When the Circus Comes to Town

THE ONE AND ONLY CULPEPPER MERRIWEATHER

The saying goes that in addition to bread, there's just one other thing in life that people want most. It rings in my mind as I race west on Ina Road in Tucson, fast enough to catch the attention of a cop in a parked patrol car. It's 6 A.M. on Saturday, and the city's still asleep. I'm sure he's going to stop me and ask why I'm in such a hurry. I decide I'll just point up the road to a rumbling vehicle convoy. "Oh. Well, sure," the cop'll say, seeing what's ahead. "Better hurry so you can catch up."

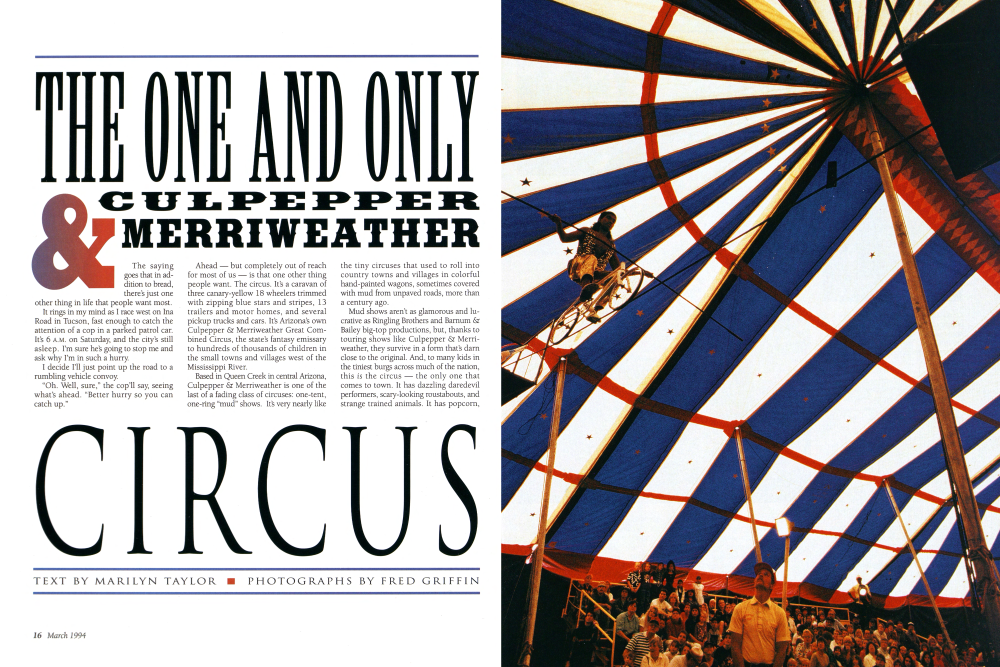

Ahead but completely out of reach for most of us is that one other thing people want. The circus. It's a caravan of three canary-yellow 18 wheelers trimmed with zipping blue stars and stripes, 13 trailers and motor homes, and several pickup trucks and cars. It's Arizona's own Culpepper & Merriweather Great Combined Circus, the state's fantasy emissary to hundreds of thousands of children in the small towns and villages west of the Mississippi River. Based in Queen Creek in central Arizona, Culpepper & Merriweather is one of the last of a fading class of circuses: one-tent, one-ring "mud" shows. It's very nearly like the tiny circuses that used to roll into country towns and villages in colorful hand-painted wagons, sometimes covered with mud from unpaved roads, more than a century ago. Mud shows aren't as glamorous and lucrative as Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey big-top productions, but, thanks to touring shows like Culpepper & Merriweather, they survive in a form that's darn close to the original. And, to many kids in the tiniest burgs across much of the nation, this is the circus the only one that comes to town. It has dazzling daredevil performers, scary-looking roustabouts, and strange trained animals. It has popcorn,

CIRCUS

pink cotton candy, and red-nosed clowns. It has beautiful women with long eyelashes and long legs in black fishnet stockings. You'd just know if you were a young kid in the audience that Culpepper & Merriweather is the kind of circus that still welcomes starry-eyed runaways. I hook up with the outfit in March at Coronado Middle School in Catalina, a community north of Tucson at the foot of the jagged black Santa Catalina Mountains. It's 8 P.M. on Friday, and a roaring thunderstorm looses its wet electric fury over the circus site.

I quickly duck into the grand blue and white striped tent and find the ring-master: Culpepper & Merriweather founder, owner, and fire-eater Robert "Red" Johnson. He's wearing a satiny turquoise tuxedo jacket with tails, a turquoise ruffled dandy shirt, black slacks, and a shiny black top hat.

"Jeez, when did you get here?" Red Johnson, 44 years old and nicknamed for his strawberry blond hair, has the look of a terrorized man. "You should have been here earlier."

He whispers, his eyes wide, scanning his audience. "The wind was terrible. We almost lost the tent. I couldn't believe it. It was like . . ."

Live organ music brightly pipes "There's No Business Like Show Business," and Johnson cuts off the story. He takes a near-by microphone, and the worried circus proprietor instantly becomes the beckoning charismatic ringmaster.

"Ladies and gentlemen, now in the ring, it's the magical, the beautiful, the talented Heidi and her Hollywood Dog Revue." After several more acts, the 90-minute show ends. Kids with big smiles squeal and laugh as they run ahead of their parents to cars and home and real life, splashing through each and every mud puddle along the way.

Johnson immediately directs his crew to tear down the show and pack up the tent. The plan is that we'll spend the night on the Coronado School grounds, get up at 5 A.M., and head caravan-style for the Army post at Fort Huachuca in southern Arizona. The circus is scheduled there for Saturday and Sunday, two afternoon shows each day. A percentage of proceeds is committed to a youth group on the post.

When I awake at 5:30, the circus is already compacted into its caravan of vehicles and heading off without me. I race apparently undetected by the cop in the patrol car and join them just as they turn off Ina onto Interstate 10 heading south. Wedged in the middle of the star-painted circus rigs, I'm part of a rolling parade. People drive by with big smiles, blasting their horns and waving at us like we're their friends or a cause they truly champion.

In two hours, nearly everyone in the circus performers, crew bosses, clowns, and roustabouts is racing to transform a bar-ren, soggy field across from the post's non-commissioned officers' club into a one-ring fantasyland. Most of the sounds of circus-making are drowned out by Johnson and a couple of hefty workers. They wield sledge-hammers and alternately strike and drive down steel tent stakes.

Children, their parents behind them holding them back, are lined up at the edge of the field watching this transformation. David “Stilts” Volponi, the circus’ 10-foot Uncle Sam, slowly ambles toward them. Quickly, wide-eyed toddlers move backward, brace themselves against mom and dad, and stare up at this could-be-a-monster thing.

Ringmaster Johnson, a lean man who runs several miles a day, pulls off his Phoenix Suns cap and wipes his brow. He's lamenting that his circus season begins in March, just as the NCAA basketball championships get under way, and the teams of the NBA head into divisional square-offs. As he talks, he watches the children watching a circus in the making.

“Like Groucho Marx said, ‘We started with nothing and worked our way up to a level of extreme debt.” He grins and puts his cap back on. Johnson, who “ran away” with Big John Strong's circus when he was 26, likes to joke that his circus went from four people and no money to 35 people and a lot of bills. “Yeah, you barely break even at this business, but that's never been the point. Remember that this isn't a show. What you see in the big cities are shows. This . . . .” His hand spans the field. “This is a culture. It's not a job. It's a way of life lived by a family of 35. My tent is put up the same way it was done 200 years ago. We use the same knots. We still use an elephant to pull up the big top. We're keeping alive a . . . .” isn't a show. What you see in the big cities are shows. This . . . .” His hand spans the field. “This is a culture. It's not a job. It's a way of life lived by a family of 35. My tent is put up the same way it was done 200 years ago. We use the same knots. We still use an elephant to pull up the big top. We're keeping alive a . . . .” The last of the convoy finally arrives from Catalina, and Johnson's off to meet them. To the kids at the edge of the field, these trucks carry the most important load: circus animals. Barbara the Elephant, the chief tentpole hoister, lumbers out of a trailer. There are the snappy little Liberty Ponies, miniature horses so named because they've never been ridden. There are a llama, trained doggies, Shetland ponies, and Mohammed, a club-footed camel Johnson and his office manager-mother, Theresa, rescued from an abusive home.

Johnson founded the circus in 1984 with three performers. At first the extent of the Culpepper & Merri-weather Great Combined Circus was a juggling and clown show that exclusively toured campgrounds and recreational-vehicle parks throughout the country. Money was made by the pass of a hat, hopefully enough to buy food and gas for the trip to the next stop.

Theresa, who books all shows and contracts with performers some from far away places like Guam and Budapest-recalls that her son eventually made enough money to buy a tent. Today two of the original crew are with Red Johnson: big B.J. Herbert, the tent boss, and aerialist Lynn Marie Jacobs. The circus season, which begins in March, lasts for eight months and usually includes more than 400 shows across much of the country. It's rare for Culpepper & Merriweather to stay in one town longer than 24 hours.

By noon, the blue striped tent tipped with Arizona and U.S. flags is up and billowing in a gentle wind cut by the Huachuca Mountains.

Inside is the circus' lone performance ring, formed by red and white curved wooden blocks, each with a backlit gold star. The roustabouts are outside the tent eat-ing at tables in front of the cook's trailer. Most of the circus performers are in their mobile homes and trailers, resting, dressing, and applying their glittery make-up. Kevin Ryan, also known as Kevin O'Clown Ryan, explains the major differences between a mud show like Culpepper & Merriweather and big three-ring circuses like Barnum & Bailey, known in the trade as "silk stocking" shows.

"Here, we're family," he says. "We all know each other, we get along, and everyone works together. In the big shows and I've worked in 'em you know names, but you really don't know each other. You don't eat together, and everyone's got their specific job, and that's all you do. Here we all have two or three jobs. Sure, I'm a performance artist, but if I can help with anything else, I do. Everyone does.

"The circuses like Culpepper & Merri-weather are dying out," Ryan says. "Just three years ago, there were at least 200 of them. Now it's down to 100 or probably less, and that's even counting the street-corner shows that call themselves circuses."

Ryan hails Tom Tomachek, an organist who, with drummer Dewey Welch, provides live music for the shows. They continue on about mud shows and silk stockings and their talk is hitched by unfamiliar terms that they explain.

"Blue skies" is when the circus comes to town without a sponsor. A "donniker" is a bathroom. A "butcher" is a vendor, probably so named because they used to hack off pieces of saltwater taffy. "Floss" is cotton candy, and a "larry" is damaged goods. An "Annie Oakley" is a free pass, and a "straw house" is a full house.

Then there's a "jackpot," says Ryan, who joined the circus in 1975. He tells me how he learned long ago what that term means. From a large family, Ryan loved the cir-cus as a child, and his love was encouraged by his father. Whenever the circus came to town, Ryan's dad would come home and tell him. Then he'd let Ryan skip school, and they'd go to the show, just the two of them. Their circus escapes were magical, Ryan recalls, and they made him feel especially loved by his father.

"It made me think my dad loved me most of all the kids and understood me best," Ryan says. "Then I found out years later that he did the same thing with my brothers and sisters. He knew the one thing we all liked most baseball, musicals, movies and he'd take us there, all by ourselves. All that time each of us thought we were the only ones Dad did this for." That's a jackpot, he says, when someone successfully pulls someone else's leg.

It's 1:30 P.M., half an hour to show time.

Aerialist Lynn Marie Jacobs is tending to her other duties in the spick-and-span concessions truck in which the last bin of sugar is spinning itself into a cloudy pink batch of cotton candy. Sugar specks sail out the snack-shop windows and turn into miniature stars as they catch the sun's reflection.

"Here, honey," Jacobs says, and she reach-es down and hands a little boy his soft drink and change. He runs off toward the tent, but she calls him back. "Why don't you put your change in your pocket so you don't lose it?" The boy jams dollar bills into his pants pocket and runs away.

It's 1:45 P.M. Performers are lining up outside the tent in front of a red curtain. As ringmaster Johnson announces their acts, the curtains will separate, and the performers will rush in on horses, with dogs, clownishly toting buckets and brooms, smiling all the while.

Lucius Setic, a wire walker from the Isle of Truk in Micronesia, performs as a clown, entertaining kids and selling colorful geegaws while the show gets under way. He eyes the tightrope wire above the crowd and watches the crew secure the lines. Setic's nephew, Oran, recently took to the wire and will be the featured walker this afternoon. Last year, Setic fell during a performance and crushed his leg. He doesn't know when he'll be able to return to the wire. Musicians Tomachek and Welch respectfully address the military families with a zippy rendition of "Over There." "Looks like a good crowd," Johnson says. "I hope we can . . . ."

It's show time. Johnson cuts off talk and takes up the microphone, introducing the first act. The red curtains part, and, sneaking a peak inside, I can't see anything underneath the dreamy blue Culpepper & Merriweather big top as bright and dazzling as the smiles on the youngsters in the audience. It's plain what they want, and it sure isn't bread. Author's Note: The one-ring Culpepper & Merriweather Great Combined Circus performs in Arizona in March. Its full season runs March through October. To inquire about its schedule, contact the circus at 2928 E. Ocotillo Road, Queen Creek, AZ 85242; (602) 987-3811. Marilyn Taylor was never tempted to run away with the circus, but at age 15 in California, she met her first serious boyfriend: a 19-year-old circus hand. Fred Griffin enjoyed photographing the circus performers, "the hardest working entertainers in the world."

Already a member? Login ».