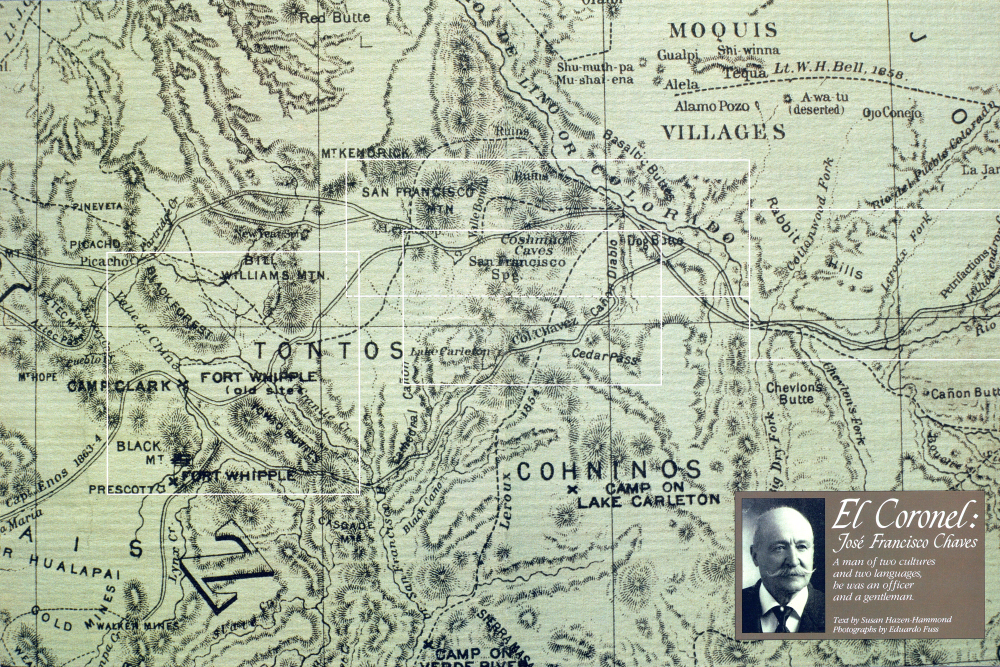

El Coronel: José Francisco Chaves

MOQUIS VILLAGES El Coronel: José Francisco Chaves

A man of two cultures and two languages, he was an officer and a gentleman.

Text by Susan Hazen-Hammond Photographs by Eduardo Fuss

On an icy December day in 1863, Lt. Col. José Francisco Chaves looked out across the sloping prairies and low mesas that lay 2½ days' journey west of Zuni Pueblo and saw what he had been looking for. Before him lay the 600 flat-topped dirt mounds of Navajo Springs. These odd-shaped natural water holes, which collectively resembled a huge prairie dog city, proved that he and the party of politicians his soldiers were escorting had crossed the invisible line that now divided the former New Mexico in two. To the east lay the newly diminished Territory of New Mexico, shrunk to less than half its previous size. Navajo Springs marked the first landmark known to be inside the still unsurveyed eastern boundary of the new, mineral-rich Territory of Arizona, created by an act of Congress earlier that year.

The party under Chaves' attentive watch included a company of Missouri cavalry, a mostly Hispanic detachment of New Mexico cavalry, a handful of California infantrymen, and government officials of the new territory: Governor John N. Goodwin, Secretary Richard C. McCormick, and others. A herd of 500 steers and somewhere between 66 and 100 muledrawn supply wagons also accompanied them. So far that day, December 29, the travelers had ridden only eight miles beyond their last camp, but the news that they had truly reached Arizona brought their day's journey to a halt.

At four o'clock in the afternoon, in the sagebrush and grass-covered prairie adjoining Navajo Springs, this bicultural group celebrated the birth of Arizona with speeches in English and Spanish, a 15-gun salute, and loud cheers. Together they sang the stirring "Battle Cry of Freedom." Governor Goodwin announced a two-fold objective for his government: to protect the lives and property of the citizens of Arizona and to develop the territory's resources "rapidly and successfully." The governor's goals reflected the economic and social conditions of the day. Spurred by rumors of rich gold and silver finds, miners and other settlers were pouring into the territory, invading and claiming land that for centuries had belonged to Arizona's Indians. The Indians were fighting back, and the settlers demanded protection from the government.

For Chaves, 30, a personable native New Mexican known to his men simply as El Coronel, "the Colonel," the creation of Arizona from land that was formerly part of New Mexico meant yet another major

José Francisco Chaves

change in the realities of his world in a lifetime that had already seen many transitions. When he was only five years old, Chaves' wealthy parents, who traced their heritage back to early Spanish colonial settlers, sent José from the family sheep ranch in central New Mexico to the city of Chihuahua to attend school. Then when he was eight, his father, sensing the political and social changes that lay ahead, first brought Chaves home, then enrolled him in school in St. Louis, Missouri, with the admonition, "The heretics are going to overrun all this country. Go and learn their language and come back prepared to defend your people." In 1847 his father's prophecy came true when Col. Stephen Watts Kearny and an army of more than 1,600 American soldiers marched westward from Missouri to wrest

New Mexico from Mexico. Young José Francisco Chaves accompanied Kearny for part of the way, acting as his interpreter. Between that youthful trek in Kearny's company and the winter day in 1863, Chaves studied medicine in New York, drove large flocks of sheep from his family's ranch to California, married a young woman from Canada, served in the territorial legislative assembly, fought with distinction in the Civil War battle of Valverde, and worked with Kit Carson in the complex and morally troubling task of subduing the Navajos and other Indians. During these years, Chaves emerged as one of a new breed of Southwesternersa bilingual, bicultural frontiersman and gentleman, with one foot firmly in each of two worlds: the old realm of Spanish customs and traditions and the new English-speaking world superimposed by the region's annexation and assimilation into the United States.

Now, as commander of Fort Wingate and a senior officer in the First Cavalry, New Mexico Volunteers, Chaves had embarked on a two-part mission. First, he must guide and protect the Goodwin party on the long journey between Santa Fe and Fort Whipple, the new military outpost located at Cienega Creek (today's Del Rio Springs) in Chino Valley in central Arizona. Second, his orders required him to search for a better route from central Arizona back to New Mexico, a route that would bypass the difficult and perilous northern road that led around and beyond the San Francisco Peaks. Following the approximate path of earlier travelers over the centuries, including that of Chaves' own journey in 1854 in the company of trader F. X. Aubry, Chaves and the governor's party left Navajo Springs and rode through the area of present-day Petrified Forest National Park. Here they marveled at the "petrifactions" and filled their bags with souvenirs of petrified wood. Night and day, Chaves and

José Francisco Chaves

His men watched the countryside for signs of Indian warriors. During the first part of January, they encountered none, but many other problems arose. Often the countryside they traveled through lacked the firewood, water, or grazing grass they required. And, in addition to their duties as soldiers, the men had to herd cattle around the clock. Windstorms drove the party to seek cover in an arroyo east of what is now Holbrook. At Lithodendron Creek, Chaves wrote in his daily journal, which later became part of his official report, "the water was very thick and red, and the stock would not drink it, wood and grass very scarce." In the vicinity of modern-day Winslow, where they forded the Colorado Chiquito, as the Little Colorado was then known, they encountered what Chaves called "heavy" roads, soggy from melting snow. Even after crossing the river, they continued to follow it northward in order to avoid Canyon Diablo, which was considered too steep and deep for loaded wagons to cross. Often they had to build their campfires from sagebrush, which "makes a comfortable fire if you only have enough of it," in the words of fellow traveler Judge Joseph Pratt Allyn, who wrote a vivid account of their journey. As they approached the San Francisco Peaks, they passed between volcanic hills on a route Allyn described as "a vast avenue lined with conical hills on either hand." Camped at a water hole near or at the site of today's Turkey Tanks, they inspected the Cosnino Caves, ancient Indian cave dwellings on the north side of the canyon. Years later Capt. Rafael Chacón, an officer under Chaves, reminisced about the heartbreaking living conditions of the Indians they found residing in the caves. "They were so poor that they told me that they sold their children to the Oraibi and Moqui Indians for corn, receiving about one hundred pounds for each child." West of the San Francisco Peaks, the going became much worse. After traveling along what Chaves described as "a very rough and nearly impassable road to the summit or dividing ridge of Bill Williams Mountain" on January 17, Chaves sent out a large advance party under Capt. Chacón to cut tree limbs and remove the boulders from the forested, rocky countryside ahead. Surprised by a party of a hundred whooping Indians, who may have been Tonto Apaches, Chacón and his men fought their way free, killing two attackers. One was so large-6½ feet tall-that a doctor who accompanied the expedition requested and received permission to save the remains for science. Soon a new crisis arose when the party

reached Hell Canyon, where the rough walls that had helped earn the canyon its name appeared impassable for the wagons. After sending every available man out to work on improving the route through the canyon, Chaves ordered that a rope be attached to the back of each wagon. With the wheels locked and 10 men pulling on the rope to slow the wagon's descent, each vehicle slowly crossed the chasm. That day, January 21, the party traveled barely a mile. The exasperated Chaves described Hell Canyon as "the worst...that I ever saw for wagons to cross" and as the equivalent of 40 miles of bad road. The next day, the group easily traveled the remaining 14 miles to Fort Whipple. Here Governor Goodwin set up headquarters temporarily, and for the next couple of months he, Chaves, and other members of the group devoted much of their time to exploring the surrounding countryside. On February 18 Chaves, Goodwin, and a party of soldiers set out in search of a better site for the new territory's capital. A logical location, they believed, would be the valley of the San Francisco River (known today as the Verde). However, after traveling more than 200 miles in and around the river valley, Chaves wrote in discouragement, "During the expedition with His Ex. the Governor, nothing practicable was achieved, we travelled through some of the roughest country that I ever saw." Worried about his mules, which were faring poorly on a diet of nothingbut winter grass, he added, "Harder and rougher work, poor mules were never called upon to perform."

Finally, on April 11, Chaves started back toward New Mexico with the goal of finding a better route to the Colorado Chiquito. Two officers, 35 enlisted men, 15 civilians, and an unspecified number of pack mules and wagons accompanied him. They carried half rations for 30 days. Traveling south to the vicinity of present- day Prescott (where, a few weeks later, Goodwin would locate his capital townsite), they then turned east and spent the night at Woolsey's Ranch; it survives today in stone ruins on private property near the intersection of state routes 69 and 169 in Dewey. The party crossed the Verde in the area of what Chaves called "chalky bluffs" (probably the White Hills), then continued northeast past Stoneman Lakeknown then as Lake Carleton-where they paused for a swim. Subsisting on a low caloric intake and plagued by weakness in their pack mules, the party continued to move slowly eastward until April 23. That day, unable to find water, they followed the rim of a canyon until, as Chaves wrote, "All of a sudden I found myself stopped by the Cañon which turned suddenly to the northwest." This, he concluded, must be Canyon Diablo. It was 200 feet deep, he reported, and of equal width. For about eight miles he and his party traveled along the west rim until they found a site, still not identified with certainty to- day, where they made what Chaves called "a very good crossing."

But still they could find no water. "Both men and mules are already suffering from thirst,' Chaves wrote on April 24. After two weeks of half rations, they must also have been hungry. Eight men hurried off with the empty water kegs mounted on the strongest mules to fetch water for the others from the Colorado Chiquito. On April 30, Chaves and his men finally reached Navajo Springs, where they encountered a supply train and rested briefly. Summarizing the route he had just pioneered, Chaves noted, "It is a good natural mountain road" (his emphasis), which for all its faults was "infinitely better" than the northern route he had followed to Fort Whipple in January. Chaves' superiors, pleased with his explorations, promptly decided to develop the central Arizona cutoff that Chaves had pioneered. In June of that same year, the young lieutenant colonel was sent off from Santa Fe with another party bound for Fort Whipple-which, upon the establishment of Prescott on the banks of Granite Creek, had been moved next door-with orders to retrace his new route, which already was being called "the Chaves Cutoff."

From the Winslow area, the explorer cut southwest on July 15 for about 22 miles and easily reached Canyon Diablo at thepoint he felt he could comfortably cross. But because of the lack of water, lack of time, and worn-out condition of the horses, he decided to save explorations for his return trip and continued on to Fort Whipple by the northern route past the San Francisco Peaks.

Leaving Fort Whipple again on August 5 with 18 days' rations and a couple of wagons, Chaves and his men returned via the route he had taken in April until they were a few miles out from Canyon Diablo. Hoping to find a different point to traverse the canyon, Chaves turned farther north this time, crossing Diablo about 18 miles southwest of the Colorado Chiquito. Sixteen days after leaving Fort Whipple, with only two days' rations to spare, the party reached Fort Wingate in western New Mexico.

In his report on this second expedition, Chaves noted that he believed the new route, once well broken and cleared, would save 80 miles-a good four or five days of traveling. He personally had not saved that many miles, he pointed out, because "the road thus far has not been worked at all, and I have brought the wagons over such places as were perfectly natural and smooth."

Chaves' pioneering explorations focused public attention on the idea of a cutoff from the Winslow

José Francisco Chaves

region to the Verde Valley and beyond. After 1864 many travelers followed such a cutoff, variously designated the Chaves (or Chavez) Cutoff or the Chavez Trail. Soon a pass over which the Chavez Trail climbed, southwest of the future site of Winslow, came to be known as Chavez Pass. However, that route runs south of Canyon Diablo. Ironically, as Professor James Byrkit of Northern Arizona University has pointed out, "J. Francisco Chaves apparently never passed through Chavez Pass."

A careful reading of Chaves' reports suggests that for 1864, at least, Byrkit is right. The question that remains is this: where did Chaves actually go? Some parts of his explorations can be determined fairly closely. For instance, there is little doubt that the lake he described as a "large basin of water in a deep hollow surrounded by ridges" is Stoneman Lake, and lagoons similar to those he reported beyond the lake still exist today. But other points are less certain, for several reasons. To begin with, Chaves kept very brief records. Moreover, both in April and again in the summer, his odometer stopped functioning, requiring him to guess the number of miles he traveled each day. He confessed candidly that he may have overestimated the miles, pointing out, "People generally do when their mules are broken down."

Also, landmarks have changed since

José Francisco Chaves

Chaves' day. For instance, the more than 600 dirt-mound springs that Captain Chacón reported at Navajo Springs have shrunk to a mere handful now, and if you didn't already know you were at Navajo Springs, the discrepancy between their present appearance and the historical record would suggest this wasn't the site Chaves passed at all. Moreover, Chaves may not always have known where he was. Did he really go over Bill Williams Moun-tain, as he claimed? Or did he, as Byrkit believes, travel over Summit Mountain instead? After working extensively with the Chaves material, and after jostling over dozens of back roads with Chaves' reports in hand, I suspect that we may never be able to answer all such questions with complete accuracy.

Chaves' military service as an officer of stature and renown gave him a life full of adventure and challenge. However, he reported that because of his long absences, "I have suffered very heavy losses, and such as have very nearly caused my ruin in a pecuniary point of view." On November 22, 1864, he left the service and re-sumed private life. Nonetheless, for the rest of his days he was still known widely in New Mexico as El Coronel.

During the next 40 years, Chaves had an active, con-troversy-studded career as a politician, businessman, and public servant in New Mexico, attracting many ardent friends and equally ardent enemies. But he never forgot his expe-ditions in Arizona, and he visited the territory whenever he could. Approaching his 70th birthday, he wrote nostalgically to a friend in Indiana in 1903 about "dear old Prescott" and "the hard winter trip to Arizona" in 1863-64.

Aware that his enemies would gladly see him and his associates dead, Chaves sometimes advised his friends never to sit in a lighted room at night in view of an uncurtained window. But on Novem-ber 26, 1904, El Coronel forgot his own advice. As the 71-year-old man sat eating supper in front of a window in Pinos Wells, New Mexico, an assassin's bullet pierced the glass and killed him instantly. The territorial legislature offered a $2,500 reward, but no one was ever convicted.

Although Chaves was one of the best-known citizens of the Southwest for half a century, his memory has faded today.

In New Mexico, writers like Judge Tibo J. Chavez, a distant relative, have published short articles about El Coronel, and New Mexico's Chaves County bears his name, but he has yet to receive the full-length biography he deserves.

In Arizona, Chaves' dual role as the guardian of the gubernatorial party and as an explorer receives little attention in history books now. Moreover, Byrkit has relabeled the old Chavez Trail the Palatkwapi Trail, basing that change on research about other travelers through the centuries. Lake Carleton, renamed Chavez Lake in the last century, has long since worn the newer designation of Stoneman Lake for Gen. George Stoneman.

Still, Chaves' name graces a few Arizona landmarks, including Chavez Pass and Chavez Draw, which today lie on Forest Service Road 69 in the Coconino National Forest. There at Chavez Pass-misnamed or not-the rocky red earth, juniper trees, solitude, and vistas looking north toward the Little Colorado River evoke memories of a few dramatic months in a life full of drama and action.

Selected Reading

Tibo Chavez, "Colonel José Francisco Chavez, 1833-1904, "Rio Grande History, 8: 1978, pp. 6-9.

Pauline Henson, Founding a Wilderness Capital: Prescott, A.T. 1864, Northland Press, Flagstaff, 1965.

John Nicolson, editor, The Arizona of Joseph Pratt Allyn, University of Arizona Press, Tucson, 1974.

Additional bibliographic information is available from the author, Box 8400, Santa Fe, NM 87504.

Photographer-writer team Eduardo Fuss and Susan Hazen-Hammond specialize in topics related to the Spanish-speaking world and the American Southwest.

Already a member? Login ».