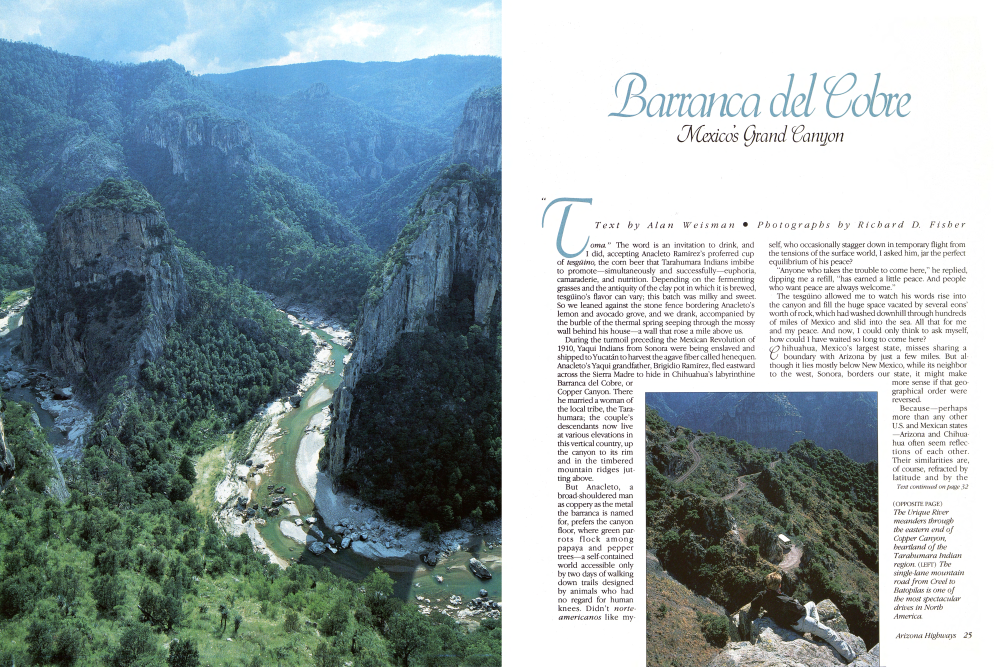

Barranca del Cobre: Mexico's Grand Canyon

Toma." The word is an invitation to drink, and I did, accepting Anacleto Ramírez's proferred cup of tesgüino, the corn beer that Tarahumara Indians imbibe to promote-simultaneously and successfully-euphoria, camaraderie, and nutrition. Depending on the fermenting grasses and the antiquity of the clay pot in which it is brewed, tesgüino's flavor can vary; this batch was milky and sweet. So we leaned against the stone fence bordering Anacleto's lemon and avocado grove, and we drank, accompanied by the burble of the thermal spring seeping through the mossy wall behind his house-a wall that rose a mile above us.

During the turmoil preceding the Mexican Revolution of 1910, Yaqui Indians from Sonora were being enslaved and shipped to Yucatán to harvest the agave fiber called henequen. Anacleto's Yaqui grandfather, Brigidio Ramírez, fled eastward across the Sierra Madre to hide in Chihuahua's labyrinthine Barranca del Cobre, or Copper Canyon. There he married a woman of the local tribe, the Tarahumara; the couple's descendants now live at various elevations in this vertical country, up the canyon to its rim and in the timbered mountain ridges jutting above.

But Anacleto, a broad-shouldered man as coppery as the metal the barranca is named for, prefers the canyon floor, where green parrots flock among papaya and pepper trees a self-contained world accessible only by two days of walking down trails designed by animals who had no regard for human knees. Didn't norteamericanos like myself, who occasionally stagger down in temporary flight from the tensions of the surface world, I asked him, jar the perfect equilibrium of his peace?

"Anyone who takes the trouble to come here," he replied, dipping me a refill, "has earned a little peace. And people who want peace are always welcome."

The tesgüino allowed me to watch his words rise into the canyon and fill the huge space vacated by several eons' worth of rock, which had washed downhill through hundreds of miles of Mexico and slid into the sea. All that for me and my peace. And now, I could only think to ask myself, how could I have waited so long to come here?

Chihuahua, Mexico's largest state, misses sharing a boundary with Arizona by just a few miles. But although it lies mostly below New Mexico, while its neighbor to the west, Sonora, borders our state, it might make more sense if that geographical order were reversed.

Because-perhaps more than any other U.S. and Mexican states -Arizona and Chihuahua often seem reflections of each other. Their similarities are, of course, refracted by latitude and by the

Overlooking the canyon complex (PRECEDING PANEL, PAGES 26 AND 27), a modern Tarahumara cabin sits near the edge of a chasm cut by an Urique River tributary. (LEFT) Daily train of the Ferrocarril Chihuahua al Pacífico passes a waterfall. (BELOW, LEFT) Hikers need a raft to cross the deep pools in the Urique River. (BELOW) Satevo Valley, "the place of sand" in the Tarahumara language. Circumstances of the origin of the mission churchbuilt of fired brick, not adobe-are unknown, a strange mystery of the Sierra Madre. (RIGHT) Visitors often bire Indian guides to lead expeditions into the barrancas. (FOLLOWING PANEL, PAGES 30 AND 31) The 806-foot Basaseachic Falls, north of Copper Canyon in the Sierra Madre, is the highest waterfall in Mexico and fourth highest on the North American continent.

Continued from page 25multiple distortions imposed by an international boundary that separates not just two countries but the developed and the developing worlds. The result is that an Arizonan traveling through Chihuahua (a journey which, thanks to one of the world's most extraordinary railroads, many are now taking) will experience a series of double takes. So much looks so familiar-but, then again, so distinctive.

To the uninitiated, both those names, Chihuahua and Arizona, evoke images of unrelenting desert; actually, each state contains huge expanses of pine-oak woodlands which, during winter, lie deep in snow. But the thick forests of the Chihuahuan Sierra Madre seem filled with extra trees: crowding into the same ecological niche alongside Arizona's classic ponderosa pines are several similar-but-not-matching species, such as the Chihuahuan pines, with needles so long they droop like baby willows.

And the oaks: here Chihuahua gets truly extravagant, with at least 20 cohabiting varieties whose leaves range from pointed slivers to half-moons to conventionally lobed specimens that turn out to be covered with velvet. Each spring, rail passengers in the observation decks of the Ferrocarril Chihuahua al Pacífico get an unexpected bonus, witnessing how Mexico's evergreen oaks trump New England's much-vaunted autumn foliage, turning lemony, golden, crimson, and maroon as their leaves mark winter's end by succumbing to burgeoning new growth.

But more than the deserts or forests or the two states' historical preoccupations with cowpunching and mining-or the fact that each has a famed Indian ruin of similar name (Casa Grande, Casas Grandes)-what elicit constant, heated comparison of Arizona and Chihuahua are their canyons. Within 600 miles of each other exist two of the biggest, deepest, most intricate gorges on earth. The fact that their evolution and composition are substantially different does not detract from the sense they equally impart to their surroundings: that these places, Arizona and Chihuahua, are exalted and special.

At Divisadero, where the train pauses for the first scenic overlook, the Barranca del Cobre is a brooding volcanic version of the bright sandstone theme of Arizona's Grand Canyon. Twenty-five million years ago, northwestern Mexico literally exploded, and virtually every catastrophic geological term-upthrust, overthrust, faulting, folding, tilting, intrusion, extrusion-can be applied to the fractured results. On top of all this fell thousands of feet of airborne ash, which eventually metamorphosed into layers of powdery gray tuff.

Then, to the west, the Pacific and North American continental plates pulled apart; Baja California broke away from mainland Mexico, forming a trench that became the Sea of Cortez, and the water that drained toward it rapidly eroded the tuff plateaus. Streams percolating through crevices on the western slope of today's Sierra Madre Occidental widened into the Río Urique, Río Batopilas, and Río Verde, excavating vast amounts of volcanic debris and leaving behind four barrancas for awed Europeans to discover and name: Cobre, Urique, Batopilas, and Sinforosa. The Spaniards guessed correctly that such rigorous rock-slicing had laid bare inviting layers of valuable minerals. Three

hundred years before John Wesley Powell first saw Arizona's Grand Canyon from river level, Jesuits and miners were conceiving ingenious embryonic technologies to chop, pulverize, and melt copper, silver, lead, zinc, and gold out of the Chihuahuan canyons' depths. But they were not the first ones there: their aqueducts and turbines were preceded by paths in the tuff rimrock above Copper Canyon, scored by several millennia of footfalls of the human race's most highly evolved pedestrians. Backpackers descending these precipitous trails, shod with sturdy hiking boots and bearing an embarrassing wealth of nylon camping gear, return amazed and chastened from encounters on the trail with Tarahumara Indians carrying entire haystacks of corn fodder lashed to their shoulders, wearing only loincloths and single-thong sandals and running. The colonizing Spaniards depended on the Tarahumaras' inexhaustible prowess (their true name, Rarámuri, means "foot runner") to deliver the mail across the barrancas and over the Sierra Madre; single couriers were known to make the 300A mile round-trip between the vicinity of the present rail line and Chihuahua City in five days. Even today, Tarahumara recreation involves leisurely games of kickball over courses that can stretch 50 miles. But the mail run has been cut to a matter of mere hours by engineering that seems mirac ulous-both for the task it performs and for the splendor it reveals to humans who have to do no more than relax and enjoy the view. My Copper Canyon sojourn had begun when friends and I rode a Transportes Norte de Sonora bus south from Nogales, on the border, for 12 reasonably comfortable hours. Much of that time was spent traversing farmland that supplies more than half of the United States' winter vegetables. Now a taxi was depositing us at the San Blas station outside Los Mochis, Sinaloa, for the 6:00 A.M. departure of the Ferrocarril Chihuahua al Pacífico. The diesel-electric-powered trip to Creel, where canyon expeditions usually begin, would take eight hours, climbing 7,000 feet and passing over or through most of the 36 bridges and 87

Barranca del Cobre

tunnels between the coast and Chihuahua City that have made this journey as celebrated as its destination. Depending on peso fluctuations, first class to Creel runs around $12.00 U.S., an amazing bargain for traveling a route whose construction was so complicated and costly that it wasn't finished until 1962, 87 years after it began. The original idea was a route that would connect the American Midwest to a Pacific port 400 miles closer than San Francisco. In 1875 Albert Kimsey Owen of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad traveled, mostly by horseback, from Kansas City to Topolobampo, a small natural harbor near Los Mochis, and pronounced the plan feasible. Major political and financial support came from Enrique Creel, son of the American consul in Chihuahua City. The younger Creel had married the daughter of Chihuahuan Luis Terrazas, who during the 1890s was the single biggest landholder in the world. Before the Mexican Revolution disrupted such cozy dynasties, Enrique Creel became governor of Chihuahua, advisor to the Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz, ambassador to the United

States and vice president of the Chihuahua al Pacífico railroad.

The Revolution, two world wars, and several bankruptcies slowed construction progress, but a combination of postwar vigor and the extraordinary stamina of Tarahumara laborers finally completed the sections between Creel and the Río Chínipas, where the train leaves the coastal plain and promptly enters a tunnel more than a mile long. After that it dances uphill, following a track that loops back upon itself ever higher through side canyons and over waterfalls, where elaborate root systems of white tescalama fig trees cling like dripping wax to cliffsides and red-barked madrones mingle with wild mangoes.

It was at this point in our own trip that we forsook the comfortable overstuffed chairs, where drinks were served to us on cloth-covered tables, to join touring Japanese and German bird-watchers who were standing between coaches, gasping at the sight of elegant trogons and magpie jays with two-foot-long tail feathers.

As the terrain became increasingly alpine, the foliage changed, but neither the complexity of the route nor the sustained beauty around us diminished.

Many take this ride just to sightsee, disembarking for 20 minutes at Divisadero, the barranca's equivalent of Grand Canyon Village, to take snapshots of the vista and buy trinkets manufactured in Guadalajara from picturesque Tarahumara vendors. Nearby are three well-appointed lodges, including one, the Mansión Tarahumara, that unaccountably replicates a German castle.

Lulled by the pleasures of smooth travel on the rails, barely resisting the encroaching inertia that was making such accommodations seem a viable option to what we'd planned, we continued up the line. Two hours later we arrived at the lumber and mission town-consisting of single story log and tuff-block cabins-named for Enrique Creel, the half-American who profited so richly from the labor and resources of the Sierra and canyon people.

Then we walked for days, first over mountains where Indians grow corn on fields so steeply sloped that people have been known to injure themselves falling from furrows. We continued into canyons deeper than any I'd known. Even so, we found people there, as in the tiny pueblito of Guacaybo, built on ledges halfway up the south face of Copper Canyon.

In Guacaybo, cousins of Anacleto Ramírez fed us a dinner of handmade tortillas, refried beans, fresh chiles, noodle soup, goat cheese, oranges, and coffee, charging us 50 cents apiece. For two dollars more, we learned, we could hire the town band-a guitar-accordion duoand have a dance that night. So we did. From their earthen and log homes, the people of Guacaybo emerged, carrying pitch-pine torches, bringing shy daughters with long braided hair to dance with the guests under the stars, on the cracking concrete patio that served for a village square. Burros were braying, nearly in cadence with the corrido music, and new snow gleamed with moonrise on the rim far above us. At one point, I turned to a shrewd old Ramírez uncle named Francisco.

"I could stay here," I told him.

He warmed his tough brown hands over a fire built from oak logs that a Tarahumara had carried in earlier. "Fine," he said. "Marry my grandniece, haul my flour sacks and loads of ore."

The next day, he and I and my com-

WHEN YOU GO...

panions walked together over the rim to the village of Samachique, where we stayed in a snug adobe house belonging to his widowed sister. The following morning, we bade him goodbye and caught a microbus, bumping over logging roads for a day to the colonial town of Batopilas, where showers equipped with wood-fueled water heaters awaited us.

Getting there: Many travelers fly to Los Mochis from Tucson on AeroMexico. Flights leave daily at 1:20 P.M. and arrive at 3:55 P.M. One-way fare is $82 U.S., round-trip $144. Two bus lines, Transportes Norte de Sonora and Tres Estrellas de Oro, leave for Los Mochis from Nogales, Sonora, on a regular schedule throughout the day. The fare is about $10; meals can be purchased inexpensively during frequent stops en route. The trip takes about 12 hours. To obtain a tourist card at Mexican Customs at the border, U.S. citizens must present a birth certificate, passport, or valid voter's registration. And if you plan to drive, you must obtain Mexican auto insurance and a car permit. Those who drive to Los Mochis can arrange to leave their cars at the Hotel Santa Anita, Box 159, Los Mochis, Sinaloa, Mexico; telephone (681) 5-70-46. (The Santa Anita also provides accommodations and has an in-house travel agency. Other economical hotels are the Americana and the Fénix, both near the bus station.) For $2.50, the Santa Anita provides a shuttle to the train station; guests meet in the lobby at 5:00 A.M. Taxis are also available but should be engaged the night before the train departure.

Train reservations are recommended; the hotel will make arrangements on request. For those who can afford to pay about $1,850 a person, Rail Passenger Services, Inc., Box 26381, Tucson, AZ 85726, telephone (602) 747-0346, provides deluxe eight-day, seven-night service from Tucson. Its Sierra Madre Express consists of four private cars, which have been rebuilt, carpeted, outfitted with original fixtures, and equipped with a kitchen. It connects with the Ferrocarril Chihuahua al Pacífico at Los Mochis. Tours are arranged and included in the fare.

Where to stay: Hotel facilities and rates cover a wide range, from less than $15 (single) to more than $115 (double) a night, depending on the season, the nature of the establishment, and the exchange rate. The Posada Barrancas and the castellated Mansión Tarahumara are near the Barrancas station a few miles before Divisadero, and the Hotel Cabañas Divisadero is in the town. The Hotel Misión in the village of Cerocahui, reached by a shuttle service "You did not stay in the barranca," Francisco Ramírez had noted as weembraced and parted. But of course I knew that—and every day since, back to the mere surface of things, I have known it all the more.

Barranca del Cobre

From the Bahuachivo station south of Divisadero, provides excursions to Urique Canyon. A small, un-named but easy-to-find hotel in Cerocahui rents rooms without baths for a fraction of the Misión's price. Side trips to the Barranca de Urique and to a nearby waterfall can be arranged. At Creel you can stay in the Hotel Parador de la Montaña, the Hotel Nuevo, or the Casa de Huéspedes Margarita. The Hotel Bertis provides adequate accommodations, and Copper Canyon Lodge, about 15 miles south of Creel, is rustic but elegant. Stop at the Tarahumara Mission Store next to the railroad track for information, guidebooks, and souvenirs.

You can arrange transportation to Batopilas in a hotel van; the trip will take about six hours. Or you may ride the crowded public buses (sometimes standingroom only); they leave early several mornings a week and make the journey in eight to ten hours. At Batopilas there are a few inexpensive hotels; Monse Bustillos' pension-style accommodation (about $10 a night) has a Tarahumara curio shop, and Bustillos speaks English.

Backpacking: Topographic maps and guidebooks are available at the Tarahumara Mission Store in Creel, but hikers should acquire such aids before leaving home if possible. Do not attempt to travel in the canyons without them. The trail network is byzantine and in places impossible. Guides can be hired, but rarely for more than a day or so.

The Tarahumaras: Most of these Indians, virtually synonymous with the barrancas, actually live in the highlands above. They are polite but shy, retiring, and often seen only from a distance. Many do not speak Spanish. An excellent time to see both Tarahumaras and the countryside is at Easter, when rural Indians come to the villages for elaborate Holy Week ceremonies.

Warning: This is not recommended four-wheel-drive country. Stay near the train or in the canyons. Poppy growers in the Sierra Madre unfortunately mean business.

For further information, contact: Sunracer Travel Group, Box 40092, Tucson, AZ 85717, telephone (602) 881-0243; Fiesta Tours, 4809 De La Canoa, Amado, AZ 85645, telephone (602) 398-9705.

Already a member? Login ».