Legends of the Lost

Legends of the Lost A Gold Hoard Hidden in Colossal Cave May Be Phony, but the Tale Charms Visitors

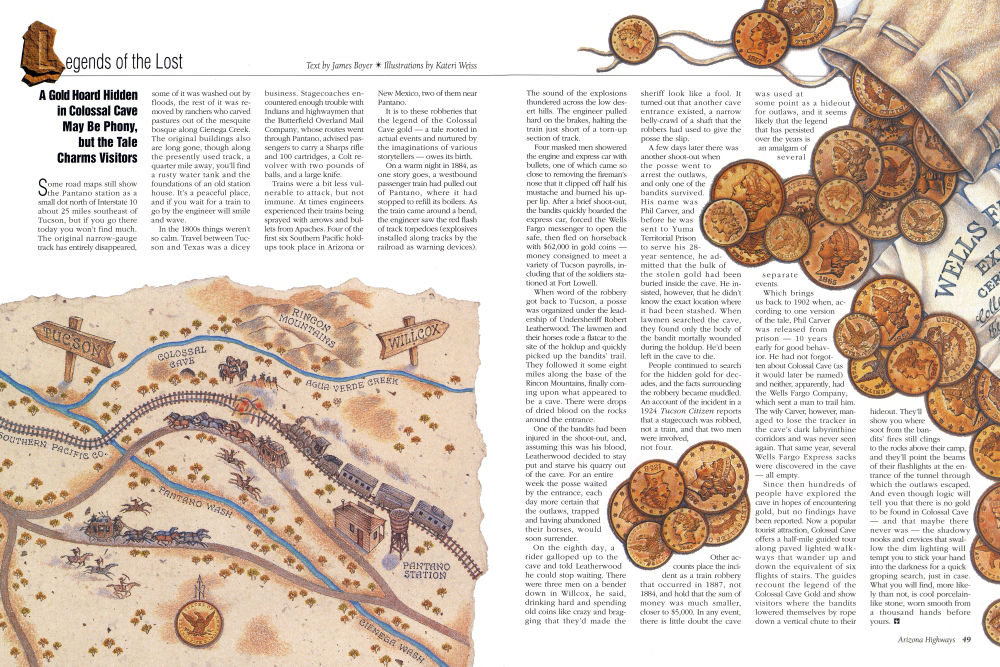

Some road maps still show the Pantano station as a small dot north of Interstate 10 about 25 miles southeast of Tucson, but if you go there today you won't find much. The original narrow-gauge track has entirely disappeared,some of it was washed out by floods, the rest of it was re-moved by ranchers who carved pastures out of the mesquite bosque along Cienega Creek. The original buildings also are long gone, though along the presently used track, a quarter mile away, you'll find a rusty water tank and the foundations of an old station house. It's a peaceful place, and if you wait for a train to go by the engineer will smile and wave.

In the 1800s things weren't so calm. Travel between Tuc-son and Texas was a diceybusiness. Stagecoaches en-countered enough trouble with Indians and highwaymen that the Butterfield Overland Mail Company, whose routes went through Pantano, advised pas-sengers to carry a Sharps rifle and 100 cartridges, a Colt re-volver with two pounds of balls, and a large knife.

Trains were a bit less vulnerable to attack, but not immune. At times engineers experienced their trains being sprayed with arrows and bullets from Apaches. Four of the first six Southern Pacific holdups took place in Arizona orNew Mexico, two of them near Pantano.

It is to these robberies that the legend of the Colossal Cave golda tale rooted in actual events and nurtured by the imaginations of various storytellers owes its birth.

On a warm night in 1884, as one story goes, a westbound passenger train had pulled out of Pantano, where it had stopped to refill its boilers. As the train came around a bend, the engineer saw the red flash of track torpedoes (explosives installed along tracks by the railroad as warning devices).

The sound of the explosions thundered across the low desert hills. The engineer pulled hard on the brakes, halting the train just short of a torn-up section of track.

Four masked men showered the engine and express car with bullets, one of which came so close to removing the fireman's nose that it clipped off half his mustache and burned his upper lip. After a brief shootout, the bandits quickly boarded the express car, forced the Wells Fargo messenger to open the safe, then fled on horseback with $62,000 in gold coins money consigned to meet a variety of Tucson payrolls, including that of the soldiers stationed at Fort Lowell.

When word of the robbery got back to Tucson, a posse was organized under the leadership of Undersheriff Robert Leatherwood. The lawmen and their horses rode a flatcar to the site of the holdup and quickly picked up the bandits' trail. They followed it some eight miles along the base of the Rincon Mountains, finally coming upon what appeared to be a cave. There were drops of dried blood on the rocks around the entrance.

One of the bandits had been injured in the shoot-out, and, assuming this was his blood, Leatherwood decided to stay put and starve his quarry out of the cave. For an entire week the posse waited by the entrance, each day more certain that the outlaws, trapped and having abandoned their horses, would soon surrender.

On the eighth day, a rider galloped up to the cave and told Leatherwood he could stop waiting. There were three men on a bender down in Willcox, he said, drinking hard and spending old coins like crazy and bragging that they'd made the sheriff look like a fool. It turned out that another cave entrance existed, a narrow belly-crawl of a shaft that the robbers had used to give the posse the slip.

A few days later there was another shoot-out when the posse went to arrest the outlaws, and only one of the bandits survived. His name was Phil Carver, and before he was sent to Yuma Territorial Prison to serve his 28-year sentence, he admitted that the bulk of the stolen gold had been buried inside the cave. He inResisted, however, that he didn't know the exact location where it had been stashed. When lawmen searched the cave, they found only the body of the bandit mortally wounded during the holdup. He'd been left in the cave to die.

Other accounts place the incident as a train robbery that occurred in 1887, not 1884, and hold that the sum of money was much smaller, closer to $5,000. In any event, there is little doubt the cave was used at some point as a hideout for outlaws, and it seems likely that the legend that has persisted over the years is an amalgam of several separate events.

Which brings us back to 1902 when, according to one version of the tale, Phil Carver was released from prison 10 years early for good behavior. He had not forgotten about Colossal Cave (as it would later be named) and neither, apparently, had the Wells Fargo Company, which sent a man to trail him. The wily Carver, however, managed to lose the tracker in the cave's dark labyrinthine corridors and was never seen again. That same year, several Wells Fargo Express sacks were discovered in the cave all empty.

Since then hundreds of people have explored the cave in hopes of encountering gold, but no findings have been reported. Now a popular tourist attraction, Colossal Cave offers a half-mile guided tour along paved lighted walk-ways that wander up and down the equivalent of six flights of stairs. The guides recount the legend of the Colossal Cave Gold and show visitors where the bandits lowered themselves by rope down a vertical chute to their hideout. They'll show you where soot from the bandits' fires still clings to the rocks above their camp, and they'll point the beams of their flashlights at the entrance of the tunnel through which the outlaws escaped. And even though logic will tell you that there is no gold to be found in Colossal Cave and that maybe there never was the shadowy nooks and crevices that swallow the dim lighting will tempt you to stick your hand into the darkness for a quick groping search, just in case. What you will find, more likely than not, is cool porcelain-like stone, worn smooth from a thousand hands before yours.

Already a member? Login ».