The World of the Borderlands

or centuries travelers have crossed lines along southern Arizona's borderlands. A fairly recent line - in place now for only 140 years - is the actual international borderline between the United States and Mexico. It was set by the Gadsden Purchase in 1854. Other lines are less exact. They define differences in race or ethnicity, language and custom, religion and history. Cross a line and you find differences - or make a difference. Stay long enough on the other side, and the "foreign" language, customs, ceremonies, artistic expressions, and foods become part of your own way of life. In Arizona's border country, where this kind of exchange has been going on for centuries, the result is a rich social broth. We call it border culture.

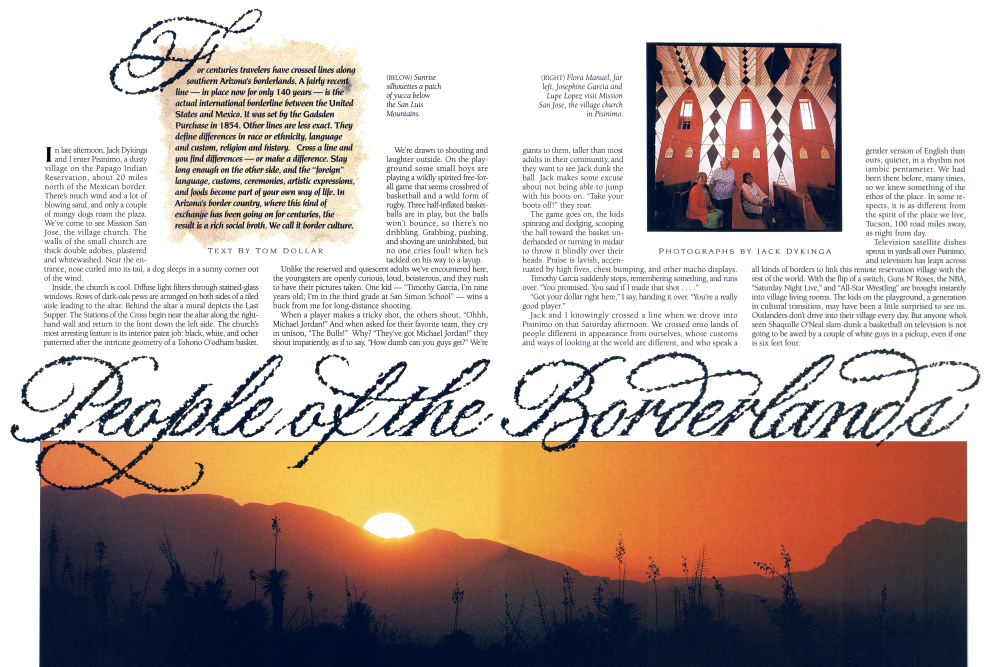

In late afternoon, Jack Dykinga and I enter Pisinimo, a dusty village on the Papago Indian Reservation, about 20 miles north of the Mexican border. There's much wind and a lot of blowing sand, and only a couple of mangy dogs roam the plaza. We've come to see Mission San Jose, the village church. The walls of the small church are thick double adobes, plastered and whitewashed. Near the entrance, nose curled into its tail, a dog sleeps in a sunny corner out of the wind.

Inside, the church is cool. Diffuse light filters through stained-glass windows. Rows of dark-oak pews are arranged on both sides of a tiled aisle leading to the altar. Behind the altar a mural depicts the Last Supper. The Stations of the Cross begin near the altar along the righthand wall and return to the front down the left side. The church's most arresting feature is its interior paint job: black, white, and ocher patterned after the intricate geometry of a Tohono O'odham basket.

We're drawn to shouting and laughter outside. On the playground some small boys are playing a wildly spirited free-forall game that seems crossbred of basketball and a wild form of rugby. Three half-inflated basketballs are in play, but the balls won't bounce, so there's no dribbling. Grabbing, pushing, and shoving are uninhibited, but no one cries foul! when he's tackled on his way to a layup.

Unlike the reserved and quiescent adults we've encountered here, the youngsters are openly curious, loud, boisterous, and they rush to have their pictures taken. One kid - "Timothy Garcia, I'm nine years old; I'm in the third grade at San Simon School" - wins a buck from me for long-distance shooting.

When a player makes a tricky shot, the others shout, "Ohhh, Michael Jordan!" And when asked for their favorite team, they cry in unison, "The Bulls!" Why? "They've got Michael Jordan!" they shout impatiently, as if to say, "How dumb can you guys get?" We'regiants to them, taller than most adults in their community, and they want to see Jack dunk the ball. Jack makes some excuse about not being able to jump with his boots on. "Take your boots off!" they roar. The game goes on, the kids spinning and dodging, scooping the ball toward the basket underhanded or turning in midair to throw it blindly over their heads. Praise is lavish, accentuated by high fives, chest bumping, and other macho displays. Timothy Garcia suddenly stops, remembering something, and runs over. "You promised. You said if I made that shot . . . ."

People of the

"Got your dollar right here," I say, handing it over. "You're a really good player." Jack and I knowingly crossed a line when we drove into Pisinimo on that Saturday afternoon. We crossed onto lands of people different in appearance from ourselves, whose customs and ways of looking at the world are different, and who speak a gentler version of English than ours, quieter, in a rhythm not iambic pentameter. We had been there before, many times, so we knew something of the ethos of the place. In some re-spects, it is as different from the spirit of the place we live, Tucson, 100 road miles away, as night from day. Television satellite dishes sprout in yards all over Pisinimo, and television has leapt across all kinds of borders to link this remote reservation village with the rest of the world. With the flip of a switch, Guns N' Roses, the NBA, "Saturday Night Live," and "All-Star Wrestling" are brought instantly into village living rooms. The kids on the playground, a generation in cultural transition, may have been a little surprised to see us. Outlanders don't drive into their village every day. But anyone who's seen Shaquille O'Neal slam-dunk a basketball on television is not going to be awed by a couple of white guys in a pickup, even if one is six feet four.

gentler version of English than ours, quieter, in a rhythm not iambic pentameter. We had been there before, many times, so we knew something of the ethos of the place. In some respects, it is as different from the spirit of the place we live, Tucson, 100 road miles away, as night from day. Television satellite dishes sprout in yards all over Pisinimo, and television has leapt across all kinds of borders to link this remote reservation village with the rest of the world. With the flip of a switch, Guns N' Roses, the NBA, "Saturday Night Live," and "All-Star Wrestling" are brought instantly into village living rooms. The kids on the playground, a generation in cultural transition, may have been a little surprised to see us. Outlanders don't drive into their village every day. But anyone who's seen Shaquille O'Neal slam-dunk a basketball on television is not going to be awed by a couple of white guys in a pickup, even if one is six feet four.

The gate is closed, chained, and locked, but you can pull apart the closure just enough to squeeze through to the other side. By the looks of things, many have passed here onto U.S. or Mexican soil; the path leading to the gate is well-worn on both sides.

A sign posted on the defunct customs house reads: Lochiel: Effective June 4, 1978. Hours of Service 10 A.M. to 4 P.M. Daily. Lochiel, Arizona. Not long after that sign was posted, the gate was closed for good. Until recently, local people continued crossing at a cattle gate a few strands of barbed wire attached to a post and fastened with a chain loop - just east of the official gate.

It was innocent passage for the most part: U.S. citizens going to Mexico to buy farm produce; Mexicans entering the U.S. for daylabor jobs. Near Patagonia, for example, a man I know built his house with the help of Mexican adobe masons who crossed daily at Lochiel to come to work.

Just up the road from the customs house, a mongrel tethered in a carefully trimmed yard with a neat fence barks incessantly. The dog's noise rouses a man who lives in a house on the Mexican side. He walks to a hole in the fence, 50 yards east of the gate, and enters the U.S. to investigate the cause of the hubbub. His sister owns the house with the dog. She's away, he tells us, so he thought he'd better check us out. He's from Los Angeles, here on vacation. His sister also owns the house on the other side of the fence. He's keeping an eye on both. He parks his car on the U.S. side and walks through a hole in the fence to drive to Patagonia for supplies. Although he hasn't talked to them directly about it, the Border Patrol doesn't seem to mind. "They pretty much know what's going on around here," he says.

Leaving Lochiel and heading up into the Patagonia Mountains, I pass a monument commemorating Fray Marcos de Niza as the first European to enter Arizona. The inscription says the friar passed through here April 12, 1539, on his way to the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola. Appropriately, the marker is a large concrete cross, symbolizing not only the faith of Fray Marcos but also the crosses left behind by Esteban, the black who blazed the trail ahead of the friar.

Up in the Patagonia Mountains, at Washington Camp, I find an old friend, Cucu Granillo. Now 80 years old, Cucu was born at Lochiel shortly after the turn of the century, when the town was called La Noria, "the well."

He has lived in these parts all his life except for duty in World War II, in which he was wounded and disabled for life. His given name is Refugio. He was a mischievous kid. "You know, 'Cucu," he says, whirling an index finger around his ear to explain his nickname.

Washington Camp is a virtual ghost town, but it wasn't always. Back in the 1890s, the Pittsburgh-based Duquesne Mining and Reduction Company bought the Bonanza Mine and set up operations in the town of Duquesne just a mile down the road. Washington Camp was the workers' town, and at one time there were many people here. "Oh, yes," Cucu says, "more than one thousand." And it was a bustling place with a couple of boardinghouses, a school, and a general store owned by the mining company.

Dozens of mines dotted the landscape, and Cucu, who says he worked them all, was called up from the 100-foot shaft of the New York Mine for Army induction in 1944. He can still tick off the mines' names: Black Eagle, Hardshell, Blue Nose, Morning Glory, Endless Chain, Santo Niño, World's Fair, Thunder, Line Boy, Chief, and many others.

Drive into these mountains today, and you'll find only abandoned mine shafts, crumbling remains of former towns, and a few old people, like Cucu, hanging on. He used to add to his disability pension by collecting rocks and minerals and selling them. But a year ago bandidos crossed at night from Mexico, robbed and pistol-whipped Cucu, and left him for dead. Now he is too weak to roam the hills. That episode, he believes, is the reason the Border Patrol secured the gate at Lochiel and posted signs warning against illegal entry.

Paul Noack has the bulging biceps of a blacksmith, a role he sometimes plays as an extra in Western movies shot on location in southern Arizona. “I double in the hard-riding scenes, too,” he says. “Some of these actor fellas don't know their way around horses too much.” Paul knows horses, all right, and a whole lot more about farming and ranching. He had worked five spreads before coming to the Slaughter Ranch down in the southeast corner of Cochise County. “Funny enough, this was the first place that felt like home,” he says. At first he couldn't figure out why.

“I'd be looking at old photos or reading stuff about Texas John Slaughter who settled this place back in the 1890s, and I'd think, I've seen or heard all this somewhere before.” Then one day, Paul, former caretaker at what is formally the San Bernardino Ranch National Historic Landmark, mentioned these déjà vu feelings in a telephone conversation with his grandmother back in Houston. “Bubba,” his grandmother responded, using her pet name for him, “don't you remember that term paper on the Texas Rangers you wrote back in high school? I saved it. It's got two or three pages on John Slaughter. He was a Texas Ranger, you know.” The remote Slaughter Ranch, without electricity until a few years ago, is tucked up against the Arizona-Mexico border fence at the very bottom of southeast Arizona's San Bernardino Valley. To get there, you drive 16 dusty miles east of Douglas on the Geronimo Trail. It's spread-out country down here. The nearest neighbors are a ranch family across the line in Mexico. “Sergio, on the other side, speaks broken English,” Paul says, “and I speak broken Spanish, so we sometimes talk across the fence for an hour or so. Our first year here they came to the fence on our Thanksgiving holiday and invited us over for dinner. The last two years we've met at the fence at Christmas to exchange gifts. It's sort of honor among country friends.” One's a model; the other's pretty enough to be. One's an expert roper, crack shot, and licensed mountain lion hunting guide. The other flies her own airplane and manages a landmark borderlands hotel. Both glow when they talk about border culture as a way of life. They're best friends. “My only thought as a kid was to grow up to be a ranch wife, like my mom, and a hunter, like my dad,” says Kelly Glenn Kimbro. “That's all I thought about. I even rated the boys I dated on how I thought they'd fit into ranch life.” She got her wish. She and her husband, Kerry Kimbro, live on a ranch not far from the Malpai Ranch near Douglas where Kelly grew up. Together with her parents, Warner and Wendy Glenn, she helps run two cattle ranches and leads hunting parties into the nearby mountains. She also models for Sturm Ruger guns and does casting work for the motion-picture industry. “Ranching is not that good a business,” Kelly says. “That's why Dad hunts and why I hunt and do modeling to supplement our incomes, so we can keep living this neat ranch life.” When she makes appearances at gun shows, rodeos, and celebrity roping contests, the striking six-footer is no mere piece of window dressing. She's very good at shooting, hunting, riding, roping, and handling hounds. She was born to it. “I love this border-ranch culture,” Kelly says, her eyes lighting up. “No matter where I've lived, my house has always had cowboy, Spanish, and Indian influences all the way through. In high school, my friends were ranch kids, and my hobbies were always associated with this way of life. I didn't know about anything else - didn't want to know - until I went away to college. “It's a lot of hard work, though,” she allows. “Here's the deal: You get all dressed to go out to dinner and drive by the corral, and a cow is down sick, so you go back up and change clothes and doctor that cow all night. It's your life; you've got to do that first.” Any regrets, I wonder? "Well," Kelly says, pausing. "My only regret is not knowing Spanish. It's a pretty language. I took seven years in school and did not even learn to say adios. Right now I'm reading a book on farm-and-ranch Spanish, and the hired hand, who's from Mexico, is helping me a lot."

Kelly's best friend, Robin Brekhus, has lived along cultural edges all her life, but five years ago when she moved from North Dakota up near the Canadian border to Douglas smack on the Mexican border she wondered if perhaps she'd gone over the edge.

"It was April Fool's Day when I came here to manage the Gadsden," she tells me, "and for the first couple of years I felt like a fool." Robin had arrived with her in-laws, North Dakota wheat farmers and the new owners of the historic Gadsden Hotel. She knew nothing about hotel management; in fact, had stayed in only one or two hotels in her entire life.

"I didn't know the culture, and I was younger than most of the people who worked for me. I'd tell someone to do something, and they wouldn't do it. They didn't like me or respect me and didn't care if I stayed or not."

Robin and I are sitting in the hotel's carpeted El Conquistador dining room. A splendid tile mural celebrates the entrada of the Spanish conquistadores into this territory.

"The hotel had gotten pretty run down," Robin says. "When I arrived, there were not enough dishes to make full place settings."

A waiter in crisp white shirt, dark trousers, and red cummerbund approaches to offer coffee.

"But, you know," Robin continues, "when everyone began to understand that all I wanted to do was make the hotel a nicer place, things got better. And my (LEFT) Robin Brekhus stands on the Gadsden Hotel's marble staircase beneath stained-glass skylights. One of the state's grand old hotels, the Gadsden also features a mezzanine with a 42-foot stained-glass mural.

Spanish, hotel Spanish, that is, which I had to learn because 90 percent of my employees are Mexican, got a lot better."

The Gadsden Hotel, opened in 1907, was destroyed by fire in 1928, and rebuilt in 1929. The splendid centerpiece of the lobby is a sweeping white marble staircase and four solid marble columns with capitals overlaid in 14-carat gold leaf. Vaulted stained-glass skylights soar across the lobby ceiling, and a 42-foot stained-glass mural stretches across the mezzanine.

In its heyday, the Gadsden was a favorite stop for ranchers and businessmen from both sides of the border. Even now the hotel at-tracts as many clients from Mexico as from the U.S. "It's the tallest building in town," says Robin Brekhus. "It's been here since Territorial days. It's a landmark."

What Robin says next surprises me: "I always felt at home in Douglas because it's a lot like North Dakota. I may have moved from border to border, from one culture to another, but the people are the same in both places: good, basic, down-to-earth, hardworking people."

Photo Workshop: Join photographer Randy Prentice on a workshop-tour through the blooming desert to experience Springtime Along the Border, March 23-26. Included will be opportunities to photograph old-world Spanish architecture and a stop at the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. For more information, call the Friends of Arizona Highways Travel Office, (602) 271-5904. For other trips, see page 45.

Tom Dollar lives in southern Arizona because that's his favorite part of the state. This story allowed Jack Dykinga to return to the village of Pisinimo for the first time since the mid-'70s, when he did a special section on the Papago Indian Reservation for Tucson's Arizona Daily Star.

Built in 1907 and rebuilt in 1929 after a fire, the Gadsden Hotel dominates downtown Douglas. At five stories, it's the tallest building in town.

Already a member? Login ».