When the Rains Came

I awoke in confusion, disoriented by a deep-throated growl somewhere off in the darkness. I stared at the stars shining fiery white overhead and the glowing swath of the Milky Way. The silhouettes of the saguaros reminded me that I'd laid out my sleeping bag in this desert wash hours before. Still, I couldn't place that grinding, grumbling growl, like a great stone lion clearing its throat before emitting a terrible roar. A distant jagged flash of light caught my eye, a lightning bolt off toward Four Peaks. I gazed toward that dark hole in the sky, uncomprehending, while the formless sound nearby grew in intensity. It seemed to be coming from everywhere and nowhere. As I strained to see in the starlit night, I realized that the sound came from up the wash, the same wash in which I was camped, lured to the sandy bottom by its thornless smooth surface. I peered up the wash in the darkness a moment longer before the clues connected as suddenly as a clap of thunder. Jumping out of my sleeping bag in my underwear, I grabbed my bag and my backpack and scrambled up the crumbling sides of the wash, cursing mightily as the invisible rocks scraped the skin off my toes, and the cactus thorns pierced my soles. Grasping the uncertain support of a scratchy paloverde branch, I pulled myself to the top of the bank, then turned to look back down into the wash at my pursuer. The leading edge of the flood advanced across the white sand, stretched from bank to bank, and swept everything along before it. The foot-high slurry of mud and debris rolled across my abandoned campsite swallowing my cooking kit, flashlight, and boots with a faint metallic gulp. Sitting ruefully in the warm dark, I listened to the gurgling of the water that makes it possible for the Sonoran Desert to thrive. I've seen raging floods devour bridges in the heart of desert cities. I've climbed the steep sides of the Inner Gorge of the Grand Canyon to stand beside a piece of floodborne driftwood left 50 feet above the river's surface. And in the course of a few days, I've seen a vast expanse of dry desert turned into a lake too long to swim. But I don't think I ever fully appreciated desert floods until that night spent sitting on the bank of a desert wash in my underwear, wondering where my boots had gone. Desert floods can wreak havoc, especially on fools who camp in washes during the monsoon season and developers who build houses in floodplains. Arizonans have rediscovered the lesson repeatedly in recent decades, including the winter of early 1993 when record amounts of runoff spilled from the reservoirs that supply Phoenix and raced down usually dry desert washes. Phoenix sits at the juncture of the Salt, Verde, and Gila rivers, which drain most of the state and parts of New Mexico, capturing the runoff from 50,000 square miles. Of course that's why Phoenix sits there in the first place. The earliest Indians discovered many centuries ago that these rivers made it possible to grow crops year-round in the Valley. Then there were the Hohokam who built hundreds of miles of irrigation canals in the 1400s before they abandoned the area. Some experts suggest that an outpouring like the winter of 1993 could have so devastated the laboriously constructed irrigation works that the Hohokam finally gave up and moved away. In fact archaeologists trying to reconstruct ancient patterns of rainfall and flood may have saved modern Phoenix. Experts from the University of Arizona's tree-ring laboratory used the width of tree rings in logs found in ancient pueblos, downed trees, and 800-year-old living trees to estimate runoff into Roosevelt Lake and discovered that the watershed could produce flows much

DELUGE IN THE DESERT BY PETER ALESHIRE

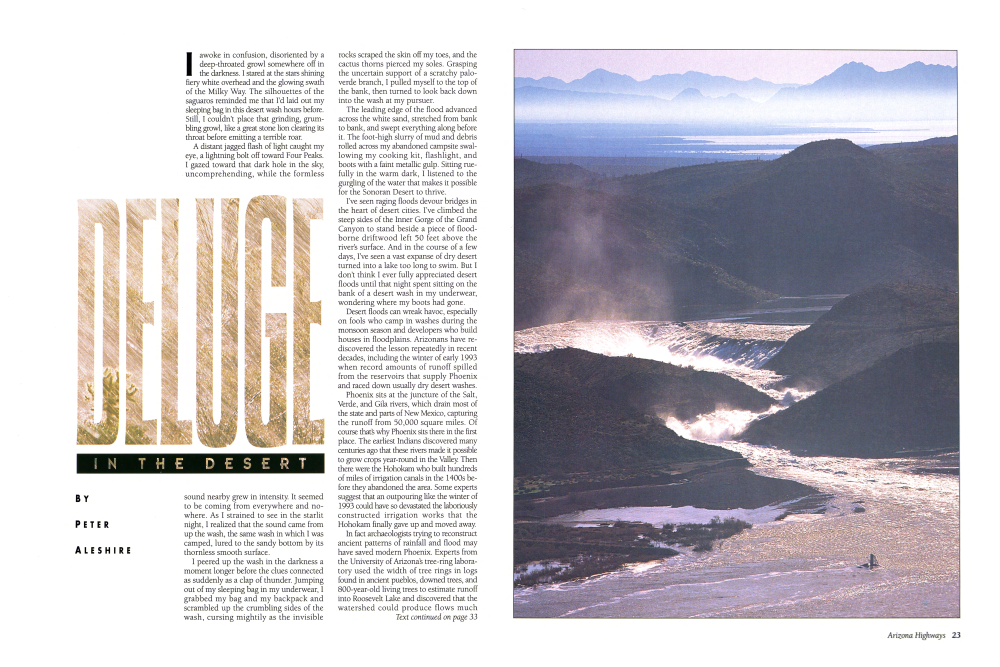

(PRECEDING PANELS, PAGE 23) Runoff from heavy rains spills over Painted Rock Dam near Gila Bend.

PETER ENSENBERGER (PAGES 24 AND 25) Willcox Playa, below the Dragoon Mountains, usually is dry, but heavy rains can transform it into a shallow lake.

JACK DYKINGA (LEFT) Tanque Verde Falls in the Rincon Mountains east of Tucson comes alive after monsoon rains. STEVE BRUNO

DELIGE

(PRECEDING PANEL, PAGES 28 AND 29) Snowmelt enlarges Sabino Creek in the Santa Catalina Mountains near Tucson. RANDY PRENTICE (RIGHT) Water from the runoff-swollen Painted Rock Reservoir backs up into the many washes that feed into the reservoir, creating the unusual sight of saguaro cacti standing in water. PETER ENSENBERGER

Continued from page 22 greater than the designers of Roosevelt Dam had estimated. That's one reason the federal government decided to spend millions to increase the height of the dam.

Despite the heavy investment in dams and flood-control projects in Phoenix and elsewhere, desert floods still inflict damage. The two-week succession of winter storms last year killed four people, damaged 600 homes, and caused $60 million in damages. Many areas of the state got a year's worth of rain in a matter of weeks.

The Salt River, which normally is dry through Phoenix, peaked at 124,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) as engineers opened the floodgates on a series of dams. The Painted Rock Reservoir downstream from Phoenix swelled to 2 million acre feet, more than twice the size of Roosevelt Lake. The water topped the reservoir's spillway for the first time in history, sending up to 50,000 cfs rushing down the Gila River toward Yuma, inundating thousands of acres of farmland.

Even so, other floods have carried more water and done more damage. Back in 1891, 300,000 cfs rushed down the Salt River, prompting the terrified settlers to lobby the federal government for floodcontrol works on the Salt and Verde rivers. Since 1978 major storms have inflicted more than $177 million in damages on the Valley where the Hohokam laid out their canal system a millennium ago.

Floods can occur in both winter and summer. The biggest floods statewide hit in the winter, when a capricious jet stream can steer huge storm fronts from the Pacific across California and into Arizona. These storms account for perhaps two-thirds of the annual rainfall in Arizona, which averages about seven inches a year in low-lying areas like Phoenix. Numerous plants and animals rely on these winter storms, and even the floods they sometimes produce. Many desert streams and rivers flow only when there is flooding.

Because most desert creatures depend to some degree on these riparian areas, the flow of water through these desert washes controls the whole ecosystem. For instance, the cottonwoods and willows that provide one of the most wildlife-rich ecosystems in North America rely heavily on floods to seed. Biologists were delighted to note cottonwood sprouts all along the Gila River last summer, the ecological silver lining to the winter's damaging floods.

Weather patterns reverse themselves in the summer, when the jet stream dumps storms on Alaska and Canada. Fortunately for the Sonoran Desert, just when life begins to wilt with summer heat, water-laden air rising off the sweltering oceans of the tropics swirls inland and unleashes fierce monsoon storms, making possible the rich diversity of plants and animals in the desert regions of Arizona.

The entire desert ecosystem pulses to the beat of the August monsoons. Many plants flower in the spring but wait to set their fruit and disperse their seeds until the balm of the monsoons. Fleshy water hoarders like the saguaro drink through shallow root systems that fan out 50 to 100 feet.

The insects that live on the pollen of these plants likewise adjust their life cycles to the summer rains. Solitary desert bees subsist on the nectar gathered during the spring and again in the late summer, when many desert plants flower in response to the monsoons.

Desert ants and termites take wing after monsoons, racing to mate in midair and - in that precious span of hours when the ground remains moist and diggable excavate a hole that will shelter a new colony.

An array of desert toads and frogs lies virtually mummified in underground burrows, awaiting the low-frequency drumming of the summer rains. They emerge, mate, lay eggs in the temporary water pools, then return to their burrows. They leave their tadpoles to rush through a compressed development, those that grow fastest often eating the late-comers in the shrinking desert pools.

So it goes throughout the ecosystem, as each plant and animal adapts to the cycles of flood and drought.

That's why it's hard to regret rain in arid lands, even when it swallows your boots in the middle of a cactus-studded desert.

I half dozed through the long hours until daylight. The frogs started their crooning sometime during the night, summoned from their long slow dreams by the smell of water.

The stream had already dwindled to a trickle by dawn, catching the reflection of saguaros in pools scattered across the wash bottom. A few natural rocky cisterns harbored shallow pools where I knew the frogs would lay their eggs before leaving their offspring to swim their frantic race with desiccation.

I sat bathed in dawn light on the hillside and blessed the desert rain - and the people who'd made my new boots so uncomfortable. This trip I'd taken the unusual step of packing a backup pair of tennis shoes, now nestled snugly in my pack. Cheered by the thought, I watched the sun rise across the gleaming wash as the clouds massed above Four Peaks, half hoping they would move my way and refresh my memory of the smell of the desert after a monsoon rain.

Already a member? Login ».