Civil War Reenactment: The Blue and Gray at Picacho Pass

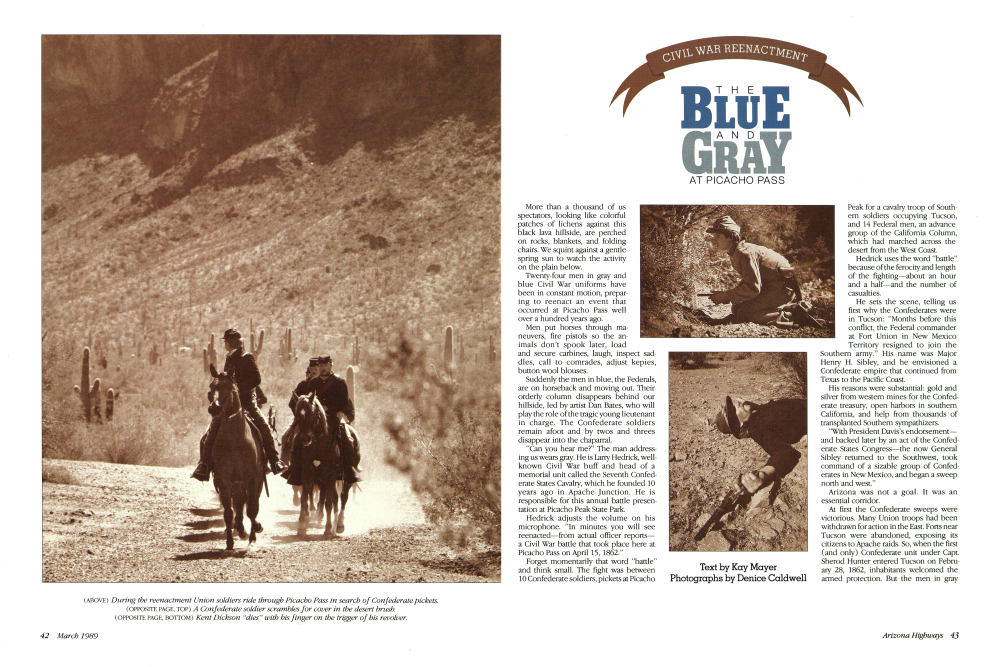

More than a thousand of us spectators, looking like colorful patches of lichens against this black lava hillside, are perched on rocks, blankets, and folding chairs. We squint against a gentle spring sun to watch the activity on the plain below.

Twenty-four men in gray and blue Civil War uniforms have been in constant motion, preparing to reenact an event that occurred at Picacho Pass well over a hundred years ago.

Men put horses through maneuvers, fire pistols so the animals don't spook later, load and secure carbines, laugh, inspect saddles, call to comrades, adjust kepies, button wool blouses.

Suddenly the men in blue, the Federals, are on horseback and moving out. Their orderly column disappears behind our hillside, led by artist Dan Bates, who will play the role of the tragic young lieutenant in charge. The Confederate soldiers remain afoot and by twos and threes disappear into the chaparral.

"Can you hear me?" The man addressing us wears gray. He is Larry Hedrick, well-known Civil War buff and head of a memorial unit called the Seventh Confederate States Cavalry, which he founded 10 years ago in Apache Junction. He is responsible for this annual battle presentation at Picacho Peak State Park.

Hedrick adjusts the volume on his microphone. "In minutes you will see reenacted from actual officer reportsa Civil War battle that took place here at Picacho Pass on April 15, 1862."

Forget momentarily that word "battle" and think small. The fight was between 10 Confederate soldiers, pickets at Picacho

CIVIL WAR REENACTMENT BLUE GRAY AT PICACHO PASS

Peak for a cavalry troop of Southern soldiers occupying Tucson, and 14 Federal men, an advance group of the California Column, which had marched across the desert from the West Coast.

Hedrick uses the word "battle" because of the ferocity and length of the fighting-about an hour and a half-and the number of casualties.

He sets the scene, telling us first why the Confederates were in Tucson: "Months before this conflict, the Federal commander at Fort Union in New Mexico Territory resigned to join the Southern army." His name was Major Henry H. Sibley, and he envisioned a Confederate empire that continued from Texas to the Pacific Coast.

His reasons were substantial: gold and silver from western mines for the Confederate treasury, open harbors in southern California, and help from thousands of transplanted Southern sympathizers.

"With President Davis's endorsementand backed later by an act of the Confederate States Congress-the now General Sibley returned to the Southwest, took command of a sizable group of Confederates in New Mexico, and began a sweep north and west."

Arizona was not a goal. It was an essential corridor.

At first the Confederate sweeps were victorious. Many Union troops had been withdrawn for action in the East. Forts near Tucson were abandoned, exposing its citizens to Apache raids. So, when the first (and only) Confederate unit under Capt. Sherod Hunter entered Tucson on February 28, 1862, inhabitants welcomed the armed protection. But the men in graywere to stay hardly more than two months. Now Hedrick tells us about the Northern force. "Alarmed by the news of the Confederate move west, Union volunteers in California organized to move east in an epic march across the Southwest desert." Elements gathered at the villages of the peaceful Pima Indians, about 45 miles north of Picacho, before moving against Tucson.

Hedrick reads briefly from the Federal officer's report. "On the morning of the 15th, I ordered Lieutenant Barrett to take a detachment of 12 men and Mr. Jones for a guide, and proceed around the Picacha [sic] mountain to cut off the enemy's pickets, if stationed in the Pass."

There were pickets. Hedrick tells us the Confederates who disappeared into the brush represent a group of the tough frontiersmen who occupied Tucson. These 10 men had been assigned as pickets at this rocky peak, 40 miles north. Their mission was to warn Tucson of the approach of the Federals.

The Federal plan was to prevent the warning. Lieutenant Barrett was told not to attack but to await the arrival of the mainUnion force. It was good strategy, but the overeager young lieutenant was spoiling for a fight.

Hedrick sounds a signal. Our eyes search the west as Confederate pickets before us may have failed to do. The crowd murmurs. It has caught sight of the Federal detachment's guidon. The 12 soldiers and civilian scout led by the ill-fated It. James Barrett are advancing rapidly.

In a whirl, firing guns into the air, they surround three Confederate pickets, and we hear the lieutenant demand their surrender. No one is injured.

The Federal scout gallops up, reports enemy hiding in the brush. The hidden Confederates have obviously been alerted by the gunfire, though they are too far away to know their comrades have been taken prisoner.

The disorder of a real battle begins. With more bravery than good sense, and against orders, Lieutenant Barrett charges into the brush, a perfect target on horseback; his men follow, all guns firing.

Four saddles are emptied. The Federals fall back, take time to tie up their horsestime that allows the Confederates toreload. The Federals return on foot, guidon still flying. Shooting resumes, and we see more Federal men fall.

The Federals retreat. The 27-year-old lieutenant and two of his men lie dead, three wounded. The Confederates suffer two wounded, three captured, and do not pursue.

The battle is over. A youngster next to me exclaims, "Boy, that was exciting!" The rest of us agree by applauding. Larry Hedrick announces that we can join the soldiers on the field to ask questions or take pictures.

When the crowd of admirers around Hedrick thins, he tells me no, there is no common background among the men who performed today. It is a volunteer organization, with individual interests in history, horses, black powder weapons, and companionship.

"It is not an elitist group," Hedrick says. "I've been able to cut costs. My wife, Evon, and I learned how to sew the uniforms ourselves, and we rent most of our horses. We do reenactments, and city, governor, and presidential parades. We've also done movies and television, and we do a lot of speaking before school groups."

Virgil Lowell, who has been with Larry for nine years and owns horses, says it's been fun and educational for him, his son, and several other members of his family who also joined. "We talk about what it was like back then," he says, "when a man was challenged all the time. We're trying to keep this history alive."

Rick Dumas also has been with Larry nine years. His heritage is Seminole Indian. "I'm only the second generation out of the Florida swamp." he says and grins. He was attracted to the unit "because they were doing something really interesting outdoors with horses and history." He tells me a Cherokee named Stand Watie was a famous leader with the Confederates, and adds, "The Civil War split Indian families, too."

Before leaving, I meet Dan Bates and receive an invitation to visit his Tucson studio. Bates, I'd been told, carries over his interest in the Civil War into his art. If I am going to learn more about this period in the Southwest, this is one way to do it.

His studio is huge. Cavalry uniforms, saddles, sabres, and other gear cover walls, outfit mannequins, and line glass cases. "I insist on accuracy in my sculptures," Bates explains, gesturing toward his displays. He needs the space, he says, because he works from live models, both humans and animals.

The 37-year-old sculptor, blond and trim, with a luxuriant mustache and a militarily straight back, is as quiet and unassuming here as he was in public. Questions reveal that the family has lived in Arizona more than six decades, with ties back into the 1800s.

"My grandparents had a ranch in the Chiricahuas, where the Apaches had a long history. Johnny Ringo's grave was not far." Stories about Ringo, the Southern-gentleman-turned-murderous-outlaw, and others including Dan's great great-uncle, James A. Cole, a U.S. Cavalry officer were plentiful, and fascinating to a young boy.

Bates learned to ride early and often played cavalry like that "famous uncle who was graduated from West Point." Cole's first post in 1884 was Fort Bayard, New Mexico, and he was later stationed at Fort Apache, Arizona, with the Sixth Cavalry Regiment. His influence continues. Bates says the Cole family gave him sabres, uniforms, and other equipment-"wonderful things" that have been copied in Bates' sculptures.

"By the way, our Sixth U.S. Cavalry Memorial Regiment is normally mounted with the tack, uniforms, and weapons of the 1885 or 1912 period, so there was some variation in dress during our Picacho Pass reenactment."

Speaking of frontier bonding, trooper to trooper and trooper to horse, he points to polychromed action pieces around us in the studio: "Keep the Guidon Flying" and "Mounted Rescue." He then tells the story of a third piece, "Only Cover," in which a trooper is firing his carbine over his horse lying before him.

"This is a good example of the working relationship between men in the West and their horses. This technique was developed to help protect both trooper and horse in situations where there was no place for them to find cover."

Bates sculptures many Western subjects. "But I always come back to the cavalry. I get new ideas with every practice, every reenactment.

"Most important, I come away each time with something"-he searches for the words-"a deeper sense of unity with the men who built this country."

A unity we spectators at Picacho Peak felt, too.

Arizona Highways: "The Westernmost Skirmish of the Civil War," by Bernard L. Fontana, January 1987; "The Confederate Occupation of Tucson," by L. Boyd Finch, January 1989.

WHEN YOU GO... Picacho Peak

Getting there: Picacho Peak State Park is at approximately the halfway point between Phoenix and Tucson on Interstate Route 10.

Attractions: The 3,000-acre park is noted for its colorful spring wildflowers, particularly the Mexican gold poppy, and for desert nature study. Hiking trails encompass the 1,500-foot peak that rises from the desert floor, long a landmark for travelers. Reenactment takes place March 12, 1988, at 2:00 P.M.

Accommodations and services: The park offers 34 campsites with ramadas, picnic tables, and grills. Also available are rest rooms and showers, drinking water, and a playground, plus electronic hookups for recreation vehicles. Restaurants nearby. Rangers on duty. Development and maintenance of facilities for the handicapped is an ongoing program at all Arizona state parks. A leaflet with updated information is available from the Parks Department.

Suggested references: Arizona Highways Presents Desert Wildflowers; Outdoors in Arizona, A Guide to Camping; Travel Arizona; Outdoors in Arizona, A Guide to Hiking and Backpacking: Picacho Pass: Arizona's Civil War Story, by Larry R. Hedrick.

For reenactment information: Seventh Confederate States Cavalry, 10609 Quarterline Rd., Apache Junction, AZ. 85220. Telephone (602) 986-0702.

For more information: Arizona State Parks, 800 W. Washington St., Phoenix, AZ 85007. Telephone (602) 542-4174.

Already a member? Login ».