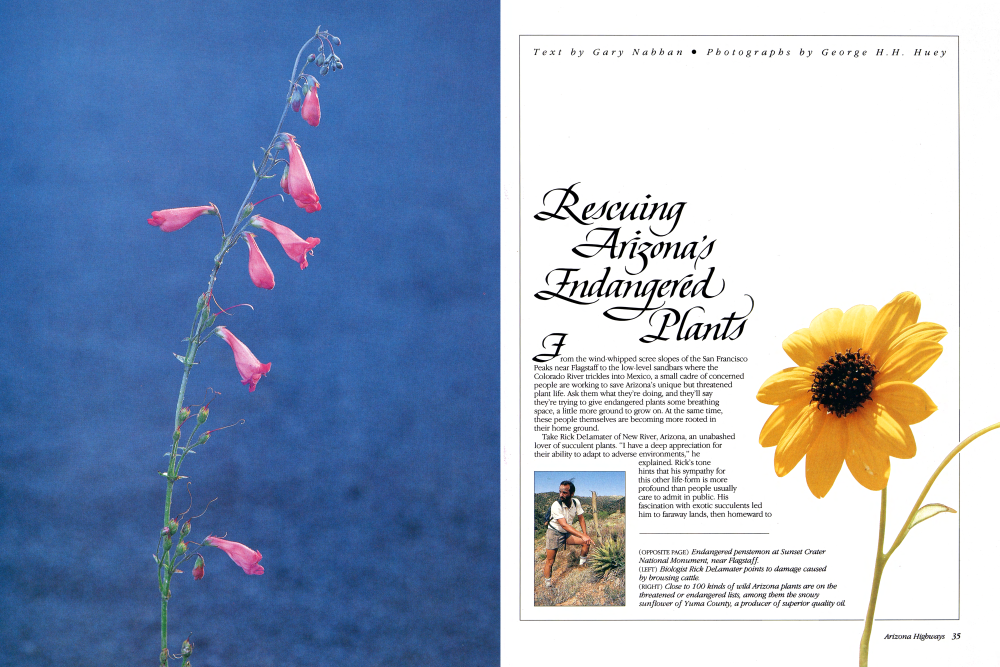

Close to one hundred kinds of wild Arizona plants have been federally recognized as threatened or endangered and candidates for legal protection. Months, sometimes years of surveying these plants in their habitats are necessary before legally listing a plant. Much of this field work has been done by the Arizona Nature Conservancy staff, and by Dr. Barbara Phillips and her colleagues at the Museum of Northern Arizona.

Arizona has one of the most active botanical communities in making such assessments of plants needing protection. "Botanists are currently working on 22 status surveys for candidate species and three new recovery plans for endangered species in Arizona," commented Dr. Peggy Ölwell of the Office of Endangered Species in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Along with Sue Rutman of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Phoenix, Dr. Olwell has reviewed many such reports and action plans with state and federal land managers and with other knowledgeable scientists. The selection of plants for federal listing is a thoroughgoing process with considerable input from conservationists, ranchers, miners, sportsmen, and others.

However, federal designation as a threatened or endangered species only helps protect the plants from obvious imperilment on government-managed lands such as national parks and forests or in areas affected by federally funded development projects.

Arizona was one of the first states to pass its own plant protection laws in 1929, out of concern for "cactus-napping." Then, in 1986, the state began prohibiting the collection of threatened plants in addition to those in demand as ornamentals. But over-collection isn't the only problem, as anyone who has witnessed the devastation of desert lands can see. Mark Dimmitt, curator of plants at Tucson's ArizonaSonora Desert Museum, has repeatedly pointed out that "the real problem with plant protection is habitat destruction" due to grazing, mining, improper use of off-road vehicles, and land development. The state requires a permit if protected plants are to be moved or bulldozed, but it cannot stop all destruction on private lands per se.

Even on federal lands, it has become difficult enough legally to "prove" what factors are endangering a plant. Mary Butterwick, formerly a botanist with the Bureau of Land Management, dedicated hundreds of hours to objectively documenting the pressures exerted on rare plants. She often worked alone, but on one occasion photographer George Huey and I joined her to help with the meticulous measurements she makes on threatened plant growth and reproduction.

"Take a look at this one, George," Mary Butterwick sighed, pointing out a small shrub growing in the whitish cherty clay loam. "That's about as showy as the plants here are going to get!"

Endangered Plants

We hovered around a heavy wire cage that protected a sprawling but smallleafed Arizona cliffrose, Purshia subintegra. This site was the exact place where decades ago Arizona cliffrose was first described as a distinctive species. A resinous evergreen shrub known only from four areas in central Arizona, it has shredded gray and brown bark on its sinuous branches."This individual looks so different from the uncaged plants you'll see over the hill,"

Mary commented. The plants we next walked to were "over the hill" both literally and figuratively. The majority showed signs of heavy browsing: branches broken off or leaves cropped back to a compact woody crown."It looks as if someone gave them a butch haircut," I mumbled, disconcerted.

Since 1984, Mary has been periodically assessing the extent to which this overutilization is truly limiting the species' reproduction and survival. But determining which animal is the culprit is not a simple process. All browsers range soWidely in this desert area that it is difficult to establish which animals are stunting this endangered plant. If cattle or burros are responsible, then a reduction in grazing number or construction of a fence to exclude these animals could be justified. But a fence that would exclude deer as well may be more appropriate.

While answers to this question are being sought, older plants are dying without replacement by new seedlings. Part of the Arizona cliffrose habitat has been lost through roads and right-of-way construction and through mining. This stand of Purshia subintegra is dwindling, despite the fact that the species was Granted legal protection on paper in 1984. If there is a silver lining to the dark cloud, it is that the situation has encouraged the Arboretum at Flagstaff to bring into cultivation cuttings of Arizona cliffrose as well as seeds or shoots of 15 other rare species. Like the rare-species propagation work at the Desert Botanical Garden, the Arboretum's efforts are supported through the recently established Center for Plant Conservation, a national program to provide a horticultural backup to nature reserves.

The talented staff of the Arboretum at Flagstaff is applying its horticultural skills to the conservation of Arizona's special Flora. One of the pet projects is the propagation of a dwarf alpine groundsel, a yellow-flowered perennial tundra plant known only in the San Francisco Peaks. Arboretum workers are sowing seeds of Senecio franciscanus in their beautiful solar and wood-heated greenhouse. Director Wayne Hite hopes that their activities will complement habitat protection efforts of the U.S. Forest Service.

"By saving this one plant in its habitat," noted Barb Phillips, "the whole fragile alpine environment of the Peaks is being preserved. This area of just a few square miles is the only representation of true alpine habitat in the entire state." Controlling off-trail trampling of these plants on the volcanic talus slopes of the Peaks has generated broad support, from the Smithsonian Institution to the Navajo Medicine Men's Association. One hundred miles northeast of the Peaks, another rare plant is being watched by Donna House, a Navajo botanist. She is coordinating the field search for a rare sedge as well as writing the draft recovery plan for this water-loving grasslike plant.

The Navajo sedge, Carex specuicola, is known only from two canyon populations near Navajo National Monument. Donna House has spotted small stands of the sedge within these canyons, where it grows around seeps and in hanging gardens. Donna was the founding botanist of the Navajo Natural Heritage Program, the first plant and animal inventory program of its kind on an Indian reservation in the United States. Developed within the Navajo Nation's Division of Resources with the help of the Nature Conservancy, this program has pioneered the idea of a special natural resources inventory as a service to a Native American community.

"Tribes are becoming concerned about threatened and endangered resources," Donna noted. "This is one reason why our project was developed."

Not only a practicing naturalist-her fieldwork takes her to remote parts of Navajoland-Donna is a cross-cultural educator as well. She must be able to communicate with government agents, academic biologists, herders, and farmers. She does so capably, and her inclusion of Indian knowledge about a rare plant in the federal recovery plan for this species was a "first" in conservation history.

Older members of local Navajo families recall that this sedge, which they call "yellow hay," once provided more food for animals than it does today. They remember, too, that it formerly occurred around springs beyond the little basins to which it is now restricted; it was much more abundant at one time. For the Navajo sedge, scientific studies in the area are so scanty that information of this sort, suggestive of historical environmental change, is most welcome. Navajos will not only be participants in the fact-finding effort about this "yellow hay" but part of the discussion about the sedge's future. It is one of the few endangered plants in Arizona that have been granted "critical habitat" protection by the U.S. government, to protect it indefinitely.

While certain habitats of rare plants can be managed to favor their perpetuity, others still come under the blade of the bulldozer as "progress" marches on. But under such circumstances, there are plant enthusiasts on call to salvage special life-forms legally.

A few years ago, the botanist Frank Reichenbacher discovered a new population of a rare vine in the projected path of the main canal of the Central Arizona Project. Known to scientists as the Tumamoc globe-berry, this seldom-seen vine is a member of the gourd family. Tumamoca macdougalii rises from tuberous roots and can only be found above ground during the short summer rainy season—and only after careful search. Before fall drought and cold weather set in, the vines die back to their belowground water storage tissues, and the plant lies dormant until the following summer. This is now a federally listed endangered species, and although it is not as rare as previously believed, it has been salvaged from the paths of progress intruding upon the Sonoran Desert.

Fortunately, a mix of skills and temper-aments have been found in the people who have taken this plant's plight to heart. Amateur naturalist Clay May and professional botanist Reichenbacher have poured hours of their personal time into learning about the globe-berry's critical limiting factors in the wild. In an unprecedented cooperative venture, the Bureau of Reclamation and the Fish and Wildlife Service relocated hundreds of plants off the canal right-of-way for transplanting to a nearby land reserve established for them. In addition, the National Park Service and the Arizona Nature Conservancy have added their own expertise to round out this conservation program. Finally, as a safeguard, Mark Dimmitt of the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum has taken seeds collected by Reichenbacher and grown a caged globe-berry menagerie of 2,000 plants behind the museum. Funded by the Bureau of Reclamation, this increase of thousands of seeds will serve Finally, as a safeguard, Mark Dimmitt of the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum has taken seeds collected by Reichenbacher and grown a caged globe-berry menagerie of 2,000 plants behind the museum. Funded by the Bureau of Reclamation, this increase of thousands of seeds will serve

Endangered Plants

as a backup should the transplanting attempts with older plants fail.

Thus a plant scarcely known to a handful of botanists in the past is now the subject of a collaborative effort on the part of several agencies and institutions. Knowledge about this red-fruited root succulent has increased a hundredfold just within the last five years.

Tumamoc globe-berry may not yet be a household word, but as a quintessential desert plant, it has what conservationists call "panda appeal"—charm enough to move people to action.

And yet, if it hadn't been for the collaboration of many individuals and agencies, the globe-berry's future would have been very different from what it is today. Perhaps as much as the laws, the management plans, and the regulations written to deal with these precious plants, the care and concern of dedicated individuals are keys to preserving these Arizona resources for future generations.

Gary Nabhan, author of the Burroughs Medal winning Gathering the Desert, is assistant director of the Desert Botanical Garden. His latest book, Enduring Seeds, was recently published by North Point Press.

Tucson photographer George H. H. Huey regularly contributes to Arizona Highways.

Arizona Highways Heritage Cookbook

Step back in history and discover the origins of Southwestern cuisine through this delightful cookbook. From eye-opening appetizers to tempting desserts, Arizona High-ways Heritage Cookbook features more than 200 recipes from the state's Indian, Mexican, pioneer, and cowboy influences. Spiced with historical photographs and anecdotes, it makes a great gift! 176 pages. Hard-cover. $12.95, plus shipping and handling.

Order cookbooks through the attached order card or by writing or visiting Arizona Highways, 2039 W. Lewis Ave., Phoenix, AZ 85009. You can place telephone orders by calling (602) 258-1000 or, toll-free within Arizona, 1 (800) 543-5432.

Already a member? Login ».