The Patron Saint of Cabora

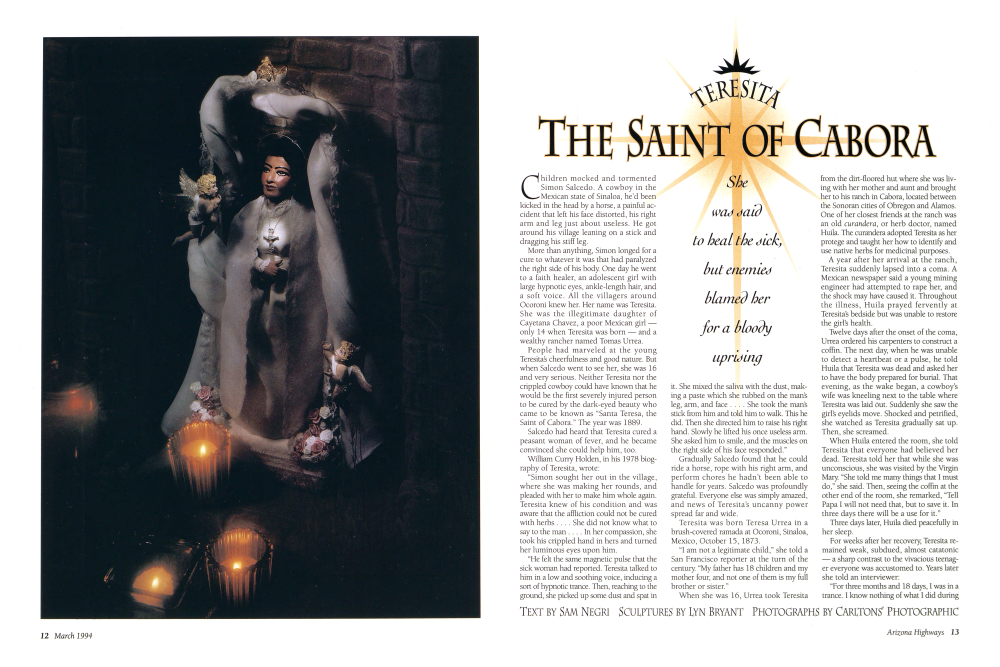

TERESITA THE SAINT OF CABORA

Children mocked and tormented Simon Salcedo. A cowboy in the Mexican state of Sinaloa, he'd been kicked in the head by a horse, a painful accident that left his face distorted, his right arm and leg just about useless. He got around his village leaning on a stick and dragging his stiff leg.

More than anything, Simon longed for a cure to whatever it was that had paralyzed the right side of his body. One day he went to a faith healer, an adolescent girl with large hypnotic eyes, ankle-length hair, and a soft voice. All the villagers around Ocoroni knew her. Her name was Teresita. She was the illegitimate daughter of Cayetana Chavez, a poor Mexican girl only 14 when Teresita was born - and a wealthy rancher named Tomas Urrea.

People had marveled at the young Teresita's cheerfulness and good nature. But when Salcedo went to see her, she was 16 and very serious. Neither Teresita nor the crippled cowboy could have known that he would be the first severely injured person to be cured by the dark-eyed beauty who came to be known as "Santa Teresa, the Saint of Cabora." The year was 1889.

Salcedo had heard that Teresita cured a peasant woman of fever, and he became convinced she could help him, too.

William Curry Holden, in his 1978 biography of Teresita, wrote: "Simon sought her out in the village, where she was making her rounds, and pleaded with her to make him whole again. Teresita knew of his condition and was aware that the affliction could not be cured with herbs She did not know what to say to the man In her compassion, she took his crippled hand in hers and turned her luminous eyes upon him."

"He felt the same magnetic pulse that the sick woman had reported. Teresita talked to him in a low and soothing voice, inducing a sort of hypnotic trance. Then, reaching to the ground, she picked up some dust and spat in She was said to heal the sick, but enemies blamed her for a bloody uprising it. She mixed the saliva with the dust, making a paste which she rubbed on the man's leg, arm, and face.. She took the man's stick from him and told him to walk. This he did. Then she directed him to raise his right hand. Slowly he lifted his once useless arm. She asked him to smile, and the muscles on the right side of his face responded."

Gradually Salcedo found that he could ride a horse, rope with his right arm, and perform chores he hadn't been able to handle for years. Salcedo was profoundly grateful. Everyone else was simply amazed, and news of Teresita's uncanny power spread far and wide.

Teresita was born Teresa Urrea in a brush-covered ramada at Ocoroni, Sinaloa, Mexico, October 15, 1873.

"I am not a legitimate child," she told a San Francisco reporter at the turn of the century. "My father has 18 children and my mother four, and not one of them is my full brother or sister."

When she was 16, Urrea took Teresita from the dirt-floored hut where she was living with her mother and aunt and brought her to his ranch in Cabora, located between the Sonoran cities of Obregon and Alamos. One of her closest friends at the ranch was an old curandera, or herb doctor, named Huila. The curandera adopted Teresita as her protege and taught her how to identify and use native herbs for medicinal purposes.

A year after her arrival at the ranch, Teresita suddenly lapsed into a coma. A Mexican newspaper said a young mining engineer had attempted to rape her, and the shock may have caused it. Throughout the illness, Huila prayed fervently at Teresita's bedside but was unable to restore the girl's health.

Twelve days after the onset of the coma, Urrea ordered his carpenters to construct a coffin. The next day, when he was unable to detect a heartbeat or a pulse, he told Huila that Teresita was dead and asked her to have the body prepared for burial. That evening, as the wake began, a cowboy's wife was kneeling next to the table where Teresita was laid out. Suddenly she saw the girl's eyelids move. Shocked and petrified, she watched as Teresita gradually sat up. Then, she screamed.When Huila entered the room, she told Teresita that everyone had believed her dead. Teresita told her that while she was unconscious, she was visited by the Virgin Mary. "She told me many things that I must do," she said. Then, seeing the coffin at the other end of the room, she remarked, "Tell Papa I will not need that, but to save it. In three days there will be a use for it."

Three days later, Huila died peacefully in her sleep.

For weeks after her recovery, Teresita re-mained weak, subdued, almost catatonic - a sharp contrast to the vivacious teenager everyone was accustomed to. Years later she told an interviewer: "For three months and 18 days, I was in a trance. I know nothing of what I did during

At that time. They told me, those who saw, that I could move about, but they had to feed me; that I talked strange things about God and re-ligion; that people came to me from all the country around, and if they were sick or crip-pled, I put my hands on them, and they got well. Of this, I remember nothing, but when I came to myself I saw they were well."

Tomas Urrea, who was skeptical of the powers others ascribed to his daughter, could not ignore what had happened, and he gradually became convinced there was something unusual about her.

Teresita's reputation as a divinely inspired faith healer spread rapidly in the Mexican states of Sinaloa and Sonora, especially among the Yaqui and Mayo Indians en-gaged in territorial wars with the Mexican government. The Indians adopted Teresita as their patron saint, carried her picture in their packs, and used her name as a battle cry. In the little town of Tomochic, the natives carved a statue of her and put it in their church with the saints.

Mexican officials were not interested in Teresita's ability to heal; they were concerned with her ability to incite the people. Though she never led anyone into battle and said she never encouraged violent confrontations, she was occasionally referred to as Mexico's Joan of Arc. The Mexican government, convinced that she was an inspiration to the warring Indians, saw her as big trouble. In 1892, without a trial, she was exiled to Arizona.

Urrea accompanied his daughter, and the two were placed on a heavily guarded train bound for Nogales, Arizona.

On July 6, 1892, the Mexican consul in Nogales reported to his superiors that large numbers of Indians from Sonora and Arizona were flocking to Teresita's home. Historian Jay J. Wagoner wrote in 1984: "News of Teresa's arrival in Nogales, Arizona, in 1892 spread quickly. A stream of sick and crippled people came from both sides of the border. They had great faith in Teresa's marvelous powers to heal. Busi-nessmen, aware of the profits to be made from visitors, took up a collection to provide a house for the Urreas. Soon Teresa was seeing hundreds of patients. Never did she charge for her services."

For several years, the Urreas moved frequently, partly because revolutionaries from Mexico kept seeking out Teresita to ask for her support in their fight against the dictator Porfirio Diaz. Tomas Urrea was fearful that Diaz's agents might kidnap his daughter and take her back to her homeland a prisoner.

The Indians were still rebelling against Diaz and shouting "Viva Santa Teresa!"

Eventually father and daughter moved to El Paso, Texas, but after several alleged assassination attempts on Teresita, the U.S. State Department suggested it might be best if they moved away from the border. This time, they settled in Clifton, a bustling copper-mining town in the tawny hills along Chase Creek in eastern Arizona. Tomas Urrea launched two businesses there, a wood yard and a dairy. Teresita, meanwhile, continued to see and help the afflicted, many of whom were referred to her by a Clifton physician, Dr. L.A.W. Burtch.

Teresita talked to him in a low and soothing voice, inducing a sort of hypnotic trance. Then, reaching to the ground, she picked up some dust and spat in it.

"I knew Dr. Burtch," said 91-year-old Clifton historian Al Fernandez. "He would send his emotional cases to her. Dr. Burtch was here for years, and he spoke fluent Spanish. He moved away around 1925 or 1930."

As a result of newspaper articles about her healing powers, Teresita was contacted by a "medical company" that agreed to pay her an annual salary to make her talents available across the country. Teresita, who spoke only Spanish, signed a contract with the company but insisted on the provision that she would never have to charge for her services. The contract, however, did not preclude the company from charging. As a result, the sick had to pay at the front door before being admitted to see her in St. Louis and New York, among other places.

After four years on the road, Teresita returned to Clifton, where, at age 32, she died of tuberculosis on January 11, 1906. Today visitors still turn up in Clifton looking for her grave on Shannon Hill. But there is no grave. Shannon Hill is now a barren slag heap encrusted with the hardened residue of smelted copper. "Santa Teresa was buried in the Shannon Hill Cemetery, but that cemetery no longer exists," Fernandez said. "Shannon Hill had a small abandoned cemetery with about six graves in it, but the Shannon Copper Co. built a smelter on Shannon Hill, and then they wanted to build a store, and the only suitable place for the store was the cemetery, so they called the undertaker and exhumed the six graves. Now the smelter and store are gone, and Shannon Hill is just a slag dump."

The Shannon Hill burials were moved to a cemetery in Ward's Canyon in South Clifton, but the original grave sites were so deteriorated that no one knows the identity of those reburied.

"The graves on Shannon Hill had not been kept up, and there were no markers," Fernandez said. "There were only some mounds left there, so the undertakers removed the remains and put them in Ward's Canyon Cemetery and put a wooden cross on each one, but they didn't know who they were.

"People still come looking for information about Santa Teresa," Fernandez added. "Sometimes they want to see where she lived, but the house is gone, too. The house she lived in with her father was an adobe, just behind where PJ's Restaurant now stands, but it was razed many years ago."

Once widely regarded as a humble miracle worker, Teresita is now largely forgotten except as an obscure folk hero whose name occasionally surfaces among historians and anthropologists. With her home and grave destroyed, the secondhand accounts of her achievements form a melancholy epilogue to a life that was unusual and remarkable.

Editor's Note: An all-day celebration honoring Teresita will take place at the restored Old Clifton Southern Pacific Train Depot in Clifton Saturday, April 9, 1994. The Fiesta de la Santa de Cabora will offer a talk by writer-historian Luis Perez along with displays of Teresita photographs and mementos, folk music, food booths, and tours of the historic depot. Posters and postcards featuring Teresita will be available for purchase, and the sculptures featured in this article will be auctioned. To inquire about the auction and for other information, telephone the Greenlee County Chamber of Commerce, (602) 865-3313, or Walter Mares, (602) 865-4966.

Already a member? Login ».